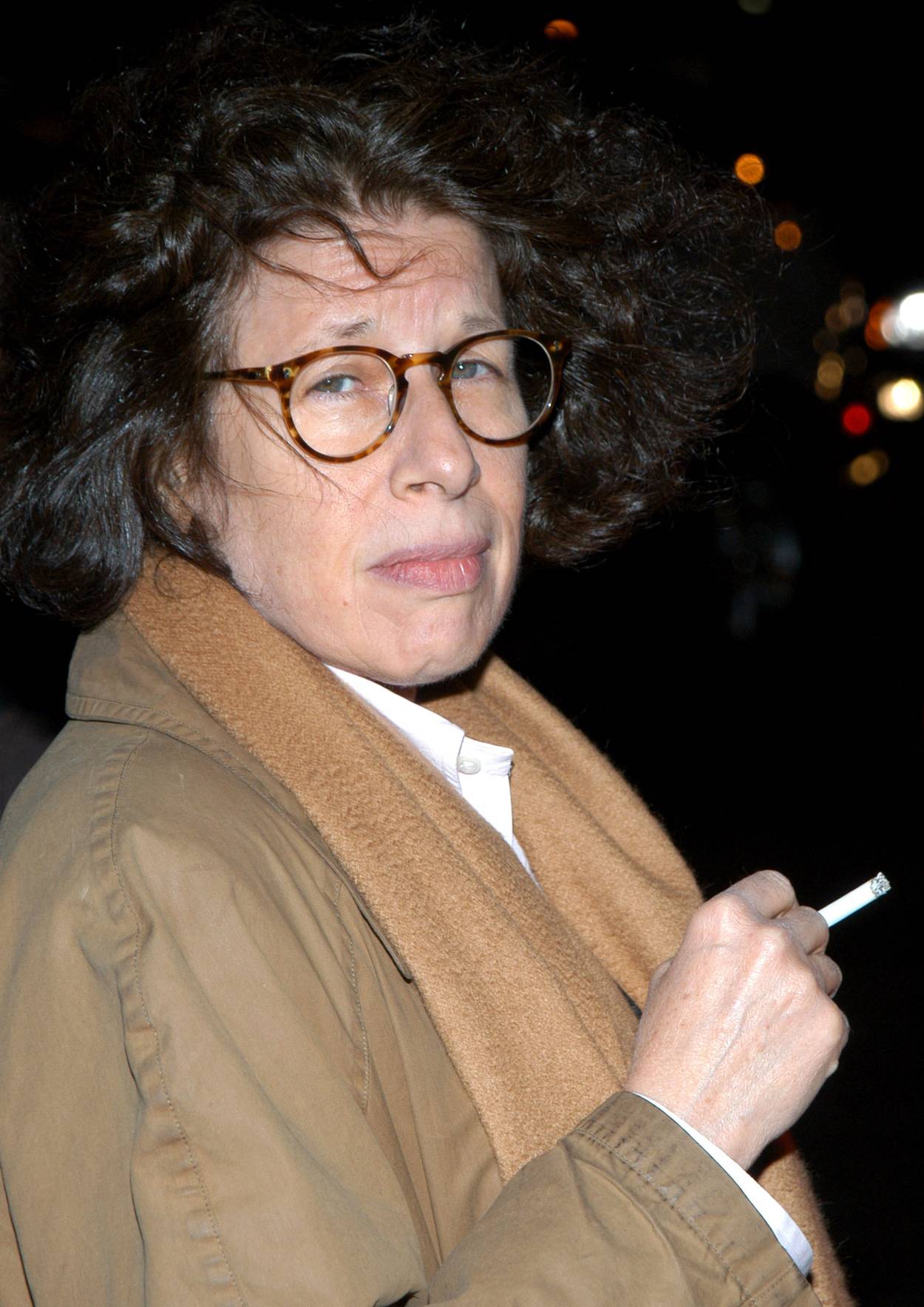

Fran Lebowitz Wasn’t Kidding

The avant-garde Jewish lesbian essayist was a forerunner of petty 1990s observational comedy. But she is also something deeper.

