Teaching Yiddish Modernism in Tel Aviv

Sweet summer heat

Tablet Magazine

Tablet Magazine

Tablet Magazine

Tablet Magazine

Usually, Yiddishists do not spend their summers at the beach. Even card playing was deemed antisocial behavior at Camp Boiberik (1913-79), where the adults were encouraged to gather untern boym, under a resplendent tree, and listen to lectures on Yiddish literary and cultural matters instead. Ever since 1968, students of Yiddish language, literature, and culture have endured the sweltering heat at the Uriel Weinreich Program in New York City, and that is where, with the ink still wet on my M.A. degree from Brandeis, I got my first hands-on experience teaching Yiddish literature. Back then, it was all hands on deck, because the mother ship of Yiddish studies had gone down, torpedoed by the joint forces of Hitler and Stalin, while the survivors massed on the American mainland looked on with indifference. Rather than waste our time on the beach, where all we could do was search for debris, those few of us who regrouped on this side of the Atlantic came up with a rescue plan: to spend a few solid weeks every summer teaching Yiddish in Yiddish.

This summer, there were seven such programs, seminars, marathons, and retreats to choose from: in New York, Amherst, Montreal, Warsaw, on the shores of Zegrze Lake (outside of Warsaw), Brussels, and Tel Aviv, not counting special camps for musicians and music lovers. The Naomi Prawer Kadar International Yiddish Summer Program at Tel Aviv University, where I have just finished teaching, dates back to 2006, and this year boasted a student body from 14 different countries; most notably, Georgia. Of the 16 students in my advanced seminar, five were from Israel, five from the States, two from Poland, and one each from the U.K., Germany, Ukraine, and Argentina. All but three were certifiably young; otherwise, teaching a survey course on Yiddish modernism, from I.L. Peretz to Benjamin Harshav, might not have been feasible.

Modernism, let’s face it, is only for the young. To be sure, my course began with two “precursors,” Peretz and the American Yiddish poet, world-traveler and translator, Yehoash, both of whom came to modernism in their later years, but almost everyone else on the roster was a paragon of youth, from Peretz Markish, who burst onto the scene as a poet of the Bolshevik revolution at age 22, to Pinkhes Kahanovitsh, aka Der Nister, who found his voice in the prose poem at the age of 24, to Moyshe-Leyb Halpern, who brought the apocalyptic poema (long narrative poem) into Yiddish at age 30, not to speak of the two boy wonders, Y.L. (Judd) Teller, who made his poetic debut at age 14 and H. Binyomin (Hrushovski-Harshav), who did it at 19. When Rosa Lebensbaum switched from Russian to Yiddish and adopted the pen name of Anna Margolin, she was all of 33 years old, but felt that she had arrived on the New York literary scene too late in life.

Yiddish modernism itself was so recent a phenomenon that I personally had known seven of the 24 poets and prose writers whom we tried to cover in this minisemester: Yosl Birstein, Yankev Glatshteyn, Benjamin Harshav, Gabriel Preil, Avrom Rinzler, Avrom Sutzkever, and Aaron Zeitlin. Most of my students, moreover, came of age after the seismic shift from new criticism to literary theory had already happened, so they were not at all put out by the alphabet soup of isms—cubism, expressionism, imagism, introspectivism, symbolism, surrealism—and were ready to indulge my valiant efforts to create Yiddish equivalents for “positive eclecticism” (pozitiver farsheydn-minikeyt) and polyphony (filshtimikeyt), which were not such a far cry from the kalidoskopishkeyt (kaleidoscopic art) of introspectivist fame.

As summer courses go, ours is on the far end of the intensive spectrum. The two morning slots of formal instruction in language and literature take the beginners to advanced students from 9:00-12:30, followed by afternoon workshops in conversation, song, theater, decoding Yiddish manuscripts (hugely popular), writing and translation and a research seminar, followed by a rich array of extracurricular activities off campus that usually don’t start until 8:00 p.m. (When did I think my students would have time to prepare the primary, let alone the secondary readings? I naively thought: over the Friday-through-Sabbath-break, but on Friday July 14, Yaad Biran led a Yiddish-themed field trip to the Harod Valley in the north, not to mention other attractions and distractions in a city that never sleeps.) Those who had already achieved a level of fluency kept the language synapses alive by speaking Yiddish 24/7.

