It’s the most wonderful time of the year: the time for “best of the year” lists. And it’s only appropriate to reference a Christmas song, because some of the year’s best Jewish children’s books featured interfaith families, as well as interfaith appreciation and cooperation and explorations of Jewish identity, including not one but two unexpected b’nai mitzvah. It was also a great year for biographies, especially of lesser-known Jewish women. And in a less-positive sign of the times, books for older kids often featured contemporary antisemitism.

There was an abundance of great Jewish picture books in particular this year, and a healthy variety of them as well. Along with the usual slew of holiday books, this year’s picture books ran the gamut from fiction to nonfiction, from Shabbat stories to everyday childhood stories with a Yiddish flair. And their settings ranged from Iraq to the American Midwest, from the 17th century to today. That’s good news for kids—and for parents, who can read the books below again and again with pleasure.

The Christmas Mitzvah by Jeff Gottesfeld, illustrated by Michelle Laurentia Agatha. This beautiful (both visually and in terms of its story) book tells the fictionalized story of Al Rosen, a Jew who for decades did Christians’ jobs for them on Christmas Eve so they could celebrate with their families. The book starts out with an acknowledgement that it is fine to appreciate another’s religious traditions: “Al Rosen was a Jewish man who loved Christmas,” it reads. “It wasn’t his holiday … [b]ut what could be bad about peace on earth and goodwill to humanity?” With a warm palette emphasizing the feel-good nature of the story, the illustrator depicts the people Al helped as varied as any urban population—not just in terms of race, ethnicity, and religion, but in terms of their clothes, hairstyles, and other distinctive features (e.g., a nose ring).

