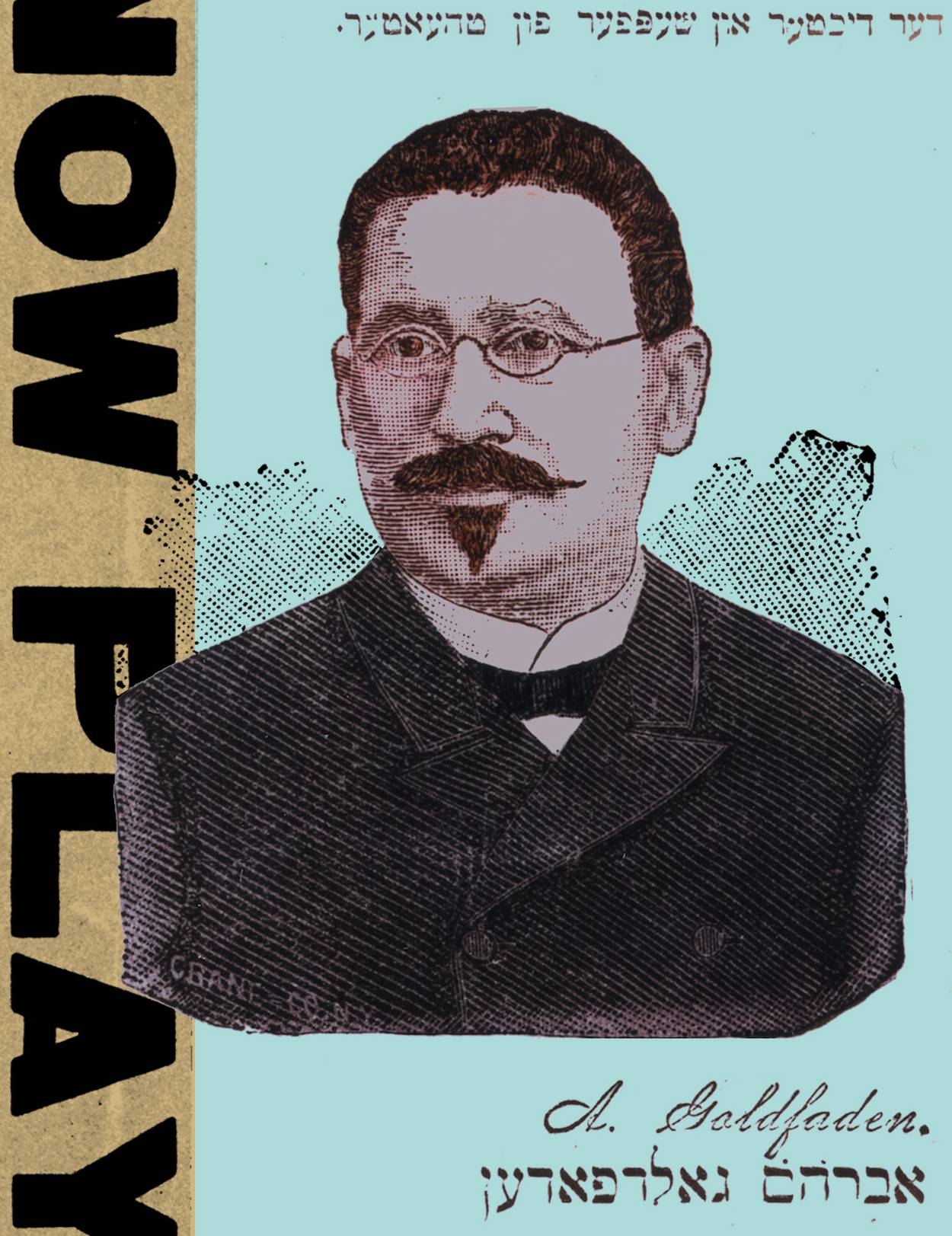

The Accidental Rise of the Modern Yiddish Theater

Its birth owes everything to an unlikely hero, Avrom Goldfaden, and a well-timed war with the Turks

In his memoirs, Jacob Adler described his days as a young adult in Odessa before his discovery of modern Yiddish theater. Adler would eventually become one of the most legendary actors on the Yiddish stage, first in the Russian Empire, then in London, and finally in America. But in his early years, Yiddish theater wasn’t even permitted in Odessa.

