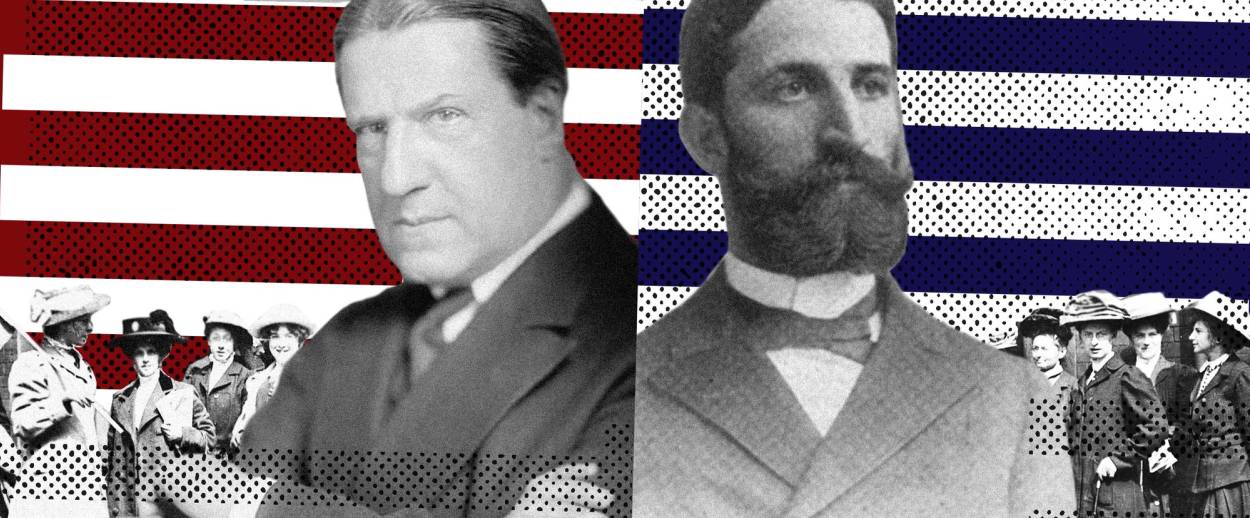

A century ago this month, two of the country’s most prominent rabbis scrapped like a couple of roosters “who ought to have their heads chopped off” over the right of women to vote. At the time of their showdown, Rabbi Joseph Silverman of New York City’s Temple Emanu-El, the flagship congregation of all of Reform Judaism, was as outspoken a foe of the campaign for women’s suffrage as Rabbi Stephen S. Wise was its champion. Personality, principles, and the politics of the pulpit were the actual sources of their enmity, however, in a rivalry that stretched back at least a dozen years. All the same, their clash has special resonance this year, as New York, along with Michigan, Oklahoma, and South Dakota, commemorate the 100th anniversary of the change in their state constitutions that extended the franchise to “every citizen.”