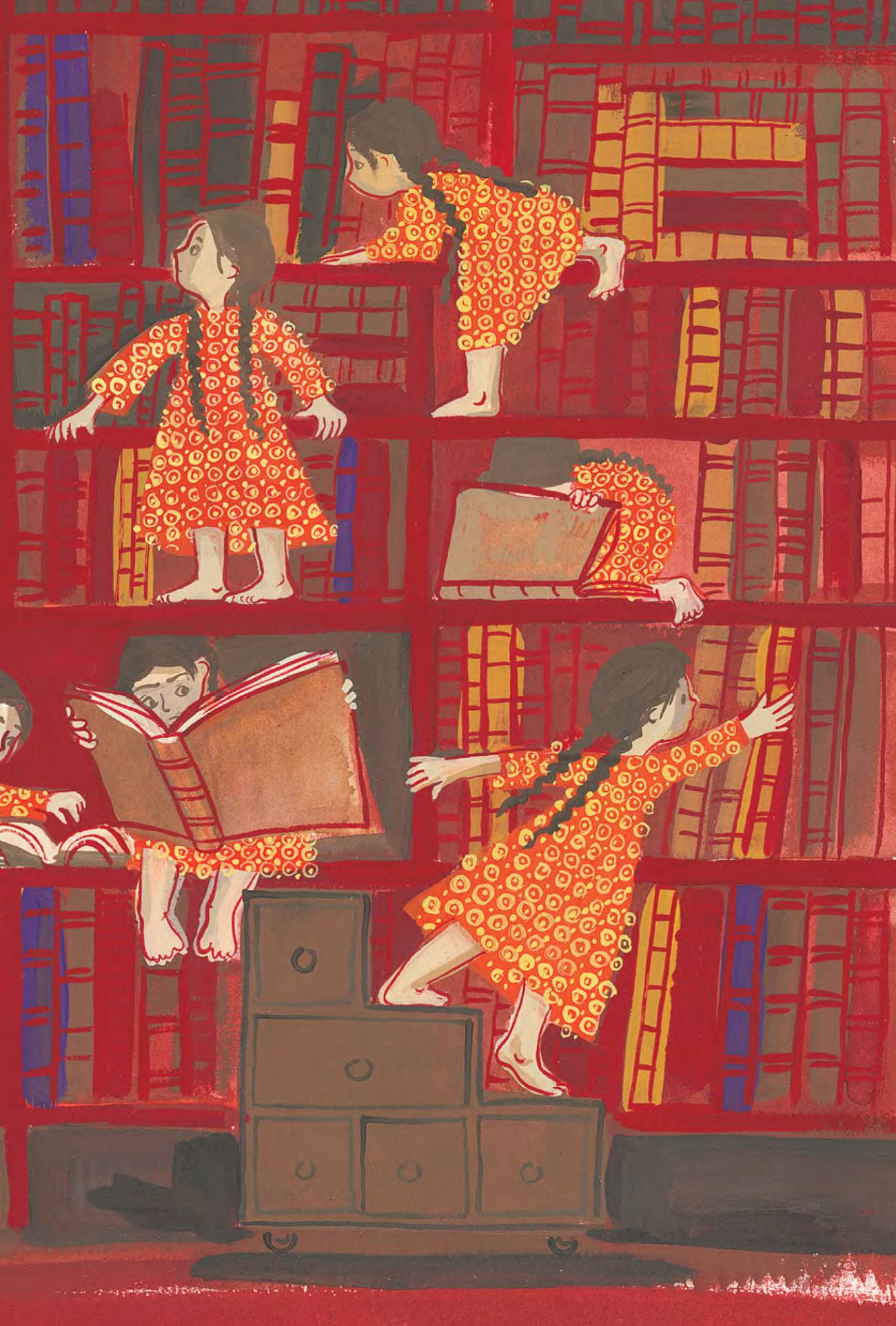

Lights in the Night by Chris Barash and illustrated by Maya Shleifer. This gentle story of Shabbat is told through not only the prism of the candles we light on Friday night, but also the other sources of light that illuminate our way and comfort us, including a nightlight that comforts a child until morning. The book follows an unnamed child and his parents as they head out to a coastal Shabbat picnic. The soothing mostly gray and yellow color palette complements the rhyming text perfectly. With glow-in-the-dark ink (hold the pages under a flashlight for a bit first), this oversized board book will delight young readers. (While Lights in the Night won’t be available on Amazon until February 2022, it can currently be ordered from its U.K. publisher, Green Bean Books.)

Baby Moses in a Basket by Caryn Yacowitz, illustrated by Julie Downing, and Esther Didn’t Dream of Being Queen by Allison Ofanansky, illustrated by Valentina Belloni. Most holiday books are awful, but the Passover-themed Baby Moses in a Basket and Purim-themed Esther Didn’t Dream of Being Queen are exceptions to the rule. Employing a songlike structure and rhyme, Yacowitz imagines the animals that might have protected Moses until he was rescued by Pharaoh’s daughter. Ofanansky manages to successfully simplify Purim’s complicated plot, and her conceit of comparing Esther to Cinderella—another orphan who became queen—works so well it’s hard to imagine it hadn’t been done before. But as her Esther says, “[W]hen I became queen, my story was only beginning.”

From ‘A Bear for Bimi,’ by Jane Breskin Zalben, illustrated by Yevgenia NaybergKar-Ben Publishing

Gitty and Kvetch by Caroline Kusin Pritchard, illustrated by Ariel Landy. The optimistic Gitty and her cynical avian sidekick Kvetch will bring smiles to both children and the adults who read to them. The story is a simple one: Gitty’s painting is ruined and her seemingly infinite optimism turns out to not be infinite after all. But friendship saves the day. Peppered with Yiddish words, this book makes a great read-aloud. And I loved that Kvetch’s essential nature remains the same at the end of the book—no feel-good transformation here.

