The Beilis Conspiracy

A century after the last blood libel trial, the idea that Jews drink Christian vital fluid is still alive and well

Take a midafternoon trip through the most sketchy and monomaniacal corners of the cybersphere, and you will discover that Jews have been blamed for everything from the Holocaust and Sept. 11 to Newtown and climate change. Faced with such frantic spewing, one looks back with a kind of nostalgia to the granddaddy of anti-Semitic tropes: the blood libel, the age-old charge that Jews kill Christian children to use their blood in religious rituals, in particular the baking of Passover matzoh.

The blood libel has had a long life, from its invention in Norwich, England, in 1144 to the pogroms it spurred centuries later in Poland and Russia. While matzoh is rarely a fixation among anti-Semites these days, the notion that Jews kill outsiders for their own nefarious purposes is alive and well, often with Muslim victims substituted for Christian ones. In 2009 the Swedish social democratic newspaper Aftonbladet ran a story alleging, without evidence, that Israelis were harvesting the organs of Palestinians for use on the black market. In the Arab world, Israel has been charged with murdering Palestinian children; in the most pointed versions of the accusation, such murders are seen as a perverse source of enjoyment for the Jews. At Davos in 2009, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Erdogan denounced Israel’s rulers as “murderers of children” and added that “Israeli barbarity is far beyond any usual cruelty.”

Recent times have even seen serious academics wonder whether the blood libel, so serious a source of pain to Jews, might contain a grain of truth. The very thought is nauseating and repugnant. Yet in 2007 Prof. Ariel Toaff of Bar-Ilan University published Passovers of Blood, whose cover showed a dramatic etching of a bearded man poised with his knife above a fearful boy. The cover depicted the akedah, but the book was not about Abraham’s near-sacrifice of Isaac. Instead, Toaff proposed a shocking new perspective on blood libel: He insisted that some medieval Jews used blood in their rituals and implied that they might even, on a few occasions, have murdered Christians for this purpose. Toaff quickly became a taboo-breaking martyr in the eyes of the Internet’s anti-Semitic cultists, who happily proclaimed that he had proved an eternal, and eternally suppressed, truth: Jews have brainwashed the world into thinking they are innocent sufferers, but they don’t hesitate to stoop to murder.

Toaff’s book was speculative and full of innuendo; he stressed in an interview that his hypotheses concerned “a few extremists … between 1100 and 1500.” All his evidence came from confessions under torture, given by Jews who were telling their Christian tormenters exactly what they were required to say. But for his defenders, Toaff had bravely exposed the forbidden truth: The Jew is guilty. Several Knesset members threatened to prosecute Toaff, his university reprimanded him, and he was censured by a group of Italian rabbis (including his own father, the former chief rabbi of Rome): For Toaff’s followers, all this proved the too-hot-to-handle veracity of his claims. Toaff had become a victim of the pitiless Jewish lobby whose tentacles were everywhere and that desperately wanted to silence him.