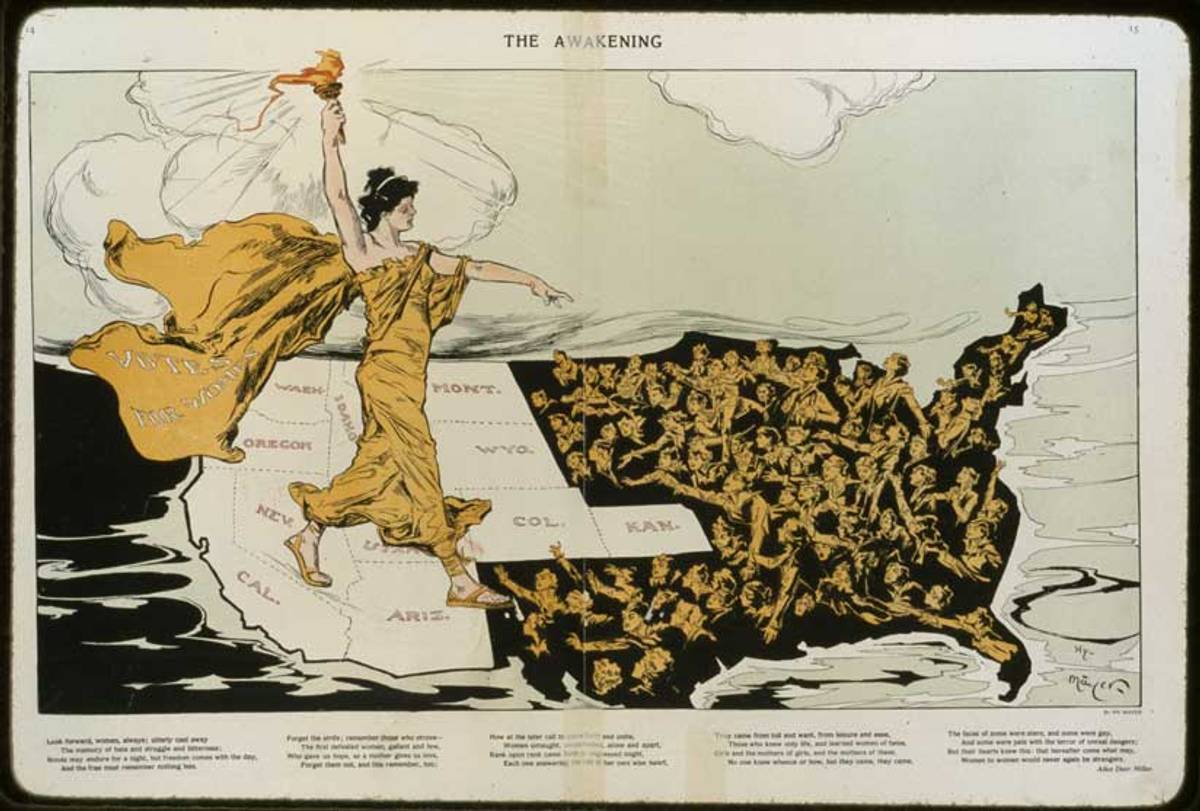

Wise and Silverman are part of the little-known women’s history that is men’s history, too. As civic-minded New Yorkers, as major religious leaders, as men, and as voters with significant followings in the Jewish community, they became key figures on opposing sides in the last lap of the suffrage movement’s uphill struggle. New York in 1917 was the Gettysburg of the suffrage campaign, as a Washington Post editorial put it. “Let the women win New York and the war is over. Let them lose and they will be set back 10 years.”

Nine years earlier, in 1908, Wise became a founder of the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage, along with Oswald Garrison Villard, editor and publisher of the New York Evening Post and the Nation; the philanthropist George Foster Peabody; the philosopher John Dewey, and Dewey’s protégé at Columbia University, Max Eastman, who soon became editor of The Masses. The League, from its 150 initial charter signatories, expanded over three years into a membership of thousands across 35 states. They spoke, wrote, published, marched, acted, danced, and worked the streets. They lobbied legislators, governors, and presidents, and recruited their influential contacts. Within the women’s movement, they served as valued allies.

Silverman was at first forthright—precocious, even—in his support for the women’s cause. “The cornerstone of all kinds of rights for women is the right of suffrage,” he intoned from his pulpit at Temple Emanu-El, in an April 8, 1894, sermon that made The New York Times. Yet not two years later, in February 1896, the American Hebrew reported that he hosted Annie Nathan Meyer as she railed against the suffragists at a meeting of the National Council of Jewish Women and scoffed that American wives, mothers, daughters, and sisters already had plenty of political influence through the men in their lives, and rebuked any mother who would abandon her children’s care to “strange, uncultured servants” in favor of such “trivial social concerns.”

‘The Awakening’ by Henry Mayer, from PUCK, map of women’s suffrage in the United States as of February 1915. (Library of Congress)

Had Meyer’s arguments persuaded Silverman to make such a sharp about-face? Or could it have been a waft of censure from the temple’s powerful board still lingering from that April 1894 sermon? The record gives no indication, but eight months after Meyer’s speech, in November of 1896, Silverman had clearly reversed course. “Woman’s place is not on the farm or at the forge, in the court or counting house,” he now told Emanu-El’s congregants. “She is not fitted for a soldier or a statesman, has no place on the battlefield or at the ballot box. Her place is where the spirit of love alone holds sway.”

Silverman had come to New York from his home state of Texas in 1888 at age 27 to become second-in-command to the temple’s eminent senior rabbi, Gustav Gottheil, who served the congregation until his retirement in 1895. At the changing of the guard, however, the board did not grant Silverman the status of chief rabbi. He remained without full promotion or a full-time co-officiant for 11 years.

