The works of Salo Wittmayer Baron after the Second World War and the Shoah are proof of his clear engagement in favor of the new American center that picks up, in Jewish history, where Spain, Italy, Holland, and Germany left off. Renouncing his previously positive view of the period of the ghetto, during which the state protected the Jews and imposed their inclusion in flourishing communities, Baron, in a “dramatic turn,” becomes an advocate for American liberalism, for voluntary and noncompulsory membership in local community, for spontaneous affiliation, a source of unlimited cultural wealth. He is convinced that, far from the protective royal alliance, “whatever shortcomings we may find in the modern democratic state, it ... leaves the decision to the Jews themselves.” From now on, long live a community in its American multicultural form, which peacefully coexists with other collective forms of social solidarity of the most diverse sort. That “cultural pluralism is and has been greatly enriching American culture,” a “factor working for mutual toleration within the Jewish group as well,” and protects it from authoritarian orthodoxy. There is thus no reason to “despair,” since for the first time, in this new center, “the Jews are no longer a minority like in Egypt, Babylon, Spain, Germany or Poland, but are part of the majority itself.”

Baron’s “rosy” presentation of American society coincides in many respects with that of his friend and rival Cecil Roth, published four years after “Ghetto and Emancipation” in the same Menorah Journal and titled “The Most Persecuted People?” Both comfortably settled in Anglo-Saxon universities, one at Columbia and the other at Oxford, do they share a tendency to avoid darkening Jewish history by becoming the heroes of the liberal and pluralist Anglo-Saxon world? Can this pacified view stand up to the reality of British history, which has hardly been always “rosy” for the Jews? Is this view confirmed by the history of today’s United States as a new center for a Jewish diaspora definitively immunized against secular persecutions, benign during the Middle Ages and violent with the advent of emancipation?

