The Los Angeles Synagogue Attack Wasn’t a Warning for Jews Alone

Christian communities must take heed

RINGO CHIU/AFP via Getty Images

RINGO CHIU/AFP via Getty Images

RINGO CHIU/AFP via Getty Images

RINGO CHIU/AFP via Getty Images

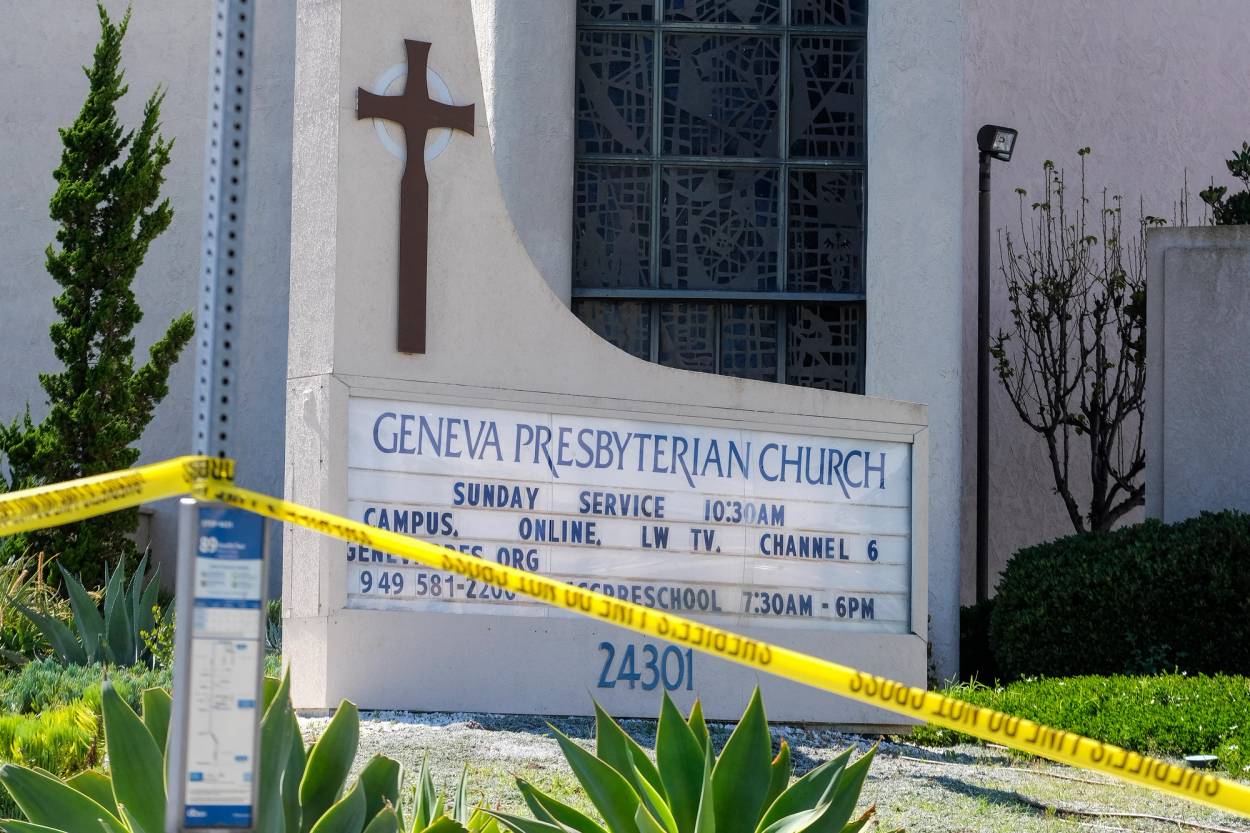

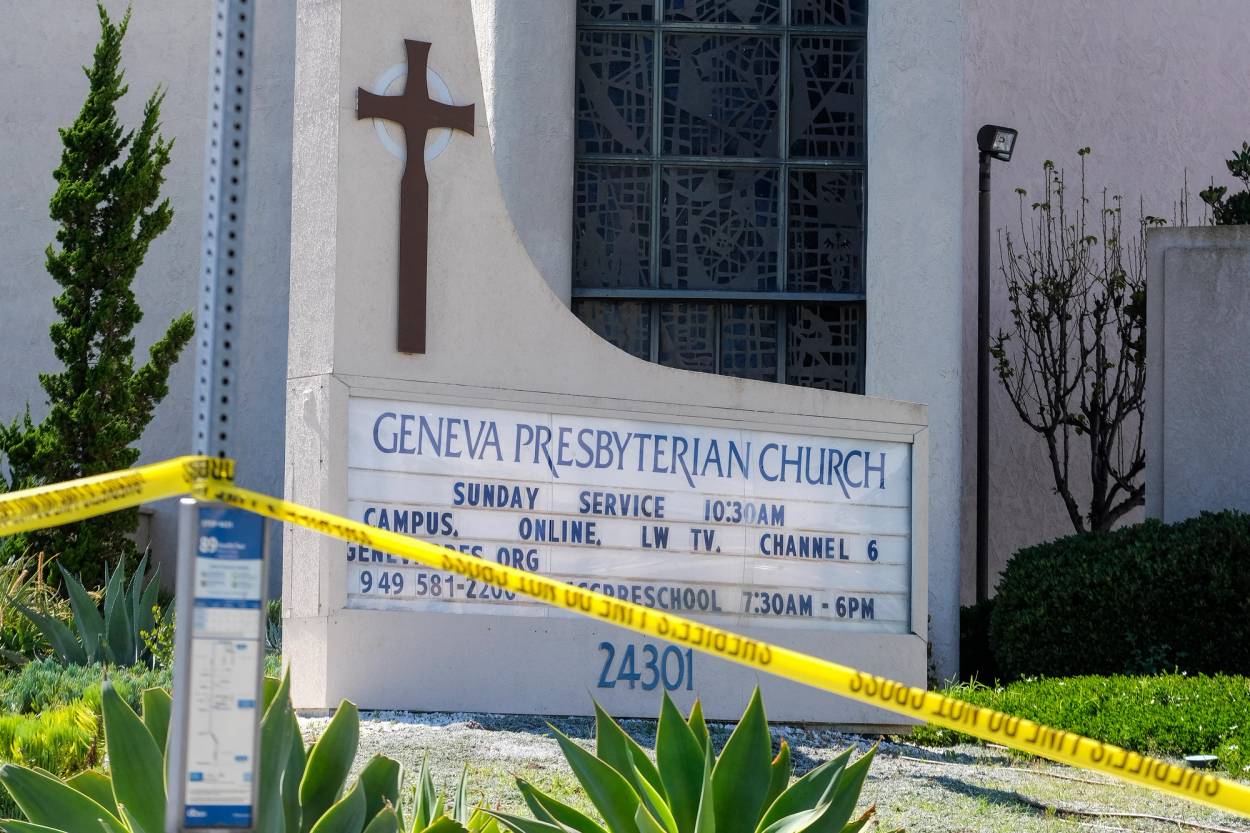

A violent mob organized by a movement that sympathizes with the Marxist terrorist group the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) descended on a Los Angeles synagogue on June 23, intent on intimidating worshippers. Masked and keffiyeh-clad goons maced and pepper-sprayed members of the local community while police—reportedly instructed not to intervene by city officials—looked on.

This pro-Palestinian terrorism pogrom outside the Congregation Adas Torah Synagogue was orchestrated in part by the Palestinian Youth Movement. It was aimed not at political opponents, but at a whole community, specifically the Jewish community of the Pico-Robertson area of Los Angeles, one of the country’s largest and most influential Jewish neighborhoods.

While the role of Islamic and far-left antisemitism in motivating the attack is obvious, it is not immediately clear why Jewish communities in the United States should be so vulnerable. In theory, the American Jewish community should be more secure and more resilient to such threats than nearly any other religious or ethnic community in this country.

To begin with, the Jewish community has never been oblivious to the threat of violent antisemitism and has long taken steps to address the problem. Numerous community organizations exist to advocate for and provide security to Jewish institutions. Historically, Jewish institutions have received the majority of Department of Homeland Security funding through the Nonprofit Security Grants Program. Organizations like the Secure Community Network (SCN) provide education, training, and alerts to Jewish institutions on a variety of threats.

As SCN’s Brad Orsini has noted, the “days are gone where we can rely on law enforcement solely. … We can no longer afford to have security as a luxury. It needs to be a line item budget in all our facilities.” The West Coast-based Magen Am provides armed rapid response support and does guard service for multiple synagogues, Jewish schools, and community events in three cities, including Los Angeles. Private first responder networks, known as Hatzalah, provide ambulance and EMT capabilities in many Orthodox Jewish communities.

Behind this laudable understanding of the security challenges stand larger community organizations with multimillion-dollar budgets that—at least theoretically—possess not only the political and reputational heft to engage with civic leaders and law enforcement and demand action and accountability, but also the legal acumen to seek civil causes of action against the groups and people who target their communities.