Thanks to the utopian environment we create on the Tel Aviv campus, where for one month every summer, schmoozing, singing, performing, reading and writing in Yiddish are a given, requiring no justification, I had the chutzpah to try something new, something that to the best of my knowledge had never been done before. With a captive audience of 16 highly motivated students, I decided to survey the whole of Yiddish modernist writing from its spectacular rise to its sudden demise; to follow its uncharted course from Kyiv to the kibbutz; and to gain some facility in the modernist tool kit. Without much ado, I zeroed in on the what and how of Yiddish modernism. A routine part of each class was the hunt for neologisms, foreignisms, and archaisms in the poetry and prose of 24 Yiddish poets, prose writers, and one playwright (Peretz) whom we followed across space and time. The maximalist agenda of the modernists—to create a new language, invent new genres and don new identities—was the perfect complement to the 80-plus students and teachers from around the world who found refuge from the Tel Aviv heat and the nonstop protests against the judicial overhaul by immersing themselves in all things Yiddish. If anything, the marching, chanting, and hooting on the streets were the perfect backdrop to reliving the modernist moment.

But why did our poets, prose writers, playwright, and critics, joined by painters, sculptors, and graphic designers, choose to go this difficult route via Yiddish? The various manifestos and personal testimonials strategically placed throughout my 398-page course packet provided some compelling answers. Fresh from the political arena themselves, the three budding intellectuals in Vilna who launched Di literarishe monatsshriftn (The Literary Monthly) in 1908 set out to mobilize those still-vital forces within the Jewish nation and unify them behind a Yiddish high culture that transcended political divisions. “For art! For young beautiful Yiddish! And for the eternal language of the prophets!” proclaimed the poets and artists who in 1919 bonded together in Lodz to publish the first Yiddish expressionist journal, Yung Yiddish. Three years later, the peripatetic poet Uri-Zvi Greenberg seized upon expressionism as the voice of a new humanity. “We proclaim the millionfold head-and-heart individualism,” cried the inaugural issue of Albatross, “the heroic Man of Wounds”—a secular Jesus—“who stands in all his glory, as large as the earth, all eyes and ears and lips, with his 365 veins pumping into the life stream deeper, deeper.” Not for himself alone did Greenberg speak, but for all “the lone and homeless poets as they roam through foreign lands to the many centers of the Jewish people’s exterritoriality.”

In the newest metropolis of Yiddish, New York City, meanwhile, three Introspectivist poets jettisoned the notion that Yiddish was synonymous with national, collective or parochial concerns. “We are ‘Jewish poets’ simply because we are Jews and write in Yiddish,” they declared. “No matter what a Jewish poet writes is ipso facto Jewish”—their cosmopolitanism underscored by using the very un-Yiddish phrase ipso facto. “As to Yiddish as a language instrument, we believe that our language is now beautiful and rich enough for the most profound poetry;” in their view, indeed, Yiddish poetry had already become “a particular stream in the whole contemporary poetry of the world.” As we read these fighting words, halfway into our course, we were now beginning to ask a different question: Why not Yiddish? Was there ever a Jewish language better equipped to register and weather the upheavals of history and exterritoriality?

To break most dramatically with the generation of Yiddish writers who came before, it was necessary to mix and match disparate cultures, mythologies, linguistic registers, voices and even genres. “Positive eclecticism” is the name that Harshav used to describe this modernist method, a more precise term by far than “heterogeneity,” which suggests a mere mishmash. So when Der Nister made his formal debut in the pages of The Literary Monthly with a prose poem called “Poylish” (Polish), everything about it was deliberately provocative. If this was supposed to be an ethnographic description of a Hasidic wedding dance, presumably called “poylish,” then why was the style so artful and artificial? If this was prose, then why did each paragraph read like the stanza of a poem, complete with alliterative spells and long rhythmic passages? Why did the klezmer musicians suddenly morph into dense kabbalistic imagery, then into the intimate embrace of two lovers lifted straight out of the Song of Songs? What was worse, the open eroticism or the eclecticism? Both were anathema to someone like S. An-ski, the Russian revolutionary turned Jewish ethnographer, for whom the whole point of reviving Hasidic folklore was to make it sound as if it came directly from the folk, whereas Der Nister was intent on erasing the boundaries between sight, sound, and sensation; male and female, old age and youth, night and day, this world and the next, word and music. Change the musical accompaniment and the language so redolent of Jewish myth, and Der Nister’s “Polish” could be played alongside the four symphonies of the Russian symbolist, Andrei Bely.