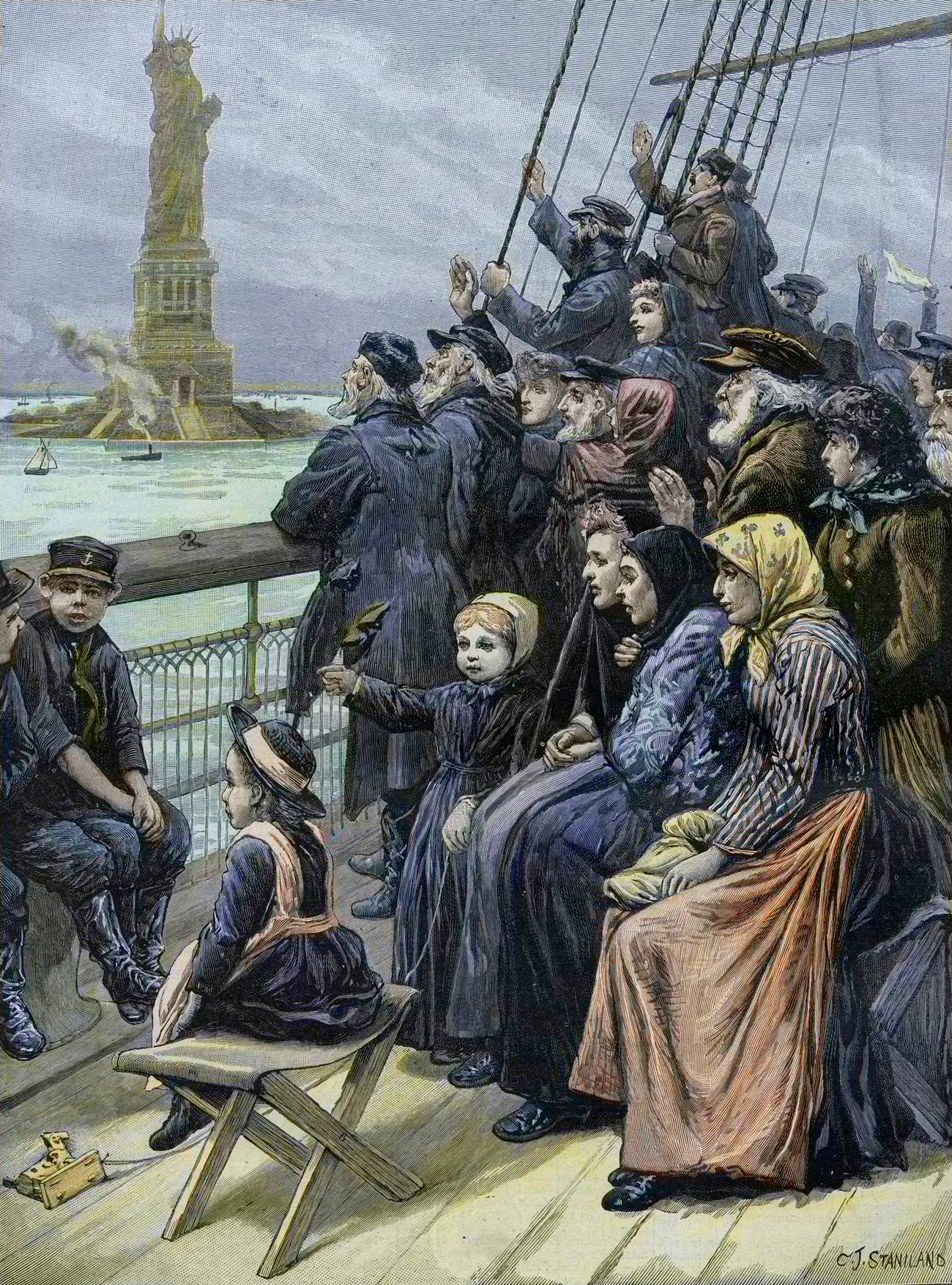

Salo Wittmayer Baron at the Eichmann trial, 1961Wikipedia

The most devastating reply came from Jerusalem. Let us not forget that Yitzhak Baer, in 1938, published a biting critique of “Ghetto and Emancipation” rejecting the optimistic vision of the diaspora formulated by Baron. For him, from the Middle Ages to modernity, Jewish history is really and truly the history of suffering. That is because two years previously, in 1936, Baer had just published a little book in German—which could not be more different from the perspective of Baron’s 1928 article and, up front, is radically opposed to the spirit of Baron’s three-volume Jews and Judaism: A Study in Social and Religious History, published the following year, 1937—as a continuation of his article in the Menorah Journal. One cannot imagine a worse refutation of Baron’s optimism than this little book, “Galut,” full of vitriol, by the eminent Jerusalem professor.

According to Baer, “for the Jews of the Middle Ages, any feeling of having a home had disappeared in exile.” His representation of this era so dear to Baron is resolutely negative. More generally, as Baer hammers it home, “all modern interpretations of exile lack any understanding of the extraordinary tragedy that it was.” For him, “exile is and continues to be what it never stopped being: a political enslavement that must be completely abolished.” It is the very idea of galut that is challenged, as much in old Europe as in the United States, meaning, in exile: According to this view, diaspora, life outside of Israel, is harshly condemned. We can discern in this affirmation a response to Baron’s 1928 article that foreshadows his ruthless critique in 1938. From antiquity to the Middle Ages, from the splendor spanning Spain to Germany in the 1930s, for Baer, “the suffering of the diaspora” is such that “the Jews became a persecuted group everywhere in the world. The Middle Ages, a period of prosperity for Judaism according to Baron, is perceived by Baer as a long procession of “massacres,” “expulsions,” and “martyrdoms” that herald the violent acts of the Nazi period.

This short work published in 1936 acts as a warning: As though predicting the coming of the Shoah during the victorious years of Nazism, Baer implores the Jews to abandon their illusions of the mere possibility of a happy and peaceful life in diaspora. Baron’s name is never mentioned; it nevertheless seems to exist between the lines, in the background, before emerging explicitly two years later in his radical accusation.

Baer denounces diasporic life as a deadly attack on the life of the Jewish people. For him, “the Jewish question in Spain in the fifteenth century teaches the modern observer the horribly inevitable nature of the historical conflicts that, manifestly, can only be reproduced under eternally new forms.” Alerting German Jews while Baron still shows himself optimistic, he writes, evoking the Inquisition, “this process happens with the tacit or explicit approval of a cultured Europe, accompanied at the most by some occasional and ambiguous shows of compassion.” A word to the wise!