And this is all for the good.

But, for journalist Daniel Greenfield, the assault on Pico-Robertson represents “a moral and strategic failure” of Jewish community leadership that left neighborhood residents, synagogue attendees, and Jewish counterprotesters fundamentally unprepared to meet the assault.

Jonathan Greenberg, a Reform rabbi active in Jewish philanthropy, notes that such failures are as much about mindset as the availability of assets. He writes, “A key takeaway from the last several months and the Jewish community had better learn it right quick: We need to harden our targets right now. And it starts with hardening our people.”

The number of attacks targeting Christians are dwarfed by attacks on Jews. But the point here is not to compare injuries, but rather to point out that both communities find themselves confronting the same or similar threats.

Part of that hardening is the necessary recognition of the change in American Jews’ status in the progressive stack. For decades, the country’s Jewish community was seen as a vulnerable minority; it enjoyed the protection of the extensive civil rights legal apparatus adapted to focus on the rights of perceived vulnerable communities. Increasingly, this is no longer the case. Jewish Americans have found themselves lumped—by academics, campus radicals, and the elites—among the oppressor rather than oppressed class.

That perceived oppressor class, white American Christians—which once made up the overwhelming majority of the population of the United States—has already become a statistical minority. American Christians, of all ethnicities, are expected to drop to a minority of the population within the next few decades, as well.

According to the Family Research Council, between 2018 and 2022, there were 420 incidents of violence or vandalism targeting Christian churches. The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops tabulate more than 333 incidents of arson, vandalism, or other destruction targeting Catholic Churches between 2020 and 2022. This does not include attacks on pro-life organizations and pregnancy resources centers, often operated as Christian ministries, which came under targeted assault by the pro-abortion anarchist group Jane’s Revenge following the Dobbs decision.

As with attacks on Jewish communities, these trends are even worse abroad; they are an unfortunate lagging indicator of where the United States is headed. In Europe, anti-Christian hate crimes, including arson and physical attacks on Christian communities, rose 44 percent in 2023. In Canada, inspired by a series of false news reports regarding the presence of “mass indigenous graves” on Canadian church properties, more than 100 arson or vandalism attacks took place.

The number of attacks targeting Christians is dwarfed by attacks on Jews in America, of course, but the point here is not to compare injuries, but to point out that both communities find themselves confronting the same or similar threats.

And, as with the attack on the Pico-Robertson Jewish community, there is an apparent resistance by some government authorities to provide protection, bring to justice perpetrators, or even admit the extent of the problem. Republican lawmakers lament the Department of Justice’s inaction in responding to attacks on Christian churches and other institutions; nonprofits are forced to sue the DOJ, alleging the department is hiding information about church attacks; and prosecutors have repeatedly sought lesser or no penalties for perpetrators targeting Christians. Meanwhile, the Justice Department authorizes domestic spying operations against American churchgoers for alleged extremism, and mainstream media outlets have taken to labeling basic tenets of the American Founding as “Christian Nationalism.”

If, as Greenfield and Greenberg warn, a cultural memory of being a vulnerable minority as well as decades of institutional effort are insufficient to mentally or physically harden the American Jewish community to resist such threats, how vulnerable are the American Christian communities that find themselves in the same boat? While Jewish communities clearly need to do more work to secure their communities amid growing challenges, American Christians can and should apply lessons from the Jewish community approach.

First and foremost, the task for American Christians begins by regarding themselves as real communities. This can happen geographically, as discussed by writers like Rod Dreher in The Benedict Option. But, primarily, a community identity is forged through the creation of institutions that can represent its common interests to civic and business leaders. No common interest is greater than security.

There are resources, in the public and private sectors, on creating “church security teams.” Some of these are of questionable value; others have been developed by genuine experts. But there is no Christian example of important efforts like the SCN, which helps coordinate security for the Jewish community by developing best practices, sharing threat information, and providing assistance in applying for grants to institutions with security concerns. Just as important is having a broader network of media, political, legal, and cultural support for the community, in case a church were to face a threatening situation similar to the assault on Congregation Adas Torah.

There is a common threat often uttered by Islamists in the Middle East, many of whom have been imported not only to the streets of Los Angeles but to your town as well: “First the Saturday people, than the Sunday people.” There is much the Sunday people could learn from their Jewish counterparts about protecting their communities, and now is the time to get serious about learning it.

Kyle Shideler is Director for Homeland Security and Counterterrorism at the Center for Security Policy.