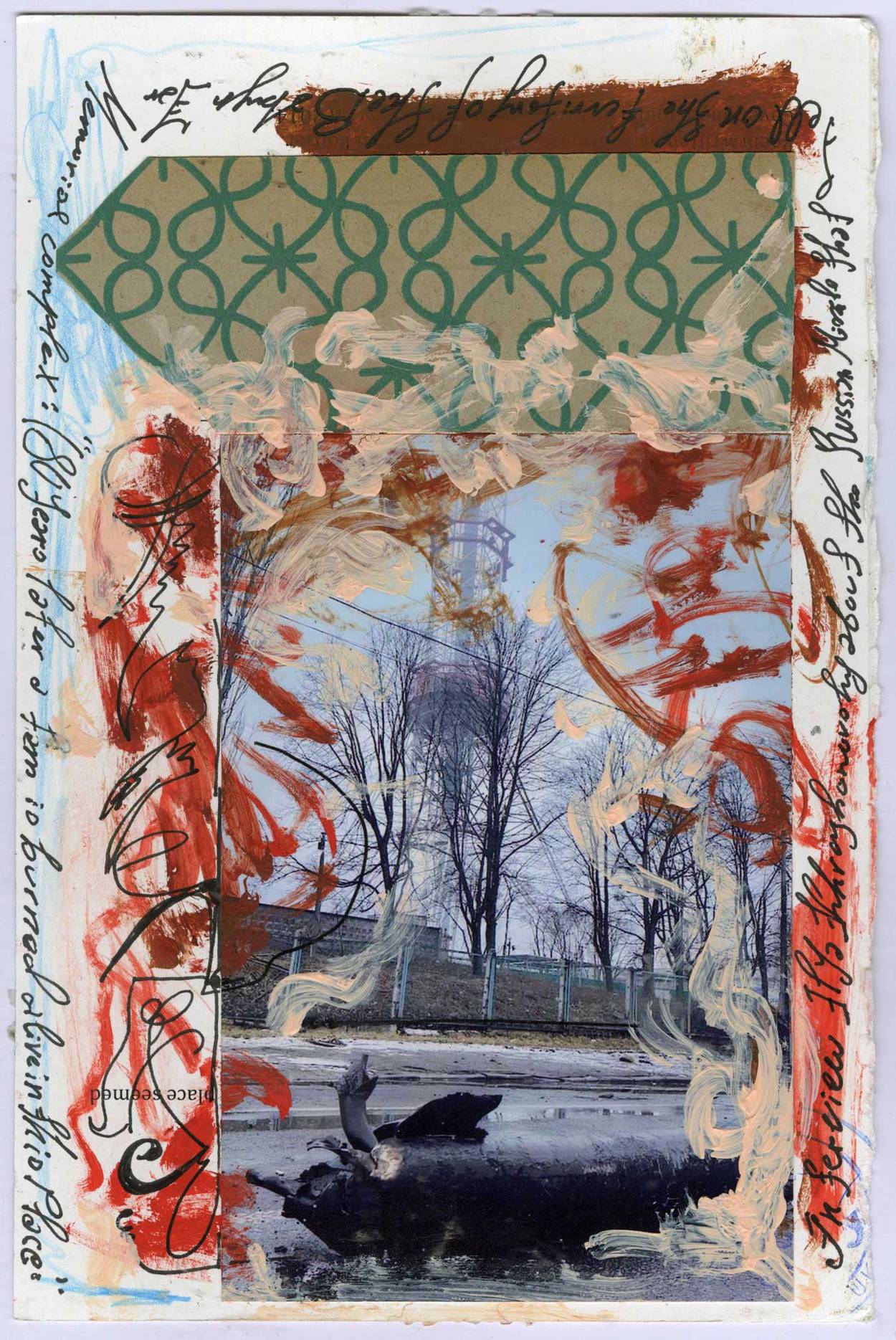

Tablet Writer Vladislav Davidzon Makes Notebooks Into Art in Paris Show

Selections from ‘War and Constraint,’ at the Fondation Fiminco

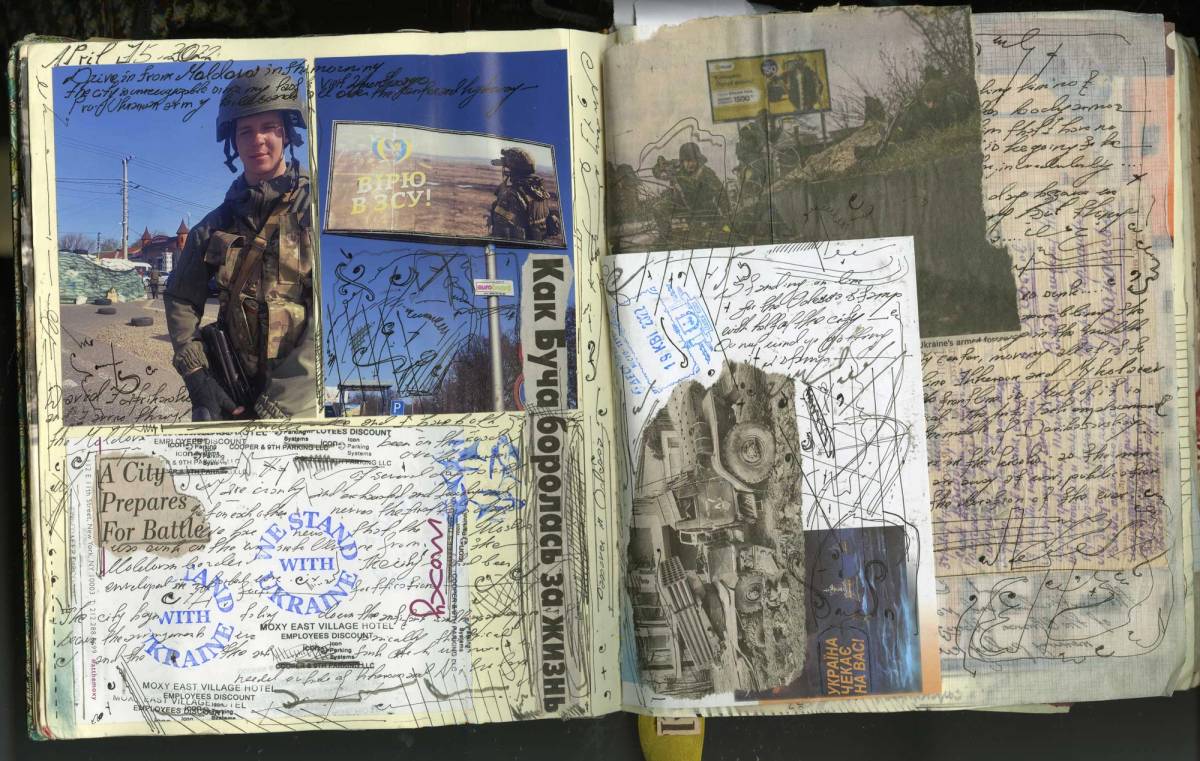

Daybook Page April 15, 2022

Return to Odessa

After evacuating the women and children in my family from Odessa to Europe through Romania, and giving some fundraising speeches in New York to raise money for Ukrainian charity, I arrive back at the Ukrainian border with Moldova. Travel with my intrepid and swashbuckling comrade in arms and fellow Tablet writer—British journalist David Patrikarakos. The highway into the Odessa region is encircled by police and military checkpoints. These are manned by an assortment of young conscripts, mobilized older men and comely Ukrainian policewomen with submachine guns slung low across their backs. Both Patrikarakos and I are in a somewhat irritable mood after having spent many days traveling and reporting. My friend elegantly vetoes my proposal that we pass the time in the car by reading out long sections from the Thomas Pynchon novel that I have brought along with me.

At the Ukrainian border crossing we receive confirmation that the Russian cruiser Moskva has been struck by a pair of Ukrainian R-360 Neptune class antiship missiles. The flagship of the Russian Black Sea fleet is sinking, and this fills the city with glee. The sinking of the flagship—which was also a command and control center for much of the Russian Black Sea operation—will turn out to be a seminal turning point in the war. The sinking instantly relieves the Russian pressure on southern Ukraine, and it is no longer feasible for the Russians to mount a naval assault on Odessa from the sea. Ukrainian naval officers inform me that many of the elite Russian marines who had been stationed aboard the Russian landing craft had mutinied and refused to storm the beaches of the region. Those beaches have now been mined.