Baron, “theoretically, at least, was a diaspora-oriented historian. ... In an age of intensified anti-galut trends, he became one of the authoritative spokesmen of a pro-galut philosophy ... and he also declared galut a permanent feature of Jewish existence and destiny.” On the opposite side, Baer is persuaded that “everything that we have accomplished in foreign lands was a treason of our own spirit,” thus condemning in advance any and all diasporas, including that of American Jews who, just like their predecessors, consider themselves “home” in America. Salvation demands the end of exile, the saving return to Zion.

One cannot imagine a more radical opposition than between Baron the diasporist and Baer the Zionist who sets off warning bells for the threatened German Jews, as for the Spanish Jews before them—while Baron continues to show confidence in the resilience of all diasporas, convinced that even the German Jews, particularly exposed by the rise of Nazism, will find the means to preserve their lives as well as their spiritual wealth.

In response to “Galut,” Baron publishes in 1942, during the worst of the Shoah that radically belies any optimistic Baronian diaspora, his three volumes of hymns to the community, sung as though a protective and creative force for all times that—despite all of the suffering endured in diaspora—justifies happiness in American exile. Baron is far from having lost this ferocious battle against Baer. Many rise up, with him, against this irreparably negative view of exile, of life in the diaspora, and especially at the heart of American society that has become, with Israel, the center of Jewish life. For Michael Walzer, for example, “the establishment of a genuine liberal and pluralist society in the United States and of a Jewish state in the land of Israel mark the end of exile. But they only make possible, they cannot guarantee, our release from the politics of exile.” For Walzer, the negative view of exile according to Baer is nearing its end when the place of exile itself is metamorphosed into a legitimate “home” that feels good to inhabit.

In 2000, Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, Baron’s most brilliant student, is chair of Jewish studies at Columbia University. He writes a long preface to the French translation of Baer’s vehemently critical work, whose attitude toward Baron’s implicit ideas is hardly charitable. A staunch New Yorker whose entire existence has been in diaspora, he reveres his master Baron. While he confesses his admiration for Baer’s incontestable erudition (Baer authored a masterful study of Jews in Spain), it is to Baron’s posterity that he remains faithful. Yerushalmi does not hide his irritation. Author of the fabulous From Spanish Court to Italian Ghetto, he does not understand the depreciation of the Middle Ages in Baer, who knows more than anyone else the splendor of the Spanish Jews at this time, on which he is the most renowned specialist. On several occasions, Yerushalmi considers his rejection of exile “excessive,” which leads to a “feeling of unease” due to the “absence of balance in the proposition,” all the more given that “the majority of Jews still live outside” Israel. He nevertheless concludes his text with this strange question: “The questions raised by Baer have not lost their relevance—‘galut’ or ‘diaspora’? What are the relationships between diaspora and center?” This final question picks up Baron’s interrogation but reverses it, since for Baron the United States has become the new center, whereas for Baer only Israel can act as a center given the illusions of diaspora and its misfortunes.

Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, 1989Wikipedia

These questions are at the very least surprising coming from Yerushalmi, whose work, unlike Baron’s, remains practically silent concerning the modern era. Yerushalmi in particular, unlike his mentor, has deliberately ignored the unique history of American Jews, considering it unfruitful. On this point he moves away from Baron, all the more because he does not participate in community Jewish life or in its philanthropic organizations, considered vital by Baron, and thus voluntarily neglects this society that he does not find particularly favorable to the study and enactment of sacred texts. Baron bitterly criticizes him for it. As Yerushalmi browbeats a student working on an American Jewish thinker by exclaiming: “Why do you work on the history of American Judaism? Is the history of American Judaism so crucial in the eyes of Europe, Asia, or even Africa?” Baron replies: “You are talking about the biggest Jewish community in the world.”

