Radar Boys

My dad and the technology that quietly won WWII

Courtesy the author

Courtesy the author

Courtesy the author

On a rainy day in New York City in April 1945, a celebrated fire captain died in Brooklyn, Babe Ruth retired from refereeing wrestling in the Bronx, and a lanky Jewish boy from the Lower East Side was about to turn 18.

Within hours, that boy—a bookish whiz kid and first-generation American Jew, who by then already had two years of college science classes under his belt—walked up Madison Avenue to an otherwise nondescript office building. The war was still raging in the Pacific, and the Draft Board would determine his fate.

But that lanky Jewish boy—my father, Murray Oratz—had other ideas. He’d heard from his neighborhood buddies, students at Bronx High School of Science, about an alternate route: an exclusive Navy science training initiative called, mysteriously, “The Eddy Program.” If he excelled, the guys said, he just might survive the war.

Intrigued, Murray convinced my grandfather Sam, a 1920 émigré from Poland, to accompany him to the Navy Recruitment Center in Midtown. Since Murray was still underage, he’d need Sam’s permission to enlist. After completing the paperwork and applying to take the “Eddy Test,” they went for a coffee at the nearby Horn & Hardart automat. It was the only time Murray saw his father cry. On the day before his 18th birthday, my father entered active duty and boarded a train for Great Lakes Naval Training Center outside of Chicago.

It has been said that the atom bomb ended the war, but in reality, radar won the war.

Radar—an acronym for “radio detection and ranging”—was born in 1897, when Guglielmo Marconi, an Italian electrical engineer, invented a device that could transmit radio signals across three-quarters of a mile. During WWI, radio messaging changed the way armies communicated with their field forces. The postwar period inaugurated the era of giant radio conglomerates—General Electric, RCA, Westinghouse, Western Electric—electrifying America’s households with music and entertainment. Soon thereafter, the Naval Research Laboratory launched investigations on how to use radio waves to detect objects on the ground, in the sea, and in the air.

Radar became a key military research focus for both the U.S. and Great Britain. The first operational American set, installed on the USS New York in January 1939, detected ships at 10 miles out and aircraft at 48 miles. When England declared war on Germany, it was immediately evident that they would need access to the extensive resources and know-how of American engineering and science. The Tizard Mission, a select envoy of British scientists, was sent to disclose everything concerning top secret weapons with their American counterparts. Quickly, the Americans agreed to share their technology.

In June 1940, the National Defense Research Committee was established, acknowledging that this war would be a highly technical struggle—perhaps more than ever before. A new facility for radar research was built at MIT and given the same name as the nuclear research facility at Berkeley, California: the Rad Lab. These labs were critically focused on technologies involving radiation and radio waves. At MIT, the team worked aggressively to enhance the capabilities of radar. In Berkeley and at Los Alamos, the task was to develop nuclear weapons.

Courtesy the author

Eighteen months later, with the surprise Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Navy had only 400 ships and 150,000 personnel. The ambush killed more than 2,000 Americans, wounded more than 1,000, damaged 21 ships, and destroyed more than 180 aircraft. Within days we were at war not only against Japan, but also Germany and Italy. In the scramble that followed, the Navy emergently expanded its fleet to 2,000 vessels—each equipped with radar—and 500,000 personnel. Before then, only 79 radar sets had been installed on Navy ships. The race to develop, build, and install radio electronics was on.

An impending crisis followed on the heels of the radar installation boom: Who the heck was going to operate, and maintain, the instruments? Having radar on board was one thing. Having it ready at all times in perfect working order was another. The solution? William Eddy, a Navy lieutenant retired for hearing loss in 1934, who went on to become a major player in the private sector development of radio and television. The day after the Pearl Harbor attack, Eddy took the overnight train to Washington, D.C. He sought out a senior naval officer in the Bureau of Navigation and pitched his plan: “You’ll need lots of radar men. We can train ’em. We’ve got room, equipment, skilled personnel—you can have it all!” Eddy was immediately enlisted to head up a four-man team to work out the logistics of the Naval Electronics Training Program—the Eddy Program. The squad’s charge was to train radio technicians with the intellectual and practical know-how to innovate, repair, perform preventive maintenance, and keep up with new developments in the technology. To test potential applicants’ mettle, they devised an assessment to screen applicant recruits.

This was the Eddy Test that my father Murray took.

