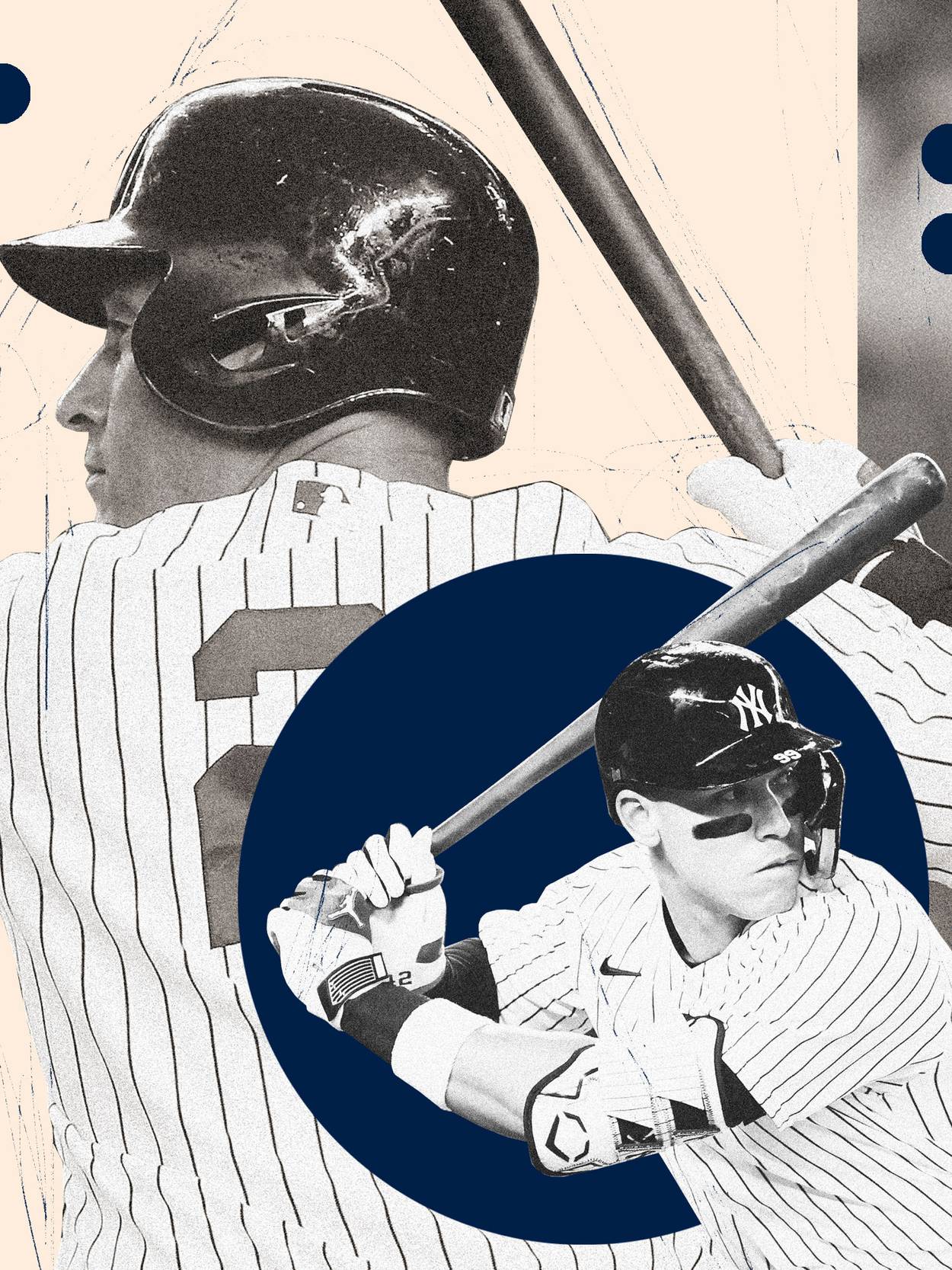

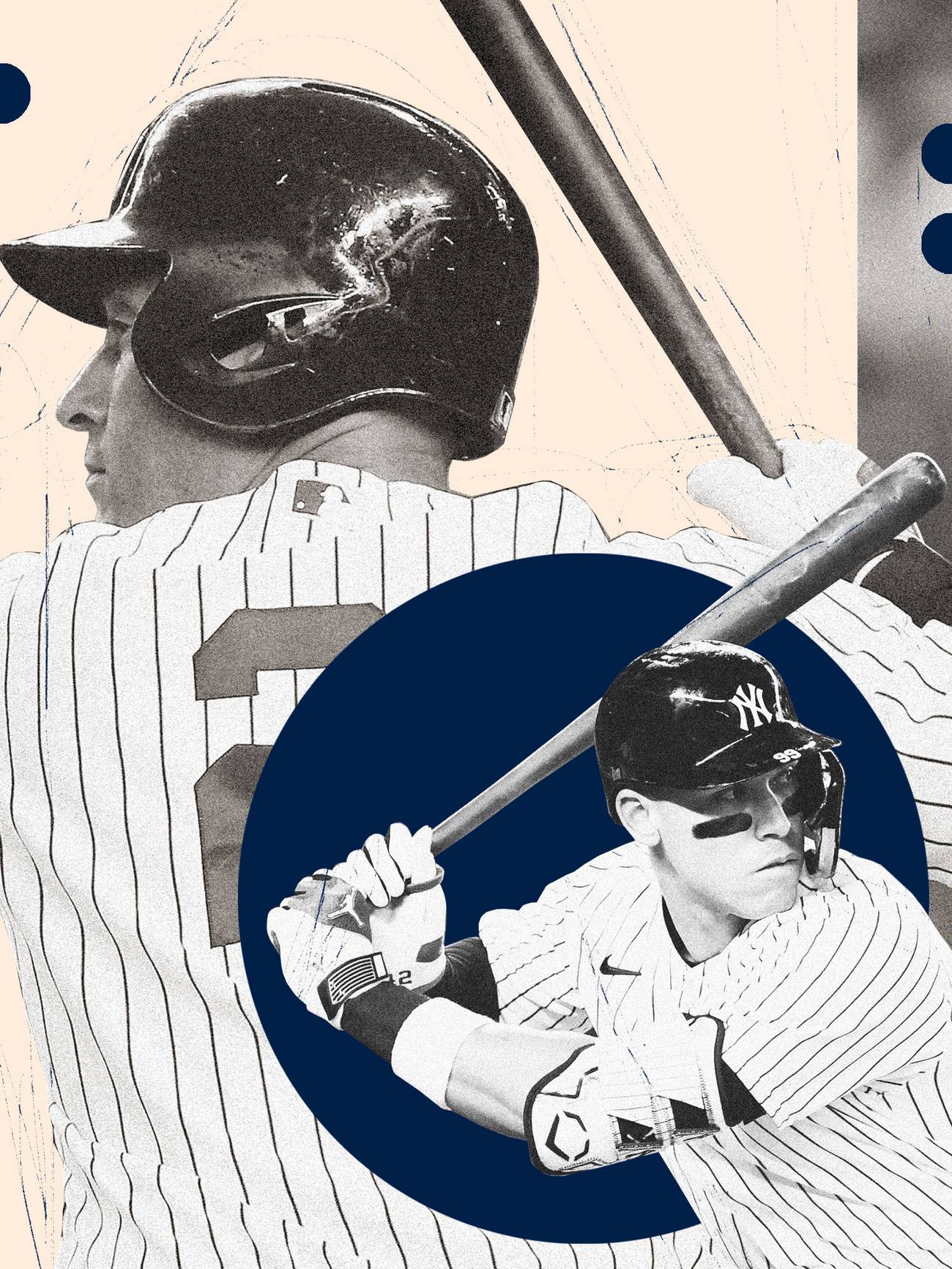

