Searching for the Roots of the ‘New Year for Trees’

Some Jews believe Tu B’Shevat grew out of a pagan festival

“Queen of heaven, breather of the first fire, the great Tree of Life, Asherah!” An emphasis on the ancient goddess Asherah’s final syllable was a rallying cry, followed by “Woo!” from multiple attendees at the JeWitch Collective’s 2016 Tu B’Shevat. Sitting underneath towering trees in Northern California, the group listened to Rabbi Lynn Gottlieb’s story on the Canaanite goddess, who was associated with sacred trees and, sometimes, the Tree of Life and Tree of Knowledge. Due to this arboreal association, some modern-day Jews believe Tu B’Shevat originally honored Asherah.

Tu B’Shevat falls on the 15th day of the month of Shevat. It is generally believed that the holiday took shape in the second century and was first recorded in Mishnah Rosh Hashanah 1:1. Multiple sources cite the first Tu B’Shevat Seder as a Kabbalistic celebration in the 16th century.

But some believe there’s more to the story. The Tu B’Shevat page for Machar—a secular humanist synagogue in Washington, D.C.—claims the holiday’s origins are in “stories of Asherah [Astarte], wife of the god Elohim (another name for Yahweh). Her symbol is the tree, so this is often called the New Year for Trees.” The Congregation for Humanistic Judaism of Fairfield County in Connecticut, Boston Workers Circle, and The Cultural and Secular Jewish Organization all state that Tu B’Shevat originated as a pagan festival honoring Asherah.

“Tu B’Shevat represents one of the three agricultural holidays—along with Sukkot and Shavuot—that reveal the matriarchal roots of Judaism,” said George Rockmore, a public relations volunteer with the Congregation for Humanistic Judaism. “Tu B’Shevat originated in a pagan festival honoring Asherah, goddess of farmers and fertility. Our [Tu B’Shevat] Seder celebrates the importance of our stewardship of nature, gathering to share food, music, and fellowship.”

Gottlieb hopes to reclaim those matriarchal roots by telling stories of forgotten female figures in the Hebrew Bible and biblical history, and Asherah is one of the foremost ancient goddesses in Canaanite—and Israelite—lore. Biblical scholars believe that our ancient ancestors thought of Asherah as the Mother of the Gods and represented fertility, motherhood, and rebirth. She was considered the wife/consort of Yahweh (or Baal, for Canaanites). The goddess was represented most commonly by Asherah poles—stylized trees or poles honoring her that were erected at Canaanite and Israelite religious sites, including the Temple Mount (2 Kings 23:13-14).

“Asherah is one aspect of trying to understand how people thought of the Feminine Divine throughout Jewish life and especially throughout the diversity of women,” said Gottlieb, a pioneering feminist rabbi and author of She Who Dwells Within: A Feminist Vision of a Renewed Judaism, which touches on Asherah. “I’m making her story and ceremonies available for people who are looking for the Feminine Divine.”