Stephen Lovekin/FilmMagic

Stephen Lovekin/FilmMagic

Stephen Lovekin/FilmMagic

Stephen Lovekin/FilmMagic

“Far be it from me to make noise while you’re asleep but I should like to notify you that you are under arrest for being boring.” Midway through one of the best—funniest, most troubling—essays in her first book, Metropolitan Life (1978), Fran Lebowitz turns on her reader. The flash of sudden hostility is too campily deadpan in its bureaucratic politesse to give real, or at least immediate, offense. It cannot be mistaken for the rude and noisy grimaces of comedians like Andy Kaufman and Sam Kinison, populist inheritors of the avant-garde artist’s open contempt for his bourgeois patrons. She must be kidding.

As Lebowitz continues, we find ourselves further reassured. We are, it turns out, suspected only of such possible crimes as talking about our therapists or having an excessive interest “in the private lives of deservedly unknown homosexuals”—mild ordinary infractions against good conversation that anyone (at a cocktail party in 1970s New York) might commit. The principal charge—you are boring—disappears behind a particulate fog of small annoyances, grist for comedic mills of a later generation of “funny” men with exaggerated grievances (“airline food—ugh!”).

Much of the humor in Metropolitan Life and its sequel Social Studies (1981) does take this unfortunate form, railing with eye-popping intensity against such dimly remembered momentary irritants as mood rings and wall-to-wall carpeting. Critics and the public greeted this carping with near-universal enthusiasm. In a profile of Lebowitz timed to promote Social Studies, New York magazine raved that it was stronger than her first book, letting us know from the get-go that “Fran hates everyone and everything.”

Her small targets add up, apparently, to a sweeping and easily relatable attack on “civilization” and “humanity as we know it.” Raging at a million peccadillos, apparently, she covers the whole human race in equal contempt—so no one in particular should get too rattled by her jokes. Or indeed recall that she called us boring. But really, the joke is on you.

Middlebrow dullards are suspiciously comfortable with the idea that everyone is morally deficient and that everyone is being criticized by their preferred comedian or prophet. It’s preferable to be told that we’re all born guilty than to hear that you specifically are boring. Thus the enduring appeal of Christianity and its secular successor, socialism—religions that tell us everyone is a helplessly wretched failure needing permanent care from a class of spiritual-political nursemaids, while excusing us from the difficult pleasure of being an interesting person.

Witness Daniel Bessner prematurely eulogizing Larry David, who could be seen as one of Lebowitz’s successors as Petty Complainer-in-Chief:

David is not alone in his ability to offend. But his propensity to do so emerges from a profound humanism—an egalitarian humanism inherent in the best Jewish comedy. For David, every person, from the pauper to the king, is fallen and thus open to mockery. This includes Holocaust survivors, hurricane and natural-catastrophe victims, the working class, and, of course, Jews. David’s work is premised on the notion that all people can be—just as he is—weak-willed, striving, awkward, prone to vanity, and frightened. Life is awful, and so, David insists, why not have a good laugh about it?

Well, for one, life’s not awful if you’re hot. It’s not even awful if you’re smart, which isn’t as good as hot but which, like most things that aren’t as good, lasts longer. Actually, statements about life are bullshit, since each of us has just one life to generalize about. And if your life is awful, Daniel Bessner, why not change it? Perhaps you need help. You’re under arrest for having an awful life.

Lebowitz’s attack on her boring audience comes midway through her brilliant essay “The Right of Eminent Domain Versus the Rightful Dominion of the Eminent.” As the second half of the title reminds us, there are, obviously, some people who are better than others. In our everyday talk we tend to forget this, since we live in a political regime that, as she says elsewhere, has at its principal flaw a “regrettable tendency to encourage people in the belief that all men are equal.” In fact, “although the vast majority need only take a quick look around the room to see that this is hardly the case, a great many remain utterly convinced.”