The search for a second rabbi intensified after Gottheil’s death in 1903. Wise was a rising star among Reform rabbis and a strong contender for the opening. A New Yorker since his youth, he had been an associate rabbi at B’nai Jeshurun before heading west to become the chief rabbi of Temple Beth El in Portland, Oregon, where he flourished. Wise preached his audition sermon to Emanu-El’s congregants on Nov. 26, 1905, and, as his biographer, Melvin I. Urofsky recounts, the board was keen enough to initiate negotiations with him before he left town.

At the meeting, Wise set down a slew of conditions to which the board indicated agreement, even if they raised eyebrows. Then came his deal-breaker, one he knew would run counter to a long-standing board policy. He asked for assurance that the pulpit be free. The board secretary, Louis Marshall, countered that the pulpit must remain under board control. This was abhorrent to Wise, the seventh in an unbroken generational line of rabbis, who fully expected to continue to use his pulpit as a platform for advancing civic and social reform. He requested a letter of clarification, which Marshall duly sent. Quietly, several board members urged Wise to accept the position regardless. Never in half a century had the board muzzled an Emanu-El rabbi, they argued. Would the great Rabbi Gottheil have stayed so long otherwise?

In a short letter of reply to Marshall, Wise withdrew himself from consideration. No “self-respecting minister of religion,” he wrote, would accept such control. Wise followed up his reply, with its implicit criticism of Silverman, in a lengthy open missive to Emanu-El’s membership which, before its intended recipients received it, he read aloud to his Portland congregation and released to the press. “A free pulpit will sometimes stumble into error,” Wise’s letter read, but “a pulpit that is not free can never powerfully plead for the truth and righteousness.”

The New York Times devoted three columns to the brouhaha in the next day’s newspaper, quoting both Wise’s and Marshall’s letters in full and adding a short statement from Silverman and longer comment from Marshall and the board president, M.H. Moses. All three disingenuously insisted that no offer had yet been made to Wise or to anyone else. Marshall reproached Wise in print for making public a “private and unofficial conversation, tentative in character, and essentially confidential in nature.”

Wise moved back to New York all the same, certainly not to serve Emanu-El but to found in 1907 the congregation known eponymously today as the Stephen Wise Free Synagogue. Five months later, Emanu-El’s board named 29-year-old Judah Leon Magnes of Brooklyn’s Temple Israel “co-associate” rabbi with Silverman, now 45. It took only a year for Magnes to run afoul of both Silverman and the board over a controversial sermon and for a second time at Passover in 1909. The board declined to renew Magnes’ contract and did not name a successor for another six years.

Wise, meanwhile, immersed himself in the life of his young congregation; in wider Jewish, interfaith, city, state, and national affairs; and in a dizzying array of progressive, humanitarian, and civil-rights causes. By this point, Wise was advocating regularly for women’s suffrage and Silverman just as avidly against. Wise advanced the still-favored argument that women’s rights are human rights and that America could not truly call itself democracy until women had the ballot. Silverman countered that the only natural roles for women were homemaker and educator of children, adding as a warning that if equal suffrage ever came to pass, it would need to mean equal military and police service “irrespective of sex,” too.

Despite such pronounced differences, there were plenty of reasons for the Reform rabbis of the East Coast to find common cause, as they did at Wise’s home on April 22, 1912—Silverman included. Together with 19 other mostly East Coast colleagues, they formed the Eastern Council of Reform Rabbis, a perceived power grab that caused no end of hand-wringing on the part of the much larger, long-established CCAR, the Central Council of American Rabbis. Several known suffragists were among the Eastern Council’s original signatories, including Rabbi Emil G. Hirsch of the Chicago Sinai Congregation, who, as early as 1905, traveled to Portland to address a national conference of the main suffragist body, the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Others among them were Rabbi Theodore Joseph of the Third Street Temple in Troy, New York, who was a charter member of the Men’s League; and Rabbi Maurice Harris of Temple Israel, who Wise strongly favored to be Eastern Council’s first president against some “poor and sorry pleading” from Rabbi Rudolph Grossman of Rodeph Shalom, who pushed hard for Silverman to get the honor as his 25th anniversary at Emanu-El neared.

The notion of Silverman in the role filled Wise with scorn, especially after Silverman made his own plea for the post. Wise’s diary entry of May 9, 1912, drips with contempt: “Dr. Silverman called this morning and never on land or sea was there such hemming and hawing as took place in my study during the honoring visit of the rabbi of Temple Emanuel, whose place I so terribly covet and grieve not to have secured.” Silverman, he wrote, felt that his prestige and the temple’s were being used to give the council clout and that he was not going to play second fiddle to anyone. “I tried to make clear to him in serenest terms that no position, however important, could add to his own stature,” Wise went on, “and that surely he felt as I did, that neither of us cared for any office.” He added that he found “very sorry and pitiable his begging me for a position for which he is not fit.”