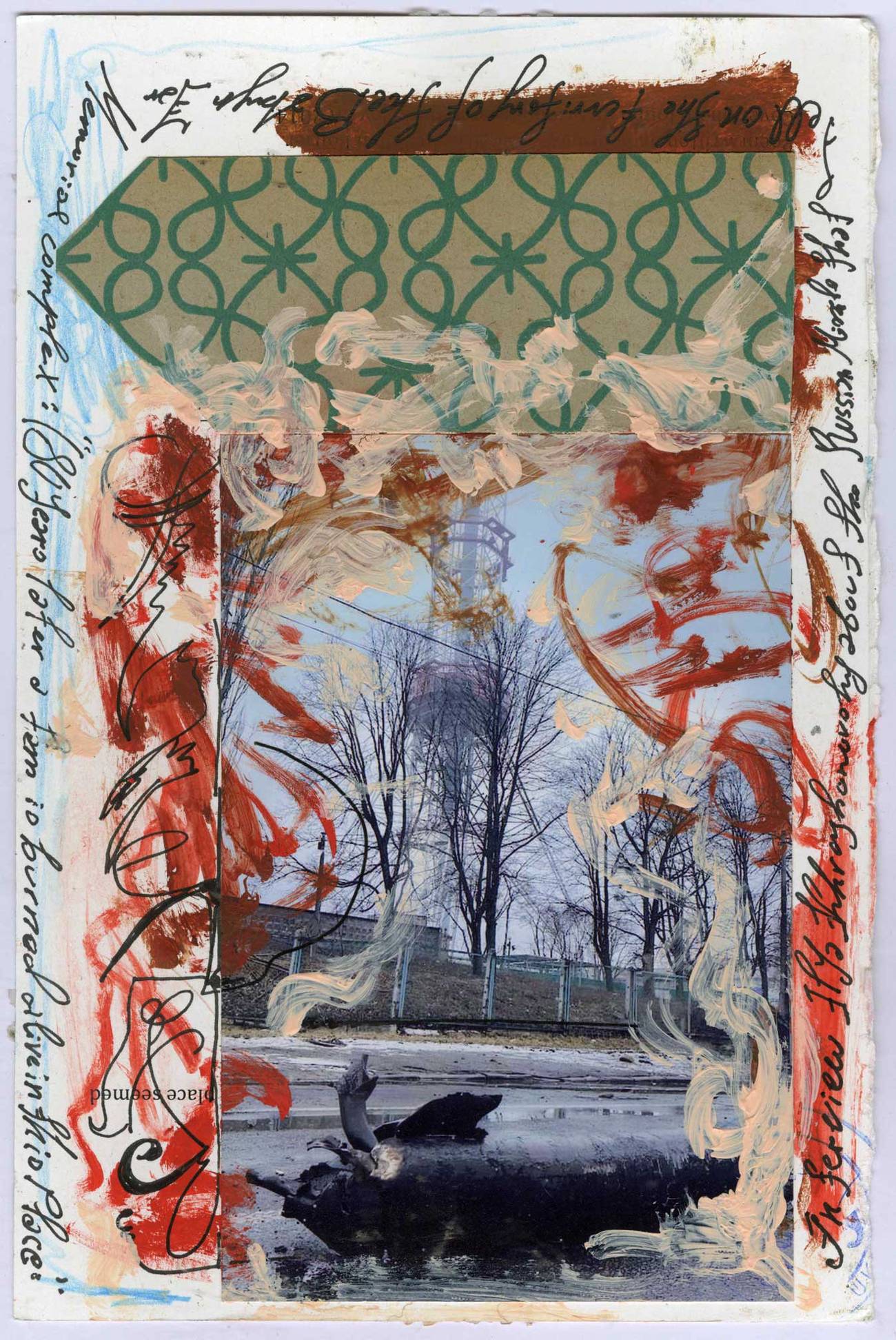

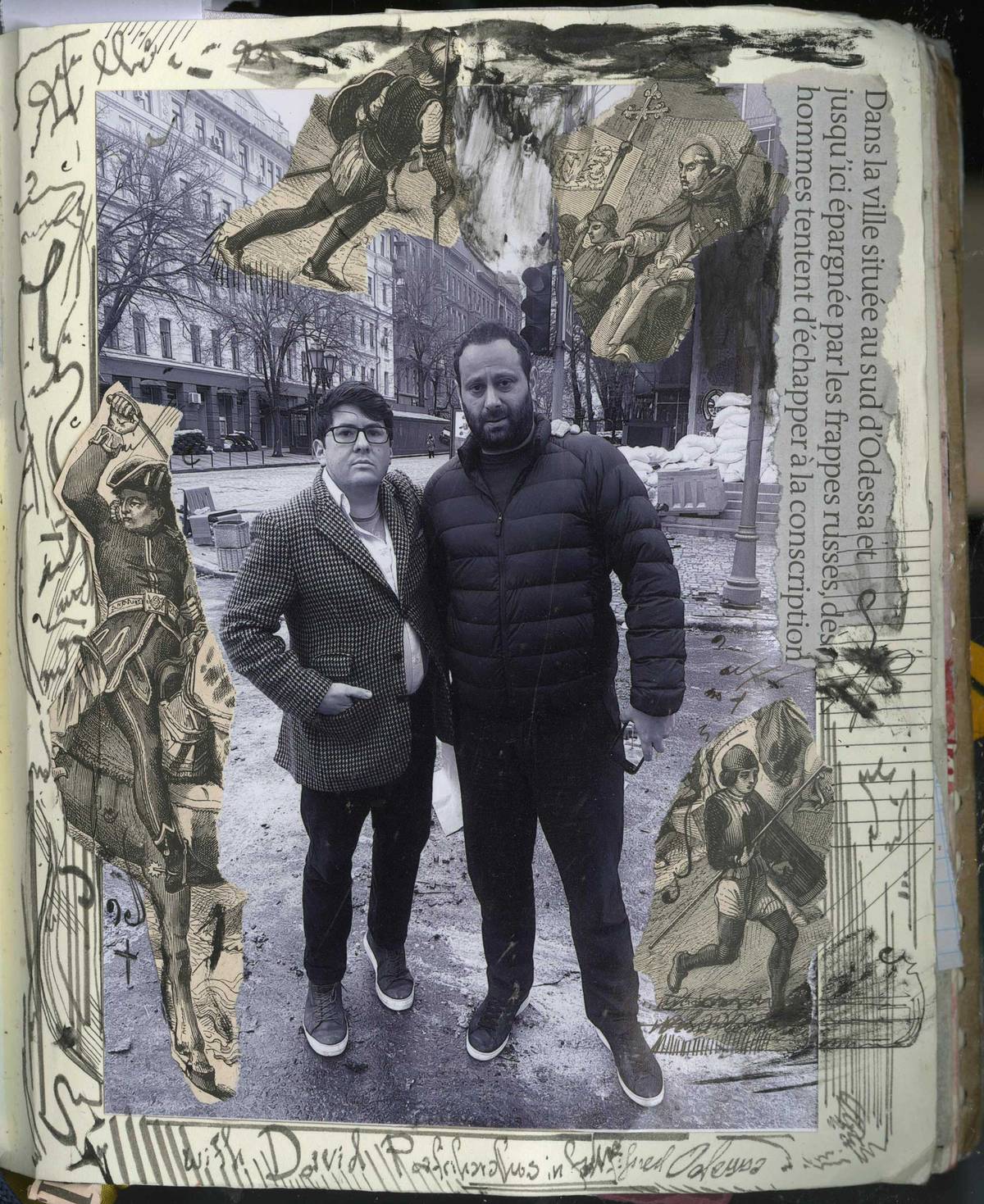

Daybook Page April 17, 2022

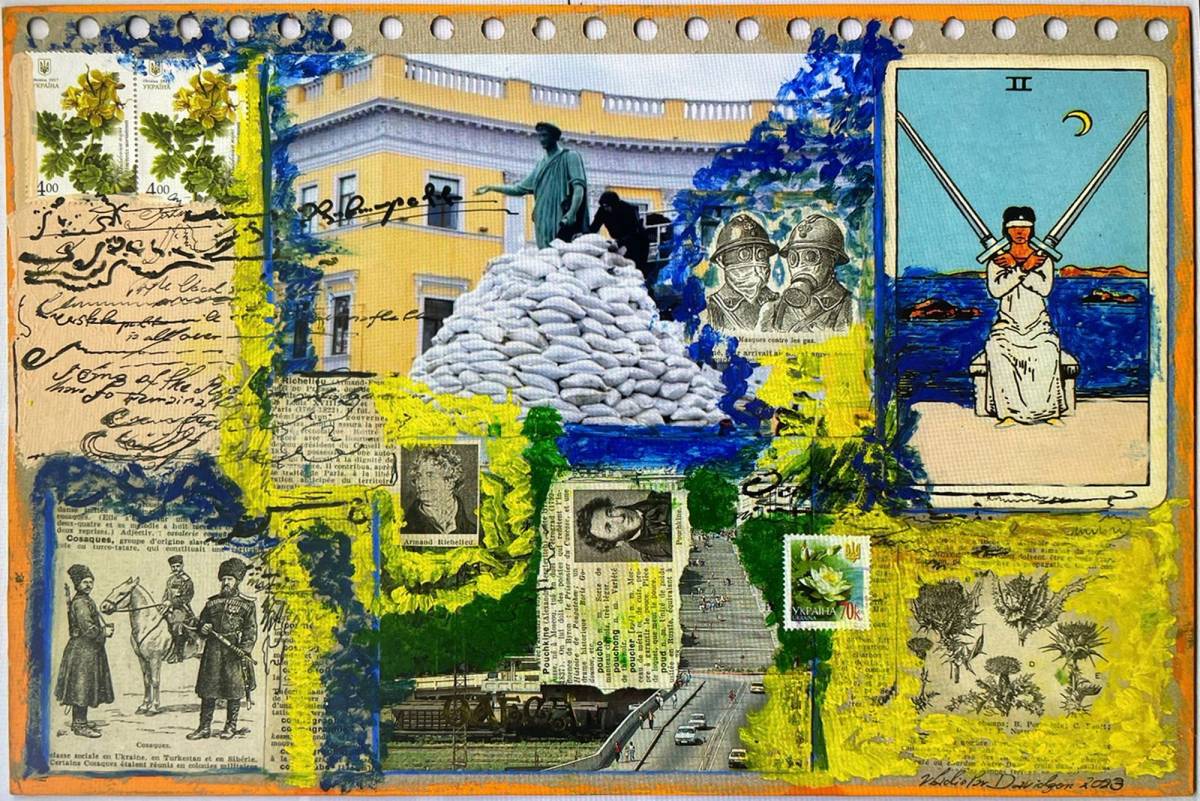

Odessa Under Siege

Patrikarakos and I arrive in the city [Odessa] as the final operatic and floridly theatrical phase of its defense is concluding. The pictures of the opera house and monuments to Pushkin covered in sandbags have been splashed across the front pages of every newspaper in the world. As the city and region are no longer under serious military threat, the authorities began to swiftly disassemble the fortifications, antitank obstacles, and military checkpoints that had enveloped the ravishingly beautiful center of the city. The sandbags and antitank emplacements are duly trucked out east to fortify Ukrainian positions outside of Kherson and Mykolaiv.

Moscow desperately desires the city and considers it to be a core part of their conception of traditional Russian imperial holdings. So they won’t be bombing it in the same manner that they have Mariupol. Mayor Trukhanov has recast himself as a nationalist and has thrown his lot in with the Ukrainian government. He is running around, fierce war paint on, delivering grandiloquent speeches laced with underworld argot. The Russians will not be taking the city.

Patrikarakos and I pose in front of the Deribasovskaya street with our backs to the fortifications. David begins writing what will turn out to be a charming and very moving piece about the city, “Odessa is at war with itself.” It centers around me as the archetypal (that is, mixed and ambivalent) Odessan. He also writes about my blasted war dentistry—after I had lost my front teeth at the start of the war.