“Better,” for Lebowitz, doesn’t not mean more virtuous or even smarter. While critics of democracy from ancient Athens to right-wing Twitter today have seethed that the ignorant envious multitudes hold back the rule of the strong, excellent, and mysteriously ineffectual would-be tyrants, Lebowitz—who frequently joked about wishing to be “dictator” or “Pope”—sets the terms of preeminence—that is, of inequality—elsewhere. There are three questions that are of “greatest concern,” she insists:

(It’s under the second heading, by the way, that you’re under arrest for being boring. You do not amuse.)

The first two points are joined in a larger category we might call the “interesting,” keeping in mind other people’s sad habit of saying “oh that’s interesting” when they mean the opposite. Lebowitz does not demand the arrest of the boring because they’ve failed to attend to the really important things like piety (ugh) or high culture (snore)—religion and art appear in her work only as subjects of jokes. The attractive and amusing are the qualities of charming guests and lovers, not of the literary canon, much less canon law. As she reminds us elsewhere, “when dealing with a concept such as important one would be well-advised to ask, ‘to whom?’ … probably not us.”

The important is of no concern—what matters is being interesting, pleasant, and funny, the qualities that make life, for those who have them and those in their proximity, not awful. Meanwhile, the interesting, as a category, applies only among us, among some scene of shared taste. The public, “is not a particularly interesting group,” since by its very nature it is concerned with things that involve everyone and thus do not concern specifically our sort.

Whatever makes us laugh is also calling us to judge, to discriminate, to remember that some things are funny and some aren’t, that some experiences are bleakly tedious and others ecstatically vitalizing, that some people are capable of breaking us even against our will into frantic delight, while others stammer fretfully and annoyingly on stage. A comedian at her best is said to be killing her audience in part because there is always something overwhelming, surprising, wrenching about being subjected to the excellence of any artist, and perhaps particularly one who forces out of our body spasms of laughter.

As the above description suggests, there is something violent and tyrannical about the comic, the comedian. Although she often expressed her wish to be absolute empress, Lebowitz—like that other New York Jewish lesbian intellectual with a superiority complex, Susan Sontag—begrudgingly accepted liberal democracy, but only against her own temptations to sweep away the ugly and stupid in a great police round-up. Consider, after all, democracy’s competition. Brezhnev-era communism “is too dull,” and you can’t get a decent linguine, let alone a profitable book deal, on the collective farm. Fascism, on the other hand, “is too exciting.” Both demand a lot of group activities, like mass calisthenics and genocide. Neither have much need for writers specializing in “amusing fictions.”

And while democracy does give people the mistaken idea that they might be as good—that is, as attractive and amusing—as others, when they are so clearly not, it does have, besides its material comforts and relative lack of political stridency (two items ever less evident in recent years, it must be said), our wonderful “division between the public sector and the private sector.” We can keep our dictatorial impulses (as ideally, other people will keep their stupid opinions) safely in the latter, letting them out in public only in the benign, scarcely recognizable form of the humorous essay.

Many of Lebowitz’s essays, collected in the Fran Lebowitz Reader, are no longer, or were never, so humorous. Her gripes about the neologism “SoHo,” loft apartments, and conceptual art fail to rise out of the private domain of the merely whiney and would-be dictatorial (“I hate this!”), insufficiently disguised by wit and style. Paradoxically, it is only through a feat of utter superiority to the public, masterfully forcing it to laugh, to enjoy, to pay attention, that the artist convinces gains for herself the right to air aloud, without bursting their egalitarian delusions, her personal grievances against the multitude.

Some of her writing, however, came closer to fiction, proper narratives rather than first-personal complaints, of which a few remain worth reading. Most are simple, flat transpositions of one situation onto another, in the mode of a hacky improv comic running through her stack of mental madlibs (“hey guys what if [Celebrity] had to work as a [Profession]? I think it’d go a little something like this …”)—or the dudes at podcasts like CumTown shooting the shit. Like, haha, hear me out, what if the new pope were a California airhead (“At Home with Pope Ron”)? These stories knock the unsuspecting premise to the ground, kick it to death, and keep kicking.

