The Takeover

Self-righteous professors have spawned self-righteous students and unleashed them into the public square

In 1987 I published The Last Intellectuals: American Culture in the Age of Academe which elicited heated responses. Only now do I see I got something wrong—as did my critics. Some had objected to a term I introduced, “public intellectual,” as redundant and misleading. Others rejected the main argument. I proposed a generational account of American intellectuals. For earlier American intellectuals, the university remained peripheral because it was small, underfunded, and distant from cultural life. The Edmund Wilsons and Lewis Mumfords earlier in the 20th century to the Jane Jacobs and Betty Friedans later saw themselves as writers and journalists, not professors. But I missed something, the dawning takeover of the public sphere by campus denizens and lingo.

What I called a transitional generation, the largely Jewish New York intellectuals, ended up later in their careers as professors, but usually they lacked graduate training. When Daniel Bell was appointed to the faculty of Columbia University in 1960, officials discovered that he did not have a Ph.D.—and bestowed it on him for his collection of essays (The End of Ideology). This incident indicates something of the commitment of these men—and they were men; they wrote essays for a public, not monographs or research papers for colleagues. This orientation was as true for a confrere of Bell, like Irving Howe, who also ended up as a professor without graduate training. He observed that like himself Bell did not want to write long-winded treatises; nor did they want to specialize or get pigeonholed. Or as Bell phrased it for all of them, “I specialize in generalizations.”

But the story changes for the next generation—my ’60s generation. In pose we were much more radical than previous American intellectuals. We were the leftists, Maoists, Marxists, Third Worldists, anarchists, and protesters who regularly shut down the university in the name of the war in Vietnam or free speech or racial equality. Yet for all our university bashing, unlike earlier intellectuals, we never exited the campus. We settled in. We became graduate students, assistant professors and finally—a few of us—leading figures in academic disciplines.

To be sure, this was not simply a series of individual choices. The conditions that funneled the transitional generation onto campuses were hard to resist. The life of the freelance intellectual, always precarious, had become virtually impossible. Living in cities turned increasingly expensive as writing outlets diminished. When Edmund Wilson wrote for The New Republic in the 1920s the proceeds of one article could foot the bill for room and board for several months. Sixty years later the payment could fund a few meals. At the same moment, in the 1950s and ’60s, students poured into campuses and faculties enlarged. For young intellectuals, the signs all pointed in one direction: an academic career. Earlier American intellectuals imagined moving to New York or Chicago or San Francisco to join an urban bohemia; my generation imagined moving to college towns like Ann Arbor or Berkeley or Austin to join the conference-going set.

Within 30 years, the timber and tone of faculties were refashioned. In the 1950s the number of public leftists teaching in American universities could be counted on two hands. By the 1980s, they filled airplanes and hotel conference rooms. In the 1980s a three-volume survey of the new Marxist scholarship appeared (The Left Academy: Marxist Scholarship on American Campuses, vol. 1-3). Endless new journals, each with their own followings, popped up, such as Studies on the Left, Radical Teacher, Radical America, Insurgent Sociologist, Radical Economists. In the coming years leaders of the main scholarly organizations like the Modern Language Association or American Sociological Association elected self-professed leftists.