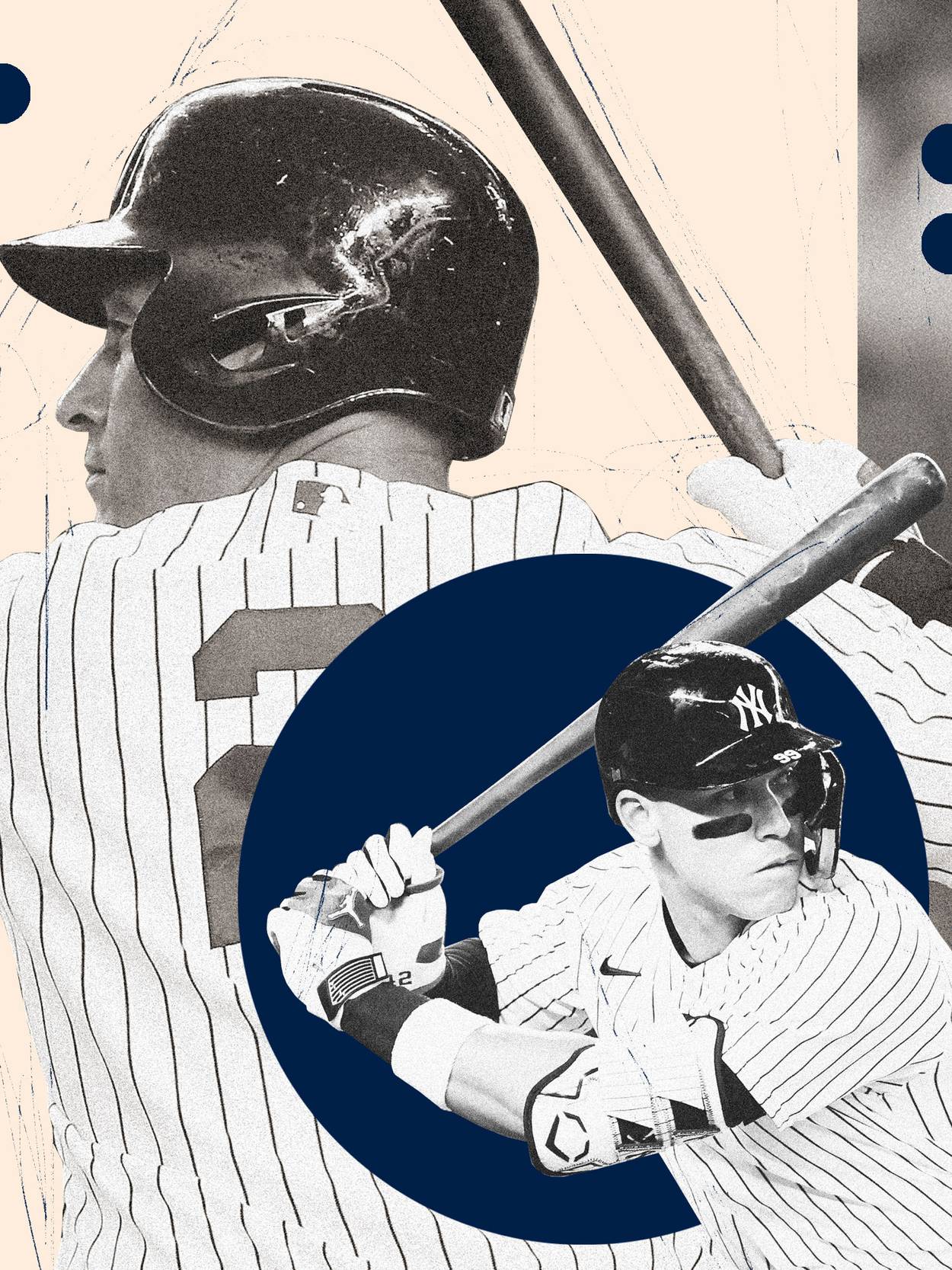

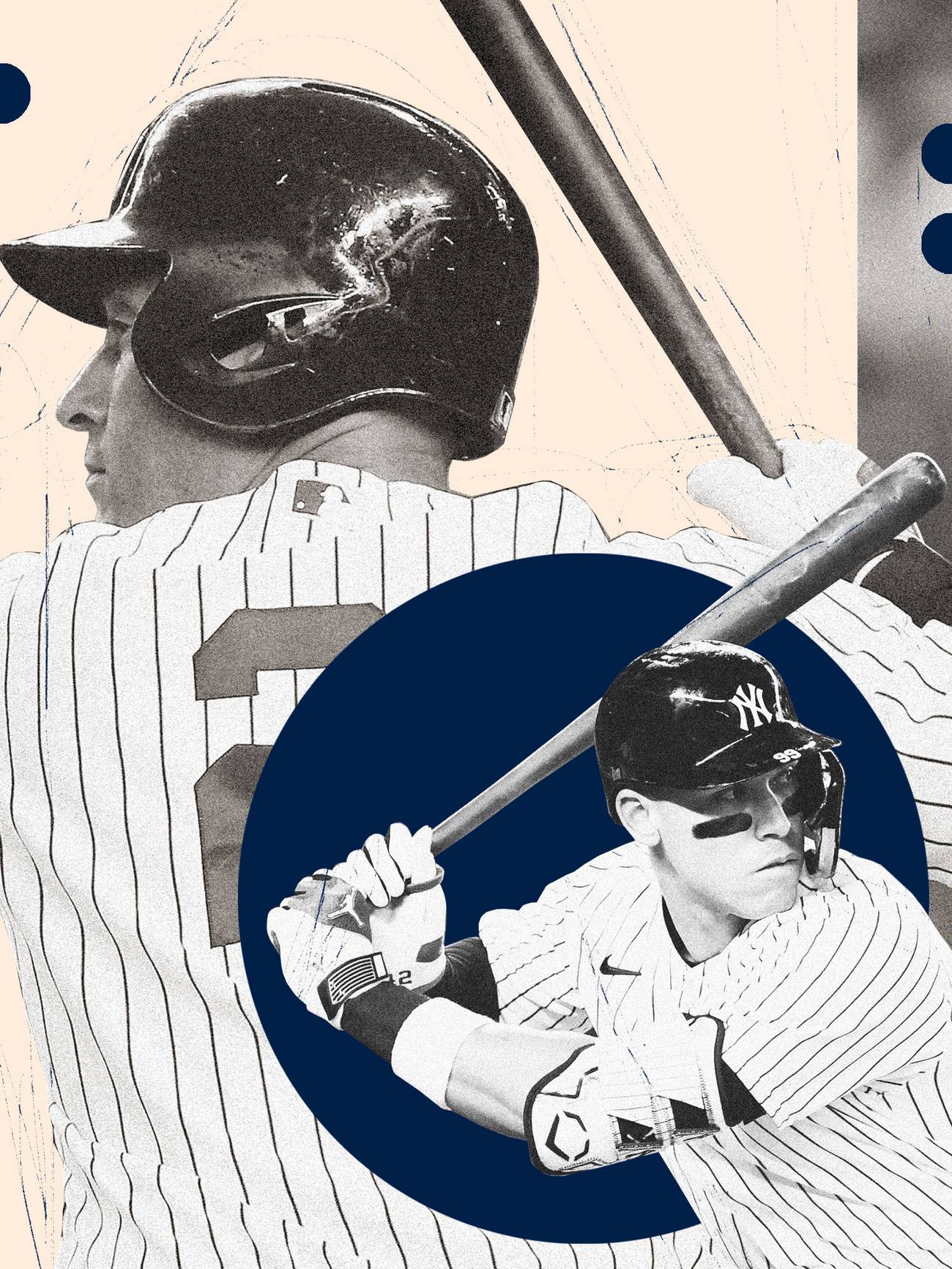

Judgement Day

Aaron Judge has assumed Derek Jeter’s mantle as the clean-cut, biracial face of baseball’s most famous franchise