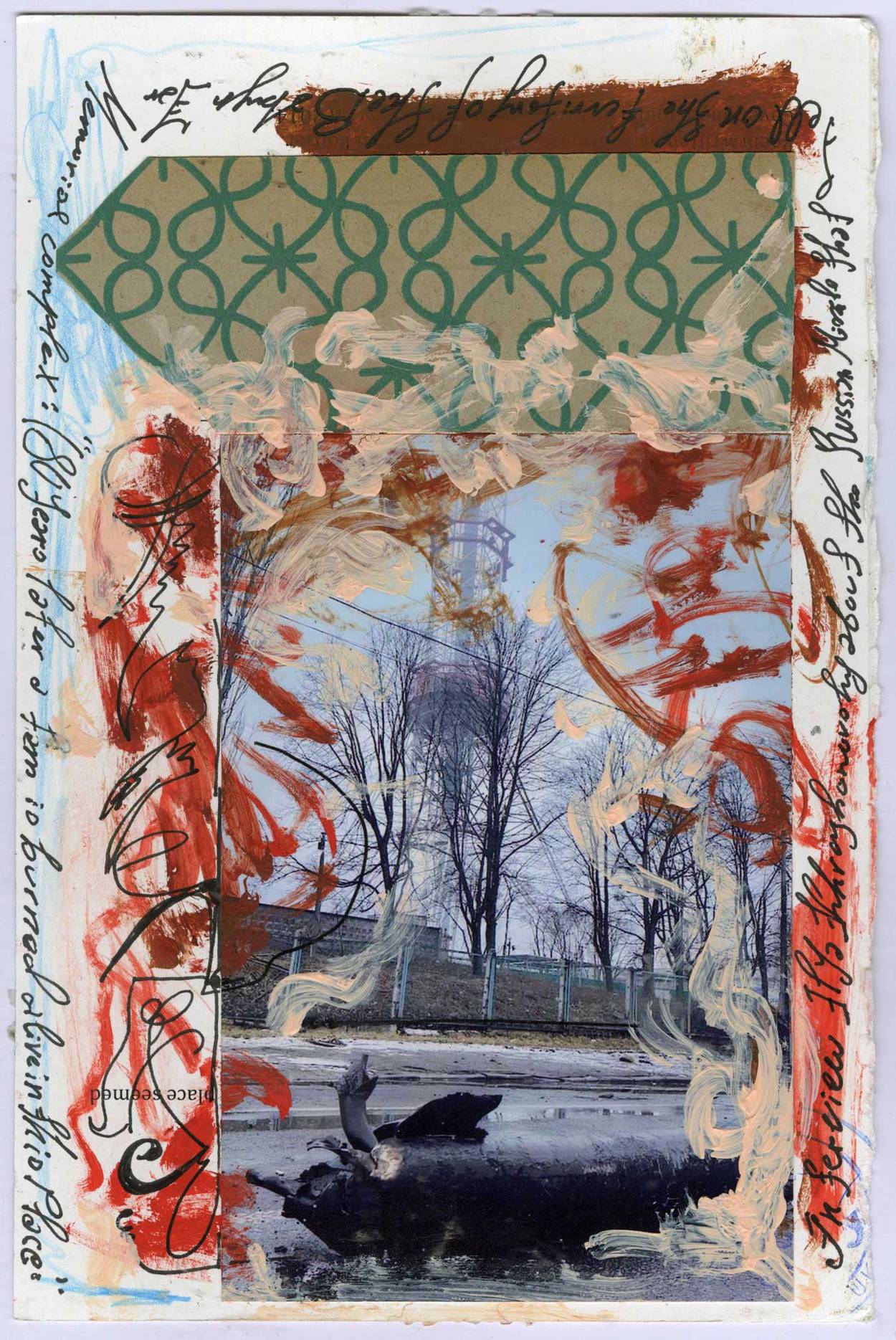

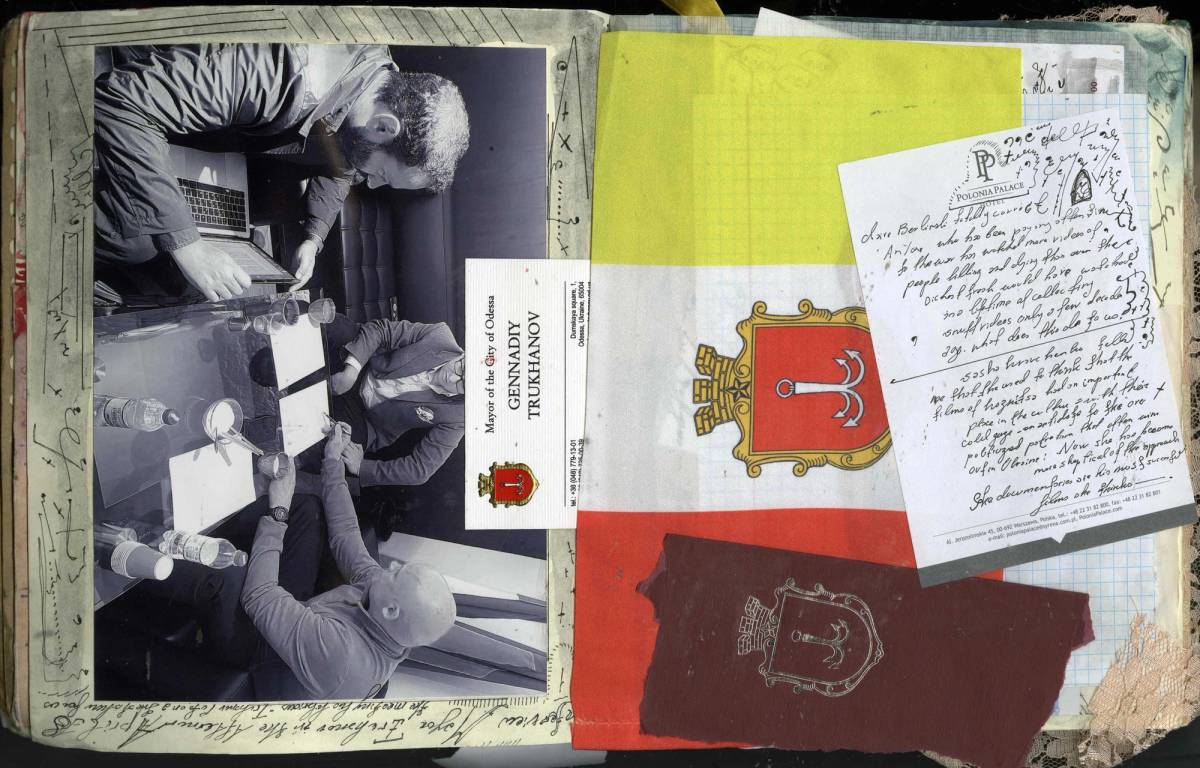

Daybook Page April 18, 2022

The Mayor of Odessa

Mayor Trukhanov is on the warpath. He is also keen to settle the public view of him as a separatist or a mobster. He, however, remains a real hoot to spend time with and does put on a good show for us visiting international journalists. He informs David and me that Odessa is like a beautiful woman to the Russians. That she looks available, but the fact is “that she cannot be forced. The city is like our women, who may look very open and accessible but in fact are proud and loyal.” I almost want to not translate that part for David out of a momentary sense of protectiveness for the wartime leader.

The buff former Soviet artillery officer is keen to show off his military bona fides, and in between taking theatrically staged calls from the generals begins to sketch out the potential battle plans on a piece of paper. He informs us that at the tactical level, there are two main bridges whose destruction would cut the city off from the rest of the country. Odessa will only be taken through a multisided and coordinated arms assault, he informs us—and that is only after Mykolaiv would be overrun. The Russian land