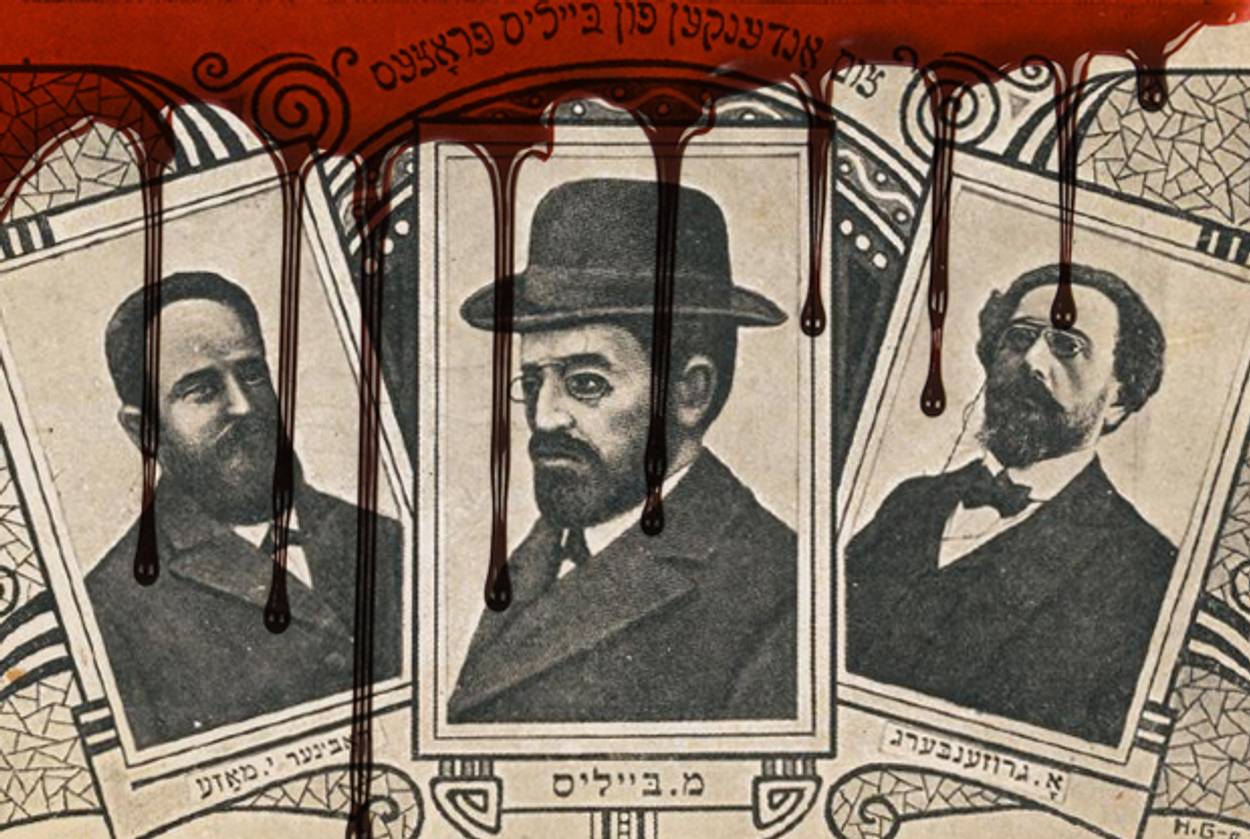

The final blood-libel trial of a Jew in Western history came to court exactly 100 years ago, and in view of the continued popularity of the blood libel it’s worth looking back to this event: the last occasion on which a Jew came to court on the charge of having murdered a Christian child for ritual purposes. When it was over, the accused, Mendel Beilis, thought that he had ended the long tradition of accusing Jews of spilling Christian blood for religious purposes, but he was wrong: The uproar over Toaff’s book showed that the charge of ritual murder remains a testing ground for allegations about the guilt or innocence of the Jewish people as a whole. The blood libel refuses to die, because it’s too convenient a way to evoke the Jewish conspiracy that drains the life from the rest of the world.

***

The trial took place in Kiev in the fall of 1913, and the defendant was a Jew named Mendel Beilis. In July 1911, Beilis, the supervisor of a brick factory in Kiev, found the Russian secret police at his door with their swords drawn, thundering, “In the name of the Czar, you are arrested.” Carted off to jail in front of his wife and five children, Beilis was peppered with a series of relentless questions: Where do you come from? What is your religion?—and, finally, What do you know of the boy Yustchinsky’s murder? Months earlier, a Christian child, Andrei Yustchinsky, had been found murdered in a nearby cave; he had been stabbed repeatedly and the blood drained from his body. The case bore all the marks of a ritual murder.

But the truth about little Andrei’s murder was already apparent long before Beilis went to trial. A female gangster named Vera Tcheberiak, along with her lover—whom she had blinded when, during a jealous quarrel, she threw acid in his face—were in cahoots with Andrei’s mother. Andrei had been in the Tcheberiak lair when it was stuffed full of stolen goods, and during a fight with a playmate he had threatened to tell the police about the gang’s activities. The word leaked out that Andrei was a potential squealer, and so his death sentence was assured. The Tcheberiak crew had an inspiration: If Andrei’s death were made to look like a ritual murder, they might be able to instigate a pogrom, and take advantage of the ensuing chaos to loot Jewish homes freely. Sure enough, at Andrei’s funeral leaflets were distributed that charged the Jews with the murder and urged aggrieved Russians to take up arms against them.

