Unpacked

In The Cardboard Valise, cartoonist Ben Katchor tries to decode the human impulse toward travel—and rouse the readers of graphic novels from their ‘somnambulistic trance’

If Ben Katchor were a tour guide, he’d be broke. Not because he wouldn’t know his stuff, but because he’d lead his groups into strangers’ apartments and then slip out the bathroom window. He’d run over a fire hydrant as a preamble to a story about the architect of the city’s first waterworks. Then he’d blow up the waterworks.

Katchor isn’t a tour-guide, he’s a cartoonist (the only one to be named a MacArthur “genius”), but fortunately it means he’s available for bookings on a weekly basis if you read the rags smart enough to carry his strips. Or you can go on the grand tour and buy the collections, the most recent of which is The Cardboard Valise.

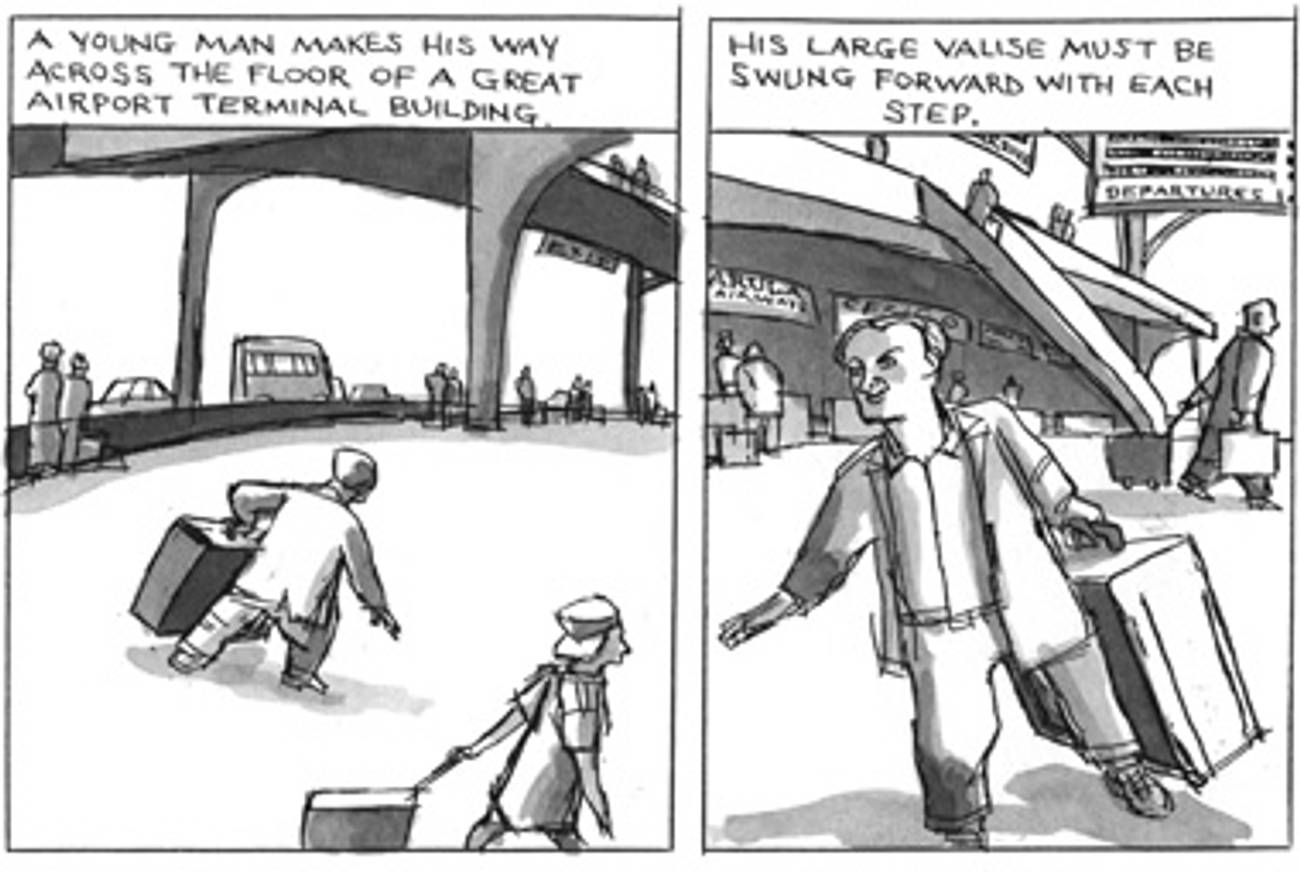

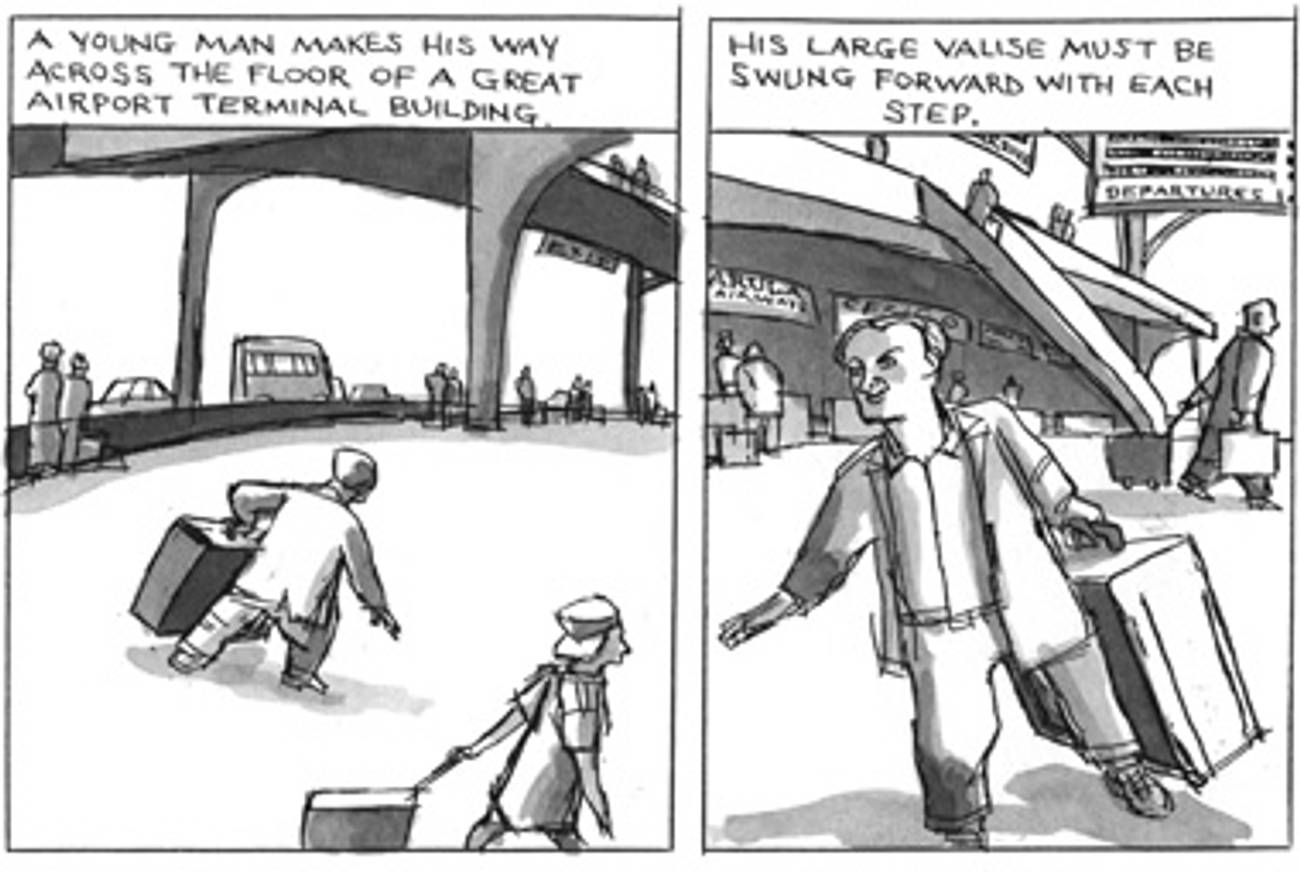

Anyone familiar with his work will recognize his grotesque eccentrics (or maybe his eccentric grotesques), the off-kilter angles and depths of field in every panel, not to mention the banal objects granted strange value and the wonderful prose. It is so unmistakably Katchor that there is an initial fear that it might be a bit stale.

Yet Katchor has left behind the inventive urban landscapes of his previous collections, Julius Knipl, Real Estate Photographer (1996) and The Jew of New York (2000), and abandoned all but the most cursory nod toward a linear narrative for a surreal travelogue from the entirely invented islands of Outer Canthus. There is an exhilaration and freedom here—a license to invent and destroy.

The plot, such as it is, really isn’t the point. Characters might stick around, but more likely they’ll give a speech and never show up again. Impermanence is really the only constant—languages change, dictionaries deteriorate from overuse, an island suddenly evaporates.

Nothing illustrates this sense of impermanence better than the book itself. The outside is brilliantly colored and bears suitcase-like handles—it would fit comfortably on any coffee table—but open it and flanking the collected strips is another narrative telling the story of books going from trees to press to pulp. It is a book aware of its own mortality.

