Learning—and Teaching—Yiddish

Poetry and music to start the new year

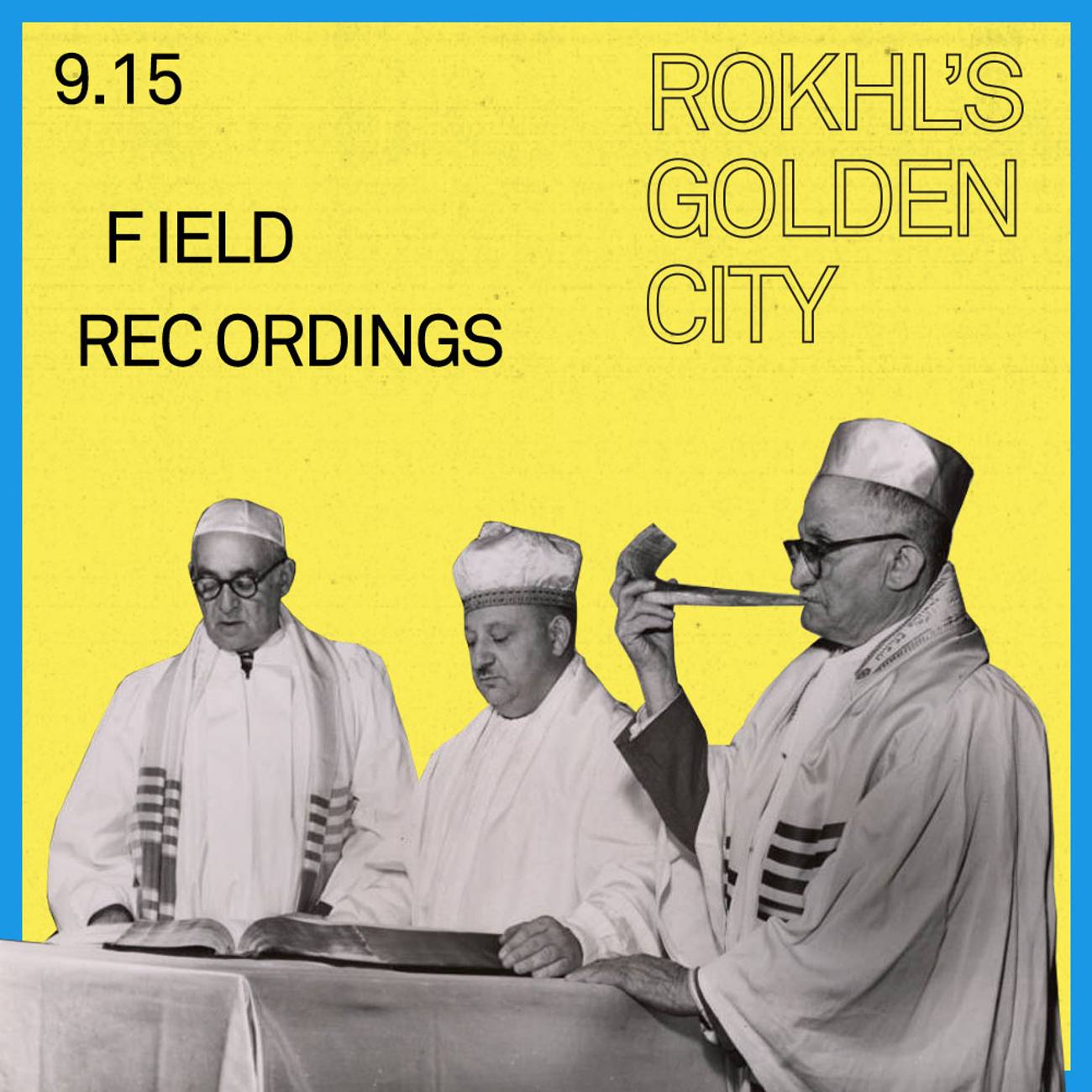

Inset image: Upper Midwest Jewish Archives, University of Minnesota

Inset image: Upper Midwest Jewish Archives, University of Minnesota

Inset image: Upper Midwest Jewish Archives, University of Minnesota

Inset image: Upper Midwest Jewish Archives, University of Minnesota

Just in time for the new year, an oversize package recently arrived inside my tiny New York City mailbox. Inside was a gorgeous gift from my teacher, the poet and scholar Dov-Ber Kerler. Actually, two gifts. First, a bilingual volume of his father’s Yiddish poetry, newly translated by Maia Evrona in a collection called From a Bird’s Cage to a Thin Branch: The Selected Poems of Yosef Kerler. Yosef Kerler was one of the first refuseniks and, according to the publisher, “perhaps the only Yiddish poet to publish poetry written in the gulag.” Maia Evrona is a remarkable translator and I promise to return to From a Bird’s Cage in this space very soon, when I can give it the attention it deserves.