Before he finally entered the courtroom, Mendel Beilis spent over two years in prison, much of it in brutal conditions, in a bug-infested, freezing, filthy cell. As Beilis’ trial approached, a tidal wave of sympathy for him engulfed Russia. News of the case was eagerly followed in Western Europe and America, too. At their Seders, some Jews glossed the Haggadah’s acronym for the plagues on Egypt with a sentence about Beilis, “divrei Tcheberiak kazav, alilat dam sheker, Beilis eino chayav bo”: “the words of Tcheberiak are a deception, the blood libel is a lie, Beilis is not guilty.”

Jews were hardly the only ones to believe wholeheartedly in Mendel Beilis’ innocence. In England, the archbishops of Canterbury and York signed on to Beilis’ cause, along with the speaker of the House of Commons. Vladimir Nabokov’s father, the crusading liberal journalist V.D. Nabokov, covered the Beilis trial for his St. Petersburg paper; the elder Nabokov was heroically opposed to all forms of anti-Semitism in Russian life, a trait he passed on to his son. Another journalist at the Beilis trial in Kiev was an American: George Kennan, uncle of the famous diplomat and author of the authoritative tome Siberia and the Exile System. Kennan’s detailed, chilling report of the trial helped sway public opinion even more in Beilis’ favor.

After the trial was over, Beilis wrote a memoir, The Story of My Sufferings, the most remarkable part of which is his memory of how many non-Jewish Russians, including even a few diehard members of the Black Hundreds (the anti-Semitic organization responsible for many pogroms), ardently professed their support for the beleaguered Jew. When he was in jail, Beilis remembered, a fellow prisoner embraced him and wept, hoping aloud that God would protect Beilis, because “the Jews are an honest people”; when Beilis’ wife and children visited him, prison guards turned aside with tears in their eyes. The detectives first assigned to the case, along with the chief of Kiev’s secret police, were sent to jail as a result of their belief that Beilis must be innocent.

In his trial, Beilis was defiant when he needed to be. He answered one of the judge’s opening questions, “To what religion do you belong?” with, he remembered, “something approaching a shout”: “I am a Jew.” As the trial went on, the prosecution’s case collapsed. The workers that Beilis supervised testified to his honesty; they knew he was incapable of murder. A 10-year-old boy, a friend of the dead Andrei, had been primed by the Tcheberiak gang to testify that Andrei had often played near the brick factory and had been chased off the factory grounds by Beilis. Instead, the boy stated that Andrei had never gone near the factory. The student who had distributed the anti-Semitic leaflets at Andrei’s funeral fainted when he took the stand. Then, in a moment of high drama, the lamplighter who had originally said that Beilis had chased Andrei from the brickyard recanted his testimony, proclaiming, “I am a Christian and fear God. Why should I ruin an innocent man?”

The prize piece of evidence for the prosecution was theological: expert opinion that would prove that Jews engaged in ritual murder. Here, the prosecution thought, was perfect material to sway a jury of uneducated Russian peasants. But they could find only two expert witnesses, and neither of them was persuasive. One was a priest who turned out to be a convert from Judaism; he admitted that he had never seen or heard any trace of ritual murder in his father’s Jewish house, but had only been told of the bloody practice by Christians. The second expert witness was a Catholic priest named Father Pranaitis. (To the prosecution’s dismay, the Orthodox scholars they wanted were nowhere to be found.) Pranaitis claimed to be an accomplished scholar of Jewish practices and beliefs, but the defense unmasked him as a fraud whose knowledge of Hebrew was practically nonexistent. The climax of the hapless priest’s humiliation by Beilis’ legal team (led by Oskar Gruzenberg, who was renowned for his championing of Jewish causes) occurred when they asked Pranaitis, “When did Baba Batra live and what was her activity?” When Pranaitis answered, “I don’t know,” the Jews in the courtroom erupted in laughter. Baba Batra is one of the most famous tractates of the Talmud; but Baba in Russian means grandmother—the Christian “expert” was easily tricked.