Wise was reluctantly willing to accept Silverman as president at some later point, but “he must not be the first. We need a strong and militant leadership and no one would dream of that from him. I told him he ought to be the first vice-president, and I fancy he is half inclined to accept that …”

Such interplay with his colleagues always left Wise with a severe attack of “rabbiphobia,” he told his diary. Five days later, he relented. Silverman was named vice president “with a view to his taking Harris’s place at the close of the year.” In another sarcastic entry, Wise added, “My spirits were cheered and uplifted today by the joy of high intercourse with my colleagues of the Eastern Council. Nothing is quite as ennobling as one of those sessions with my brothers in the ministry, especially Silverman, who seems to use the Council as an advertising scheme.”

Twice, in 1913 and again in 1915, the CCAR hedged on the women’s suffrage question with a timid sidestep away from collective action. It called on Reform rabbis “individually and in their pulpits, and through their ministry” to advocate for the cause. (As early as 1889, the CCAR had called for full voting and membership privileges for women in its congregations, but the measure lay dormant, unreinforced until its reaffirmation 85 years later, in 1974.)

By April of 1917, with New York State’s make-or-break vote just ahead in November, Wise began to push hard for the Eastern Council to pass a pro-suffrage resolution. He knew well, given the failure of a previous state referendum on the question in 1915, how much a victory in New York would mean to the movement overall. Publicity from the endorsement of a major religious body could carry weight with New York’s Jewish voters, who, like their rabbis, all were men.

At the time, Wise was still popular on the pro-suffrage lecture circuit. A surviving recording of his “Women and Democracy” speech is typical. Silverman, meanwhile, was being widely featured in newspapers across the state among “Famous Men Opposed to Granting of Votes to Women.” His name and words appear in a publicity release reprinted dozens of times in local New York State newspapers from Bolivar to Bath to Belmont to Buffalo, and in an anti-suffrage ad that had wide placement.

On April 23, 1917, the Eastern Council convened in its regular quarterly session with Silverman presiding. Wise, no doubt anticipating the reaction to come, introduced a resolution in favor of women’s suffrage and led the debate, expressing his deep regret that Jews seemed always to hesitate when it came to backing a crucial social cause. Silverman tried to stop the resolution from coming to a vote, accusing Wise of disruptive sophistry for twisting a political issue into a moral one. Too few American women even wanted the franchise, Silverman argued, later adding that the timing was wrong, with the United States entering World War I. Wise threatened to resign over the accusation of sophistry, which led Rabbi Isaac Moses of Temple Ahawath Chesed to level the “scrapping rooster” smack-down, which the Times gleefully quoted.

In the end, Wise prevailed. The resolution passed. Wise did not go to the luncheon that followed. Silverman assured the assemblage that Wise’s absence had no underlying meaning. There was absolutely no fight between them. They were and remained “ friends of longstanding.”

The Eastern Council’s action prepared the way for the CCAR to pass a pro-suffrage resolution of its own that July, unequivocal this time: “As ethical leaders and as preachers of a religion which has stood throughout the centuries for justice and righteousness to assert our belief in the justice and righteousness of the enfranchisement of the women of our country.” In fact, by 1917, popular sentiment in favor of the women’s campaign had grown wide enough to make the rabbis’ move an uncontroversial one. By 1919, even an Orthodox scholar, Rabbi Jacob Levinson, issued a monograph offering a halakhic case for supporting women’s suffrage.

The great New York State referendum victory of Nov. 6, 1917 broke the hex that had bedeviled the suffrage movement until then in all states east of the wide Missouri River. More states followed and support for federal action got its energizing boost.

As for Wise and Silverman, life went on much as it had. Silverman died first, on July 26, 1930. He had served Emanu-El for 34 years and as its rabbi emeritus for eight. Some 1,200 mourners filled the sanctuary for his funeral. His coffin received the “exceptional honor” of placement in the chancel, directly in front of the Ark. The eulogy was respectful. “He came to see, as had seen a great teacher of Emanu-El before him, Gustav Gottheil—that back of every phase of Judaism—orthodox, conservative or reform—stands the eternal Jewish people.” And the headline in the Times focused on the eulogist ahead of the deceased.

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.