forces would have to break through the Ukrainian lines at Mariupol in order to provide cover for an assault from the sea by the Russian marines. The Russian army would have to try to link up with their forces in Transnistria—which remains a threat.

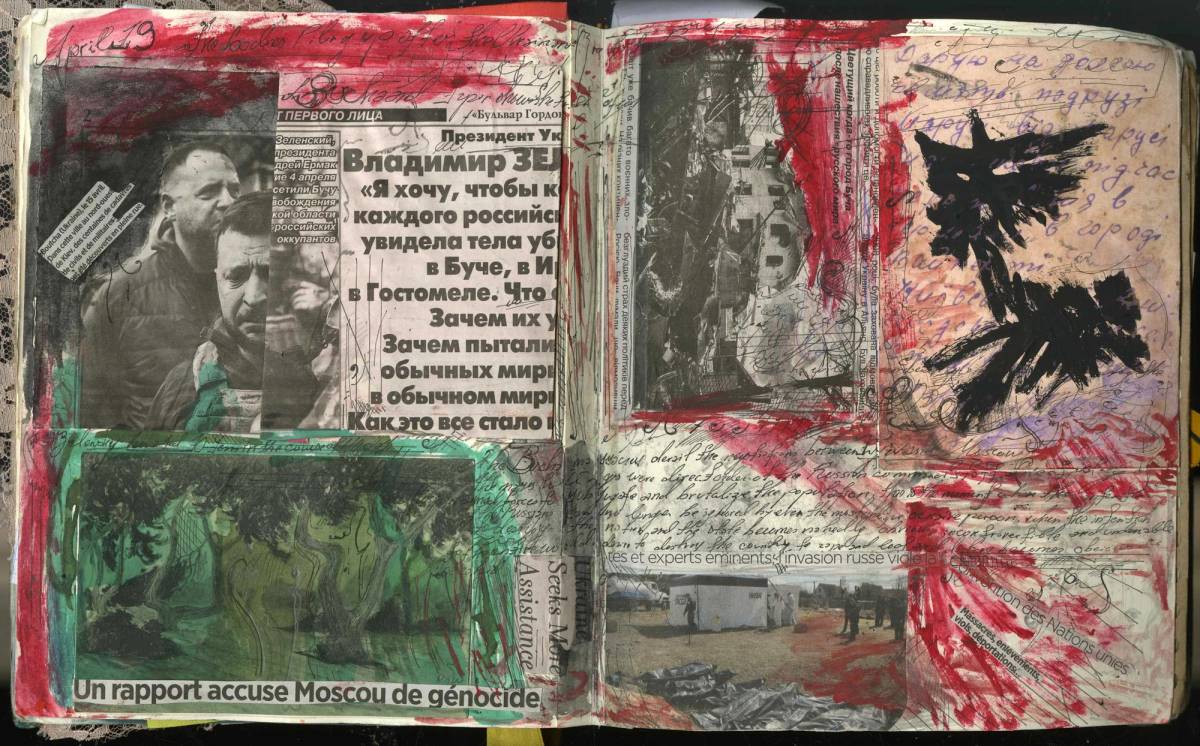

Daybook Page April 19, 2022

Zelensky in Bucha

Zelensky was a pretty boy two months ago. Now, his handsome face is haggard and drawn—the exhausted visage of a man who is processing overwhelming trauma, rage, and hatred that he could never have imagined could be directed at him. He is representative of a large swath of the population, who are quickly learning to hate Russians. So—exhausted, but clearly also learning.

The monstrous scenes of destruction in Bucha ensure that there will be no serious negotiation taking place between Kyiv and Moscow for a very long time to come. The bloodbath in the city—hundreds randomly shot, old people succumbing to heart attacks in their cellars, policemen executed, girls raped, houses pillaged—is unspeakable. I am told that members of the presidential administration have taken to texting photos of the bodies strewn in the roads here to the personal phone numbers of European leaders before asking for more weapons.