Yiddish modernism was an echo chamber of dissonant and dissident voices. In his play A Night in the Old Marketplace, Peretz orchestrated the screaming contradictions of Jewish life by rhyming one character’s lines with those of another. In A Night, his disciple, Moyshe-Leyb Halpern, veered from oracular to parodic to hallucinatory voices from one canto to the next, each with its own rhyme scheme and meter. Death was the only escape from the speaker’s waking nightmare, and from the ubiquitous presence of his mentshele, his blaspheming double. And all this was but a prelude to what came next, in rapid succession: Moyshe Kulbak’s sprawling expressionist collage, The Messiah of the House of Ephraim, Dvora Fogel’s cubist montage, the multiple personae of Anna Margolin, Celia Dropkin, A. Leyeles, and Yankev Glatshteyn. Maybe there was a reason no one had attempted a survey course like this before?

At least there was plenty of rhyme. Classical prosody had come so late to Yiddish verse that the same poets who began to experiment with free verse and free rhythms also mastered the most intricate rhyme schemes, gramen-shlislen. Enter Peretz Markish. Even with the help of Uriel Weinreich’s 1955 essay on multisyllabic Yiddish rhyme, my students were not prepared for “mayn nisht visn vu ikh GEY do” (my not knowing where I’m going) to rhyme with “tsu der aKEYde,” (to the Akedah, the binding of Isaac on Mount Moriah), and more drastically still, the inverted syntax of “vos zen nor ikh ALEYN ken” (that see I alone can) with “mayn flakern un BENken” (my flaming and longing). So revolting was the imagery in the opening canto of Di kupe (The Heap), Markish’s anguished response to the Ukrainian pogroms, that one could easily miss the line count, structure and precise rhyme scheme of a sonnet. Here Markish tried to demolish the classical sonnet, as he turned the heavens upside down and upended the Kaddish. Let the sight and stench of rotting corpses heaped in the shtetl marketplace remain as a permanent blight against the heavens, against the covenant and against the church nearby. Here rhyme was almost unbearably pitted against reason.

