A People and Its Parchments

A new exhibit examines the Holocaust through the experience of scrolls

In the Purim eves of his childhood, Herman Jakubowicz would watch his grandfather stride into shul—where the congregants waited, expectant—with a scroll tucked under his arm, heralding the transition from a day of fasting to a night of merrymaking. Theirs was the only megillah in Brod, a hamlet in the sub-Carpathian foothills of what was then Czechoslovakia and is now Ukraine. A third of the townspeople were Jews. Some were loggers and farmers; others owned flour mills, workshops, even a distillery.

Born in 1921 to Fanny and Leopold Jakubowicz, Herman was the eldest of five in an observant family. Life was good for Brod’s Jews so long as the Czech ruled. They were tolerant and obliging, even running extra trains on Fridays to accommodate pre-Sabbath travel. But Brod slipped into Hungarian control in 1939, bringing anti-Jewish restrictions, and by 1941 dozens of Jewish men, Herman among them, had been conscripted into Hungarian labor battalions. Circumstances grew worse when Herman’s labor camp fell into German hands.

But by September 1944, Russian artillery fire was audible. With nothing to lose, Herman and two friends escaped into the forest the day after Yom Kippur. Friendly Russian soldiers guided them away from the front—and within months, the war was over.

Herman headed home, but the Brod he knew had vanished. His father and mother? Gone. His siblings? Gone—to Auschwitz. (One, Jakob, survived.) Gone also were the rest of the 400 or so Jews who had lived in Brod in 1941.