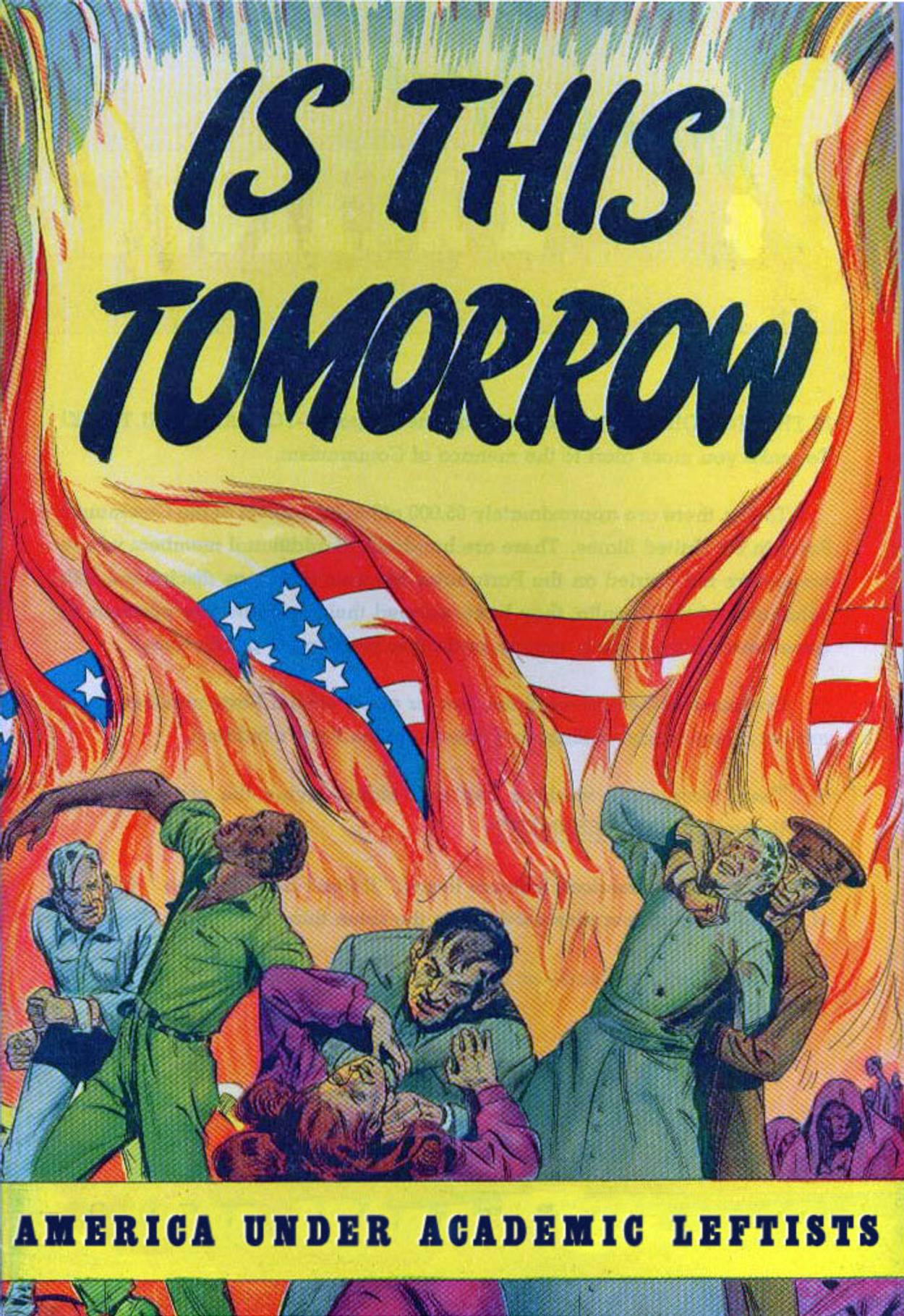

Herein the story gets tangled. In a series of bestselling books—Tenured Radicals, Illiberal Education, The Closing of the American Mind—conservatives raised the alarm: Radicals were taking over the university and destroying America, if not Western civilization. In The Last Intellectuals I differed. The new radical scholars were proving to be obliging colleagues and professionals. The proof? They penned unreadable articles and books for colleagues. They were less subversive than submissive. Earlier American intellectuals wrote for a public; the new radical ones did not. They were not public intellectuals, but narrow academics.

