Medal of Honor

A great comic book tribute to Tibor Rubin, the only Holocaust survivor to earn America’s highest military honor

The greatest comic book you’ll read this year doesn’t feature a band of intergalactic avengers staving off alien invaders. It has nothing to do with raging green beasts or playboy billionaire inventors or Norse gods locked in sibling rivalry. Unlike anything by Marvel or DC, this one isn’t bloated and flashy—it’s 11 pages long, and spends more time on facial expressions than on flashy effects. Which is just as well, given that its hero is a real-life person whose story is infinitely more moving, thrilling, and inspiring than any of the masked machos its creators helped bring to life.

He is Tibor Rubin, and when we first meet him, he is dug into the dirt on a Korean mountainside. He is alone, but the Chinese army is closing in quickly. The fire emanating from Rubin’s machine gun isn’t the silly stuff of comics; it’s a hellish tongue, lapping everything in its way, a perfect visual representation of man’s inhumanity to man.

And that’s just the first panel; by the second, we meet Rubin again, this time as a child, dressed in a prisoner’s uniform and guarded by the SS. “Rubin learned early about the depth of cruelty his fellow man was capable of,” the comic book laconically informs us, and then conjures a fat-faced German who, looking bemused, tells Rubin that none of the death camp’s Jewish prisoners will survive.

Rubin, thankfully, defies the odds, and when he’s liberated by American soldiers he makes his way stateside and, though not yet a citizen, volunteers to become an American soldier himself.

From that point on, the comic book reads like one of those gritty montages that made old-fashioned war films so fun: Outnumbered by the enemy, Rubin’s outfit, the Third Battalion, decides to withdraw to the Pusan Perimeter. But Rubin decides to stay behind, eager to give the impression that the hill is still fiercely defended by scores of men; he jumps from foxhole to foxhole, seizing carbine and machine gun and grenade, unleashing that infernal fire wherever he goes. By the time the action’s over, the comic book gives us Rubin in profile, looking stoic amid the pale gray rock and the ink-blue sky. “The number of casualties he inflicted,” the text curtly informs us, “was staggering.”

All that would’ve been enough to make anyone a hero, and Rubin’s colleagues moved to file the necessary paperwork to recommend him for the Medal of Honor. They never had the chance to submit it: On Nov. 1, 1950, Rubin and his friends were awakened by the sound of bugles, and soon learned that nearly 400,000 Chinese soldiers were upon them.