When I was 7 years old I saw it on a television screen, sitting next to my father in his bedroom in Harlem. The “biracial angel” of my childhood, Derek Jeter, was trying to will the Yankees to victory in Game 7 of the 2003 American League Championship Series. With runners on first and third and the Boston Red Sox threatening to add to their 4-0 lead in the fourth inning, the Yankee captain fielded a tough hop on a scorched infield grounder from Boston’s Johnny Damon. The next moment is an unheralded career highlight, but one that encapsulated why Jeter was so beloved. Jeter scooped the ball, charged to second, and threw his own fastball to first. It was the hardest I had ever seen a shortstop throw a baseball. Even on TV, you could almost hear it whistle. The Yankees were still down four, but Jeter pumped his fist as violently as if he’d just won the game. And the Yankees did win. They mounted a comeback, beat the Red Sox off an Aaron Boone home run in extras, and went on to win the World Series.

Jeter was his era’s biggest—and most atypical—superstar. His teammate Alex Rodriguez was a more perfect talent: a true freak athlete and baseball prodigy, yet also insecure and inauthentic, and therefore unloved by the Yankee masses. “A-Rod” had an ego the size of Manhattan, memorably encapsulated in a photoshoot in which he posed kissing himself in a mirror. Jeter, by contrast, was unassuming. If Rodriguez could hit 40 and even 50 home runs a year, Jeter’s calling cards were the double in the gap, the timely home run, or the inside-out flare to right field. He was “clutch,” on offense and defense. If it is fashionable today to argue that Jeter was overrated, it’s because he was the beating heart of a Yankees team that was its era’s juggernaut. Just a cog in a world-beating machine, say the cynics, even if that cog once dated Mariah Carey.

It was a different time for Jeter, and for New York City, and for me. The city was allegedly being treated like hell by Rudy Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg, but I didn’t notice. The Yankees embodied traditional Republican ideals—no beards, one chain per player, and a dress code—and I, embarrassing to admit, loved it. We were good. We won. Other teams lost, and their fan bases could cry about it while walking to their minivans. Politically, I’m a progressive, and yet these Yankees were conservative—a clean-shaven, best-foot-forward, hard-working team of rich ball players. Wade Boggs rode police horses after the infamous 1996 World Series victory; Joe Torre allegedly gambled at the track during the day; Mariano Rivera was, in addition to being one of the most unique talents in the history of sports, something approaching a fascist. I couldn’t—and still can’t—get enough of it.

But the times have changed. New York has accelerated its transformation into a soulless, unlivable playground for the international rich, and the Yankees, with no championship for 13 years despite their $279 million payroll, are no longer the unifying behemoth they once were. Symbolically, they’re a product of that mayoral machine that has changed the city for the worse. After 9/11, the franchise became an element of Giuliani’s PR campaign to brand himself as “America’s mayor,” while during the Bloomberg era, the hollowing out of the city’s working and middle classes corresponded with the start of the Yankee World Series drought. Old Navy and Target opened stores in Harlem; the Yankees got bounced from the playoffs by the Anaheim Angels, twice.

And still, until his retirement in 2014, there was always Jeter. If something was going on in the late innings, Jeter was a part of it. If there was a big play to be made, Jeter almost always made it. The statistical revolution has shown that Jeter was a poor defender. Who cares? Newfangled defensive statistics don’t take into account how athletic and situationally crucial some of Jeter’s best plays were. Jeter is from the era where a jump throw was still a jaw-dropping highlight, instead of being sneeringly treated as proof of a player’s alleged slowness in getting to the ball. He did things that won big games that were far off of the stat sheet. When CC Sabathia opened Game 1 of the 2009 playoffs and spotted the Twins a 2-0 lead, it was Jeter who told CC “I got you,” and then proved it by tying the game for the Yankees with a home run.