I actually had no idea Kerler was even sending me a copy of From a Bird’s Cage. As happens these days, he had caught my attention when he posted pictures of an altogether different kind of book on social media. It was the kind of image that prompts one to ask, can a notebook be sepia toned? This one, issued by the Education Department of the Workmen’s Circle, according to the stamp at the bottom, certainly seemed to be. The Yiddish at the top of the notebook marked it as belonging specifically to the I.L. Peretz Arbeter-Ring Shuln.

Unlike the light blue, cheery, child-size machberet many of us grew up with, this thing was a genuine Yiddish artifact of another age. It was much bigger than a machberet, and, indeed, yellow-brown, the kind of odd hue rarely found on American school supplies, and no doubt deepened by the passage of time.

On the back cover of the notebook, drawings of the three klasiker, the three founders of modern Yiddish literature, Peretz, Mendele, and Sholem Aleichem, sit atop columns of Yiddish words. The heading reads (in translation): useful and frequent Yiddish words that come from Hebrew. Over 250 words are listed in alphabetical order, including the names of holidays and proper names. It’s a fantastic little cheat sheet for anyone coming to Yiddish without a super solid foundation in Hebrew.

One of the great things about learning Yiddish is that the majority of its words (numerically speaking) are spelled and pronounced phonetically. The frustrating thing about learning Yiddish is that while the nonphonetic, loshn-koydesh (Hebrew-Aramaic) part of the language is much smaller, it’s also very, very important. The only way around it is through it: reading, practice, and memorization.

On the inside front cover of the notebook are even more useful words: days of the week, Hebrew and Gregorian months of the year, and names of the yomtoyvim. On the inside back cover is a chart with side-by-side printed and script Hebrew letters. This last one was what really jumped out at me when I casually clicked on Kerler’s post about the notebook. I had been looking for something just like this!

For the first time, I have a private student whom I have been tutoring in beginner Yiddish. In fact, rather than diving in with one of the many excellent Yiddish textbooks available to beginners, we are using a vintage, 1950s Arbeter Ring reader, one that very much shares its aesthetic with the notebook Kerler sent me. At one point, my student asked for a resource for familiarizing himself with Hebrew script, hence my search. In one of our latest lessons, we had covered the days of the week. And when we got to the chapter about a mayse, a story, my student, an extremely quick and natural language learner, was just a bit thrown by this loshn-koydesh curveball. Up until that point, his previous experience with German had made working through the entirely Yiddish Arbeter Ring reader a breeze, even for a beginner. This was a sign that things were about to get a little bit more challenging.

I want to respect my student’s privacy, so I won’t say too much more about him. But what I will say is that all the cliches about teaching are true. I feel incredibly honored to be teaching him not just Yiddish language, but the culture in which it lived. I love that we’re using Arbeter Ring shule materials because it connects us to previous generations of Yiddish students and their teachers. The ubiquitous images of the klasiker signal the pride they took in Yiddish literature and a tangible connection to them, too.

Perhaps I’m a bit more deeply in my feels on this subject because for the first time in many, many years, I’m observing a proper back-to-school-plus New Year season. I haven’t been a student in way too long, and having no children of my own, “back to school” has been relegated to the category of mostly theoretical. But this year, much to my own surprise, I find myself in a completely novel role: not the student, but the teacher! In addition to my private student, I am (virtually) teaching a semesterlong “Yiddish History and Culture” course for students in the California State University system. And starting in October, I’ll be teaching a brand new, four-week course on Ashkenazi folk magic and religion. It all adds up to the kind of life change that really helps imbue a new year with the proper new year kavone, or intention. Again, all the cliches they say about teaching turn out to be true. Being a teacher means learning much more than you could imagine.

Of course, the thing about a new year is that whether or not it’s different, it’s still new. Living within the Jewish calendar, we inhabit a dynamic between the cycle and the individual. We repeat and we renew. For the last two years, right around this same time, I’ve written about my friend Jeremiah Lockwood and his latest musical incarnations. For many years, he’s been leading High Holiday services for Because Jewish and creating new music for the occasion with his band, Sway Machinery. This year is both different and the same.

In 2022, Lockwood was celebrating the 15th anniversary of his 2007 Hidden Melodies Revealed project, which, in his own words, was “conceived as a concert version of the holiday liturgy, reconfigured through the sounds of 21st century rock and international popular music,” integrating “storytelling, experimental animation and an orientation towards pleasure and community.”

For 2023, he has dreamed up something called “The Dream Past: A Sonic Conjuring.” Appropriate to both the season and the topic, Lockwood excels at going deeper into his obsessions, like the virtuoso cantors he studies, conjuring uniquely compelling variations on a yearly theme.