In June 1942, after U.S. forces devastated a superior attacking Japanese fleet, many international onlookers asked themselves the same question: How did they do it? The Americans had destroyed 300 Japanese airplanes and four carriers, while losing only 100 U.S. planes and a single carrier—an incomprehensible victory. That clash—the Battle of Midway— was a turning point in the war for the Allies. Radar, the U.S.’ secret weapon, proved the importance of maintaining every technical advantage.

Four years later, Murray Oratz was sent to Great Lakes Naval Training Center for Navy basic training.

“When I got to Great Lakes, it was boot camp,” my father told me. They tied ropes and knots; shot handguns and rifles; rowed boats and bailed out water; and leaped off 10-foot diving boards. It all put shooting air-guns for stuffed bunny rabbits at the Coney Island Amusement Park in another context.

Having completed the preliminaries, Murray and his group moved on to Pre-Radio. For the next four weeks they would be based at Wilbur Wright Junior College in Chicago.

“The company I was in were kids from New York,” my father told me, adding that “there were a few Jews there with me,” including a Perlmutter and a Parsons. Their days centered on classroom learning—mathematics, physics, electricity, magnetism; a giant demonstration slide rule was mounted across the top of the blackboard for carrying out computations at lightning speed. Outside the lecture hall, they soldered and drilled in the lab. Classes started at 7:30 a.m. and ran until 5 p.m., with post-dinner “problem-solving sessions,” then homework and finally sleep. As members of this special radar unit, their Navy uniform badge was embroidered with four electrical spark bolts.

Each week had high stakes. Every Saturday morning would include an exam, my father told me. “If you didn’t pass the exam ... you were shipped out to the Pacific.”

“Bang, bang, bang.”

Primary School came after Pre-Radio. Murray left Chicago for the Gulfport Naval Training Center in Mississippi, the least desirable location of all the Primary Schools scattered around the country. The next 12 weeks, the summer of 1945, would be spent in what Murray recalls as “a hellhole.” A swampy heat enveloped them; malaria-ridden mosquitoes terrorized them; palmetto bugs crawled all over and especially inhabited their socks. A nearby POW camp for a particularly notorious group of Nazis—those serving under Erwin Rommel, better known as the “Desert Fox”—had better living quarters than the Navy guys.

“If your son is overseas in the war, send him socks, chocolate, and cigarettes,” my father recalled Walter Winchell, the radio commentator and syndicated columnist, advising mothers. “If he is in Gulfport, Mississippi—pray for him.”

Instructors did not take any pity on the recruits when it came to academics, either. “The days were long,” my father told me, “two hours lecture, two hours practical, lunch, two hours lecture, two hours practical, dinner, homework. Sleep. Repeat.”

Weekend leave started as soon as the Saturday morning test was completed. There was nothing going on in Gulfport, so the boys would head for the bus to Biloxi, the nearest town, or the train to New Orleans. They’d go swimming in Lake Ponchartrain, eat Cajun food, listen to jazz, and sometimes—Jews and all—catch a nap in a local YMCA, where they were sure to keep their wallets under their pillows.

In August 1945, the U.S. dropped the atom bombs on Japan. “The war is over,” Murray and his peers realized. Yet, for them, training and active duty continued. Soon, they were headed back up north for the next stage of the program: Secondary School. Months later, Murray graduated in class 10-46 with a new badge on his uniform: electrons orbiting the atom.