Located in the Pale of Settlement, 19th-century Odessa was perched strategically on the Black Sea with an active port that generated significant import/export business. Of approximately 350,000 residents in 1880, Jews comprised 6% of the population, numbering more than the city’s Ukrainians and Poles. It was a rapidly growing multiethnic city, and Odessa’s Jews had a modern sensibility, enjoying a sense of enfranchisement (they were, for instance, permitted to participate in municipal affairs) and, for a relatively large number of them, wealth from vigorous business activity.

Like other ambitious young Jews, Adler spent every free moment attending opera and theater. “I was a dandy with my cape, my top hat, my gloves, attractive neckties, and patent shoes,” he recounts in his memoirs. “Even my walking stick that I bandied about when I walked down the street, sung in my hands.”

He was not alone. Memoirs by other Yiddish performers document their own keen attendance of Russia’s opera houses in their youth, when Yiddish-language theater was strictly banned throughout the Russian Empire. A young Avrom Goldfaden, who probably deserves the most credit for inventing Yiddish theater, and who would eventually compose more than 20 Yiddish operettas performed on prestigious stages throughout the world, wrote in his own memoirs: “I had plenty of opportunity to see the best dramas and operas of that time, Polish, Russian, German, and all the smaller operettas from the most famous of Verdi and Meyerbeer and Halévy (…) and all of Wagner’s works.”

As a sophisticated admirer of European high culture, why would a man like Avrom Goldfaden go out of his way—including the risk of challenging the czar’s legal barriers against Yiddish public performance—to create a new form of theater distinct mostly for its use of the Yiddish language, a language the Jewish intelligentsia itself saw as a vessel of parochialism? In fact, the modern Yiddish theater just barely came into being at all. It was incubated in urbane and multicultural Odessa, to be sure, but it’s rise was set in motion by an accident of history.

Born in Old Constantine (Western Ukraine) in 1840, Goldfaden was the eldest child of a modest and pious clockmaker. To avoid their sons’ conscription to the Russian army, the Goldfadens sent Avrom to a Russian-Jewish gymnasium, one in a network of high schools that were part of the Great Reforms introduced by Czar Alexander II to modernize and integrate its Jewish population. A gifted student with much of the Tanakh memorized by his teenage years, Goldfaden wrote songs and poetry in both Hebrew and Yiddish.

Goldfaden was one of a small group of students to win a scholarship to an exclusive Russian-Jewish seminary in Zhytomyr; there, over the course of seven years, he mingled with the sons of big-city Russian Jews, at least some of them from Odessa. Upon graduation, there was only one city for him. He boarded with a rich uncle and enjoyed Odessa’s cafés and theater life. In 1875, in dire financial straits, Goldfaden left the city to seek more opportunities. He would return three years later as a theater impresario with a bundle of operettas and a fledgling troupe of actors.

Together with a friend, the Yiddish novelist Yitskhok Yoyel Linetski, Goldfaden moved to Lemberg (a city just beyond the Russian border in the Austro-Hungarian Empire), in order to publish a Yiddish newspaper. Like Yiddish public performance, the publication of Yiddish newspapers was also prohibited in Russia, but the men figured they would smuggle copies of the newspaper into the empire for distribution. The effort collapsed after less than a year. But, as the newspaper declined, Goldfaden received a letter from a Romanian Jew named Isaac Librescu, a former subscriber.

In his letter, Librescu invited Goldfaden to visit him in Iași, Romania, where Librescu belonged to a fraternal lodge of progressive-minded Jewish men that sought stronger connections with their more sophisticated Russian counterparts. Hard up for cash, Goldfaden went to Iași and entertained the men with lectures and formal declamations of his poetry. So impressed were they with his presentations that they convinced him to perform his poetry at Shimon Mark’s Café, a tavern that provided small-time Yiddish-language entertainment to its customers. Although embarrassed at the thought of performing in a tavern, Goldfaden agreed.