Jeter was a master of the art of maintaining privacy in the midst of the media spotlight. We fans knew nothing about the real Jeter. We didn’t know who he hung out with. Unlike his teammate and frenemy A-Rod, he avoided bizarre controversies. People didn’t know Derek, but they admired him. He was in control of his own narrative, and that narrative was reassuringly impenetrable and bland, even corporate.

Today, Yankee fans have a new Jeter, or at least a would-be Jeter: right-fielder Aaron Judge, another biracial superstar. The reigning American League MVP—generally recognized, along with Japanese phenom Shohei Ohtani, as one of the two best players in baseball—is the new captain of the Yankees. If Jeter was physically unassuming, then Judge is a Hercules: 6-foot-7 and nearly 300 pounds of muscle, a towering, imposing figure who leads by sheer strength and force of example. Like Jeter, Judge is almost painfully normal. No bat flips, no scandals, no braggadocio—nothing interesting except the transcendent talent at crushing a baseball. You wonder if the man can even dance.

Like Jeter, Judge is almost painfully normal. No bat flips, no scandals, no braggadocio—nothing interesting except the transcendent talent at crushing a baseball.

Judge, who was adopted by white parents, sees himself as biracial, like Jeter. But Jeter played at a time when race was a considerably less fraught subject than it is today, at least publicly. Now, identity permeates everything, even for athletes. In the ESPN documentary The Captain, which aired last July, Jeter made the case for knowing himself as a Black man and a Black athlete, something he had never spoken about before. Episode 1 features Jeter discussing what his parents, Dr. Charles Jeter and Dorothy Jeter, told him about his identity. “My parents raised me and said, you’re a Black man. You’re going to deal with racism.” Judging from the grotesque story about a white man calling Jeter a “nigger” in his hometown of Kalamazoo, Michigan, his parents were right. Mrs. Jeter talks about the city with palpable disgust.

Jeter is the son of interracial marriage. His relationship with Black culture is evidenced by the many hip-hop songs—Young Jeezy’s “Go Getta,” for example—he would use as walk-up songs. On a recent appearance on the hip-hop podcast Drink Champs, he demonstrated his comfort around other Black men, and their appreciation of him. The Yankees’ late-’90s dynasty, after all, came at the end of one of hip-hop’s recurring New York golden ages. While Ghostface Killah rapped “ringleader, set it off, rap’s Derek Jeter,” Jeter was leading the Yanks to another World Series title, their third in four seasons. He played in the Bronx, the city’s roughest and poorest borough. His close friendship with Gerald Williams, the Black Mets and Yankees mainstay who died last year, is well-documented, as is Jeter’s fortunate noninvolvement in the events surrounding Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs’ alleged nightclub shooting.

Jeter, in other words, is Black, but the perception of him is that he’s mixed. Sportswriter Wallace Matthews described him as “racially neutral” and “almost colorless,” which was pernicious, but at the same time, you sort of knew what he meant. Until recently, Jeter didn’t seem interested in being understood by, or in ingratiating himself publicly with, Black people. Maybe he was responding to the “apolitical” stance of the ever straight-laced Yankees organization. Maybe he was reflecting the supposedly less political era that he made his bones in. Maybe his tenure as the Marlins owner made him realize that it was time to shift his public image and lean into his cultural cachet. As a Black man, Jeter never felt quite with us, even if he is one of us.