The khazn, the cantor, occupied an ambiguous role in the traditional Eastern European Jewish community. He was a kley-koydesh, a key religious functionary, like a rabbi. But unlike a rabbi, he wasn’t necessarily a figure of great learning, nor did he necessarily come with ordination comparable to that of the rabbi. Rather, the khazn was an artist who arrived at his position by way of apprenticeship. He was the intermediary between the congregation and God, pleading on their behalf. But his performance was in danger of being too good, too compelling. It had the potential to distract or pull focus away from the heavenly, back onto the earthly. It is in that liminal zone between pleading and performance that Lockwood finds inspiration.

Specifically, Lockwood has been working with mid-20th-century field recordings of live cantorial davenings created surreptitiously, by devoted fans, aka cantorial bootlegs. As he writes in a self-produced promotional zine, “Live davenings, as intimate objects that seduce listeners with the promise of unmediated access to the sounds of the past, were understood by the collectors as an ameliorative against loss.”

Centuries ago, European Jews created “custom books,” reference manuscripts that also aimed to protect against cultural loss, as well as stabilize religious observance, and capture their lived experience. In Picturing Yiddish: Gender, Identity, and Memory in the Illustrated Yiddish Books of Renaissance Italy, historian Diane Wolfthal analyzes the illustrations in one of these books, known today as the Paris book of customs. Written mostly in Yiddish, it was produced in Italy, sometime in the early 16th century, and shows how to observe Jewish ritual, both in the synagogue and at home, perpetuating Ashkenazi customs for families now living in Italy.

What is so fascinating about this custom book is not the quality or brilliance of its many illustrations. They are, to use a technical term, not good. But because the illustrator was at liberty to create whatever images he desired, his choices reflect daily Jewish life, not as it was supposed to be, but as the individual experienced it.

As Wolfthal describes it, he “repeatedly ignores the thrust of the text, which focuses on synagogue worship, and instead illustrates scenes of landscapes, animals, hybrid creatures, or Jews celebrating holidays outdoors or at home. Sometimes he does this by ignoring a long passage that describes synagogue liturgy and focusing instead on the one phrase or section that will enable him to produce an image of a custom that was observed at home.” Relatable.

Further on, she writes that “folio 50r describes the synagogue services for Rosh Hashanah … and finally concludes with a line that reads, ‘And then one goes home and eats and drinks well and is happy.’” Rather than illustrating what happens in the synagogue, the scribe-artist focuses on this single line, developing “a scene of drinking. He shows two men, one holding a huge jug and glass, and another whose banderole is inscribed, ‘Good wine makes one happy.’”

Similarly, on the facing page, where the text describes the Rosh Hashanah morning and evening services, the illustration depicts “eating and drinking at home … The scribe emphasizes their act of drinking through his caption, ‘He makes kiddush on Rosh Hashanah and drinks.’”

This time of year, so many of us become preoccupied not just with the tasks of tshuve and tfile, prayer and repentance, but the overriding self-doubt of am I doing this right? It’s reassuring to be reminded that Jews of the 16th century also had to address this question for themselves. Moreover, even in the act of regularizing observance, the unknown scribe-illustrator of the Paris custom book prioritized his own lived experience, and, to paraphrase Jeremiah Lockwood, remained defiantly oriented toward his own pleasure.

Finally, I want to link the unknown illustrator of the Paris custom book with the recently departed Jimmy Buffett. I’ll admit I was not among his many devoted fans. However, in the process of translating one of his songs into Yiddish back in 2021, I developed a respect for him and his songwriting craft. He brought joy to millions, and by many accounts, was a pretty mentshy guy. His 1973 novelty hit “Why Don’t We Get Drunk …” certainly resonates with our cheeky Italian custom book illustrator, impatient to get home from synagogue and quench his thirst. When I adapted the song into Yiddish, I imagined it from a woman’s point of view, impatiently watching her husband make Friday night Kiddush, pleading with him to skip to the good part. It’s nice to know that even when we’re not doing it right, we’re still kinda doing it right.

LIVE: Jeremiah Lockwood and Sway Machinery will take part once again in the “Bowl Hashanah” musical celebration of the holiday at Brooklyn Bowl, Saturday morning, Sept. 16. Morning services followed by catered lunch. Tickets here … In the days between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, Lockwood and The Sway Machinery will debut a new music program called “The Dream Past: A Sonic Conjuring.” Sept. 21, at Union Temple House of CBE, 17 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn. Tickets here … And for Yom Kippur, Sway Machinery will be joined by special friends for a livestreamed performance at Relix Studios in Manhattan. More information here.

ALSO: Workers Circle will present live virtual Rosh Hashone and Yom Kippur programs featuring music, songs, and a focus on activism ... It’s not too late to buy yourself a gorgeous Radical Jewish Calendar for 5784 ... And speaking of going back to school: Fall term Yiddish classes are starting very soon for both YIVO and the Workers Circle.

Rokhl Kafrissen is a New York-based cultural critic and playwright.