The judge, however, stood steadfast in his determination to find Beilis guilty. His final instructions to the jury were somber and pointed: “This trial … has touched upon a matter which concerns the existence of the whole Russian people. There are people who drink our blood.” Despite such heavy-handed instruction, the jury returned a verdict of not guilty (although they did indicate that they believed a ritual murder had occurred).

After the verdict, wild jubilation stormed the courtroom. Beilis reported that a “very distinguished and gigantic looking Russian,” a factory owner who had left his business for a month to attend the trial, approached him with these words: “Now, the Lord be blessed, I can go home rejoicing. … I wish you all the happiness in the world, Beilis.” The freed Jew became an instant celebrity. In the fall of 1913, three plays about Beilis ran at the same time in New York, featuring the greatest stars of the Yiddish stage.

From the moment he became a free man again, Beilis found himself mobbed by throngs of admirers, who had come from all over Europe to see him. At one point, he wrote later, he had 7,000 visitors a day. Some insisted that they must see him or they would commit suicide. A Russian priest knelt and kissed Beilis’ hand, asking forgiveness. Finally, Beilis left Russia, unable to bear the harassment of constant adulation. When his train passed through Lvov, word got out that Beilis was on it: A swelling crowd demanded to see him and threatened to damage the station or sit down on the tracks if he did not appear. Beilis turned away offers to make his home in London and New York and chose Palestine instead. Even in Eretz Yisrael there was a heated competition for his presence: The Jews of Jerusalem reminded him that they had prayed for him at the kotel and told him it would be an insult for him to settle in Tel Aviv—but he did.

Beilis wrote that, during his visit to the Temple Mount, he was permitted to enter the Dome of the Rock by “one of the leading Arabs,” who told him, “You belong to the three great Jewish heroes and martyrs”—Dreyfus was another, the Arab said; Beilis didn’t catch the name of the third. Beilis’ memoir ends with his departure for New York, after nine years in the holy land. The Rothschilds and others had promised Beilis financial assistance. “But could I live on promises?” Beilis lamented that he never received the money. There was no livelihood in Palestine; the new world, the true goldene medina, beckoned.

***

Mendel Beilis entered the limelight again, long after his death in New York in 1934, when Bernard Malamud decided to write a novel based on his prison experience. The novel was The Fixer, which would win for Malamud both the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize in 1967. (The title refers to the hero’s vocation: He is a repairman before he becomes a factory supervisor.) For his book, a tour de force of misery and dry wit, Malamud drew conspicuously on Beilis’ memoir. Six times a day, Beilis wrote, he was subjected to body searches. The door of his cell had 13 heavy locks, and each had to be shot back with a blood-chilling clang before Beilis was stripped and inspected by taunting guards. Malamud changed the number of locks from 13 to 12, but his account of the searches is clearly modeled on Beilis’ version. One of Beilis’ sons later charged Malamud with plagiarizing his father’s memoir; there are in fact strong resemblances between Beilis’ account of his prison life and Malamud’s version.

Before he settled on Beilis, Malamud had thought of writing a novel about Dreyfus; but, he concluded, Dreyfus “was a dullish man … he did not suffer well.” Beilis did suffer well. And no theme was more central to Malamud’s work than suffering. In a letter to his friend Rosemarie Beck, he described his novel’s plot: “A man is put in prison, and there he must suffer out his existence with what he has and, in a sense, conceive himself again. It is, as you see, my old subject matter.”

Malamud too suffered as he wrote The Fixer; the novel required an excruciating, seemingly endless series of drafts. He would remark that “The book nearly killed me—but I couldn’t let go of it.” “I beat myself into shape with a terrible will,” Malamud once said, explaining how he managed to become an author. Nowhere was that will more apparent than in his writing of The Fixer. Malamud at the time was reeling from the aftermath of an affair with a young Bennington student, Arlene Heyman. He began The Fixer in 1963, just when he wrote to Heyman, who had ended the affair, to tell her that he was breaking off all contact with her. He was shutting himself off, in an act of solidarity with his persecuted hero. (Malamud and Heyman later reconciled, and he held one of the huppah poles at her wedding.)