“Breeding Will Tell: A Family Treatment,” imagines Lebowitz recounting her grandmother’s Eastern European childhood to her blue blood WASP friends, transforming Nana’s poverty and Cossack-dodging into an aristocratic picaresque. It starts with grim whimsy—she was born in “Ghetto Point, Hungary (a restricted community)”—that might have opened into a fantastic narrative in which the horrors of old Europe are hilariously inverted (and thus, ironically, made freshly terrible for us) seen through the funhouse mirror of petty everyday snobbery, with something of the humor of Candide traipsing hopefully through the disasters of 18th-century autocracy and imperialism. Instead, we’re tortured with puns (“her dance pogrom was invariably full”).

The collision between dark fantasies about the miserable old-country past and social aspirations for the present was a gold mine for other Jewish comedians—Woody Allen transforming into a Hasidic stereotype in the eyes of Annie Hall’s family, or Jerry Seinfeld yelling at his mother’s second cousin, “You had a pony!?”—but Lebowitz is unable to do as much with the material. First, because, as too often, she’s content to restate the premise several times without actually doing anything funny with it (call it Saturday Night Live fever). Second, because anything touching on family, Jewishness, the personal (say, her own lesbianism) seems to strike her as alarmingly close to unfunny sincerity.

Lebowitz starts having—and creating—real fun, however, in stories like “The Family Affair: A Moral Tale,” which imagines that heterosexuals, bored with reproducing the natural way (and who wouldn’t be?) begin cruising for the bars for children:

the most aggressive were known to sidle right up to promising-looking tots and murmur, “Like to play catch, fella? ... The backroom was reserved for those with more specialized tastes. Here the toddlers would leave one of their overall suspenders unbuttoned to indicate their special preference. An unbuttoned left suspender meant: I talk back … I don’t do my homework … An buttoned right suspender meant: It was my fault … I’ll try to do better … This gang inevitably found their way to the adults carrying their cigarettes in their left hands, which meant: No dessert … Go to your room … I threw them away … We don’t have Christmas.

Here the transpositions are genuinely comic, in part because there is more than one at play. Straight couples flirt with babies instead of each other. They act like (male) homosexuals—with a parody of the then-popular hanky code. Children and parents are well or poorly behaved only as moves within a mutually consented to sado-masochistic game—and being Jewish, at least if you’re a parent, is sadistic. The reference to Jewish family life and Lebowitz’s resentments about her own is funny because unexpected, coming as the last screw in a series of turnings inside-out of sexual and familial order.

Indeed, what Lebowitz is best at bringing to life, besides the barely suppressed violence of the democratic dandy who must turn his dictatorial desires into public clownery, is the strangeness of belonging to a particular group with its own codes and rites that must look absurd not only to outsiders but to even the insiders in their moments of temporary estrangement (which come over the best of us, in our hangovers and dry spells). That is to say, if she mocks and assaults the public, for the sake of what’s interesting to us, she is no less concerned to mock, more lovingly, than us.

In a September 1981 issue of Interview, John Waters asked Lebowitz why she made so many Catholic jokes (“Pope Ron”), since she hadn’t, after all, grown up Catholic. “Because it’s so funny,” she laconically responded. Trying to get more out of her, Waters pressed, “I think it’s great to have a Jewish writer, they always write about Jewish things but you don’t, you write about Catholic things.” His fumbling concession that “it’s great” to have a Jewish writer who writes about Jewish things accidentally echoes one of Lebowitz’s essays in which a well-meaning gentile teacher, speaking of Easter eggs to her elementary school students, stops herself to remind them that “the Jewish children in the class … I’m sure have something just as nice on their holiday, which is called Hanukkah.”

Maybe, Waters went on, what appealed to her about the topic of Catholicism was the “guilt,” so similar to Jewish guilt. Waters’ own films, at least before he traded in shock-schlock for the feel-good fun of Hairspray, trade in disgusting, horrific, and, depending on your taste (not mine), hilarious attacks on all proprieties, with the energy of a 2-year-old refusing to be toilet trained. So perhaps, in his case, giving the finger to the Catholic trinity of Mom, Dad, and God really was at the bottom of his art. Lebowitz, however, evinced a sense neither of personal guilt nor of a Judeo-Christian moral continuum on the subject, answering, “Jews don’t really have guilt about sex the way Catholic people do. Jews, they never mention sex, so you don’t have to feel guilty about it.”