The “famous” Marxist literary professsor was famous only to graduate students in literature. From Homi K. Bhabha at Harvard to Gayatri Spivak at Columbia, Fredric Jameson at Duke and Judith Butler at Berkeley, the leftist politics of these scholars could not be doubted, but what was their impact inasmuch as they could not write? A half serious, bad-writing contest awarded a prize to professor Butler for this sentence:

The move from a structuralist account in which capital is understood to structure social relations in relatively homologous ways to a view of hegemony in which power relations are subject to repetition, convergence, and rearticulation brought the question of temporality into the thinking of structure, and marked a shift from a form of Althusserian theory that takes structural totalities as theoretical objects to one in which the insights into the contingent possibility of structure inaugurate a renewed conception of hegemony as bound up with the contingent sites and strategies of the rearticulation of power.

I argued that the conservatives should awake from their nightmare of radical scholars destroying America and relax; academic revolutionaries preoccupied themselves with their careers and perks. If they made waves, they were confined to the campus pool. In my more paranoid moments, I wondered if a cunning plan had been enacted: Conservatives pretended to be outraged at radicals on campus, but faced with a generation of subversive students, they judged it would be better to keep them locked up in the university, which would limit the damage. The secret appendix to The Conservative Strategy for the Twentieth First Century declared, “Let us give the radicals English and Comparative Literature, gender studies, sociology, history, anthropology and whatever other departments and cockamamie centers they want on campuses, while we take over the rest of America.” The plan largely worked. I wrote at the time, if given the chance it would be worth trading every damn left-wing English department for one Supreme Court. It would still be worth it.

My critics charged that I suffered from nostalgia for some old white dudes. Intellectual life had markedly improved and diversified. Moreover, I overgeneralized; they presented names of a half-dozen stalwart freelancers or well-known professors. This argument continues.

But my critics and I both missed something that might not have been obvious 30 years ago. By the late 1990s the rapid expansion of the universities came to a halt, especially in the humanities. Faculty openings slowed or stopped in many fields. Graduate enrollment cratered. In my own department in 10 years we went from accepting over a hundred students for graduate study to under 20 for a simple reason. We could not place our students. The hordes who took courses in critical pedagogy, insurgent sociology, gender studies, radical anthropology, Marxist cinema theory, and postmodernism could no longer hope for university careers.

What became of them? No single answer is possible. They joined the work force. Some became baristas, tech supporters, Amazon staffers and real estate agents. Others with intellectual ambitions found positions with the remaining newspapers and online periodicals, but most often they landed jobs as writers or researchers with liberal government agencies, foundations, or NGOs. In all these capacities they brought along the sensibilities and jargon they learned on campus.

It is the exodus from the universities that explains what is happening in the larger culture. The leftists who would have vanished as assistant professors in conferences on narratology and gender fluidity or disappeared as law professors with unreadable essays on misogynist hegemony and intersectionality have been pushed out into the larger culture. They staff the ballooning diversity and inclusion commissariats that assault us with vapid statements and inane programs couched in the language they learned in school. We are witnessing the invasion of the public square by the campus, an intrusion of academic terms and sensibilities that has leaped the ivy-covered walls aided by social media. The buzz words of the campus—diversity, inclusion, microaggression, power differential, white privilege, group safety—have become the buzz words in public life. Already confusing on campus, they become noxious off campus. “The slovenliness of our language,” declared Orwell in his classic 1946 essay, “Politics and the English Language,” makes it “easier for us to have foolish thoughts.”

Orwell targeted language that defended “the indefensible” such as the British rule of India, Soviet purges and the bombing of Hiroshima. He offered examples of corrupt language. “The Soviet press is the freest in the world.” The use of euphemisms or lies to defend the indefensible has hardly disappeared: Putin called the invasion of Ukraine “a special military operation,” and anyone calling it a “war” or “invasion” has been arrested.

