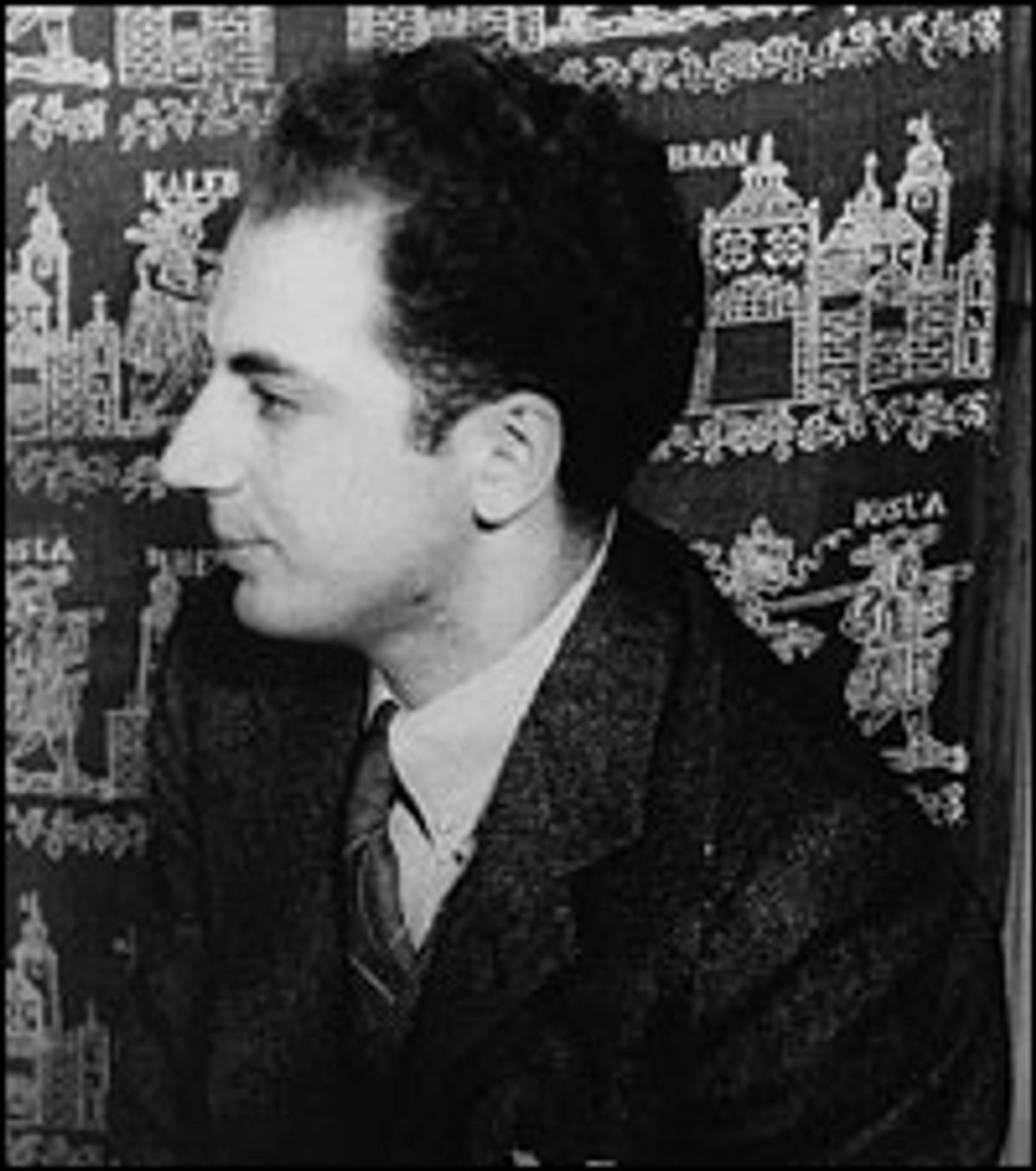

Clifford Odets is generally considered to be a great talent of his time, rather than for all times, and his works are not revived nearly so often as those of Tennessee Williams, Eugene O’Neill, or Arthur Miller. But this month, Lincoln Center Theater is restaging Odets’ Awake And Sing!, at the Belasco, the Broadway house where it was originally produced in 1935. The play follows the Bergers, a lower middle-class Jewish family living too close together in the Bronx, and addresses what the author called “a struggle for life amidst petty conditions.” Their conflicting desires set one generation against the next: a smart-aleck sister in trouble, a restless younger brother, a passive father, a wise but broken grandfather, and Bessie, a mother ready to mock, trick, or bully them all into submission.

They are a Jewish American nightmare, these Bergers, real enough to make a reader flinch. Their niggling fears are all on the surface, exposed like cockroaches under a sink: eviction, starvation, shame. Bessie’s worldview is all the more frightening because even when her actions are despicable, her logic is sound: “Here without a dollar you don’t look the world in the eye. Talk from now to next year—this is life in America.”