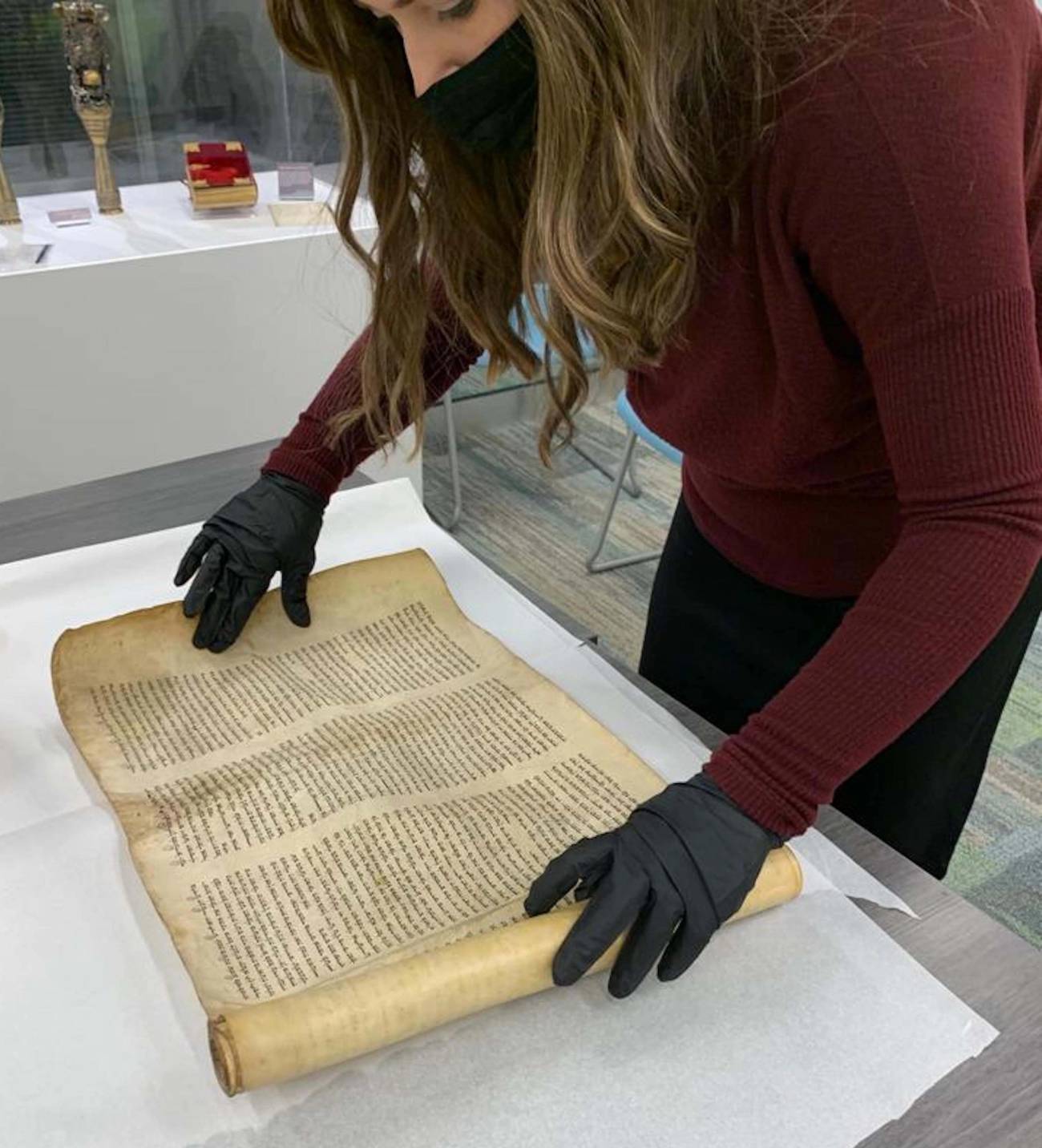

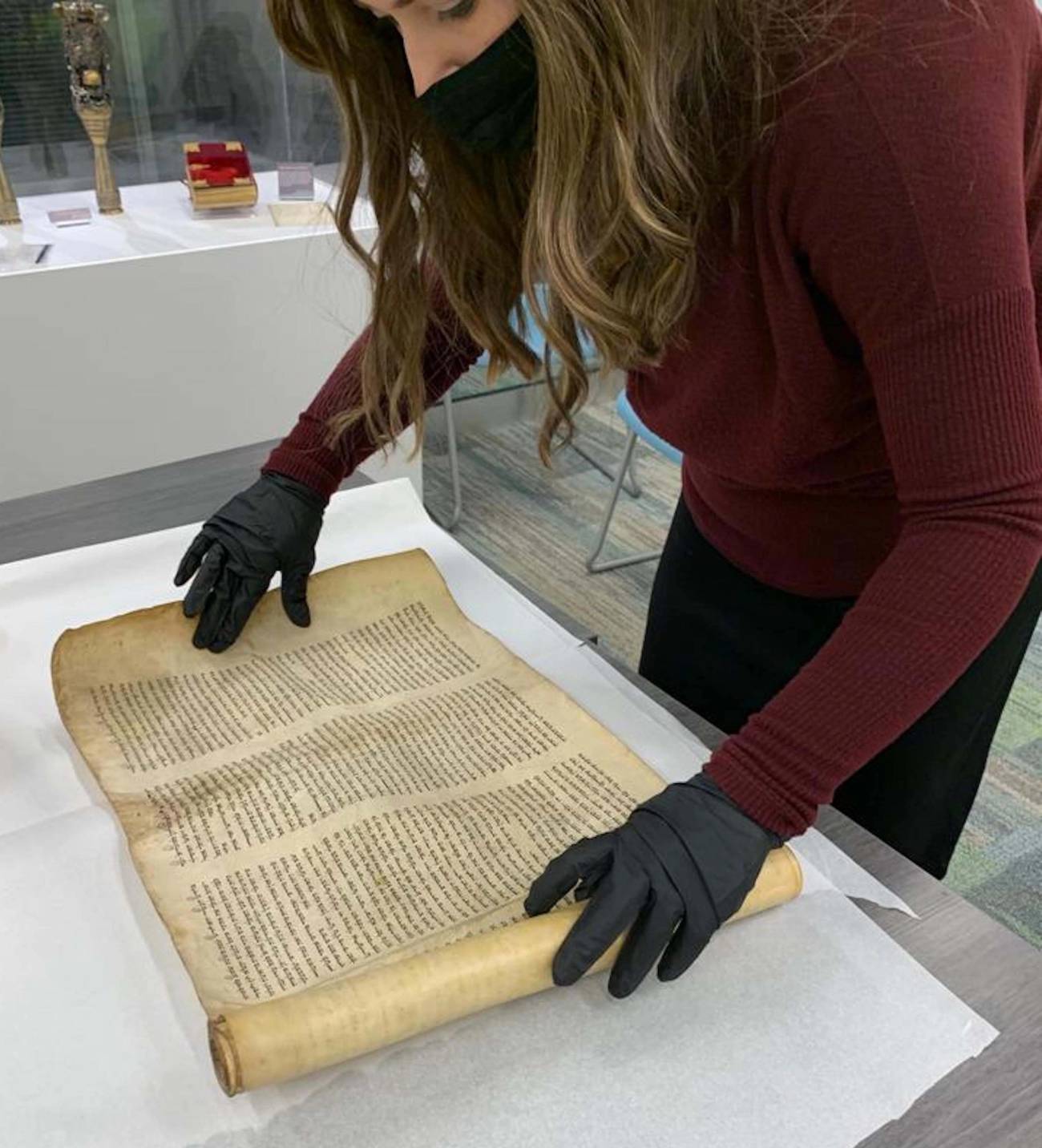

The Jakubowicz home stood vacant, everything of worth seemingly taken. But Herman knew that Leopold had kept valuables in an attic crawl space. So up he went, his hunch rewarded with a revelatory find: the family megillah, amid a cache of other items, wrapped in cloth. It was easy to imagine his father hiding this treasure as best he could in the frenzied days before deportation.

This scroll, of course, told of an averted genocide—the dramatic tale of Esther, Mordecai, and Haman in the fifth century BCE—removed from Herman by thousands of miles and years. And it had survived another genocide, this one nearly successful, on lands his family knew intimately, in a past so recent his body and psyche still bore its marks.

After two years in Munich gaining education in clothing design, Herman found his way to America, bringing the megillah with him. He rebuilt his life in this country, a tale common to so many survivors yet unique to each. In Herman’s case, he married a widowed survivor, had a son, settled in Queens, and became a successful manufacturer of women’s outerwear, speaking often to his family of the megillah that linked him to a world lost. Several years before his death in 2000, Herman gave the scroll to his son, Len Jacobs, to safekeep.

“It was the safest place I could think of,” said Len Jacobs, his voice breaking as he explained the decision he and his wife, Genee, made to donate the megillah to the Holocaust Museum & Center for Tolerance and Education (HMCTE) in Suffern, New York, in 2016.

HMCTE is in Rockland County, which has the highest concentration of Jews among U.S. counties with a population of more than 10,000. The institution’s origins trace to the 1980s, when a group of survivors, determined to transmit their stories to future generations, met on the Rockland Community College campus. “A library provided space,” said Andrea Winograd, current executive director of the museum, now located on the campus. “Designers, construction workers, electricians—many of them survivors—donated their time to the project.”