A Bear for Bimi by Jane Breskin Zalben, illustrated by Yevgenia Nayberg. This addition to picture books about refugees is told with a light and child-friendly touch. Although the references to Judaism are subtle (the names—Evie and her father, Abe Gold—and the fact that Evie’s grandparents came to America from “another country”), Jewish values permeate this story. Evie and her parents welcome their new neighbors, who are Muslim refugees, including a son, Bimi, around Evie’s age, by helping them furnish their new home. They ultimately get the whole neighborhood (even the initially suspicious Mrs. Monroe) on board. Children will relate to Evie’s impulse to help and to Evie’s and Bimi’s exchange of items precious to them (Evie gives Bimi the title bear; Bimi gives Evie a marble from his grandmother’s garden). Illustrated by one of my favorite illustrators working today, Yevgenia Nayberg, the bright, warm colors and bold shapes add to this book’s appeal.

The Story of Bodri by Hédi Fried, illustrated by Stina Wirsén, may be a picture book but it is not for the youngest readers. Fried, a Holocaust survivor, calls this the story of Bodri, her dog, but it is really her and her sister’s story. She writes in strong, direct, but child-friendly prose. Of her best friend she says, “Marika and I were almost the same height and we were both very good at whistling. She ran faster than I did, but I was better at reading … The only difference between us was that we said different prayers. Marika went to church and I went to synagogue. I was Jewish. She wasn’t.” But Fried does not shy away from telling the hard truth of what happened to her and so many others. Wirsén’s illustrations are stunning, with washes of color. And like Fried, she does not shy away from the harsh realities of the Holocaust, including an illustration of Hédi and her sister behind barbed wire, and one of a nearly bald Hédi reuniting with Bodri. The author never mentions what became of her parents but adult readers will draw the logical, tragic conclusion.

Dear Mr. Dickens by Nancy Churnin, illustrated by Bethany Stancliffe; Osnat and Her Dove: The True Story of the World’s First Female Rabbi by Sigal Samuel, illustrated by Vali Mintzi; and Try It!: How Frieda Caplan Changed the Way We Eat by Mara Rockliff, illustrated by Giselle Potter. Have you ever heard of Eliza Davis? What about Osnat Barzani? Frieda Caplan? Me neither, at least not until these picture book biographies. Eliza Davis wrote letters to Charles Dickens, a writer she much admired, calling him out for his antisemitism. Remarkably, not only did he write back, he changed his mind because of her—making Dear Mr. Dickens a book about not just the power of an individual, but the power of words. As for Osnat Barzani, she was born in 1590 in modern-day Iraq and was permitted by her father to study Torah as a girl, conditioning her marriage on being allowed to continue. She became head of a yeshiva after both her father and husband died, predating the woman we think of as the first female rabbi, Regina Jonas, by over 300 years (although Rabbi Jonas may still be the first ordained female rabbi). Although some of Barzani’s letters survive, there are many gaps in what we know about her, and Osnat and Her Dove imagines what her life might have been like. (The book might have focused more about her teachings than her legendary miracles, but that’s a minor quibble.) Try It! introduces us to “produce pioneer” Frieda Caplan, who brought many previously “exotic” foods to American supermarkets. If your supermarket carries seedless watermelon, kiwis, and spaghetti squash, thank Frieda. I only wish that the story, told in the backmatter, of how she handed back the award for Produce Man of the Year until it was renamed Produce Marketer of the Year, had been included in the text of the book itself. Illustrator Giselle Potter makes all the veggies and fruits appealing, choosing to showcase a range of colors and textures.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t include The People’s Painter: How Ben Shahn Fought for Justice With Art by Cynthia Levinson, illustrated by Evan Turk. I’d never heard of Shahn but my artier and/or more politically aware friends had. With Turk’s dramatic linoleum block illustrations, Levinson tells of Shahn’s early beginnings in Russia and follows his personal life and the evolution of his art and how he fought for the underdog, always, and portrayed the less ideal side of American life. Levinson’s clever last line, tying together an early mention of how Shahn drew in the margins of his book of Bible stories, emphasizes how he championed the marginalized.