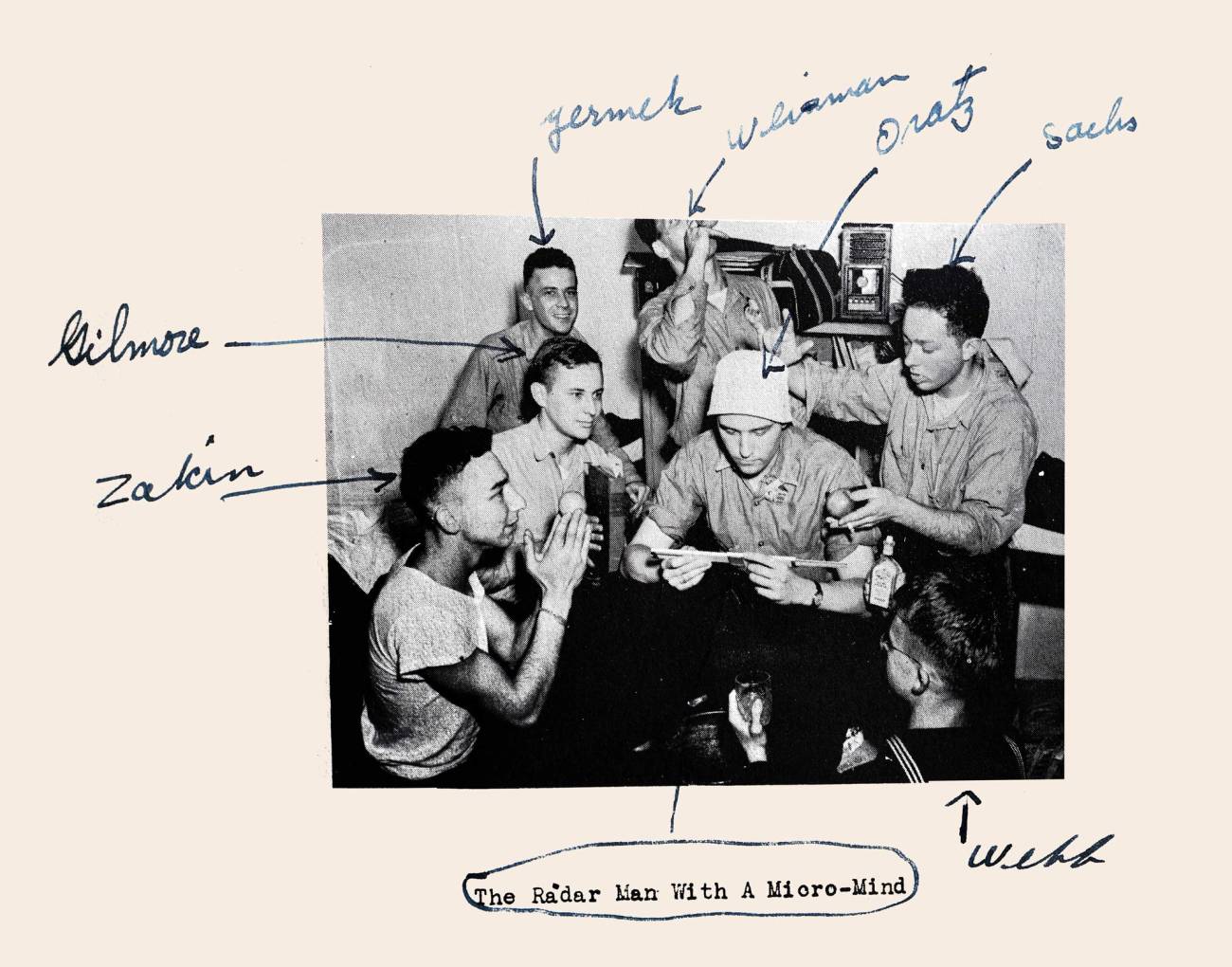

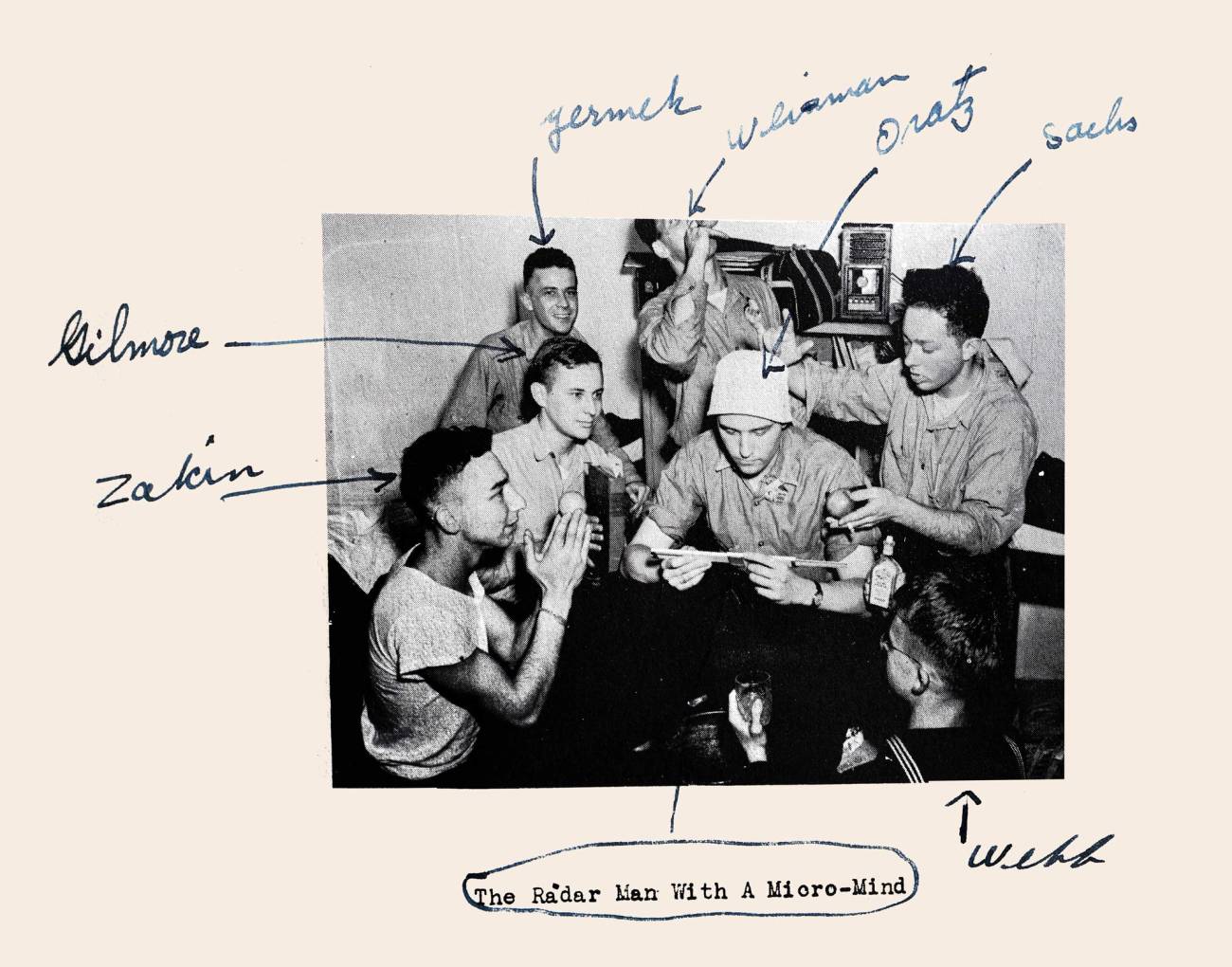

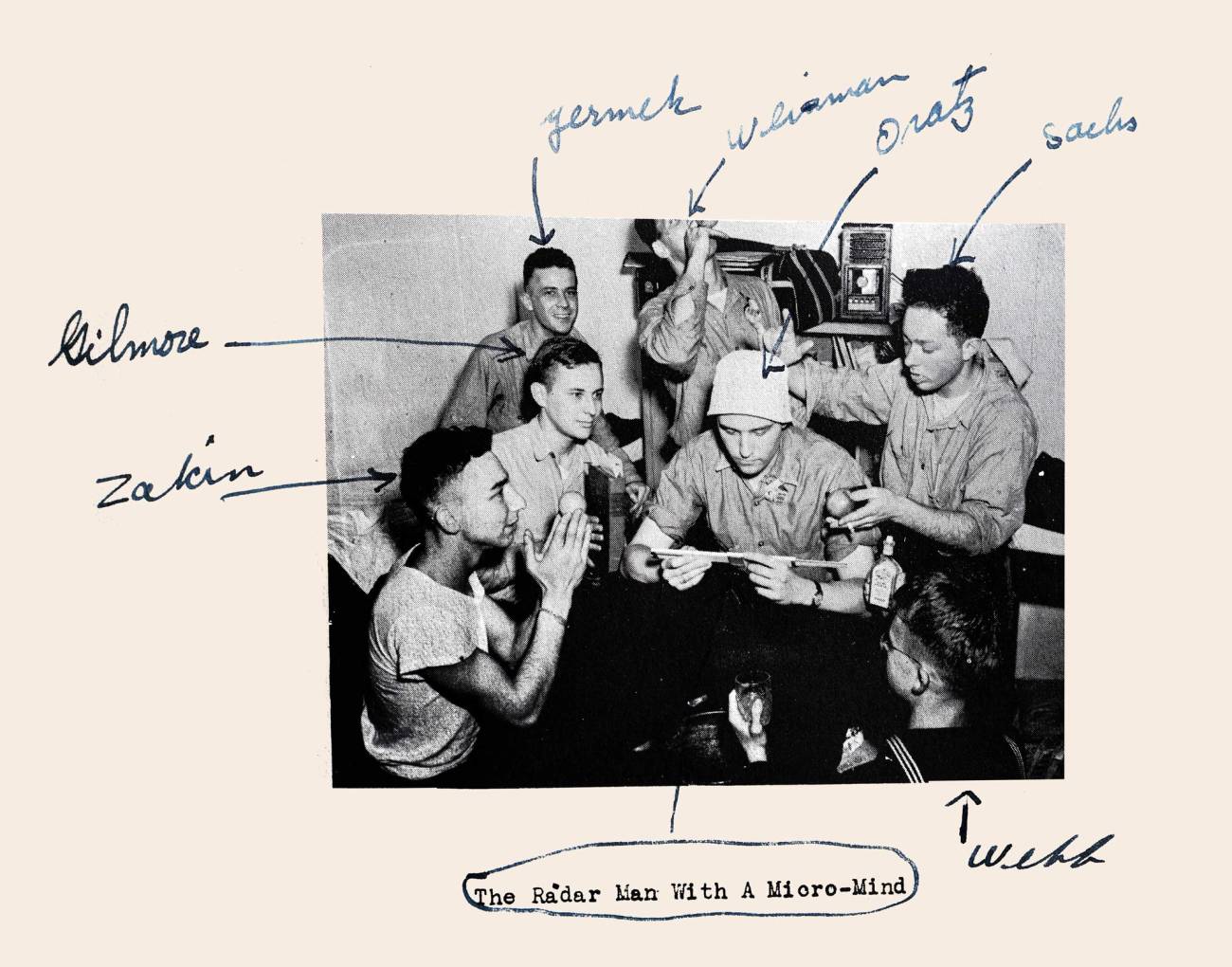

Among the graduates were “a lot of New York Jewish guys,” my father told me: “Allman, Cohen, Frankfurt, Freeland, Gold, Goodman, Heller, Kahn, Kestenbaum, Nemeovsky, Nussbaum, Parsons, Perlman, Pollack, Sachs, Weiman, Yermak, Zakin.”

“And me, Oratz.”

Oratz, Perlman, Nussbaum, Parsons, and another guy who scrubbed his face so he wouldn’t get pimples were lying on a grassy slope, absorbing a warm and sunny day in D.C., when they first spotted the ship coming up the Potomac. It was a big, ugly behemoth—one easily mistaken for a WWI ship or a Coast Guard vessel—until they noticed the guns, the pennants, and the blue flag with white stars. It was the USS Pocono, the flagship of the Atlantic fleet.