As he describes in his memoirs, Goldfaden dressed impeccably that night in a tuxedo, bowtie, and gloves, and recited a poem in the formal Russian declamatory style. The crowd promptly booed. Insulted and incensed by what he considered a boorish audience, Goldfaden left the stage. In his place, an entertainer of Yiddish skits and songs named Yisroel Grodner danced onto the stage dressed in Hasidic garb. He sang a song composed by Goldfaden. The crowd loved it.

That evening, Goldfaden and Grodner began a collaboration in which Goldfaden wrote songs and dialogue, and Grodner performed them. From this, they grew into a troupe: First, they recruited Sachar Goldshteyn, a long-lashed saddle-maker with a beautiful voice, well suited to play women’s roles. Goldfaden created the character of a mute bride for Sophie Karp, the first woman performer on a public Jewish stage. Over the following months, they added more performers, mostly former synagogue choristers or folk performers. With each new recruit, Goldfaden’s works became more elaborate.

Previous historians have seized on Goldfaden’s memoirs about these months in 1876 as proof that Yiddish theater began with Goldfaden channeling the performance practices of small-bit entertainers who learned their craft in shtetls as wedding jesters and purim shpilers. The historian Jacob Shatzky, for instance, takes the impresario’s contempt for his rough-hewn actors as evidence of the theater’s authentic folk roots. “Goldfaden wanted to create a theater like other national theaters. But other nations had variegated audiences that satisfied their tastes each according to their education. At that time, however, the Yiddish theater had only one type of audience member—the common Jew, the worker, [and] the storekeeper.” For Shatzky, Goldfaden’s use of this folk element, however reluctant, helped define the new genre.

Still, Goldfaden quit the troupe after less than a year. Iași’s Jewish population was not large or moneyed enough to support the launch of the kind of theater to which he aspired in class, and taste. He had envisioned mounting his work in Odessa’s Mariinsky Theatre, but it was impossible to make the productions grand enough or sophisticated enough. He could not raise ticket prices and, therefore, he could not expand his troupe beyond a handful of ragtag actors. Without more money, Goldfaden was stuck at Shimon Mark’s Café with its mostly working-class audience. In late 1876, he washed his hands of Yiddish theater. He even considered medical school.

But then, an accident of history occurred: The mountain came to Muhammad, or, rather, Odessa came to Iași. Revolutionary activities against the ruling Ottoman Empire began brewing in some of its principalities, including Bulgaria, Serbia, and Romania, which convinced Russia that the time was ripe to curtail the Ottoman’s European presence. Russia declared war on the Ottomans in April 1877, initiating the bloody, two-year, Russo-Turkish War. Romania, sandwiched between the two empires, welcomed Russian troops to its territory to attack the Turks and assembled its own army to fight alongside the Russians. With this war, Romania achieved its political independence. It also saw the population of its cities skyrocket temporarily with the presence of Russian troops.

Not far behind the soldiers—to service their needs, including food and drink—came Russian contractors, many of them Jewish merchants, and many of them from Odessa, including a good number of merchants personally acquainted with Goldfaden. It was as if Goldfaden’s ideal audience—Jewish, sophisticated, theater-going, and with disposable income—had been lifted from Odessa and placed in Iași, beyond Russia’s ban on Yiddish public performance. Suddenly, Yiddish theater seemed like a good idea again.

For the two years of the Russo-Turkish War, Iași wasn’t really Iași. It was more like Odessa. By the time the war ended a year later in 1878, Goldfaden’s troupe had absorbed many educated Russian-Jewish performers, played the largest venues in various Romanian cities, and had performed for rich merchants and high-ranking Russian and Romanian officials, whom Goldfaden honored with ritualized greetings and preferential seating. With this new network of military and government connections, Goldfaden was able to travel to St. Petersburg to request permission to stage Yiddish-language productions throughout the empire. When the war ended in 1878, Goldfaden’s troupe was on a fast train to Odessa.

Yiddish theater turned out to be a natural part of the 19th-century Russian performing arts scene, which was passionately embraced by many of its cities’ multiethnic populations, especially its Jewish residents. Odessa epitomized this trend. One of Goldfaden’s friends, the fiction writer Nahum Shaikevitsh, attended Goldfaden’s shows and noted that the enthusiasm Odessa Jews already felt for the theater was magnified and channeled toward the Yiddish theater. “One who has never seen the passion in play has no conception of what ‘visiting the theater’ meant,” Shaikevitsh writes in his memoirs: “All the seats were sold out three nights before every show ... the applause and bravos were deafening.” Assimilated Jews who had long spoken their last words of Yiddish were surprisingly but utterly enthralled.