Odets’ actor-collaborators at the two-year-old Group Theatre initially rejected the play, finding the Bergers not so much embattled as flat-out coarse. Odets had tailored the script, originally called I Got the Blues, to members of the Group with whom he worked and sometimes lived, but they nonetheless objected to its “rather gross Jewish humor” and “messy kitchen sink naturalism.” Two years later, when another producer wanted the play and the Group Theatre was desperate for material (and probably worried about losing all those good parts), they agreed to mount a revised version, with fewer Yiddish references and a more hopeful title, after Isaiah 26:19, “Awake and sing, ye that dwell in dust.”

By the time Awake and Sing! opened, Odets had rocketed from junior-level actor to the Group Theatre’s primary voice. His Waiting for Lefty, in which a taxi strike heralds revolution, caused a populist sensation, sparking a 45-minute curtain call on opening night, January 5, 1935. Even so, the Group had a hard time raising the money for Awake and Sing! and was able to produce the play only because of a steady stream of profits from Lefty, which continued to run in New York and spread to more than 60 cities within a year. Awake and Sing! was respectably but tentatively reviewed in 1935, then lauded as an American classic upon its revival as part of the Group’s repertory in 1939.

What happened in four years to change the reception of this story about a Jewish family whose moral values are all but lost in the clutches of life in the Bronx? It may have been Odets’ new prominence (he made the cover of Time in December of 1938) that caused a critic such as Brooks Atkinson to revise his opinion of the play. Or perhaps the shift from the Depression into wartime allowed the audience some distance from the circumstances of the Bergers’ lives. I suspect, too, that the play’s Jewish focus, disquieting in 1935 when Yiddishkeit was not often seen uptown, might have seemed more sympathetic, moving, or at least intriguing to audiences by 1939.

At the crux of Awake and Sing! is a premise that people get twisted away from their destinies by the conditions of their lives, that poverty blocks the soul. This suggests a different reality, and even a different aesthetic stance, from the dramas of Odets’ immediate predecessor Eugene O’Neill. O’Neill’s heroes tend to be romantics or addicts who refuse to allow facts to change who they are, even when that denial leads to madness or death. A decade after Odets, Tennessee Williams, too, would wring tragedy from delusion. In fact, most great American central characters insist on a haze that suffuses the plays themselves: Blanche’s dim lighting, or the morphine twilight of Long Day’s Journey Into Night.

By contrast, the Bergers operate cold sober. Even the fierce idealism that Jacob imparts to his grandson Ralph is rooted in a hard look at Jacob’s own failings: “Do what is in your heart and you carry in yourself a revolution. But you should act. Not like me. A man who had golden opportunities but drank instead a glass tea.”

Ralph, “a boy with a clean spirit,” yearns for a pair of black-and-white shoes, his own bedroom, and a chance to fix his teeth. He takes up his grandfather’s worldview, but only the Marxist part, ignoring the biblical foundations that support the title line. It seems that Jacob’s Hebrew and religious learning will die with him, as no one in the family reacts to his blessings or quotes. Ralph instead hears Jacob’s plea to make a world in which poor people can control their fates, a world in which “life isn’t printed on dollar bills.”