From ‘Lights in the Night,’ by Chris Barash and illustrated by Maya ShleiferGreenhill Books

Summer of Stolen Secrets by Julie Sternberg, and Recipe for Disaster by Aimee Lucido. Despite their similarities—both books feature interfaith marriages, estranged families, and grandmas—these two books are actually quite different. In Summer of Stolen Secrets, rising eighth grader Catarina is sent to Baton Rouge to spend the summer with the paternal grandmother she’s never met. Her seemingly stern grandma is beloved by the employees of the family department store she runs and owns. As Catarina gets to know her grandmother, she discovers that the roots of her estrangement from the family date back to the Holocaust. In Recipe for Disaster, when Hannah, amateur baker and daughter of a non-Jewish father and a nominally Jewish mother, attends her best friend’s bat mitzvah, she finds the melodies oddly familiar, “as if little bits of Hebrew ha[d] leaked into [her] brain over the years, like sweet syrup soaking into a pound cake” despite having set foot in a synagogue only a handful of times. (That is but one example of Lucido’s successful use of food and baking metaphors throughout the book.) Hannah explores her Jewish identity by comparing herself to her best friend Shira, her new friend, Guatemalan- and Christian-born but Jewish-identifying Veronica, her live-in grandmother, and her estranged rabbi aunt. An antisemitic incident brings her understanding of her Jewish identity into sharper focus. As Hannah studies for the bat mitzvah her parents have forbidden, Lucido includes the actual Hebrew text of her parsha along with an English translation—the first time I have ever seen this done in a work of fiction, for children or adults. Lucido does not take the easy way out by giving Hannah a “fun” parsha but, by virtue of her spring birthday, assigns her a parsha from the notorious rule-oriented Leviticus.