And then artifacts began trickling in, items quotidian (a liberator’s hat) and sacred (a pair of tefillin). Sometimes objects were left anonymously at the museum’s stoop, history unknown and provenance left for museum staffers to research.

Over time, HMCTE grew into a thriving regional educational institution. More than 10,000 people, including many students, visit each year. And the museum actively collaborates with local minority communities, producing programming around tolerance and moral courage.

Sacred Scrolls of the Holocaust, which centers around the Jacobs family’s relic, is the newest exhibit at HMCTE. Also on display are other items from the museum’s collection—a siddur, tefillin, etc.—united by a shared identity: scrolls spared from an inferno.

The Holocaust experience of scrolls in many ways parallels the experience of Jews. Both genres of victim were gathered, cataloged, violated, abused, and destroyed.

The two phases of the megillah’s story—its pre-Holocaust origins and post-Holocaust discovery—are bisected by a review of the experience of scrolls in general during the war. “We saw the megillah as a portal for exploration of this larger topic,” said Julie Golding, curator of the installation. To her mind, it’s a narrative seldom relayed.

In the public consciousness, after all, what is the Holocaust? A series of freighted names (Auschwitz, Dachau, Treblinka), a single number (6 million), and countless black-and-white photos of terrorized Jews. The Holocaust is a concentration camp the way the French Revolution is a guillotine: cataclysms flattened into neat imagery for easy mental storage. But such reductionism is dangerous for the level of detail—profound and banal—it often elides.