But today, unlike in 1946, political language of Western progressives does not so much as defend the indefensible as defend the defendable. This renders the issue trickier than when Orwell broached it. Apologies for criminal deeds of the state denounce themselves. Justifications for liberal desiderata, however, almost immunize themselves to objections. If you question diversity mania, you support Western imperialism. Wonder about the significance of microaggression? You are a microaggressor. Have doubts about an eternal, all-inclusive white supremacy? You benefit from white privilege. Skeptical about new pronouns? You abet the suicide of fragile adolescents.

“Diversity” is exhibit A in the campus invasion of the public square.

Everyone loves diversity. Why not? As a human quality it is better than the reverse, homogeneity. Yet diversity exemplifies the murky lingo that defends the defensible. What does diversity entail? More representation of every group? Fair enough, but is this diversity if every individual must incarnate the group, a notion which is almost the antithesis of individual diversity? Moreover, diversity focuses on visible group markers—gender, race, ethnicity—which sidelines diversity of ideas, politics and religion as well as economic class, which are less easy to track. If all agree, but partake of different groups, where is diversity?

Does diversity mean that every sector of society must demographically mirror the composition of the country as a whole? Apparently so, but does this make for a more diverse world? A new study of diversity in Hollywood run by UCLA, and sponsored by blue-chip corporations, uses demographics of gender, race and ethnicity as the self-evident standard to measure diversity. The Hollywood study reports that “People of color accounted for 38.9 percent of the leads in top films for 2021 … At 42.7 percent of the U.S. population in 2021, people of color were again just short of proportionate representation among film leads.” The gap of 3.8 percentage points troubles the diversity mavens. Work to be done, comrades!

But where does diversity defined as proportionate representation lead or stop? Indian Americans are overrepresented among motel owners. What to do? Vietnamese Americans largely staff nail salons. A problem! Too many Jewish lawyers—and too few Jewish NBA basketball players. None, in fact! Has the NBA addressed its diversity crisis? Moreover, diversity-as-proportional-representation historically has worked to discriminate—for instance at a Harvard frightened by too many Jewish applicants. The rising number of Jewish students alarmed Harvard President A. Lawrence Lowell. Jews with 3% of the population inched above 20% of the Harvard student body by the 1920s. Yikes! Lowell in correspondence with his peers at Princeton and Yale, worked to cap the numbers of Jews on campus at 5%. Did antisemitic quotas bolster diversity at Harvard, Princeton, and Yale?

Compared to diversity, the other campus exports are small potatoes, but their importance is growing. Take free speech. The new arguments that question free speech stem from robed academic leftists, an irony that is sometimes noticed. The Free Speech Movement at UC Berkeley virtually inaugurated the ’60s student protest. Historically on and off the campus leftists fought censorship and defended free speech. No longer.

Now law professors, who often call themselves anti-pornography feminists and critical race theorists, advance ideas to curtail free speech. In their tortuous writings, one finds all the terms that they picked up from the postmodern Marxists or the post-Marxists—hegemony, discourse, power, invention. To this they add misogyny, white supremacy, and a dash of paranoia. For all their sophistication, these learned professors are continuously gobsmacked by the most elementary facts of society. Society is hierarchal! The rich have more clout than the poor! The powerful dominate the weak! They repeat these observations endlessly, as if they just discovered them. Apparently, they just did.

The first sentence of an article by Catharine A. MacKinnon, a chaired professor at the University of Michigan and Harvard Law schools, who is the leading anti-pornography feminist, runs: “The First Amendment over the last hundred years has mainly become a weapon of the powerful.” She specifies: “A First Amendment appeal is often used to support dominant status and power, backing white supremacy and masculinist misogynistic attacks.” It is a means for “dominant groups to impose and exploit their hegemony.” Note all the buzz words: dominant power, white supremacy, hegemony. The position marks a sharp shift from the traditional civil libertarians, who prized free speech as protection for dissenters. These civil libertarians are now dismissed as misguided First Amendment absolutists or worse, right-wingers, even Fox viewers.