Besides, at the time, Jeter had better things to do than be Black: He was a true Yankee. The Yankees carry a ridiculous amount of psychic baggage. They command reverence, or at least attempt to, not just for the team but for the city, the country, and the entire sport of baseball. If Jeter had played for the Cincinnati Reds, there’d be no mystique. But he played for New York, and so he became part of a centurylong lineage of charming pinstripe stars. He’s painted on walls on Jerome Avenue next to Joe DiMaggio and the rest of the Yankee legends. In The Captain, ESPN writer Howard Bryant says, “I talk to the players all the time and they say, oh yeah, Jeter’s down.” I don’t doubt the other players feel that way, but for me, as a fan, nothing Jeter ever did was about his Blackness. Blackness was a suggestion, or something unspoken. It was never presented in the story.

The same goes for Judge, who signed a nine-year, $365 million contract extension with the Yankees on Dec. 7. Like Jeter, he has a guarded charisma, an inoffensive flair with just enough strut, though not too much. You’re supposed to see the intimidating, quiet confidence of someone who makes the right play with a remarkable frequency. Both Judge and Jeter handle the public eye with ease. They reveal nothing, but are the first ones journalists mob outside the locker room.

I, of course, love Aaron Judge, as I loved Jeter. He’s excellent, and getting better. It used to be possible to sneak a fastball by him if you jammed him. Now, he can turn on an inside pitch and crush it into the upper deck. His fielding is pristine, too. Against the Angels, on April 19’, he chased down a screamer in the eighth inning, keeping the game at 2-2. You knew he was going to make the play. He’s notorious for that.

For years, fans wondered whether Hal Steinbrenner, the enigmatic son of the impulsive and mercurial George Steinbrenner, the deep-pocketed owner who paid for the Yankees’ incredible World Series run in the late ‘90s and early 2000s, would ever take a massive financial risk on a potential franchise player. Now we know the answer is yes. Judge is inheriting the stratospheric expectations that Jeter created for any future Yankee savior. Probably, this is exactly the kind of challenge that Judge wants, even if there were offseason murmurings about him returning to his home in Northern California. The Yankee Way is all-encompassing, and it refers to a special mix of loyalty, classiness, and stoicism, a kind of brutally systematic success. Hardly any star player ventures off the grid in the Bronx. Distractions aren’t just a nuisance up there—they’re fatal. An excess of personal ego is simply unbecoming for members of a regal baseball franchise.

And yet, as a fan, I can’t help but ask: Does the Yankees’ gravitas, their conservatism, still make sense for what the franchise—and the city of New York—is today? Across American professional sports, superstardom is increasingly rooted in the identity of the stars themselves. Witness the marketing of Ohtani, Judge’s main MVP rival, as a sort of happy-go-lucky samurai basking in the Southern California sun, or even the recent embrace of political activism by Black NBA superstars like LeBron James. Fans need something to care about, to relate to, to argue and get angry about. It is one thing to be the clean-cut, stoic, team-first Yankees when the Yankees are on top of the universe, but this team is no longer riding police horses in front of euphoric fans; they’re coming up limp in the face of angry New Jersey men. I wonder if they know how empty—how unenthusiastic—the fans feel about the identity of the current team, and not just the fact that they haven’t won.

Judge seems to want to toe the organization’s partying line of tranquility, stating that his goal as a Yankee is to add to the running count of Yankee championships. That’s fair. Athletes, Black or not, do not have to be role models. Still, there’s a trope about mixed kids being more white than Black—one that I am hesitant to perpetuate, but which does occur to me when I watch Aaron Judge. In America, if you have a parent who is Black, you are Black. Maybe Judge doesn’t feel that way, or doesn’t care, or has other things on his mind. As a Black Yankees fan, I’d be lying if I said I didn’t want him to embrace his Blackness. Maybe I have to contend with the fact that just because the team isn’t what it used to be, that doesn’t mean the players have to change. The Yankees look like they will be good this year, but the powerful, almost totalitarian image of the old Yankees—the one that changed the city’s fanatic energy from a Mets-centric one to a Yankees-centric one—is gone. In its absence, it may be time for Judge to be someone.

Jayson Buford is a New York-based writer and a lifelong Knicks fan who loves Wu-Tang and his English bulldog, Joan. He still watches Woody Allen movies.