Sacred Scrolls of the Holocaust, in contrast, pushes visitors to confront aspects of the well-chronicled attempt at genocide glossed over in broadstroked tellings. Its reveals how the Nazis sought to destroy not just Jews, but Judaism; not just a people, but their defining artifacts and traditions. According to Elisabeth Hope Murray, president of the International Network of Genocide Scholars, “cultural death is at the heart of the genocidal process.”

The term “genocide” was coined by the Polish Jewish lawyer and activist Raphael Lemkin in 1944. “In defining it, he described two elements,” said Kerry Whigham, co-director of the Institute for Genocide and Mass Atrocity Prevention at Binghamton University. “The first is barbarism, or physical destruction. The second is vandalism, the destruction of the cultural underpinnings of the group.”

In fact, culture is often assaulted early in genocidal progressions, its destruction serving as an indicator of a radicalizing regime. The ravaging of Judaica on Kristallnacht is one example.

Michael Berenbaum, a scholar who consulted for Sacred Scrolls of the Holocaust, noted a possible root of the Nazi drive to destroy Jewish culture. “The Hitlerian creed of a master race rested on the idea of the survival of the fittest,” he explained. “The Nazis believed the supreme Aryan race would outlast all others.”

This Darwinian vision is antithetical to notions of justice and compassion, which are central to Jewish traditions. To assure Aryan supremacy, Berenbaum theorized, the Nazis needed to attack not just Jews but also Judaism, whose teachings ran counter to a strongest-group-wins ideology.

Thus the Nazi campaign of deliberate and comprehensive desecration: burning Torah scrolls, using synagogues as stables, converting gravestones into pavement, repurposing hallowed parchment into shoes and drum skins.

As stage-setting, the HMCTE exhibit highlights Judaism’s veneration of scrolls by noting, for instance, how Jewish law requires 40 days of communal fasting should a Torah be dropped. This helps explain why Nazi defilement of Jewish scrolls so chilled onlookers. One panel quotes survivor Sigmund Tobias’ recollection of smoldering Torahs: “I will never forget how terror struck this 6-year-old at the realization that there was no safety for us anywhere.”

Not quoted was Heinrich Heine’s prescience. “Where they burn books, they will, in the end, burn human beings, too,” the German poet wrote in 1822.

It’s difficult to experience Sacred Scrolls of the Holocaust without considering the relationship between people and their things. The psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi identified two distinct kinds of materialism. “Terminal materialism” is the desire for something for the sake of having it. “Instrumental materialism” refers to wanting a thing that is “a bridge to another person or to another feeling.”

Objects of religious import—menorahs, rosary beads, prayer rugs—fall in that latter category. Judaism especially is rife with ritual objects: shofars, etrog boxes, dreidels, Seder plates, kiddush cups, spice boxes, handwashing vessels, tefillin, tallitot, charity boxes. And of course, all the books.

These items are valued because they connect their owners to divinity and, as often as not, to ancestors: Bubbe’s candlesticks, Zayde’s Haggadah, Mom and Dad’s mezuzah. We kiss Torahs; we store tefillin in embroidered bags; we stack books deliberately, holiest on top. Thus, in part, the anguish, easily recollected decades later, from seeing siddurim torn, tefillin crushed, Torahs burned.

The Holocaust experience of scrolls in many ways parallels the experience of Jews. Both genres of victim were gathered, cataloged, violated, abused, and destroyed. And there are similarities in their aftermaths, too: the rewriting and rededication of Torahs, the recreation of families and communities.

All this is carefully rendered in HMCTE’s exhibit, which opened, pointedly, in the days preceding Tisha B’Av, a day of mourning commemorating the destruction of both Jewish Temples in Jerusalem. Emphasized throughout is the way Jews cherished religious writings in their most harrowing hours: hiding them in bunkers and cemeteries, taking them on train rides into the unknown. That, ultimately, is the thrust of the exhibit: the deep connection between a people and its parchments. It’s about seeing the victims before they were victimized, as individuals with beliefs and with things. It’s about cultural devastation, and the remnants that survive, and the traditions that carry on.

As for the scroll that centers the exhibit, its letters still gleam impressively black. Its words tell one tale of survival. It tells another just by being there to be seen.

Hannah Rubin is a writer and content producer at the editorial consultancy Elland Road Partners.