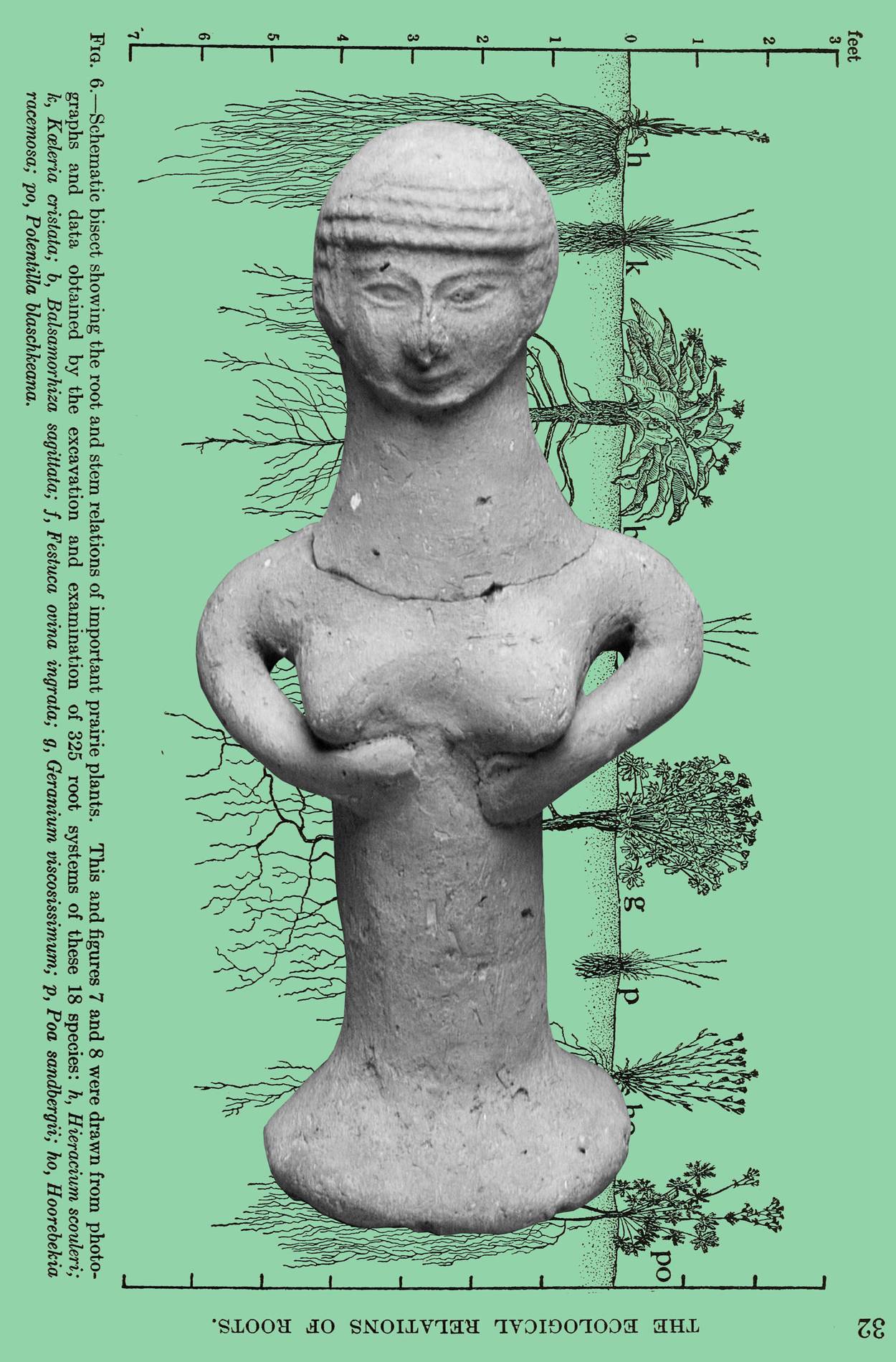

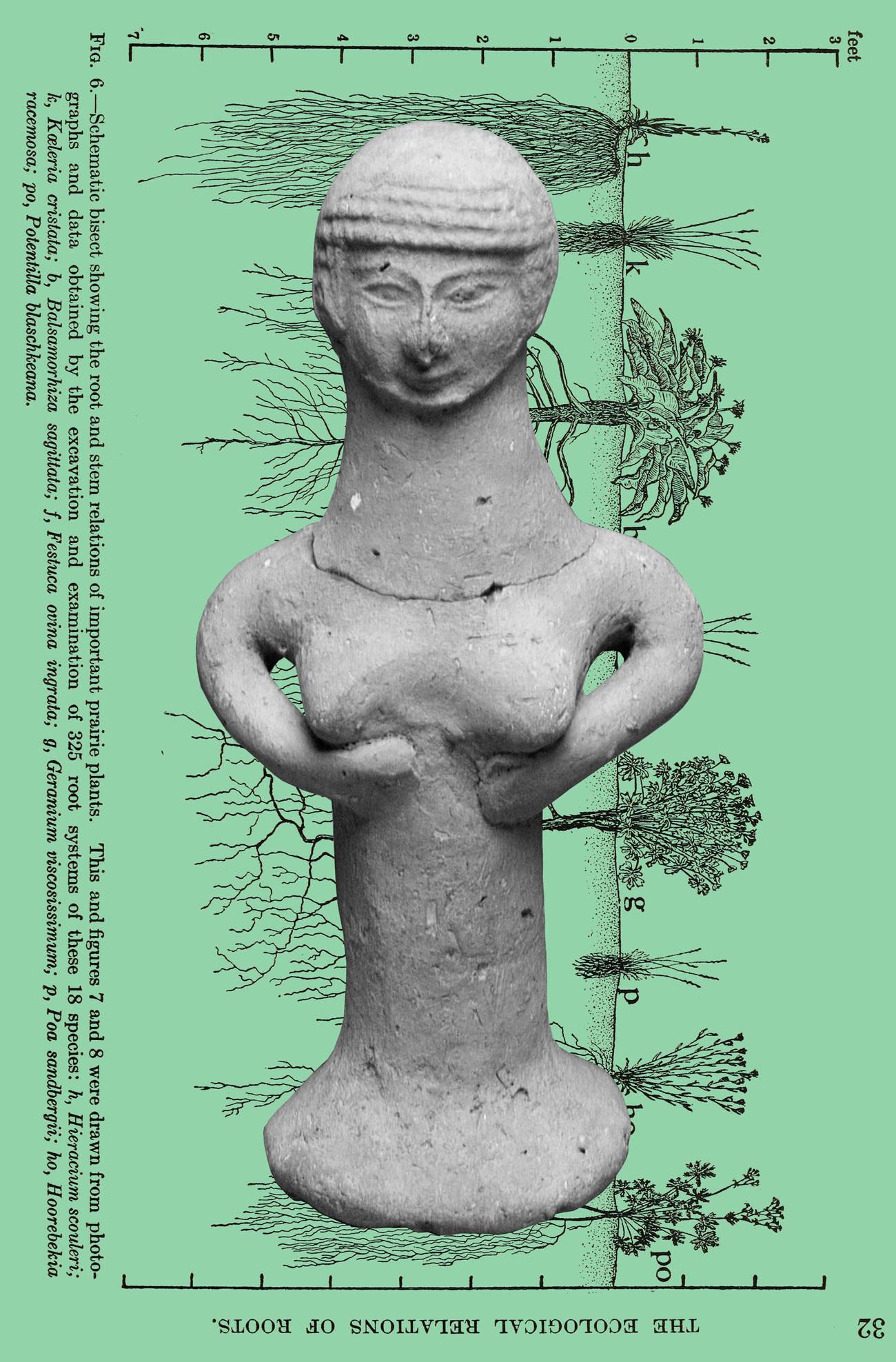

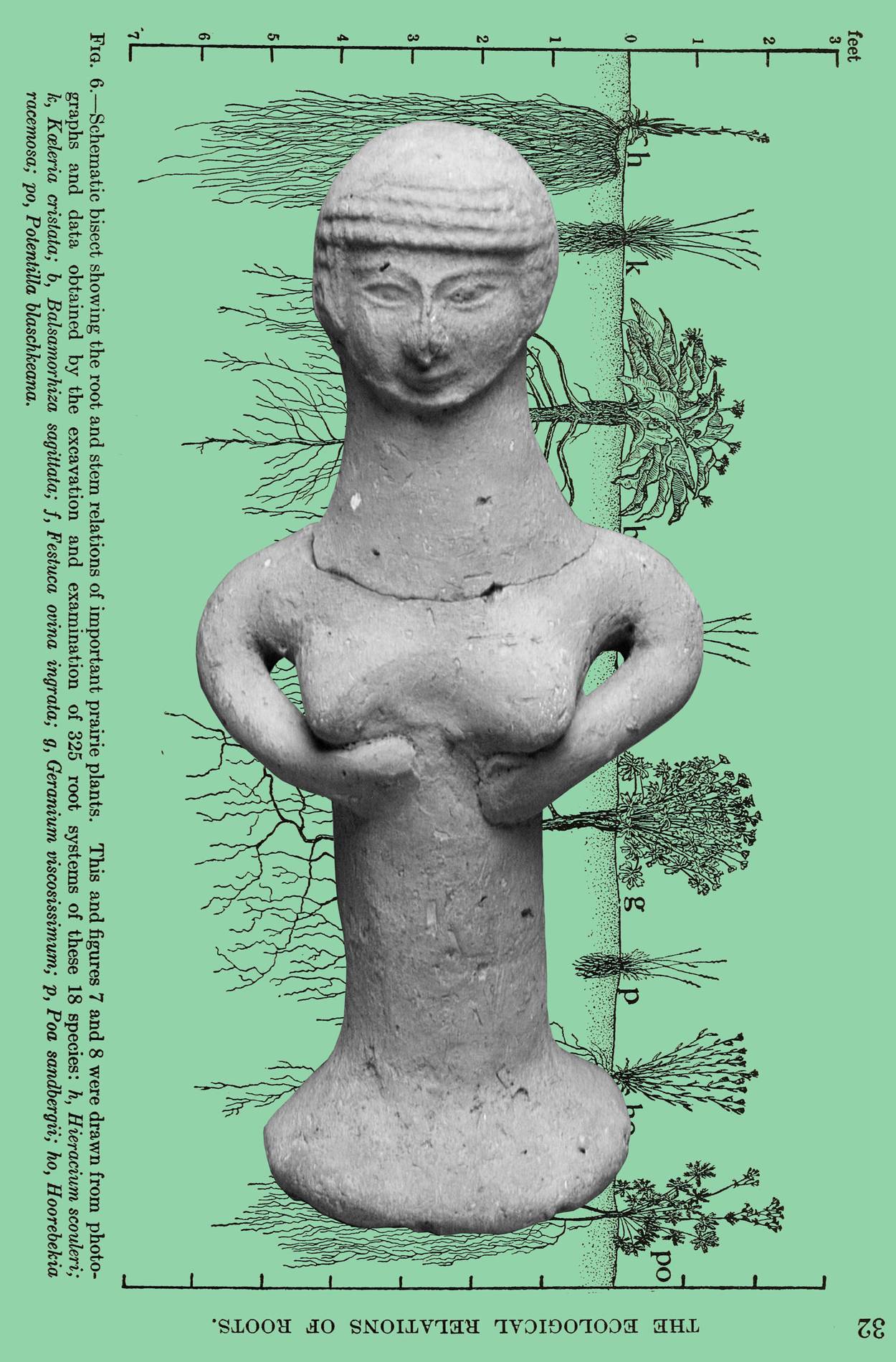

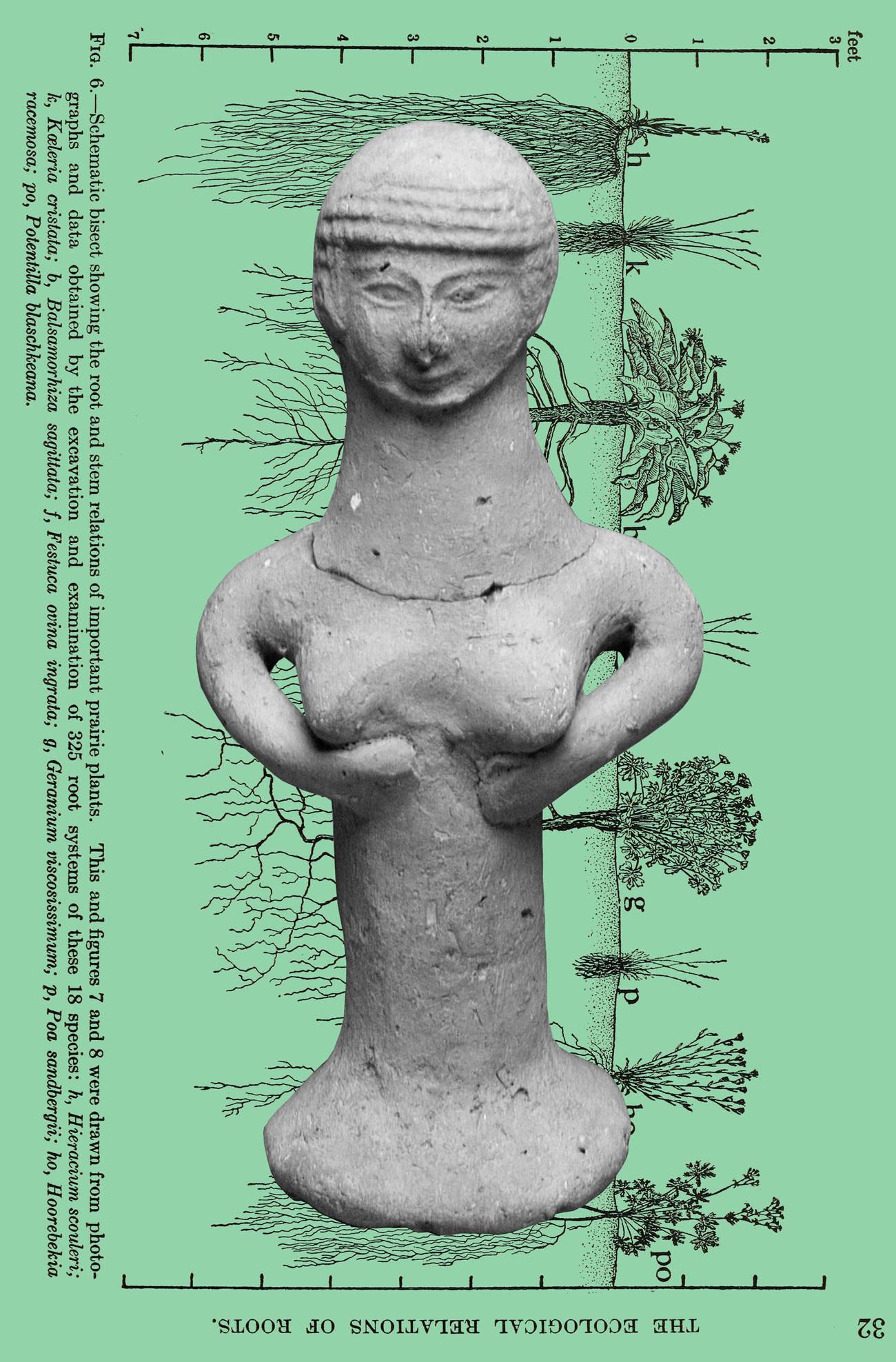

Biblical scholars think that our ancient ancestors adopted the goddess due to their proximity to the Canaanites. Susan Ackerman—a professor of religion and women’s gender and sexuality studies at Dartmouth College—said there is some evidence that Asherah was worshiped in temple centers in major urban areas where Israelites resided, like Bethel and Jerusalem, in the ninth to seventh centuries BCE. In the 1960s and ’70s, archaeologists excavated two different sites dating from 800 BCE. An inscription to Yahweh and “his Asherah” in Hebrew was found carved in an ancient tomb in the West Bank, near Hebron, then again on two large storage jars in a (possible) shrine in the Sinai Peninsula. Sculptures of the goddess have also been found, including a ceramic carving from the eighth-seventh centuries BCE, and scholars believe Israelite women kept household figures of Asherah for protection.