My wife, Regina, and I had used to visit the Bukovskys at the dacha that they rented here before the war. It was lovely—located in a secluded, wooded, and discreetly wealthy town full of professionals and young families.

The translator Irina Zaytseva tells our circle that the family house in Bucha was also pillaged and stripped of everything that could be moved. The Russian soldiers tore everything to pieces looking for the valuables. They ate and drank everything, including the medicinal and rubbing alcohol. They left their feces strewn all over the bathroom. The washing machine is gone, naturally—the Russian army is being paid for its acts of cruelty with the piratical right to appropriate washing machines. Yet the barbarians left the most valuable assets in the house—the paintings by Irina’s famous Soviet realist painter grandmother remained on the walls. They simply did not know what it was that they should have been pillaging.

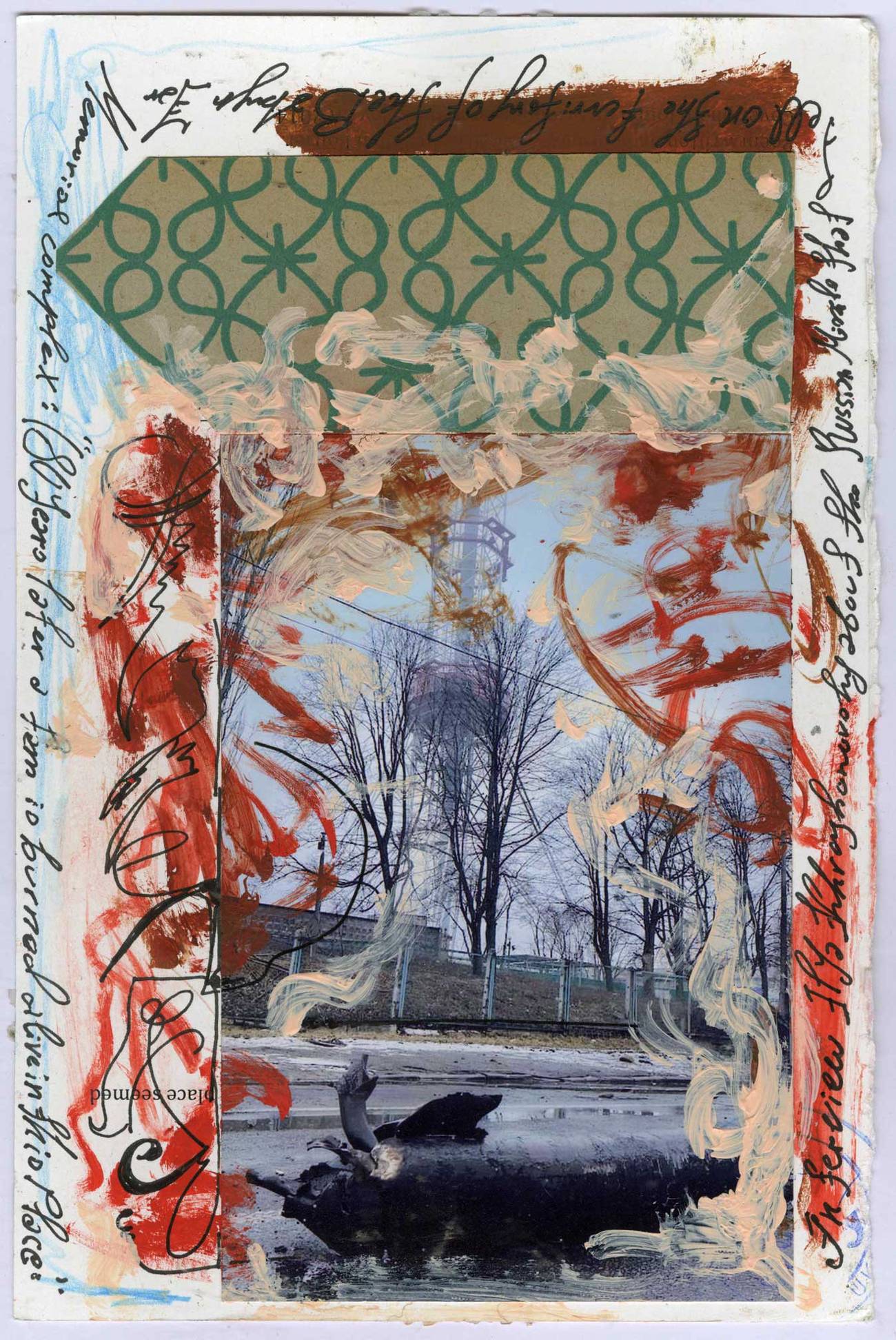

Daybook page November 28, 2022

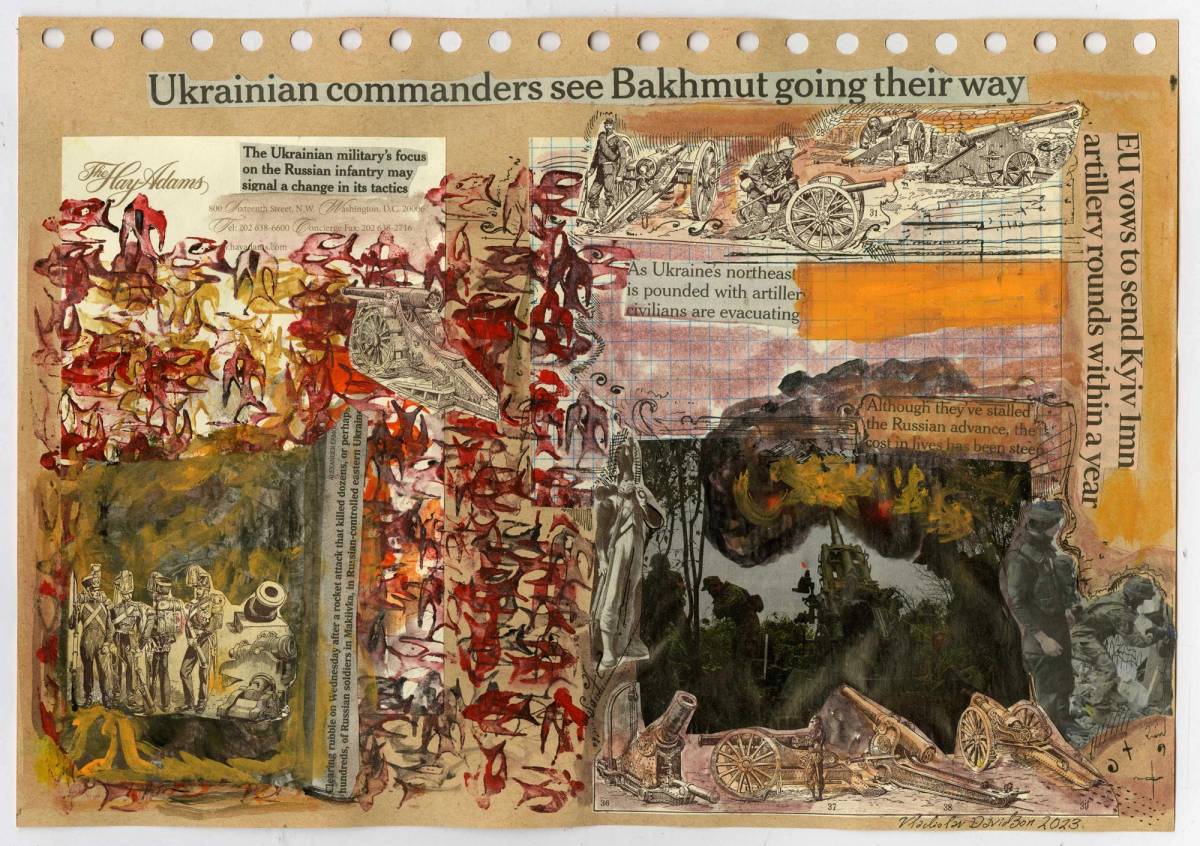

The Guns of Bakhmut

Bakhmut—everyone suddenly seems to know the topography of Ukrainian villages and towns. Months of social media arguments between war junkies, amateur and professional, about the meat grinder and the “kill zone” and which side has the higher kill ratio. Everyone has an opinion on whether the Ukrainians are right to try to hold on to the town, but they have ceased trading territory for time. Plus, why allow a symbolic loss when you will just have to make a stand in the next town over? Trips to fight in Bakhmut are now referred to as a “one-way ticket.” Esteemed retired generals and distinguished historians now routinely use the phrase “Zerg rush”—Zerglings being the expendable foot soldiers of the Zerg, the arthropodal insect species in the StarCraft video game, and the “Zerg rush” being their strategy of throwing an expendable swarm of lightly armored units in a suicidal attack on a defensive position—a tactic that bears a remarkable resemblance to how the Russians use their mobilized prisoners.

Odessa Collage