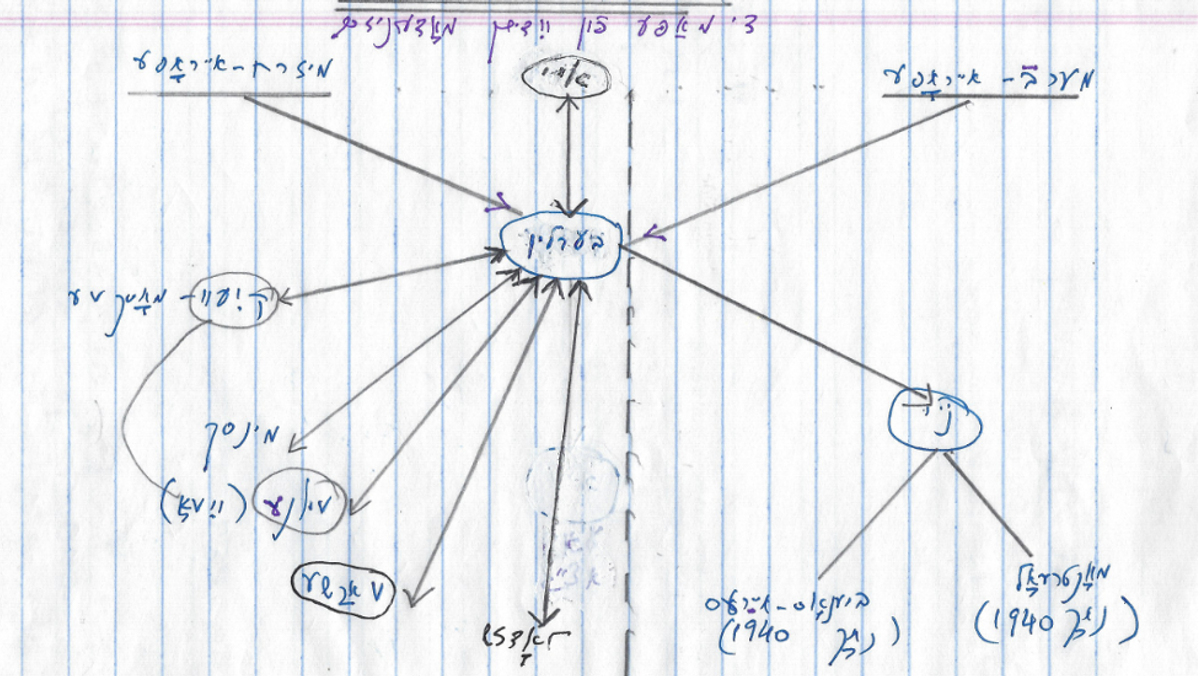

So the what and how of Yiddish modernism were inseparable from the nightmare of history and inexplicable without a crash course in Jewish exterritoriality. For the briefest moment in Jewish time, from 1921-24, all roads led to Weimar Germany, where an astonishing 39 Hebrew and Yiddish publishing houses sprang into existence, and to Berlin in particular, where members of the Russian, Hebrew, and Yiddish avant garde went into exile, there to congregate in separate cafés. (Kafka too made a brief appearance.) To drive home the ubiquity of Jewish homelessness, I drew a primitive map, with multiple arrows pointing to and away from Berlin, in dead center:

Yiddish modernism created its own cognitive map of the world, where major cities replaced political boundaries; where Mandatory Palestine, sandwiched at the top between Western and Eastern Europe, was as transitory a place as any other; and where New York, gloriously isolated to the right of the dotted line, was in open competition with the cultural capitals of Kyiv, Moscow, Minsk, Vilna, Warsaw, and Lodz, huddled along the left bank of Yiddishland. (One student rightly protested that I had left out Paris.) Precisely because the map was not drawn to scale, it captured Weimar as the most capacious capital of Yiddish and world modernism—until it wasn’t.

Taking a hard look at the timeline of Yiddish modernism left no doubt that by 1940, the party was over. In that year alone, In zikh ceased publication in New York; Teller published Poems of the Age, an astonishingly original work, and gave up Yiddish altogether; and 27-year-old Avrom Sutzkever invented a new poetic language in Valdiks (Of-the-forest), just months before Vilnius was retaken by the Red Army, followed a year later by the Wehrmacht, whose mobile killing units turned Vilna into the first major site of the Holocaust. There was just enough time for a few copies of Valdiks to reach New York—by which time Sutzkever himself had become a different poet.

By any measure, our course should have ended then and there. All the signs were apocalyptic. The utopian dreams of merging Yiddish culture with modern art; of Yiddish poets and prose writers occupying their rightful place in the world literary pantheon; of the Yiddish language continuing to fashion a world in flux even as it proved itself capable of supreme self-discipline—these were the detritus of the battles lost. The heap of corpses now reached to the sky.

One after the other, the surviving modernists covered their tracks and did penance for whoring after strange gods. H. Leivick, I showed my students, eliminated all of the social dramas from his so-called Complete Works of 1940, leaving only the Comedy of Redemption. His youthful railings against the dead weight of Yiddish poetry and fiction that we read at the beginning of the course would never be republished. Moyshe Nadir, ever the enfant terrible, titled his last book of verse, Moyde ani (I Confess, 1944). As early as April 1938, Yankev Glatshteyn wished the world an angry farewell and announced his voluntary return to the “ghetto,” thus changing the direction of Yiddish secular culture from Forverts (forward) to backwards. Even Anna Margolin, who had stopped writing long before, instructed her translator, Leyb Feinberg, on Feb. 4, 1946 (as cited on page 254 of the course packet), to reverse the last two lines of her famously subversive poem, “I Was Once a Young Man,” so as not to offend the memory of the murdered Jewish people.

Yet the course was not yet over, not by a long shot. Yiddish modernism, so light on its feet; so tied to little magazines, here today, gone tomorrow; every ism so prone to schisms (a bon mot of Chana Kronfeld’s) was granted an afterlife. Though the patient was terminally ill, three vital signs made resuscitation possible: every once in a while, a mentor came to the rescue; the saving remnant of the Jewish people regrouped in the State of Israel; and with a little help from their teachers, our students found a usable modernist past.

Timely interventions, the course packet revealed, were nothing new to Yiddish culture. From her intimate autobiographical sketch, the students knew the story of 18-year-old Malka Hefetz, who had just marked the publication of her first English poems in Alarm, a Chicago-based little magazine, when her mentor and father figure Kalman Marmor took her out to a concert, then to a café, for a cup of coffee. America, he explained to her, had so many poets—good, bad, and everything in between—while in Yiddish, they were so few in number. “Stay with us, Malkele,” he pleaded. “Write in Yiddish, even if it’s hard to get something published; even if there’s no premium on originality.” Lonely as Yiddish was, Yiddish modernism would be even lonelier. And in the last personal testimony that we read, the preface to H. Binyomin’s Take af tshikaves (For the sake of curiosity, 1994), playfully subtitled Geblibene (remaindered) instead of Geklibene (collected), lider (poems), we learned of two awakenings of H. Binyomin’s dormant Yiddish muse: one that Dr. Max Weinreich provoked in 1959, and another that happened in the 1970s and ’80s, when Avrom Sutzkever welcomed the errant poet back into the pages of Di goldene keyt, the gold standard of Yiddish literature and scholarship. Harshav thanked Sutzkever for rescuing his verse from the margins of forgetfulness, di marginesn fun fargesn.