A problem emerges from the half-baked Marxism of the law professors and their students, who toil and tweet in NGO land. Marx did declare that the ideas of the ruling class are the ruling ideas, but qualified that both cleavages exist in the ruling class and that a new revolutionary class challenges the dominant ideas. Perhaps he was wrong, but at least he posited movement and conflict. It could also be noted that the term “hegemony,” a favorite of campus leftists, derives from the work of the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci. For all his subtlety and inconsistencies, the imprisoned Gramsci saw social antagonisms as ever-present. As one commentator has put it, “Gramsci’s concept of hegemony” provides the basis for an intellectual elite to engage in a “war of position” that will prepare the way “to overthrow the existing order.”

War of position? Nothing could be further from the minds of these professors, who portray power as omnipresent and static. That the First Amendment is a tool of the powerful, professor MacKinnon’s pathbreaking insight, comes right out of hackneyed Marxism; it could be said with equal truth about any sector of society. “Housing is a weapon of the powerful.” “The media is a weapon of the powerful.” “Education is a weapon of the powerful.” For that matter professor MacKinnon, who teaches to the most privileged at the most elite schools, is a weapon of the powerful.

In the classic American case of 1919 Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. set out the criterion of “a clear and present danger” to the state as reason to curb free speech. Holmes wrote the opinion in which two socialists, who had distributed leaflets that encouraged peaceful resistance to the draft, were arrested. The leaflets proposed among other things that draftees “Assert Your Rights.” In 1919 such talk constituted “a clear and present danger” to the government. They were convicted and jailed.

Holmes in subsequent cases, retreated from that standard as too lax or dangerous; that is, it gives the government too much latitude to censor. In general, civil libertarians have always argued that restrictions on free speech should be few and far between, confined to direct threats to institutions or people. We find this already in John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty. “An opinion that corn dealers are starvers of the poor, or that private property is robbery, ought to be unmolested when simply circulated through the press, but may justly incur punishment when delivered orally to an excited mob assembled before the house of a corn dealer.”

The new free speech restricters balloon the category of injury and replace individual harm with group harm. “We have not listened to the real victims,” declares Charles R. Lawrence III, one of the principals in critical race theory. We have shown “little empathy or understanding for their injury.” For Lawrence “insulting words” are “experienced by all members of a racial group who are forced to hear or see these words.”