Most seats at most Yiddish productions staged in city opera houses during this period, however, were filled by non-Jews. How can this be? Yiddish theater benefited from the wide-ranging tastes of non-Jewish Russian theatergoers, which had long included a diet of works in foreign languages. The Yiddish language was as incomprehensible as German or Italian to most Russian theatergoers. Moreover, the ethnic elements of Goldfaden’s theatrical productions, whether it was the hapless Hasid or the judicious modern Jew, played to the expectations of Russia’s theater audiences. In January 1880, Goldfaden negotiated a contract to stage Yiddish operetta at Odessa’s majestic Mariinsky Theatre twice a week. After only five years, he had finally arrived.

And then there is the more intangible reason for turning to Yiddish theater, a reason which resides in the value of creating culture in one’s own vernacular: in shoring up the familiar cultural references and idioms of one’s world and wedding these idioms to the structures of a new and contemporary language of performance.

Remarkably, Goldfaden’s troupe, and those of his competitors, were part of a growing number of commercial theaters making inroads in the Russian Empire. They performed in St. Petersburg and Moscow, but, on the whole, Yiddish troupes pursued relatively newer Jewish settlements in cities like Odessa, Kiev, Kharkhov, and Nikolaev, reflecting the growing presence of Russia’s business elite as investors in cultural life.

This picture of the Yiddish theater’s urban roots is mostly absent from the traditional narrative about the rise of the modern Yiddish theater. It challenges the dominance of the shtetl origins of the theater, and suggests that elite venues and Jewish and non-Jewish urban-based audiences were the true incubating force. The city is certainly the key to the cultural momentum that the Yiddish theater drew upon after 1883, when Czar Alexander III reinstated the ban on public Yiddish performance. By this point, there were already about 100 Yiddish actors, all part of a thriving artistic enterprise—as fragile as it was—made up of a corpus of operettas they all knew by heart. They had relationships to each other and their audience. Despite the renewed ban, they weren’t going back to jobs in factories or working for their fathers. By 1883, there was something called “Yiddish theater” and it was not going to go away. Instead, its practitioners loaded it into suitcases and transported it halfway across the globe, to the goldene medina.

Had there been no five-year suspension of the ban spearheaded by Goldfaden, there would likely not have been such a thing as the modern Yiddish theater, especially not the coherent institution we have come to know. This is not to suggest that there would be no Tin Pan Alley or Broadway or even Fiddler on the Roof, (which Sheldon Harnick and Joseph Stein drew from Sholem Aleichem’s novel, and not its iddish dramatizations). Yiddish theater was not a direct stepping stone to any of these. However, there might not have been the many dozens of crossover writer-actors like Paul Muni or Molly Picon, and, for that matter, no Sidney Lumet or Stella Adler, who were shaped profoundly by their or their parents’ experiences on the Yiddish stage. The Hebrew theater Habimah would not have been born so early (in 1920 in Russia) without the preexistence of Yiddish theater. There would be no God of Vengeance, no Dybbuk or Mississippi or any number of great—yes, truly great—works that still await discovery beyond Yiddish audiences, because they were of, and for, the Yiddish stage that mostly is no more. And there would be no Solomon Mikhoels, Maurice Schwartz, or Ida Kaminska, or countless other innovative interpreters of the stage.

Observers might point to the phenomenal run of the Yiddish theater in New York City and argue that if the Yiddish theater had not started in Russia, it would have inevitably launched in the United States. Didn’t America blend the requisite freedom of Romania and the entrepreneurialism of Odessa? Indeed, the Yiddish theater flourished in New York City, benefiting from its dense population of Jewish immigrants living within walking distance from dedicated theaters. But the evidence suggests that, as effective as New York was in accepting and growing the transplanted actors and works of the Yiddish theater, it did not have the ingredients to nurture it on a grassroots level. Well before becoming a matinee idol, a young Boris Thomashefsky attempted to stage a Goldfaden operetta in 1882 after hearing about the Yiddish theater’s successes in Russia but he gave up after a few shows. New York City’s Yiddish-speaking population was less sophisticated, they were Russia’s poor and huddled masses raised in shtetls, not cities. Moreover, Yiddish theater led a relatively ghettoized life in New York. It was not that it failed to appeal to non-Yiddish theatergoers; it was that it didn’t even try.