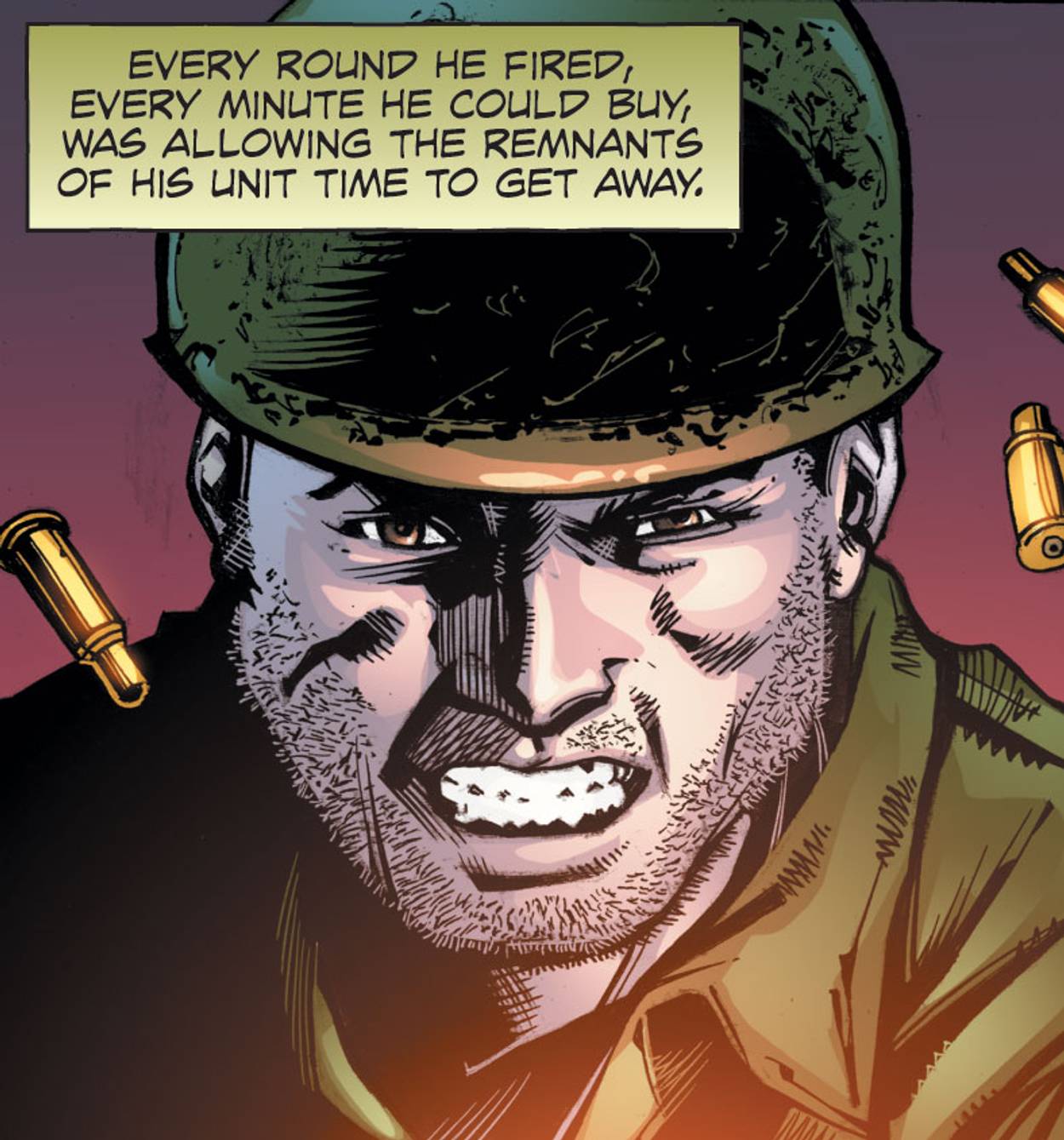

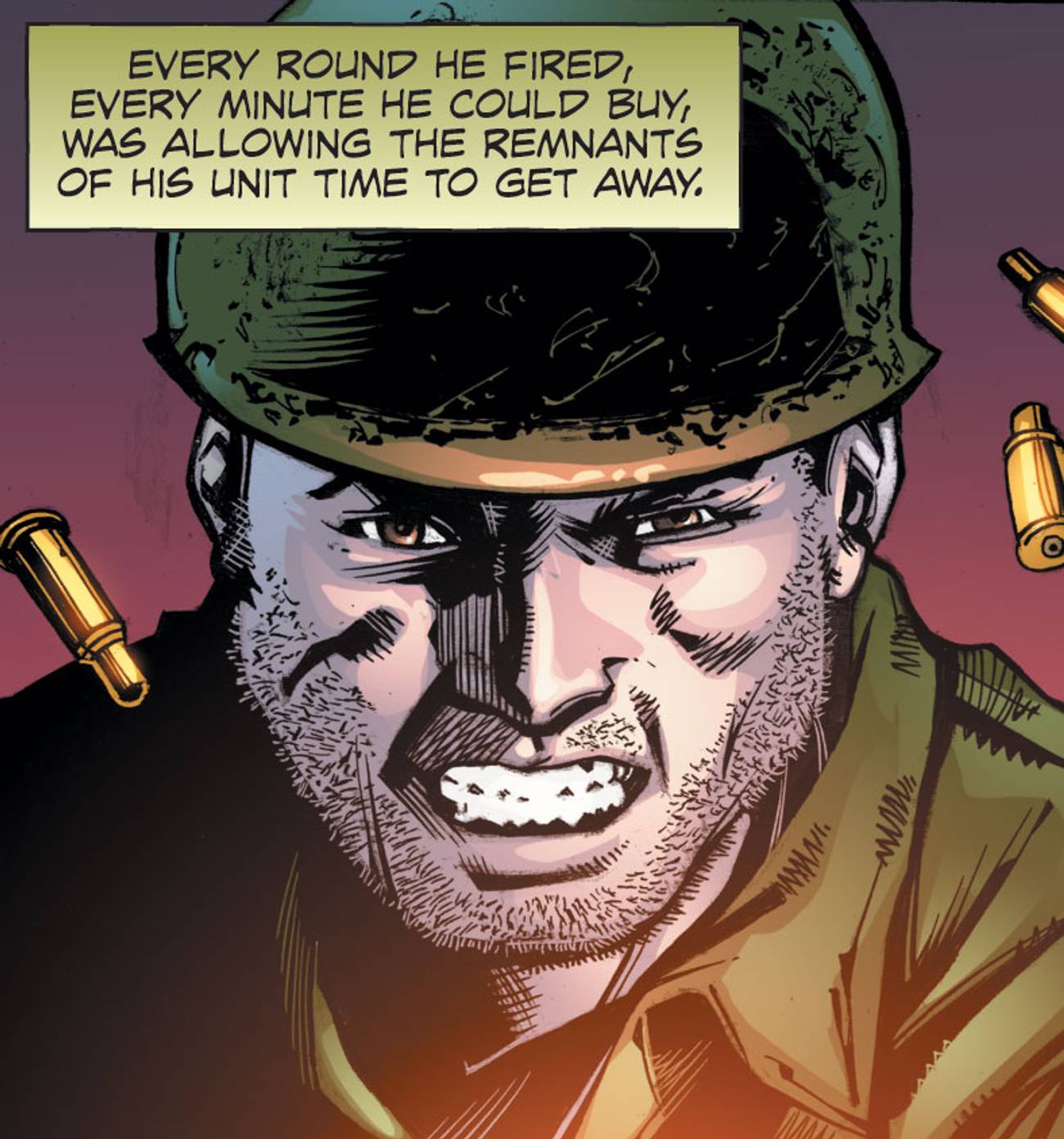

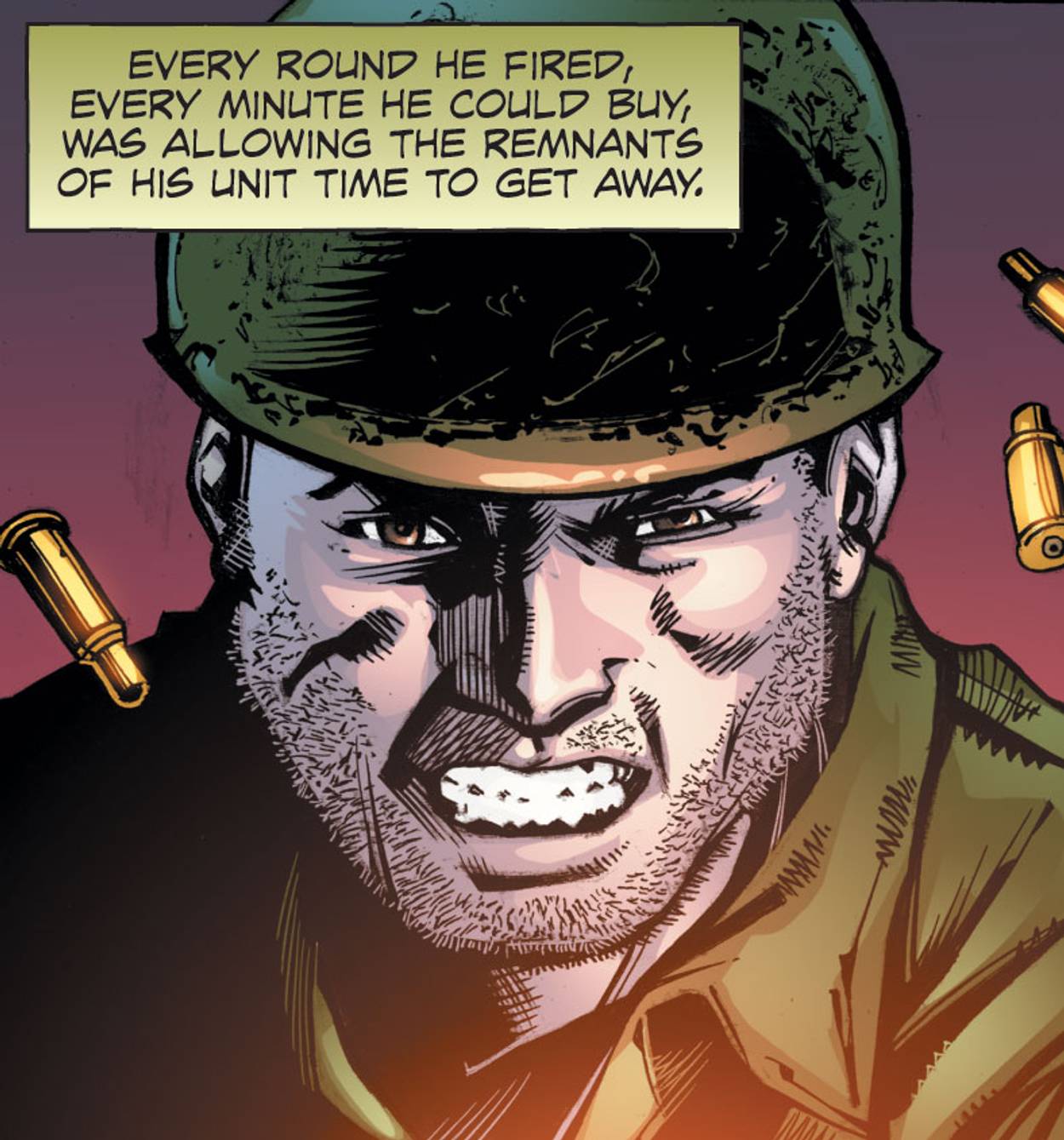

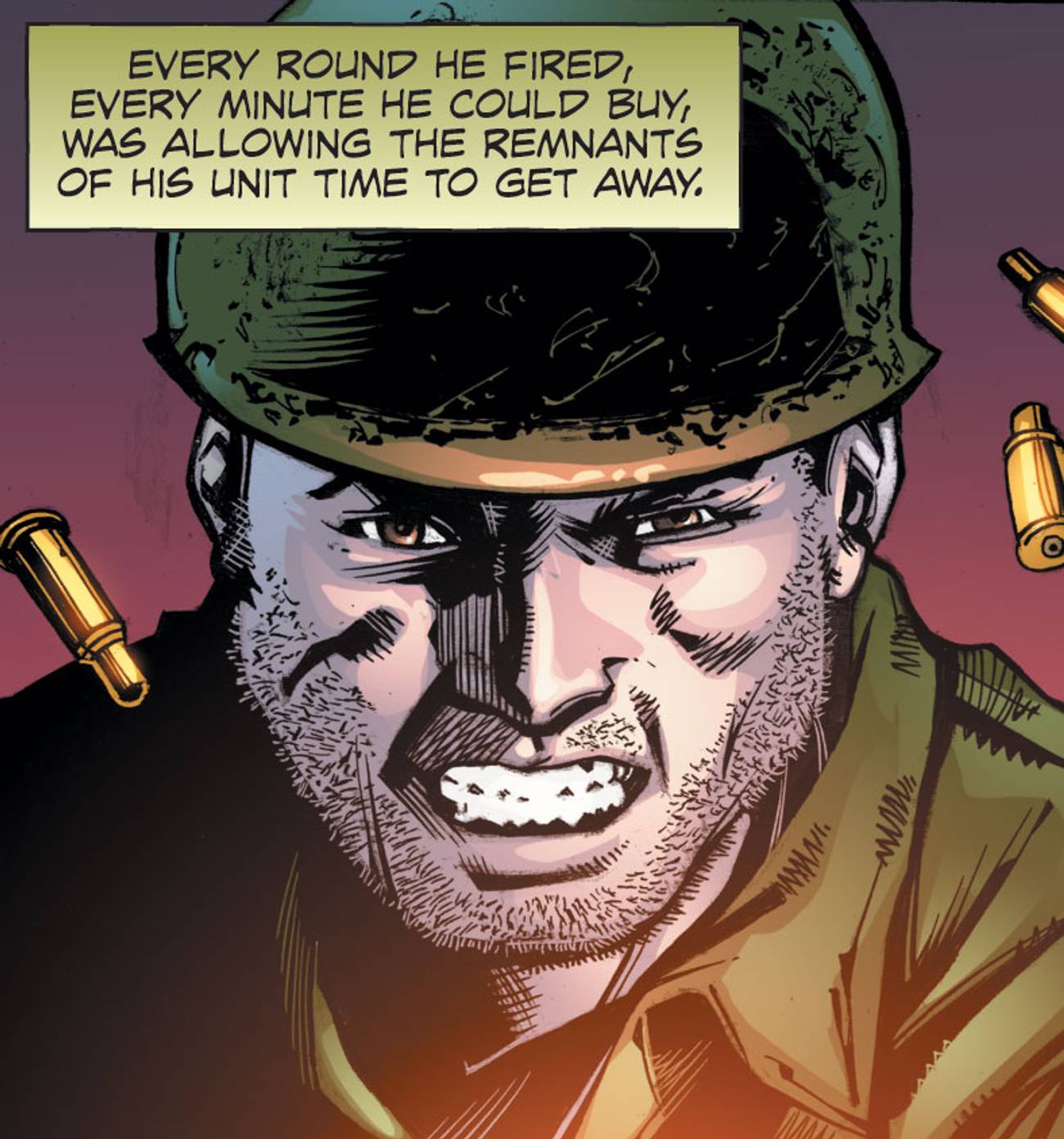

Noticing that the machine gunner on the front line was shot and killed, Rubin crawled under fire and replaced him. He then proceeded to shoot and shoot and shoot, feeding the .30 caliber and giving his friends the cover they needed to retreat to safety. Again and again, they called on him to join them. Again and again, he refused.

Eventually, of course, Rubin ran out of ammo belts, but not before buying his fellow GIs hours rather than minutes to regroup. He was seized by the Chinese and sent to yet another concentration camp, with yet another wicked guard telling him that his chance of survival was nil. When the camp’s commander, noticing that Rubin was a Hungarian citizen, offers to release him and ship him back to his native communist homeland, Rubin refuses: His only home, he says, is the United States of America.

Nothing about his imprisonment dampens his sense of duty or selflessness. Being a survivor of a Nazi camp, he applies all that he’d learned in his youth to the Chinese camp as well, defying his captors at every turn and risking his life to care for and feed his fellow POWs. He does it for three more years, until he is released in a prisoner exchange, returns to America, and spends tens of thousands of hours throughout his life volunteering at a local veterans hospital.

The comic book’s last panel shows Rubin finally receiving the nation’s highest military honor, in September 2005, from President George W. Bush, the only Holocaust survivor to earn it. “A grateful America,” the commander in chief says, smiling, “bestows this award on a true son of liberty.”

Amen to that. Just in time for Veterans Day, and for a nation in dire need of selfless patriots ready to defend our sacred commitment to freedom, this new comic book gives us Tibor Rubin, a superhero we’ve never needed more.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.