Jews have dedicated prayers to the welfare of reigning monarchs since biblical times, when Jews exiled from Jerusalem to Babylonia reached out to the Prophet Jeremiah for guidance on navigating their relationship with their new rulers. In the British Commonwealth, Jews in modern times commonly incorporate such prayers into Shabbat services, expressing hopes for the king’s or queen’s well-being.

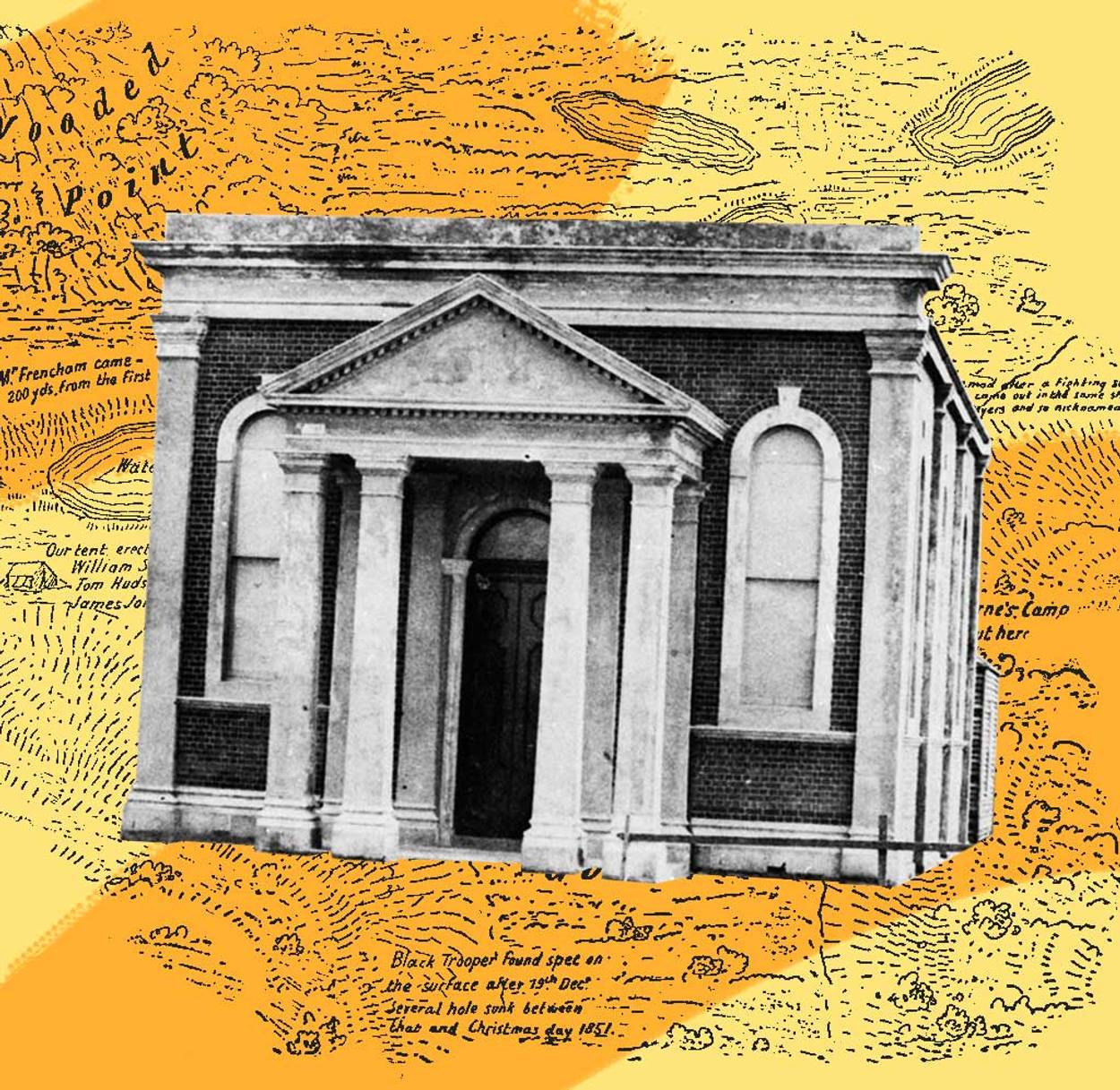

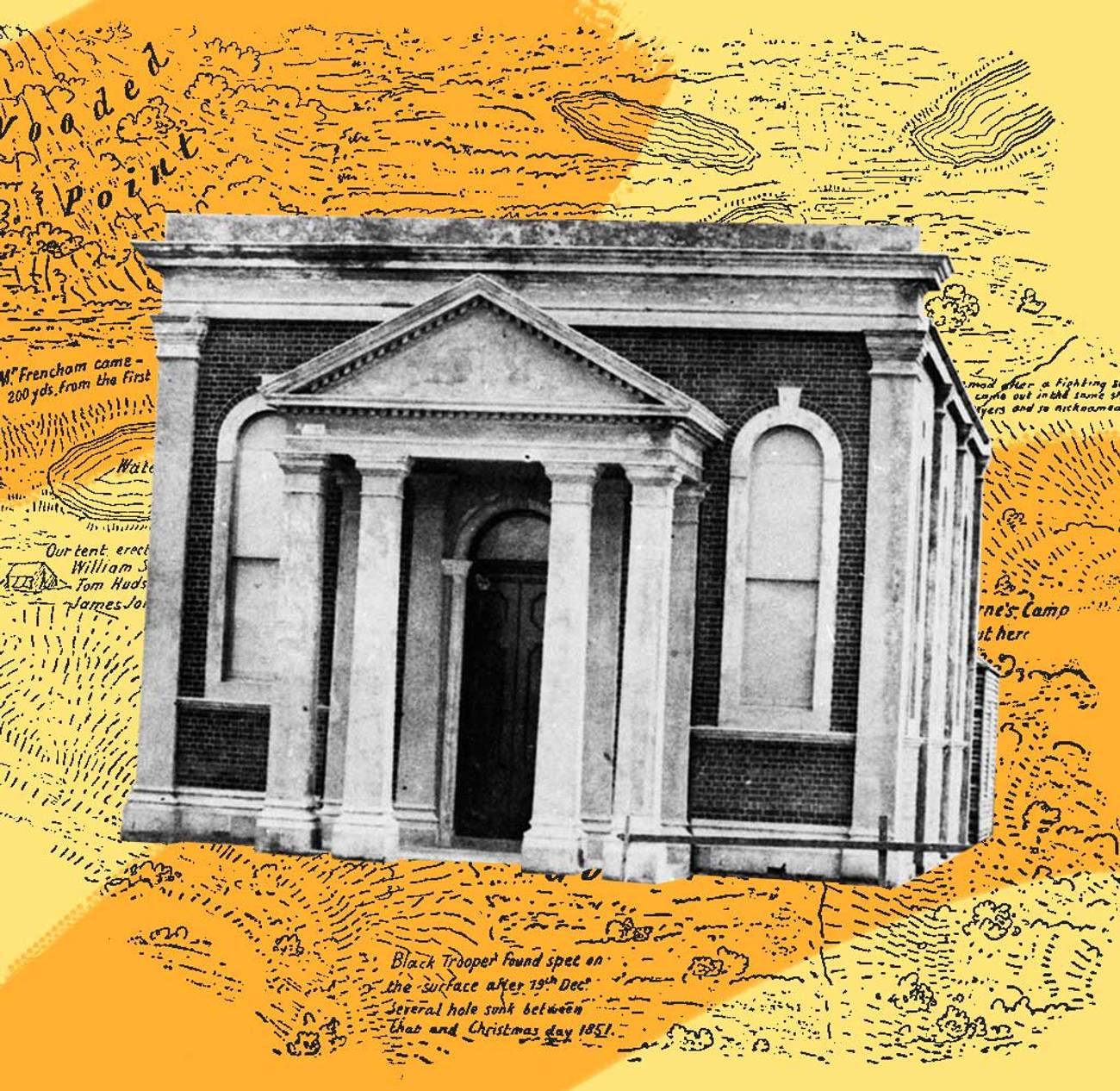

A unique manifestation of this practice can be seen at the Ballarat Synagogue in Australia, an hour’s drive from Melbourne. The synagogue proudly displays two sizable wooden plaques featuring the prayer for the queen’s well-being, one inscribed in Hebrew and the other in English, commemorating Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee in 1887.

Ballarat, located in the Australian state of Victoria, rose to prominence during the mid-19th century after gold was found there in 1851, igniting a gold rush; over the next year, the city drew approximately 90,000 people from around the world. At the peak of the gold rush, between 1852 and 1853, Ballarat stood as the world’s wealthiest alluvial goldfield.

The city attracted Jews from England who were seeking their fortunes as well as other European Jews who were escaping antisemitism. In 1853, a minyan was established on the Ballarat goldfields for the High Holidays and by 1859, the town boasted a Jewish community with more than 300 men. In 1861 it consecrated its synagogue. I’ve always had a personal interest in the synagogue because my great-great-grandparents moved to Ballarat from America in the 1800s as part of the gold rush, and are buried in the large Jewish section of the Ballarat cemetery.

After 162 years, the Ballarat Synagogue continues to host a monthly Orthodox Shabbat service, including a prayer for the well-being of the British monarch.

“It’s been my synagogue since I was a kid,” said Ballarat Synagogue President John Abraham, whose family moved from North England to Australia in the 1800s and settled in Ballarat during the gold rush. “My father was on the board for many years and was treasurer. My grandfather and my great-grandfather were also on the board. My great-grandfather was one of the first married in the shul.”