Spring 2023

Now well into its second year, the Russian war of annihilation against Ukraine has yet to achieve any of the Kremlin’s stated military or political objectives. However, the war has succeeded in cleaving Ukraine off from the rest of the world via air and sea access, thus rendering it almost impossible to get to any major Ukrainian city with less than two days on the road. The intrepid traveler will be forced to spend either a night in a hotel while traversing a neighboring Eastern European country, or in the rather more picaresque environs of a sleeping compartment of a train clattering slowly through the Ukrainian countryside. I am forced to pass through Moldova through a stopover in the Romanian capital, and thus wind up having my passport stamped seven times in between the cities of destination and departure.

Odessa is no longer under radical threat, but the Russians continue to send the occasional swarm of rockets and suicide drones to terrorize the population and force the Ukrainian air defenses to use up valuable anti-air missiles against inexpensive and mass-produced rockets and drones. Soviet and Russian imperial culture is to be effaced if the city is to forge a new identity. The statue of Catherine the Great, who founded the city in 1794, has been taken down after much controversy. Yet there is not much, conceptually speaking, that everyone can agree should be put in her place. The statue of Pushkin on the street named after him has been encased in a box. The statue of Duc de Richelieu on the seaside boulevard has been encased in sandbags. Yet the statues of the nice local Jewish boys who made it big—writer Isaac Babel and Soviet jazz crooner Leonid Utesov—remain free of politics and unencumbered by protective fortifications.

Vladislav Davidzon is Tablet’s European culture correspondent and a Ukrainian-American writer, translator, and critic. He is the Chief Editor of The Odessa Review and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Atlantic Council. He was born in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, and lives in Paris.