The Hebrew Bible is rife with text on the goddess and her representations. Most commonly, it refers to “the asherah”—or the plural “asherim”—as a tree, pole, or idol. Scripture condemns her worship as idolatrous and instructs followers: “… take out of the Temple of the Lord all the utensils that were made for the Baal and for the asherah, and for the entire host of heaven” (2 Kings 23:4); “You shall not plant for yourself an asherah, [or] any tree, near the altar of the Lord, your God ...” (Deuteronomy 16:21); “And now, send and gather for me … the prophets of the Baal four hundred and fifty and the prophets of the Asherah four hundred who eat at Jezebel’s table.” (Kings 18:19)

“The very fact that the biblical writers had to spend so much energy condemning this over and over and over means that, for a certain segment of the population at certain periods of time, this was a meaningful, profound, and important part of their religious tradition,” Ackerman said.

So, were our ancient ancestors pagans, and did Tu B’Shevat stem from paganism? It depends on your definition. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines “pagan” as “a person who worships many gods or goddesses or the earth or nature.” In 2 Kings 23:7, the scripture names those who worship Asherah as pagans: “And he demolished the houses devoted to pagan worship that were in the house of the Lord, where the women weave enclosures for the asherah.” Also, considering the Israelites’ adoption of Canaanite deities, like Asherah—as well as scripture surrounding the Golden Calf (Exodus 32:4-5) and Rachel stealing her father’s idols (Genesis 31:19, 32, 34)—it’s safe to assume their polytheism would be pagan. However, Ackerman calls them “henotheistic”: the worship of one god without denying the existence of other gods.

Rabbi Erev Sherman of the Conservative synagogue Sinai Temple in Los Angeles believes there is a distinction between Israelites and Jews, and that Jews were not polytheistic: “We’re not Jews of the Torah, and we’re not Jews of the Bible; we’re Jews of the rabbis. In 800 BCE, we were Israelites of the Bible, not Jews of the rabbis,” he said. “Our ritual practice and religious traditions have evolved.”

For some modern Jews, evolution means looking back to history and a time when the goddess was just as present as God. During the JeWitch Collective’s Tu B’Shevat celebration, members danced, told stories about their ancestors, and made ceremonial offerings—some to Asherah—of dates, figs, and other types of fruit. “I’m sure somebody has put up a shared shrine” of Yahweh and Asherah, Gottlieb said. “I think people like to create Divine images. It’s a way of expressing beauty.”

While Gottlieb doesn’t know whether Tu B’Shevat originated with Asherah, she believes the Israelites could have honored her during all of the festival days. For our modern world, Gottlieb thinks of Asherah as an important symbol for modern-day feminism and activism: “The really positive thing about Asherah is a sense of creating a place of mutual aid where people bring their offerings so that the poor and landless can be fed,” she said. “Another aspect of Asherah is the idea of sharing our bounty and mutual aid as the ground of religion. The best part should not be forgotten.”

Rachel R. Román is a writer and photographer who has written for Forward magazine and Geekwire.com. She has written and taken pictures for the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, The Cholent and Jewish in Seattle magazine.