This might be a bit disturbing to the bibliophile, but of course the comic strip is a transient medium meant for the recycling bin, and what magic does a binding grant against entropy?

On the eve of his book’s release, Katchor spoke to Tablet Magazine about the book’s genesis, the problem with most graphic novels, and his trouble with the word “Jew.”

Where did The Cardboard Valise come from?

It was produced as a weekly strip for newspapers and ran for about two years. The book is a collection of those strips in the order they originally appeared, to preserve the sense of free-associative invention that went on each week. The original pages were annotated and expanded upon with some new material.

Julius Knipl and The Jew of New York were both grounded in real places. The Cardboard Valise, to put it mildly, is not. Why the departure—if you feel it is one?

After eight years of working on the Julius Knipl series, I wanted to take a vacation from writing about an imagined, 20th-century North American city, and so I began a new weekly strip based upon surrendering to the touristic impulse. I wanted to undercut that sense of being grounded, or trapped, in a place and culture and feel the momentary sense of freedom and disorientation a tourist experiences went he arrives in a new city or country.

All of these cultural constructs are invented; feeling grounded is just another way of saying we grow lazy and lack the energy needed to keep reinventing the way we do things. Of course, it’s much easier to invent cultures with ink on paper than through full-scale construction in the street.

So, changing places is just an excuse?

After the first few hundred Knipl strips, my stories had very little to do with him—the stories just appeared under his name for no good reason. Also, I felt that readers were becoming too attached to the character of Julius Knipl—he became a cozy surrogate uncle—and I wanted to end that unhealthy situation.

Why is it unhealthy for the readers to become attached?

I don’t want my readers to be lulled into a trance of passive entertainment. I’d like them to consider how the invention of each weekly story relates to their own life and then, hopefully, think of ways of rewriting the narrative of their own situation. They should be reminded constantly of the fact that my strips and their lives are invented situations that can be edited or rewritten—not accepted as in a somnambulistic trance.

Is that why you do away with the book’s initial setting, Tensint Island?

I abruptly destroyed Tensint Island to jar the readers awake from such a narrative trance. That’s why the collection avoids the development of a comforting narrative thread and why characters and situations are discarded as quickly as they are established. Some readers will miss the opiate effect found in many “graphic novels.”

The titular valise seems to be a bit of a metaphor for the flow of your work—“It’s terrible weight, [pulling] him along in a direction slightly different from the one he had intended to follow”—but it also is presented as a bag meant for refugees, but appropriated by tourists. Is there a bit of a self-critique in that?

I’m swayed by my own taste in images and language and other mental baggage. It’s something very evident in serial writing, but visible across any body of work. My collaborations in music-theater have really produced narrative solutions that are not mine, nor my collaborator’s, but a sensibility that’s a surprise to both of us. That may be why much creative work today is done in teams. The private suitcase may have had its day.

You’ve said before that you wrote The Jew of New York because the Forward wanted a more explicitly Jewish strip. There aren’t any Jews in Valise, but is there implicit Jewishness?

The editors of the Forward did not want to run the Knipl series because they felt that it was not specifically Jewish enough—at least that’s what they told me—and so I told them that I’d produce a new strip called The Jew of New York.

I chose that title to convince the editors that it was a specifically “Jewish” strip, and they fell for it. The story has as much to do with the development of the market economy in the 1830s and American theater as it does with the funeral customs of Ashkenazi Jews. How do you know that there are no Jewish characters in The Cardboard Valise?

Good point. I suppose I was thrown off by the lack of dairymen singing about tradition. So, are there Jews? Does it matter?

At this point in history, the word “Jew” by itself doesn’t tell me anything. Using the word by itself is just a lazy way of categorizing the multifaceted history of the world. Anti-Semites deal in such gross generalizations.

In the make-up of some of my characters there is an echo of Jewish history or culture, but in a quantity and of a quality that you might not recognize because of its mixture with a thousand other historical details. If the make-up of human character can be unraveled it’s only on that kind of a microscopic level. The labels of ethnicity and national identity are fraudulent simplifications perpetuated for criminal and/or business purposes.

For instance, purposes like those of The Purple Gang, or a daily online magazine of Jewish ideas, life and culture?

Hopefully, you’re not trafficking in bootleg whiskey or gross generalizations.

What are you working on now?

A history of dairy restaurants [for Nextbook Press] and a show for music-theater about the New York Public Library on 42nd Street.

How are you researching the dairy restaurant history? Eating out a lot?

By studying world history, I’m beginning to understand how and why this form of public eating came about. As food may be the most ephemeral of cultural artifacts, to reconstruct the taste of a blintz in the Famous Dairy on 72nd Street, c. 1970, one must go beyond eating.