The founders of Ballarat Synagogue were a diverse group: miners, businesspeople supplying the mining community, and participants in the 1854 Eureka Stockade—a pivotal event advocating for miners’ rights that is a well-known part of Australian history. Charles Dyte, a key figure in the 1854 Stockade, was also a founding member of the Ballarat Synagogue, highlighting the interconnected roles that Jews had in shaping Australian history.

Ballarat Synagogue is the oldest continuously used synagogue on Australia’s mainland. (Tasmania’s two synagogues, in Hobart and Launceston, predate it by a few years.) The synagogue has five Torahs, including one from the 1850s.

Yossi Aron, who has written books focusing on the history of Jews in Australia, told me: “Ballarat was a very important community. At one stage it was the frummest community in Australia. The Beit Din of Victoria even sat in Ballarat.”

While there were Jewish miners involved in digging for gold in Ballarat, a significant number chose to provide services to the mines.

“There were some Jewish miners, but the work was a bit hard for European Jews,” said Aron. “They became the providers. People came to Ballarat looking to make their fortune, but some decided it would be better to be the wagon drivers, the people who brought in the merchandise that they sold at profitable prices to the miners.”

During the initial decade of the gold rush, a quarter of Ballarat’s shopkeepers were Jewish, among them, members of the Ballarat Synagogue. It was such a vibrant community that it employed a rabbi.

But it’s been decades since the synagogue has had a permanent rabbi—since 1943, said Abraham.

Today, Abraham resides in the former rabbi’s residence, located next door to the synagogue, a property he purchased from the synagogue nearly two decades ago, ensuring that his family’s ongoing engagement with a historic building continues.

“After the last rabbi finished, the rabbi’s residence was rented out for nearly 60 years,” he said. “Nearly 20 years ago, the board finally came to the conclusion that without spending lots of money which we didn’t have, we needed to sell it. It hasn’t been used by the shul [for a rabbi] in 60 years.”

The Ballarat Synagogue is currently going through a renaissance. While for many decades it was only open on High Holidays, about 15 years ago, Max Lasky, a resident of Melbourne, began coordinating monthly Shabbat services at the shul. It’s not just local Jews who attend these services; Jews from farther afield in the wider goldfields region—in the cities near Ballarat that also had gold rushes, such as Bendigo—will pop in for services, as well as occasional Shabbaton groups from Melbourne. I visited the synagogue recently for one of these Shabbatons, and the pews were full.

“There is heritage in Ballarat, [and it’s nice] to just sit there and reconnect to the gold rush. It’s quiet and its peaceful, there’s meaning, and it gives me a chance to express my Yiddishkeit,” said Lasky.

With capacity to seat a few hundred, there are 40 paid members at the synagogue. “There are not many Jews living in Ballarat, a couple of big handfuls, but we have a big diaspora that have connections to the shul,” remarked Abraham. “They come back quite often.”

The main synagogue sanctuary recently underwent extensive renovations, aimed at restoring its history—the synagogue’s first major facelift in more than 100 years.

The renovation, amounting to over 300,000 Australian dollars ($194,000), received partial funding through a grant from Heritage Victoria, the local government body responsible for the conservation and promotion of cultural heritage. Additionally, private donors and Jewish foundations, primarily from Melbourne, contributed to the restoration. The extensive renovation included new carpets, a fresh paint job, and repairs to the bimah and the chandelier. An arborist also inspected the 160-year-old Canary Island pine tree outside the front of the building, planted in 1867 by the great-grandfather of a current synagogue member.

In March 2023, when the renovations were completed, the synagogue hosted a rededication ceremony to celebrate the revamped building. Over 100 people attended, many with personal and historical ties to the synagogue.

“One of my objectives when I first came into this job [as president] was to keep the shul alive,” said Abraham. “It’s stronger now than it’s been in a long time.”

The synagogue is actively strategizing for its future, with Mark Schatz, the current treasurer, focused on planning further restoration efforts. This includes the Paul Simons Function Hall, situated on the same property as the Ballarat Synagogue, but in a separate building from the main sanctuary; it was not part of the initial scope of completed works.

Schatz received approval in November from Heritage Victoria informing him that the hall has been accepted into an initial stage of heritage listing, opening the door for additional heritage preservation efforts at the synagogue in the coming months.

“We would like to try and have a future fund, so that we know that in 15 to 20 years the synagogue’s future is secured, ” said Schatz. “We are interested in restoring the building, not changing it.”

The synagogue committee and community know the importance of preserving such a historic and important building.

“Once these places are gone, they don’t come back,” said Schatz. “I think that the Hebrew congregation in Ballarat, during the times of the goldfields, were important contributors not just to the social fabric, but also to civil life. I think that for that reason, the shul needs to be maintained so that the impact that the Jewish community has on the goldfields’ region continues to be recognized.”