We are left with a mystery that we only wish to mention. Yerushalmi, just like Baron and Baer before him, studied the logic of the Shevet Yehuda Salomon Ibn Verga’s major work. Baron found in it a confirmation of his description of the Jews as servie camerae, servants of the treasury, of the state, protected in a way by this unique tie to the royal state, which never initiated pogroms. For him, the state, having become almost absent, loses its protective function in an American society that is based on a pluralist and liberal democracy where Jews constitute one community among others, a community whose survival no longer depends on the state, but indeed on its insertion into this “nation of nations.” From then on, for Baron, the royal alliance whose merits are overly praised by Ibn Verga becomes obsolete with the emergence of a type of horizontal alliance unique to American society. The Jews abandon their status as servie camerae and take advantage of the happiness of American society. The Spanish model loses its function in a society that, unshaped by the state, ignores any unifying nationalism and gives way to peaceful relationships among neighbors.

Baron’s student Yerushalmi remains silent on this point. He has spent his life drawing all possible conclusions from Ibn Verga’s work, closely following the meanderings of his thought, and has so hesitated to see in the royal alliance a simple myth empty of any reality that he hardly commits to this point. Far from the sociological and comparative approach used by Baron, he sticks to a meticulous study of the great texts that punctuate Jewish history and only addresses the modern period through brief allusions, without undertaking a comparative analysis of the implementation of a kind of royal alliance in today’s societies. He refrains from any empirical analysis of the sort Baron introduced through his use of a traditional history of the Jews between old Europe and the United States. He wonders: Does the royal alliance retain its logic and preeminence in the context of a weak state, of the pluralist and liberal society with diverse communities in the United States, a quasi-empire similar to the former Austro-Hungarian Empire, so profoundly decentralized? Are the Jews better protected from antisemitism even if they cannot entirely count on the benevolence of a weak state? Is their happiness better ensured here, as long as they prefer their local alcove to an active presence at the top of the state?”

The questions raised by Baer have not lost their relevance —‘galut’ or diaspora?

The analogy, or parallel, between the Spanish model or even the French model and the unique case of American society, sheds light on diverging paths that Jews follow in opposite governmental contexts. Loyal to Baron’s thesis, Yerushalmi validates in his way the complex vision of Jewish history put forth in 1928 in “Ghetto and Emancipation.” In his tremendous and definitive From Spanish Court to Italian Ghetto, written under Baron’s mentorship and for which the latter curiously wrote a preface without much enthusiasm, Yerushalmi follows step by step the exceptional life of Isaac Cardoso, who hoisted himself, as a converso, to the top of the Spanish state by imposing himself as an official doctor, enjoying all the attributes of power. A high-ranking official benefiting from his public status, Cardoso singlehandedly embodied these “Servants of Kings and not Servants of Servants” whose role at the heart of the absolute monarchy Yerushalmi theorizes. In this way, Cardoso anticipated the exceptional destiny of these state Jews who, in Spain but even more so in France—whose state is so strong—put all of their energy into serving the state by occupying a preeminent position at its core.

But contrary to these Jews who devoted their life to the state and identified with its rationalist logic, Cardoso, against all expectations, suddenly left his position serving the state to take refuge in Verona’s ghetto and become a doctor for the poor. It was as though, to validate Baron’s perspective, his immersion behind the protective walls of the ghetto prevailed over the glory of serving the state; as though, like the American model celebrated by Baron at the same time as Yerushalmi is writing his dissertation, the ghetto, or local community, revealed itself to be more suitable to a fulfilling Jewish life, as much in Italy, whose state was weak, federal, and decentralized, as in the United States, with an equally weakened federal state. As though, finally, in Spain’s monarchy just like in France’s republic, or even in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, access to preeminent roles for Jews could only be fatal for them, to the point that the American situation of insertion into ghetto communities that has long prevailed was much more advantageous than having access to federal politico-administrative structures.

It was as though, to conclude on this point, Spanish, French, or Austrian Jews were deaf to the threat that Stefan Zweig issued in 1936, then again in 1938, at the exact moment that Baron published his first three volumes of A Social and Religious History of the Jews as a development of his “Ghetto and Emancipation”: “There is nothing that has stirred the anti-Semitic movement as much as the fact that the Jews made themselves too visible in various countries, in various aspects of political life, and all too often as leaders.”