A few days later, Murray and a couple of his pals packed their lives into the Navy-designated sea roll and hauled themselves aboard.

The USS Pocono was an amphibious force command ship loaded with the most advanced electronics, communications, and extensive combat information spaces available. And the ship’s exhausting standards extended to the smallest pieces of daily life: the way you saluted, the way you responded to roll call, and the way you wore your cap.

ETM First Class Oratz, ID number 7164718, was on the waves.

Courtesy the author

Murray was assigned to Radio 2—a unit that sat high up on the ship, manning what he called “the big transmitters … which could transmit all the way to the end of the world.”

A couple of weeks in, mid-snooze between shifts, Murray was shaken awake. A man he’d never met told him, “They are calling for you from the Admiral’s Deck.”

And off my father went—up a ladder, into the Admiral’s Quarters—to find a Marine. “I think I broke the Admiral’s radio,” the Marine told him. He walked over to the instrument and, “Gut in himmel,” Murray recalls thinking in Yiddish, “it had a million dials … I couldn’t find the on/off switch. … I have no idea what I’m looking at.”

But, soon enough, my father hit his stride. He turned the dials—London talk radio, then Chicago jazz, then D.C. local news—and, eventually, the Marine came back inside.

“You have faith?” Murray asked the Marine.

“What?”

“Moment of truth,” Murray replied.

Then: music.

Murray served on the USS Pocono until August 1946. The war was over. His last day on the ship, that big, ugly, iconic, history-altering monster pulled into Lido Beach, Long Island. My father was honorably discharged with two subway tokens. He used them for the ride home to his parents on the Lower East Side.