A similar encomium could have written by our students. Of all of the extracurricular activities that we had planned—concerts, outings, lectures, colloquia—only one was billed as a pilgrimage, to the apartment building in the upscale part of town where Sutzkever had once lived, now marked by a trilingual memorial plaque put up by the Tel Aviv municipality. Mira Sutzkever, the poet’s younger daughter, was still in residence, so three weeks before I picked up the phone to ask whether she would meet with us. Mira was delighted. July 16, the date we had chosen at random, was the day after her father’s 110th birthday.

It was murderously hot and humid, even at 6 in the evening. But our smiling faces do not lie, for the stars were aligned. Mira showed us sketches her father had drawn of her as a child; read us from one of many letters she once received from her ardent admirer, the poet Itzik Manger; gratefully accepted a Yiddish literary calendar designed by Etl Niborski, the daughter of our teachers Eliezer Niborski and Miriam Trinh, where Sutzkever’s portrait marks the month of July; then heard four students read translations of her father’s poem “Self-Portrait” in their native languages: English, Polish, German, and Ukrainian. Together, on that day, we had turned hot and humid Tel Aviv into a city for lovers—of Yiddish.

Thanks to Sutzkever Yiddish modernism would live again—on native ground. In “Self-Portrait,” the poet’s time travel through memories both horrific and salvific had ended in a barrier of glass. Within a few years, however, that impasse birthed his extraordinary cycle of prose poems, Green Aquarium, which, like Der Nister’s, used figurative language, rhythmic prose to mix the real and the imagined, the dead and the living. Like Peretz before him, Sutzkever never ceased to innovate, to master new genres. Like Peretz, he gravitated toward the young—from the time he himself belonged to “Young Vilna” (1929-42), the most promising group of poets, prose writers, and artists who thought to take the Yiddish world by storm, to October 1951, when he called “Young Israel” into being on Kibbutz Yagur, seven Yiddish poets and four prose writers, mostly in their 20s, who refused to change their names and their allegiance to Yiddish. Sutzkever launched their collective presence in the pages of Di goldene keyt before they had the resources to put out their own little magazine and launch their own book series. Their youngest member, the Philadelphia-born Rukhl Fishman, who had apprenticed under Hefetz-Tussman in California before making aliyah, would routinely spend her few days off from Kibbutz Beit Alpha to sit with Sutzkever in his favorite Tel Aviv café as he honed her spare modernist lyrics to perfection.