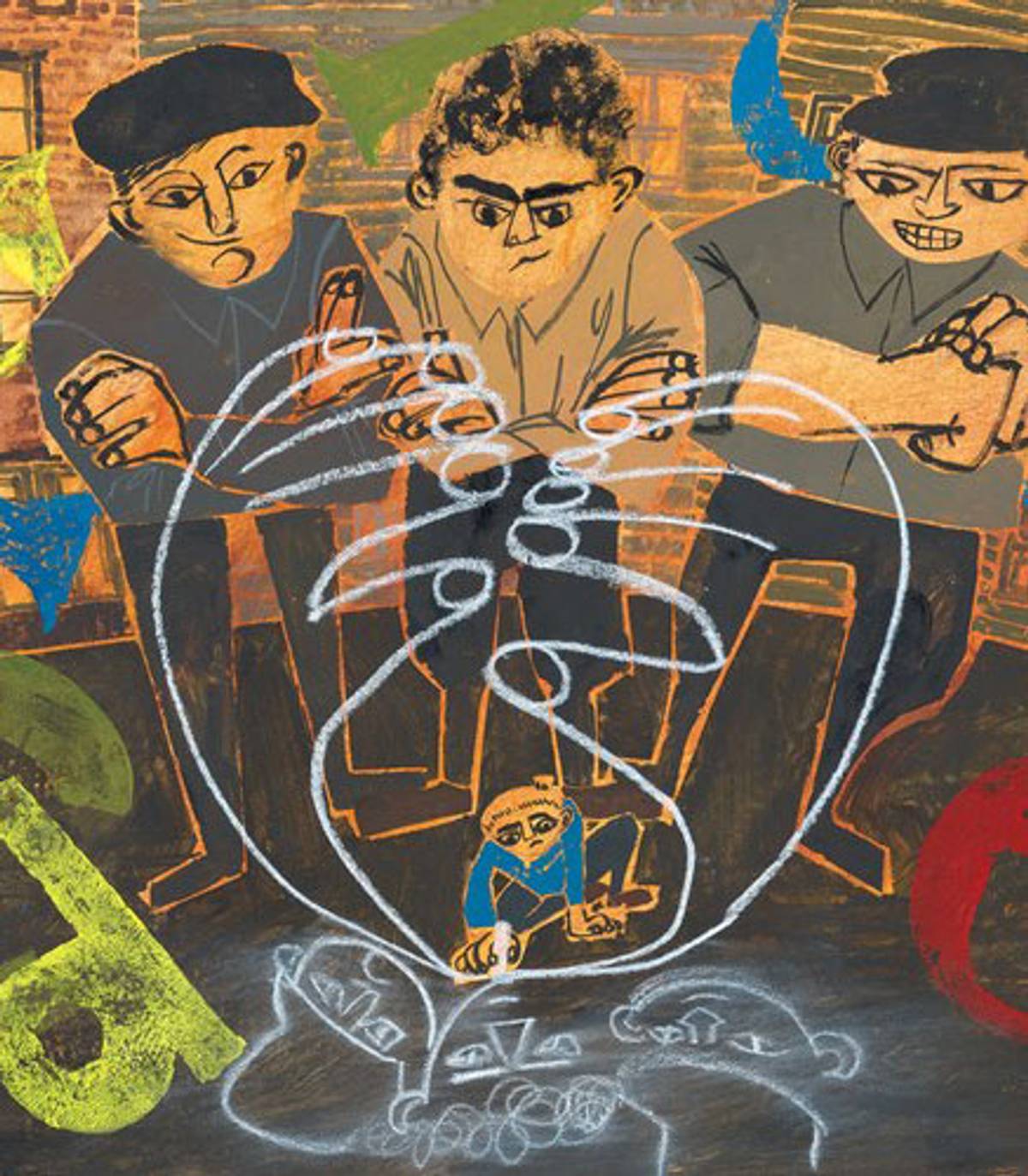

Linked by Gordon Korman. A series of 27 swastikas are found around Chokecherry, Colorado, a small town that had no Jews (or so its residents thought) until a group of paleontologists and their families, including one Jewish family, arrived after a discovery of dinosaur fossils. At the same time, class clown and prankster Lincoln (“Link”) Rowley discovers his Jewish heritage and decides, to the surprise of everybody, including his parents, to have a bar mitzvah. The title refers not only to Link himself, but to the students’ project to make a paper chain of 6 million links to represent the 6 million Jews murdered in the Holocaust. While Recipe for Disaster may appeal more to girls, Linked, with its multiple narrators—some male, some female—and Korman’s humor, has more universal appeal.

From ‘The People’s Painter: How Ben Shahn Fought for Justice With Art,’ by Cynthia Levinson, illustrated by Evan TurkHarry N. Abrams

Sorry for Your Loss by Joanne Levy. Evie’s family owns a funeral home, but instead of being embarrassed by this “weird” or “creepy” profession, she hopes to take over the funeral home someday, as she sees that the services her parents provide are necessary. As she tries to comfort a child her own age who has lost his parents, Evie realizes in a visceral way what a very hard job her parents have. While exploring the nature of grief, Levy also teaches the reader much about Jewish funeral rites, including preparing the body for burial, in the same matter-of-fact way that Evie has been taught by her parents. Not for every child but a much-needed addition to children’s fiction featuring Jewish ritual.

RBG’s Brave and Brilliant Women: 33 Jewish Women to Inspire Everyone by Nadine Epstein, with an introduction and selection by Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Divided by time periods—which span the biblical era to the 20th century—each section begins with a quick sketch of the times the women lived in. Profiling women who range from politicians to scientists and mathematicians to artists to educators to freedom fighters, from women who lived in the Middle East to those from Europe or the United States, this book offers an excellent smorgasbord of accomplished Jewish women. Some you’ve heard of: RBG herself, Betty Friedan, Anne Frank, Golda Meir. Some you probably haven’t: Gracia Mendes Nasi, Rebecca Gratz, Florence Prag Kahn. For children who enjoy biographies but may find full-length books intimidating, this book of short sketches may prove just the ticket. Flip to any page and you’ll find someone interesting.