In the time since Murray returned home, radar and radio have transformed day-to-day life in America and around the world. We watch television, listen to the radio, work on computers linked to the internet, cook in microwave ovens, depend on satellite radio for GPS directions, operate remote controls and cellphones, and depend on air traffic control to travel safely. Military applications, likewise, remain vital for communications, detection of enemy forces, encryption devices, and operation of drones.

After the war, Murray completed his education on the GI Bill with a Ph.D. in biochemistry, later running the Nuclear Medicine department at the Manhattan V.A. Hospital—in some ways a civilian equivalent of the Rad Lab. The Eddy Test won the war. It also definitely changed the life of a Jew from the Lower East Side. Maybe, it even saved his.

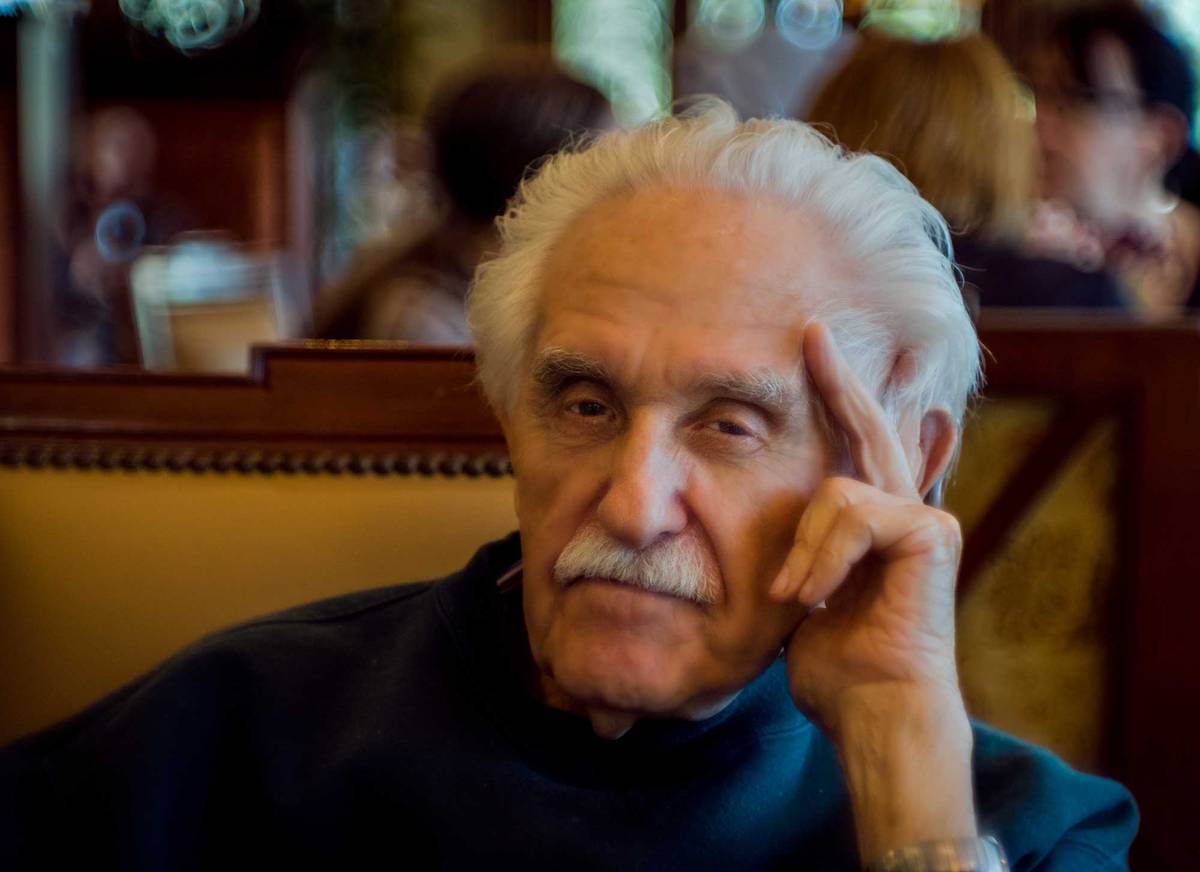

Today, my 96-year-old dad still has the best radio, computer, and media sound systems of anyone I know. These days, though, it’s for personal use: streaming music, like that day with the Marine on the USS Pocono—and also watching videos of his new great-grandson learning how to walk.

I guess he’s still a radar boy at heart.

Ruth Oratz is a Professor of Medicine at NYU Langone Medical Center.