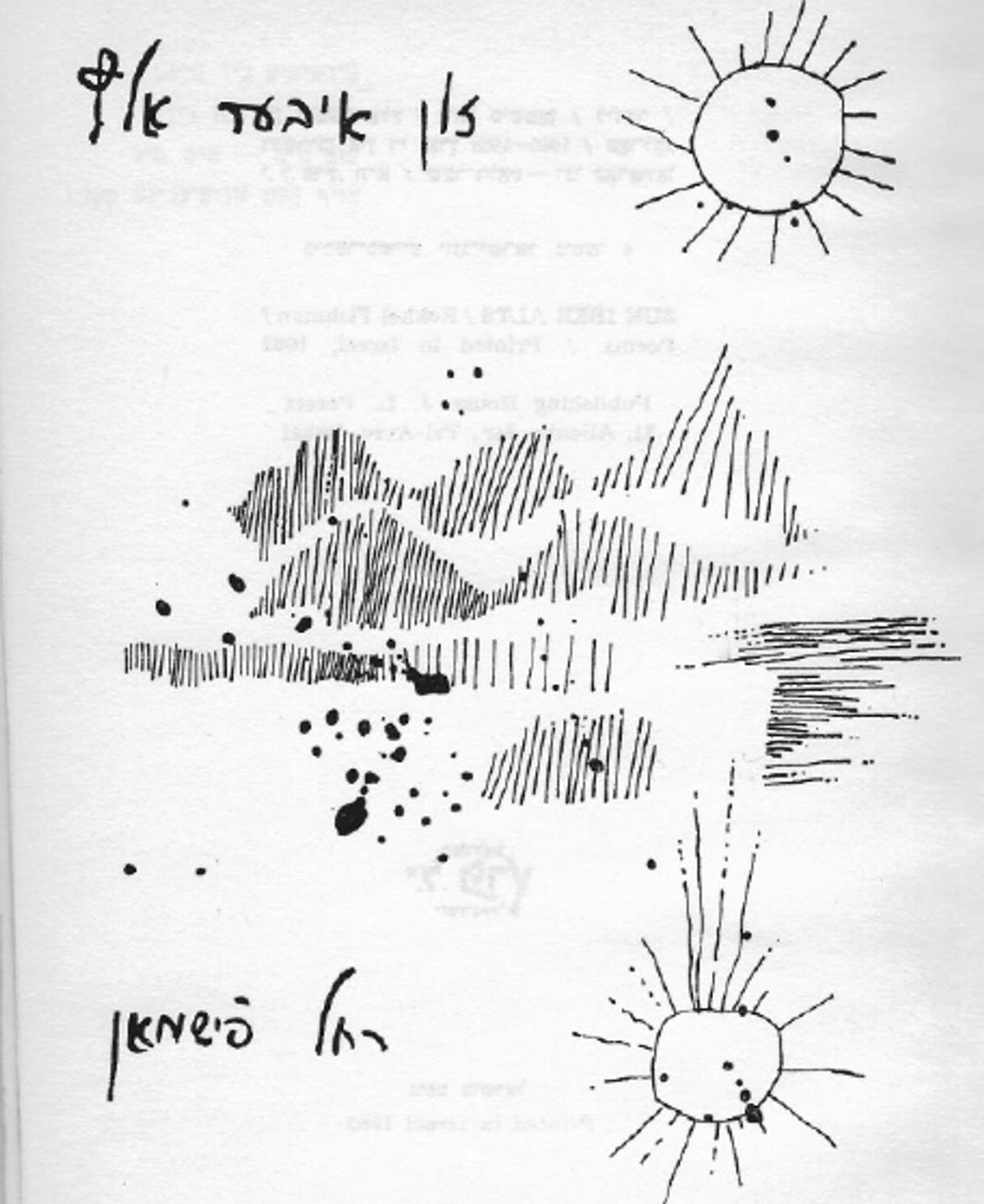

So long as it was in service of the muse there was good reason for a Yiddishist to spend time at the beach. Here, providentially, Fishman was accompanied by fellow kibbutznik, Dani Karavan, who drew a minimalist cover design for her inaugural book of poems. Vertical and a few horizontal lines signified the dunes and the sandy beach; two circles, one in the sky and another, its reflection, signified the sea—viewed not from the land looking out but from the sea looking in. In class we read “Yam mikh arum” (Ocean embrace me), where in seven short lines everything was activated and personalized—the ocean, the waves, the sand—or onomatopoetically mimicked. With memory “roaring” in the sea shell from which a certain voice, as lasting and luminous as a pearl, could be heard, the exuberant use of invented verbs translated into an Israeli Yiddish love song.

Avrom Rinzler was the group’s arch-modernist. Invoking the 13th-century German Jewish poet Süßkind von Trimberg, he referred to the Holy Land as “Terra Sancta”; only as heir to a Yiddish literary tradition going at least as far back as Glikl of Hameln, Rinzler stood on more familiar ground—“Terra Sancta, rokhinkes mit Manger / iber ale dayne zamdn” (Terra Sancta, raisins and Manger / over all your sands.”

Once upon a time, in the heyday of Jewish cosmopolitanism, modernist poets delighted in bringing together the most disparate realms. But thanks to Sutzkever, Yiddish modernism had now come home, and a homegrown modernism could achieve the same surprising effect by yoking together two not-so-disparate Jewish realms. Rozhinkes mit mandlen were, of course, the raisins and almonds of Yiddish lullaby, and Itzik Manger was a modern Yiddish troubadour, still very much alive, who would soon lavish praise on this group of youngsters and on Rinzler, in particular. What was the Holy Land, if not an ancient desert where the folk, the folk poet and his modernist bard all came back to life? What was Israel if not the grandest and most brilliant modernist project of all time?

David G. Roskies is the Sol and Evelyn Henkind Chair emeritus in Yiddish Literature and Culture and a professor emeritus of Jewish literature at the Jewish Theological Seminary.