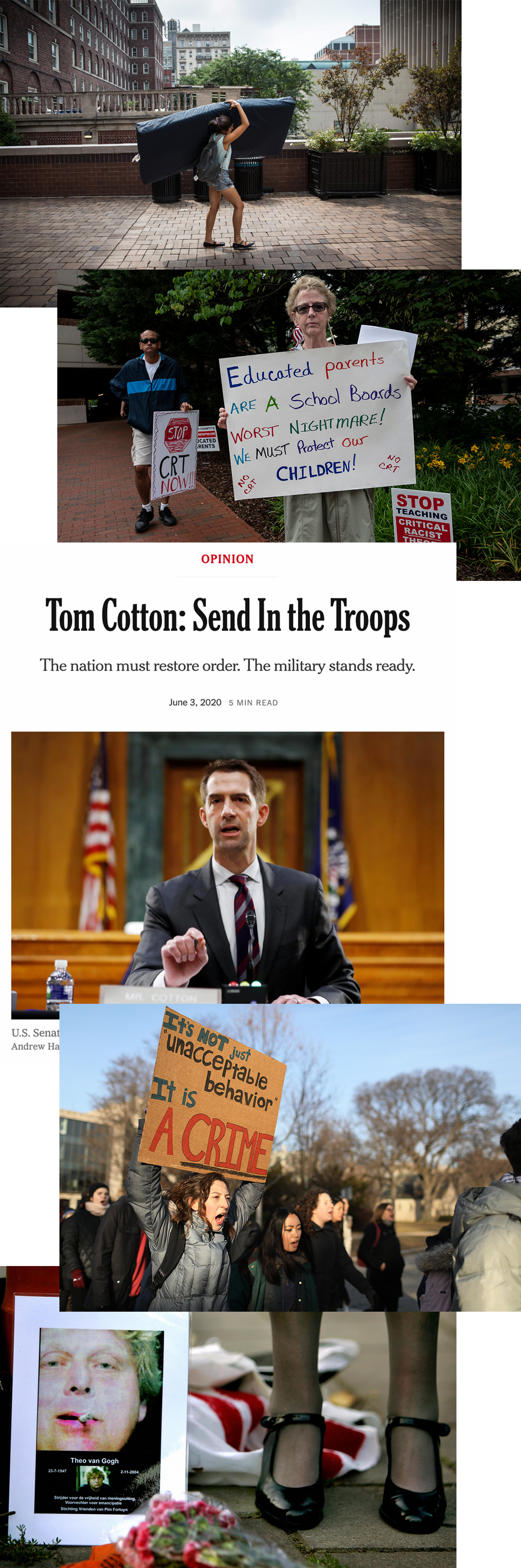

Laura Kipnis, a film professor at Northwestern University, has written about her ordeal when she upset campus tranquility. Her offense? She penned an article in The Chronicle of Higher Education that questioned what she called the sexual paranoia on campuses. Repeat: An article in a trade newspaper upset students, who felt threatened and unsafe by her piece. The students marched through the campus, lugging a mattress. “We, the undersigned, are therefore calling for a swift, official condemnation of the sentiments expressed by Professor Kipnis in her inflammatory article.” One of the principals complained the article “harmed” students. The university readily opened an investigation that dragged on for months.

The New York Times published an opinion piece by Sen. Tom Cotton that called for the national guard to stem looting in the wake of the George Floyd riots. Employees of the Times protested and charged that the piece put Black staffers “in danger.” Again, this was an article in the editorial section of the paper, page 14. In the American adaption of Stalinist show trials, the editor of the opinion section confessed. He regretted “the pain” he caused. He resigned.

A stalwart progressive magazine, The Nation, apologized for a short poem it published. A white poet assumed the voice of a Black homeless woman. The magazine now appends to the poem an apology—longer than the poem—which regrets that the poem contains “disparaging and ableist language that has given offense and caused harm to members of several communities.” The poetry editors are “sorry for the pain we have caused to the many communities affected by this poem.” The poet apologized “for the pain I have caused.” He was sent to a reeducation camp.

In early 2015, two French Muslims forced themselves into the French satirical journal Charlie Hebdo, which published caricatures of Muhammad. They shot 12 people point blank—writers, cartoonists, and others. In the spring of that year the American branch of PEN, the international association of writers, wanted to bestow on the magazine its “freedom of expression award.” It would seem cut and dry: writers and cartoonists killed in cold blood for their satirical work. But no. Some of America’s most celebrated writers protested the award to Charlie Hebdo. They did not exactly support the murders. “An expression of views, however disagreeable, is certainly not to be answered by violence or murder,” they opined. The “certainly” is a nice touch, as if doubt arises. But “power” exists and the “inequities” between those who write and those written about “cannot, and must not, be ignored.”

The writers, who were killed, had power. The killers, not so much. “To the section of the French population that is already marginalized, embattled, and victimized, a population shaped by the legacy of France’s various colonial enterprises, and that contain a large percentage of devout Muslims, Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons of the Prophet must be seen as being intended to cause further humiliation and suffering,” the PEN letter lectured. Several hundred very righteous writers, including Teju Cole, Deborah Eisenberg, Michael Ondaatje, Joyce Carol Oates, and Francine Prose fixed their signatures. To the extent that writers possess power, compared to nonwriters (or noncartoonists)—as indicated in the PEN protest letter—the inequalities might block all writing, except about oneself, a temptation many writers already find irresistible.