And indeed, when sex appears in Lebowitz’s essays it’s as something faintly ridiculous, likely to lead people—especially others, especially gay men—into regrettable situations with the stupid and beautiful. See her “Notes on ‘Trick’” (laid out in a series of faux-serious numbered fragments in a send-up on Sontag’s more famous, and infinitely more tedious, dive into gay male culture), i.e., a casual sexual partner who is, Lebowitz warns, only too likely to stick around and try to express his “innermost thoughts” like a real person. Sex produces other complicating entanglements, such as children (with their sticky hands and frustrating inability to smoke), but it’s hardly worth feeling guilty about.

Finally giving in and offering a serious answer, Lebowitz explains to Waters:

I think the reason I wrote about Catholicism is that it’s really a perfect subject for a humorist because it’s so strict. The reason there hasn’t been any great American comic novels for a long time, the way there are great English comic novels, is because there’s no class system here. Someone who is a humorist or a satirist really needs something to work against and the Catholic church is perfect for that. In order to make fun of something you have to have something concrete to make fun against. The Catholic church offers a perfect opportunity for any satirist who cares to tackle it.

But far more than the Catholic Church, Lebowitz’s substitute for a “class system” was the world of gay men in 1970s New York—a world, like the Church, with distinct rules, roles, sites, and sensibilities. Ineptly parodied in Edmund White’s first novel, Forgetting Elena (1973), which imagines the Fire Island scene as a baroquely coded, mysterious subculture through the eyes of an amnesiac anthropologist, gay male life was, and has continued to be, a fascinating subject for a certain kind of lesbian—Lebowitz, Sontag, Sandra Bernhard doing Sylvester, Judith Butler on Paris Is Burning—understandably bored by the relative unliveliness of (if the term isn’t a simple oxymoron) lesbian culture.

Lebowitz is best at bringing to life the strangeness of belonging to a particular group with its own codes that look absurd not only to outsiders but to the insiders as well.

Many of Lebowitz’s best essays and stories, like “Family Affair” and “Notes on ‘Trick’” draw on the concrete, objectively funny arrangements of gay life (can anyone watch Al Pacino sniffing poppers in Cruising without laughing?) to give herself not only material to work with, but also an attitude and an audience—an us—to appeal to. “Class,” after all, is not only a system to be satirized, but also a system within which one has a place. As she put it in her inimitable defense of smoking, “I use the word ‘class’ in its narrower sense to refer to that group more commonly thought of as ‘my kind of people.’” American democracy certainly doesn’t lack for brutal economic inequalities, but so many Americans apparently do not have, or do not like, their own kind of people, and cast instead about for pitiful universalisms founded on the “fact” (true in their own cases, false in mine and hopefully, reader, yours) that life sucks.

In seeing the gay male world of pre-AIDS New York as a model for how to be the right kind of us—a minority large enough to sustain a commitment to the attractive and amusing, without becoming self-important or trying to reform a necessarily ineducable public— Lebowitz was following, while improving on, Sontag. In “Notes on Camp” the latter had argued that in our democratic culture, which has no hereditary aristocracy (according to a woman who grew up lower middle class in the Sunbelt, though I assure you there are rich old families in Massachusetts and Virginia who could give the Hapsburgs a run for their money, inbreeding-wise), depends for the possibility of maintaining the aristocratic spirit on the willful posturing of self-conscious minorities like male homosexuals.