Zweig does not want Jews to participate in politics in a “leadership position” and advises them to adopt a “certain reserve,” to make do with “serving while staying at the second, fifth, or even 10th rank, and to never take the top position, the most visible.” Baron, concerned that the Jews stay within their local communities, can only approve this recommendation, just like Yerushalmi, who recounts Cardoso’s destiny, preferring the ghetto to the splendors of the state.

Is Zweig familiar with Heinrich Graetz’s ideas? Has he read Baron’s books or articles, his 1928 text, the three volumes that have just appeared in 1936, the same year that he expresses his opposition to the presence of Jews in preeminent positions within the state? When he considers that “the feeling of insecurity and inferiority lies in wait for the Jewish people, always surrounded by hostility, always oppressed, always on the defensive,” he is situating himself in Graetz’s current of thought and implicitly embraces the lachrymose theory of Jewish history, denounced by Baron, but adds the decisive element that this hostility is stirred by the presence of Jews “at the forefront” of the state. Neither Baron nor Yerushalmi supports such a proposition, namely that the royal alliance that ties the Jews to the state and pushes some among them, such as Isaac Cardoso, to occupy a preeminent position within the state inevitably provokes antisemitic hate.

When Cardoso rises, thanks to his competence, to a function that confers upon him high visibility, he does not trigger, according to Yerushalmi’s analysis, any violent antisemitic hate. Be that as it may, after having risen to the top of the state while hiding his true identity as a practicing Jew, Cardoso flees this Spanish state that mutilated his personhood to take refuge in the Verona ghetto, where he finds protection by returning to a soul-saving Judaism. This is evidence that the royal alliance is hardly synonymous with happiness, that it can reveal itself to be, as Zweig emphasizes, dangerous.

Under the influence of Baron’s ideas in praise of the medieval ghetto in which Jews, though benefiting from public status, had hardly any access to the state that protected them, Yerushalmi hesitates. Cardoso proves both the functional nature of the royal alliance that allows his social ascent and its ultimate failure. In Yerushalmi’s mind, happiness does not lie at the end of a strategy that ultimately and decisively reveals itself to be a myth, a lure facilitating all tragedies, as shown by the Nazi example—only mentioned indirectly, even less frequently than in Baron—all the while remaining weary, like Baron, of a lachrymal history. Nevertheless, loyal to the historical perspective traced by Baron, Yerushalmi believes that the vertical alliance, despite its fluctuations, its inconsistencies, the royal infidelities, and the Jews’ erroneous beliefs, only had merit in the pre-modern period, during which it avoided as best as possible tears and suffering.

Furthermore, when all is said and done, Yerushalmi doubts even more than Baron its functional nature, given how Manuel, the “gentle king,” preferred to ignore antisemitic violence, an observation that also ruins the optimistic view of the Middle Ages that Baron defends tooth and nail. Paradoxically, one might even argue that, against his will, Yerushalmi turns away from his Baronian inheritance by justifying the lachrymose view of history, including during the Middle Ages—a prosperous period in the eyes of his mentor. Yerushalmi is more than skeptical as to the protective role of the royal state. Even in this period, happiness seems to reside more in the margins, in the return to the ghetto. Also, in the modern era, at the heart of the Upper West Side of New York, a kind of broad and peaceful urban community that escapes antisemitism is untouched by the grip of the state or by the question of a vertical alliance, a kind of Verona ghetto transposed to the goldene medine that meets Baron’s and Yerushalmi’s expectations.

From then on, Baron’s solution becomes more prudent: Stay on the sidelines, do not lay claim to the glory of serving the state in a society where it no longer plays the ambiguous role that it did under absolutist Spain. Consciously or not, Baron and Yerushalmi seem to heed Stefan Zweig’s advice. For them, in the United States, the royal alliance loses its historical function, and Jews return to their civil society, their community, and abandon the summits of the state. According to this logic, the long quasi-nonexistence of state Jews in the United States prevents the eruption of political antisemitism. By staying away from power, by preferring to be locally rooted, American Jews preserve a “happiness” devoid of glory but shaped by a joyful and fecund community life, favorable to “knowledge,” devoid of “tears,” and unaffected by the political antisemitism that so severely affected the Jews in French-style states, or even, as in previously, their colleagues in the Austro-Hungarian Empire.