With marginality as the limit for free speech, how might have the new arbiters viewed Voltaire and his brethren of 18th-century France. The philosophes were an elite who attacked the benighted Catholics, who probably felt injured and disrespected. The power of the church was fast crumbling—it would soon be disestablished in the French Revolution—and the good Catholics were often rural and poor. Weren’t they marginalized?

In 2004 Theodoor van Gogh, a Dutch actor and film producer, was murdered in the streets of Amsterdam—on his bicycle—by a Muslim extremist. He had made a 10-minute provocative film with Ayaan Hirsi Ali, the feminist born to a Muslim Somali family, that denounced the treatment of women in Islamic societies. The assassin pinned a note with a knife to van Gogh’s body that threatened Hirsi Ali. In his book Murder in Amsterdam, Ian Buruma considers the events and its principals, but like today’s free speech skeptics observes that Hirsi Ali attacked a marginalized community, “a minority within an embattled minority.” In that sense, he comments, Hirsi Ali is no Voltaire.

Yet the same issue emerges. What makes a marginalized community, which constrains free speech? The 1989 fatwa against Salman Rushdie ordered Muslims anywhere to execute the author, with a fat reward bankrolled by Iran for this pious deed, and it encompassed not only Rushdie but his publishers and translators. There are well over 1 billion Muslims. Rushdie himself noted that over the decades support for him has ebbed. People who once defended me, he observed, would now “accuse me of insulting an ethnic and cultural minority.”

The situation of the estimable Voltaire could not be more different than the current critics of Islam; he lived at the border of France and Switzerland, so he could quickly flee if French authorities sought to arrest him. Along with other philosophes he never dreamed he could be killed either by the state or angry Catholics anywhere. Detained, censored or exiled, yes. Murdered, no. Voltaire had no security detail—unlike Rushdie and Hirsi Ali. For critics of religious dogmatism in 18th-century France, the possibility of getting killed was zero. For critics of Islam in the 21st-century world, the possibility of injury or death is real—as the critics know. The comment by Buruma, which is seconded by others, could be more justly reversed: Voltaire was no Hirsi Ali.

When employees protest that they feel unsafe because their company is publishing an offensive article or book, we know what university courses they have taken. When the ACLU drops any mention of the First Amendment from its annual reports; when one of its directors declares, “First Amendment protections are disproportionately enjoyed by people of power and privilege”; and when its counsels its own lawyers to balance free speech and “offense to marginalized groups,” we know they studied critical race theory. When women are dropped from Planned Parenthood literature with the explanation, “It’s time to retire the terms ‘women’s health care’ and ‘a woman’s right to choose’ … these phrases erase the trans and non-binary people who have abortions.” Or when the NARL (National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws) announces it is replacing the phrase pregnant women with “birthing people” and declares, “We use gender neutral language when talking about pregnancy, because it is not just cis-gender women who get pregnant”; we know those who authored these changes majored in gender studies and critical blather.

We know this, but we have to suffer the consequences. The self-righteous professors have spawned self-righteous students who filter into the public square. The former prospered in their campus enclaves by plumping each other’s brilliance, but they left the rest of us alone. The latter, their students, however, constitute an unmitigated disaster, intellectually and politically, as they enter the workforce. They might be the American version of the old Soviet apparatchiks, functionaries who carry out party policies. Intellectually, they fetishize buzz words (diversity, marginality, power differential, white privilege, group safety, hegemony, gender fluidity and the rest) that they plaster over everything.

Politically, they mark a self-immolation of progressives; they flaunt their exquisite sensibilities and openness, and display exquisite narcissism and insularity. Once upon a time leftists sought to enlarge their constituency by reaching out to the uninitiated. This characterized a left during its most salient phase of popular front politics. No longer. With a credo of group safety the newest generation of leftists does not reach out but reaches in. It operates more like a club for members only than a politics for everyone.

Russell Jacoby is the author of 10 books, most recently On Diversity: The Eclipse of the Individual in a Global Era and Intellectuals in Politics and Academia. He is Professor Emeritus, Department of History, UCLA.