Apparently gays’ peculiar enthusiasms (in Sontag’s day, Aubrey Beardsley and Tiffany lamps—which frankly sounds rather tame and grandmotherly even for 1963) are a kind of mental resource by which they manage—and thus inspire others—to style themselves as aesthetes who neither endorse the “serious” values of the antiquated “high culture” (for Sontag, this includes such bores as “The Art of the Fugue,” along with “Jesus” and “Napoleon”) nor call for revolutionary avant-garde art to clear the way for a new world. Rather, these more “refined” aesthetes appreciate what is around them, the wrecks of tradition and modernity, high and low culture, with a specially cultivated “unnatural” attitude that permits them to find a peculiar, rarefied pleasure in apparent disasters (more recently, think Showgirls, think Marianne Williamson at the Democratic primary debate, think anyone incandescently unaware that they’re doing a terrible job). As Lebowitz put it, “Where the heterosexual feels a sense of duty, a sense of honor, a sense of responsibility, the homosexual feels a sense of humor, a sense of protocol, and most significantly, a sense of design.”

Which is not nothing, especially in our otherwise flat and desolate national life, in constant peril of becoming a wasteland where occasional glints of Masterpiece Theater "art” shine boringly amid culture-industry sludge (Martin Scorsese’s newest self-important snoozer vs. the latest Marvel abomination). In neither case is there anything like taste, that is, a genuine aesthetic response that is not merely signing on to received opinions (every contribution by supposedly intelligent people to Taylor Swift discourse, for example, reads like Havel’s greengrocer putting a “Workers of the World Unite!” poster in his window) or a lighting-up of the animal parts of the brains. Luckily camp—that is, the male homosexual—models the possibility of enjoying what is available in a way that is one’s own, precisely because one shares it with other members of a community of oblique enjoyers.

Now it must be admitted, as Lebowitz observed in the 1970s, gays have inflicted on the world such catastrophes as A Chorus Line and “leather underwear.” Their (our) taste can hardly be depended on. Indeed, taken seriously the idea that gay men’s aesthetic sensibility can escape the double dangers of tedious “important” humanist sermonizing and pop-timistic post-critical enjoyment proves desperately flimsy. It rhymes, in its touching inadequacy, with art critic Dave Hickey’s hopes for Americans’ democratic enthusiasms for high and low culture, or with Hannah Arendt’s insistence that the faculty of aesthetic judgment could exemplify the virtues needed for an authentic life and decent politics. There is something, however, urgently right about these diverse thinkers’ common intuition that having good taste—a mode of appreciation that is both authentically one’s own and communicable within the circuit of like-minded pleasure-seekers—is the basis of a good life, which is what liberal democracy in its characteristic division of private and public is meant to defend.

The good life—a life of something more than consuming indifferently prepared commodities or following conventions, of being good, polite, or important—is a life at odds with the common good of the public. But it is a life in an us, among friends whom we make fun of and to whom we make fun of others—the audience to whom we want to be attractive and amusing, and with whom we are in our place.

Lebowitz most clearly expressed her sense of the importance of this us in one of her rare writings published after 1981—the year when Social Studies was published and the AIDS crisis began. Asked by The New York Times in 1987 to comment on how the crisis was affecting the “artistic community,” she answered in twelve fragments, some joking, some somber. The seventh read:

The Impact of AIDS on the Artistic Community is that a 36-year-old writer takes time out at a memorial service for the world’s pre-eminent makeup artist and a man worth any number of interesting new painters to get angry because the makeup artist’s best friend and eulogist uses a story that she has for years been hoarding for her book which she can’t write anymore anyway unless she writes it as a historical novel because it’s about a world that in the last few years has disappeared almost entirely.

The world in which we can have something other than the awful life that everyone has, a beautiful life of our own, shared with our sort of people, is perishable, and always perishing. For this reason, the would-be dictator, the aesthete, who apparently scoffs hatefully at “everyone and everything,” has more than anyone else—far more than the sad-sack “egalitarian humanist”—a love of the world, which is after all not the objective, boring planet Earth, or the unknowable and therefore uniform public, but the place where we meet our specific, mortal friends. Friendship, like comedy, like any excellence, reminds us that some people are to be cherished above others, that we are, if ever, cute, brilliant, and funny with and for them.

Blake Smith, a contributing writer at Tablet, lives in Chicago.