Thomashefsky’s failure reminds us of the complexity and fragility of the institution of theater, a reminder that is particularly resonant as we consider the catastrophe this pandemic has visited on theaters throughout the world. So much needs to be going right simply for theater not to fail. At the very least, it needs a troupe, a venue, an audience, and a good measure of freedom. In this respect, the experience of the Yiddish theater in Russia is truly extraordinary: It consisted of independent troupes—the Russian newspapers referred to them as “entrepreneurs”— that competed with mostly government-subsidized operetta companies. They were forced to contend with censorship bureaus, finicky local officials, and a wave of pogroms. After each crisis, a troupe leader smoked a cigarette, pawned a costume, and started over.

It is no coincidence that the Yiddish theater on American soil gathered institutional heft in 1885. Consider the timeline. The ban against Yiddish theater was reinstated in Russia in the fall of 1883. For a short time, Yiddish actors waited in Russia as Goldfaden traveled to St. Petersburg to reverse the ban. This time, Goldfaden could do nothing to prevail upon government officials. When his actors grew hungry, they decided they were Yiddish actors above and beyond anything else, and they packed their bags and left Russia. First, they hit London, but by 1885, they reached New York City.

Still, why did a remarkable number of Odessa sophisticates and fluent Russian speakers, men like Jacob Adler, even bother to join the Yiddish theater? Adler’s copious memoirs do not address this issue; their very premise is that he was born for the stage. On a more mundane level, the Yiddish theater was likely the only opportunity for a Jew—no matter how culturally assimilated—to become an actor. The Russian conservatories were closed to “outsiders.” Some Italian and French operetta troupes were open to Jewish performers, but at least some demanded conversion to Christianity. If you were a Jewish performer, Yiddish theater—a long shot, to be sure—was your best hope for celebrity and a life onstage.

And then there is the more intangible reason for turning to Yiddish theater, a reason which resides in the value of creating culture in one’s own vernacular: in shoring up the familiar cultural references and idioms of one’s world and wedding these idioms to the structures of a new and contemporary language of performance. The future actor Isaac Loewy best captures this in his memoirs, penned in 1908. He reports that when he was a young boy, his Hasidic parents considered the theater “treyf”—“for Gentiles and sinners.” Nonetheless, he explained, he was so drawn to theater that he would regularly attend non-Jewish performances in Warsaw’s Grand Theatre. Later, Loewy discovered theater in the Yiddish language:

That completely transformed me. Even before the play began, I felt quite different from the way I felt among “them” [i.e. the Gentiles]. Above all, there were no gentlemen in evening dress, no ladies in low-cut gowns, no Polish, no Russian, only Jews of every kind, in caftans, in suits, women and girls dressed in the Western way. And everyone talked loudly and carelessly in our mother tongue, nobody particularly noticed me in my long caftan, and I did not need to be ashamed at all.

As he describes it, Loewy experienced his first evening with Yiddish theater as the shock of the familiar. He had already known sacred performance and mainstream theater. In the Yiddish theater, however, Loewy experienced the intimacy of his native language and clothing blended with the less familiar social setting of comingling men and women in a secular theater house.

The movement of writers, playwrights, and actors has generally been a move away from their mother tongue of Yiddish toward a larger cultural world, be it Polish, Russian, etc. There is also, however, a throughline in 19th- and 20th-century Jewish history of a desire on the part of various cultural producers throughout Eastern Europe to create Yiddish-language versions of what they read or what they saw in the theaters. That is, to go beyond the borders of Yiddish culture and then to return to creative lives in Yiddish. In these efforts lies the not-so-accidental part of the rise of the modern Yiddish theater.

Alyssa Quint is associate editor at Tablet Magazine and author of The Rise of the Modern Yiddish Theater.