Malamud’s Beilis figure, Yakov Bok, is the ne plus ultra among the author’s sufferers: isolated, poor, frustrated in love, blessed by nothing but a sardonic sense of humor about his troubles. Like most of Malamud’s heroes, he is, as Robert Alter put it, “nailed to the cumbersome load of his wearying work”: His destiny is ill-fitting, like a bad suit. Malamud disagrees with Kafka’s stark, uncanny sense of the eternal lack of fit between the human being and his fate: The humbler Malamud sees, instead, an ordinary and bruising mismatch between the individual and the role he is forced to play. Malamud once referred in an interview to “the cultural deprivation I felt as a child”: There were no books or music in his parents’ home and no pictures on the walls; it was, he felt, a kind of prison. Malamud wrote about Jews because he saw the Jew as the “prisoner of history”; but really, as he once blurted out, “all men are Jews”—and all men are prisoners.

There are a number of differences between Mendel Beilis and Malamud’s fixer. Yakov Bok is childless and has even been abandoned by his wife (for a Gentile, no less); he is an inveterate reader of Spinoza and a religious doubter, whereas Beilis was conventionally religious (though he had to work on the Sabbath, since his factory was open Saturdays). Yakov Bok fearfully masquerades as a non-Jew in order to make his way in Kiev, the “holy city” traditionally closed to Jews; by contrast, Beilis easily received a special dispensation from Zaitsev, the wealthy Jewish owner of the brick factory, allowing him to live on the factory premises. Most important, Malamud’s hero is alienated from the goyish world that surrounds him in Kiev, as well as from the tradition-bound ways of the Jewish shtetl that he fled. Beilis had no such discomfort with either the Jewish religion or with Gentiles: He sent his sons to heder and was popular with his Christian neighbors.

Malamud moves from the Jew as archetypal sufferer to the Jew as omnipotent avenger

The most crucial difference between The Fixer and the Beilis case is Malamud’s decision to depict Beilis as an oppressed prisoner rather than a man successfully defending himself in court. In the Beilis trial, Jews, and sympathetic Gentiles along with them, were given a chance to stand up for their rights. But the rise of Nazi Germany a mere two decades later erased this possibility; a fair trial seemed a relic of a bygone, more enlightened age. Malamud, as he drew on the Beilis case, omitted the trial completely. He wrote in the wake of an era in which Jews were denied all opportunity to speak for themselves, in which they were condemned en masse as guilty.

The result of the Nazi nightmare was that Malamud had to go outside of history to suggest the triumph of the accused Jew, since the Germans had obliterated the hope for such a victory. Unreality infiltrates the narrow world of The Fixer, most noticeably in the fantasy that finally sets Yakov Bok free: At the book’s end, he interrogates and kills Czar Nicholas II and is acclaimed by a roaring crowd.

Like Hollywood with its recent spate of movies about Jews who defend themselves violently when faced with Nazi persecutors, Malamud in the final pages of The Fixer moves from the Jew as archetypal sufferer to the Jew as omnipotent avenger. Both these roles are disquieting, unsatisfying; they testify to the persistent grip of myth on our ideas about Jewish identity. But there is still no way to skirt the myths entirely, to insist that proclamations of Jewish guilt and Jewish innocence, Jewish victimhood and Jewish mastery, merely get in the way of our diverse peoplehood. Jewish identity is made out of myth, too, even as Jews remain properly wary about the risks of subscribing to fantasy images of themselves. There is real danger here: The blood libel, like nothing else, shows the strength of the outside world’s addiction to fantasies about Jews.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

David Mikics is the author, most recently, of Bellow’s People: How Saul Bellow Made Life Into Art. He lives in Brooklyn and Houston, where he is John and Rebecca Moores Professor of English at the University of Houston.

David Mikics is the author, most recently, of Stanley Kubrick (Yale Jewish Lives). He lives in Brooklyn and Houston, where he is John and Rebecca Moores Professor of English at the University of Houston.