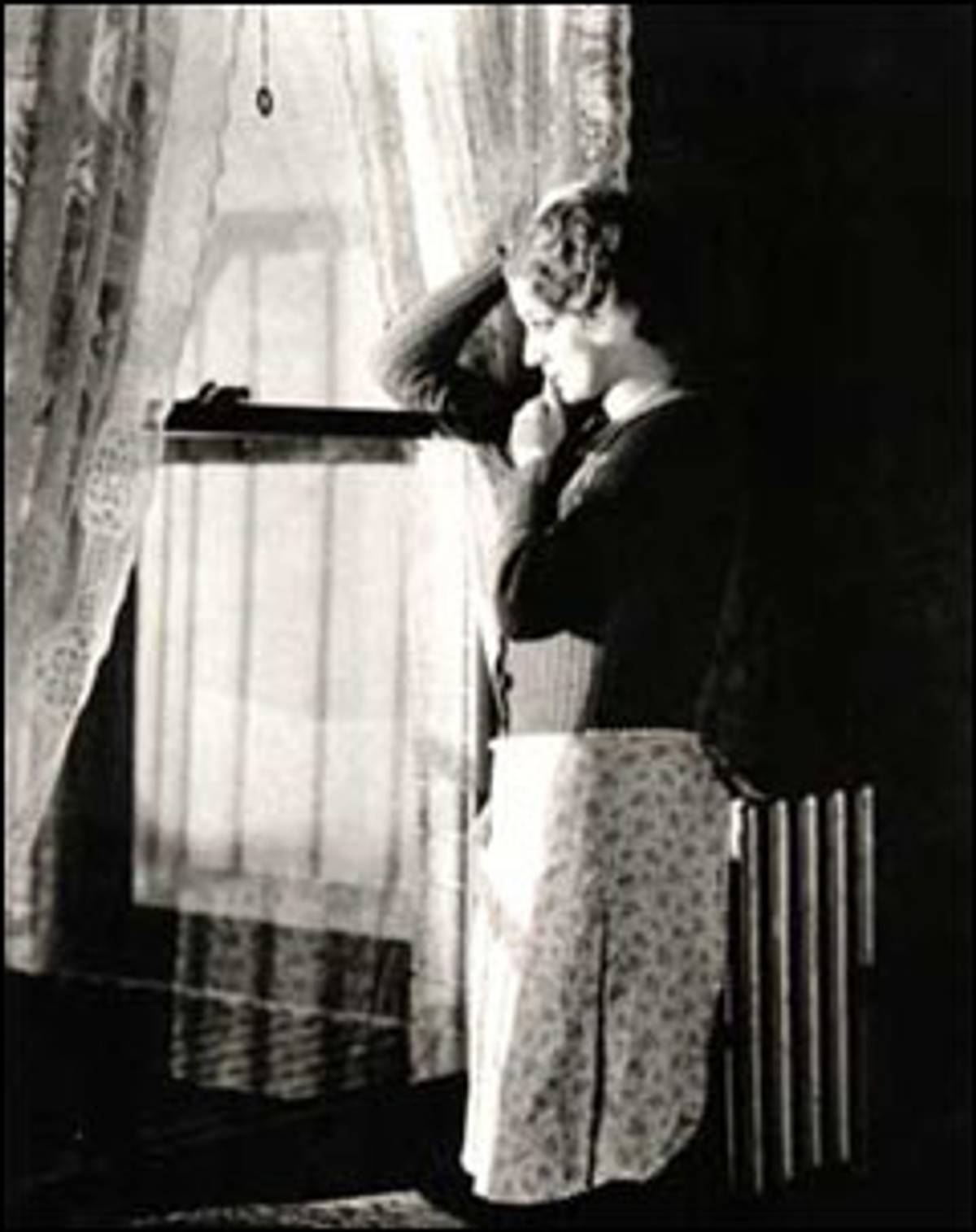

The people in Awake and Sing! need money. They need it badly. They live crammed together, and familiarity makes them vicious. They scrabble; they scrape; they cheat. They con one another out of coins, favors, and track winnings. They are dishonest, unhappy, and sometimes cruel. They wield whatever power they have with as much grit as they can muster, which is a lot. Bessie, the matriarch who claims, “Here I’m not only the mother but also the father,” is the hardest-edged and sharpest-eyed of all.

Odets describes Bessie one way and dramatizes her another. He writes, “She is constantly arranging and taking care of her family,” a generous gloss on such measures as pawning off her pregnant daughter in marriage to an unsuspecting immigrant. Bessie intercepts calls from Ralph’s girlfriend and then lies about it, because she counts on Ralph’s $16-a-week salary and doesn’t want him to marry. When Ralph confronts her, Bessie reverts to the popular Jewish grammatical tense my father used to call the Third Person Invisible:

BESSIE: A girl like that he wants to marry. A skinny consumptive-looking…. You should see her. In a year she’s dead on his hands.

RALPH: You’d cut her throat if you could.

BESSIE: That’s right! Before I’d ruin a nice boy’s life I would first go to prison.

The author tells us that Bessie “loves life, likes to laugh, has great resourcefulness and enjoys living from day to day.” It’s a kind appraisal of a woman who schemes to cheat her own son out of his grandfather’s insurance money.

The difference between how Odets sees Bessie and what she actually does suggests that the person in the opening description has been warped by the plotline of her own life. In another situation, maybe Bessie Berger would seem to love life, and maybe we’d even hear her laugh. But on Longwood Avenue she is a small-time hustler in her own home, steering the family’s narrow course between destitution and outright crime. Her husband, Myron, a dopey store clerk whom Bessie once tried to put through law school, is sweet but no patriarch. Her tycoon brother, Morty, isn’t offering any handouts and in fact literally eats up the family’s resources on his rare visits, when Bessie cooks budget-busting meals that nonetheless fail to meet his millionaire standards:

BESSIE: The best Long Island duck.

MORTY: I like goose.

BESSIE: A duck is just like a goose, only better.

Will Bessie Berger seem softer now, at Odets’ centenary, 70 years after Stella Adler originated the role? Will she be harder to digest, or easier to dismiss? Will Lincoln Center audiences, presumably for the most part a couple generations and a comfortable cushion removed from the Bronx, relax around Bessie, as if hearing a familiar Jewish-mother joke? Or will her blatant grasping and shrill geshray-ing embarrass, a peek into a culture we’d rather forget?

Bessie Berger could emerge as a huge character, potent enough to stand alongside the most important American female roles. Zoë Wanamaker, a reigning British classical actress with New York Russian Jewish roots, seems an inspired choice. In a Broadway season that highlights Mrs. Lovett, the murderously practical purveyor of meat pies in Sweeney Todd, maybe there’s room for a fierce Jewish lady who challenges the American ideal of motherhood because she sees too clearly to be nice.

Odets’ language is wide awake, and it doesn’t sing so much as snap in unflinching staccato, even in the love scenes. Today, I wonder if the urban specificity of his immigrant dialogue, the bare questions about class and opportunity, might land hard and clear for audiences contemplating a torn social safety net and “petty conditions” that seem anything but trivial. Some of Bessie’s fears, allayed by 70 years of New Deal legislation, seem to be coming home to roost.