The Summer of Love and the Wrath of Cheetah

Hippie memories of California Gov. Ronald Reagan’s bad jokes

Exactly 50 years ago in San Francisco and a few other places, the hippie renaissance entered into its moment of full, fragrant, and intoxicating bloom, which is a moment you can laugh at—should laugh, as a sign of your own intelligence—but shouldn’t laugh too much—or rather, should laugh in the right way, aware that laughter is wisdom, is ecstasy—but not in the wrong way, the laughter of say, Bob Hope, plastic product of corporate odiousness, the cackle of Hollywood, of television, and of death—but where was I? I had begun my first sentence. I meant to say that, exactly 50 years ago, the Summer of Love was ablossom, and, although you can laugh—here is where I lost track—you ought not to suppose that every absurdity was altogether risible, even if risibility may have been inherent in the scene, and, in its upward slippage or aufhebung into the higher, Die Knospe verschwindet im Hervorbrechen der Blüte—but, oh dear, let me try again.

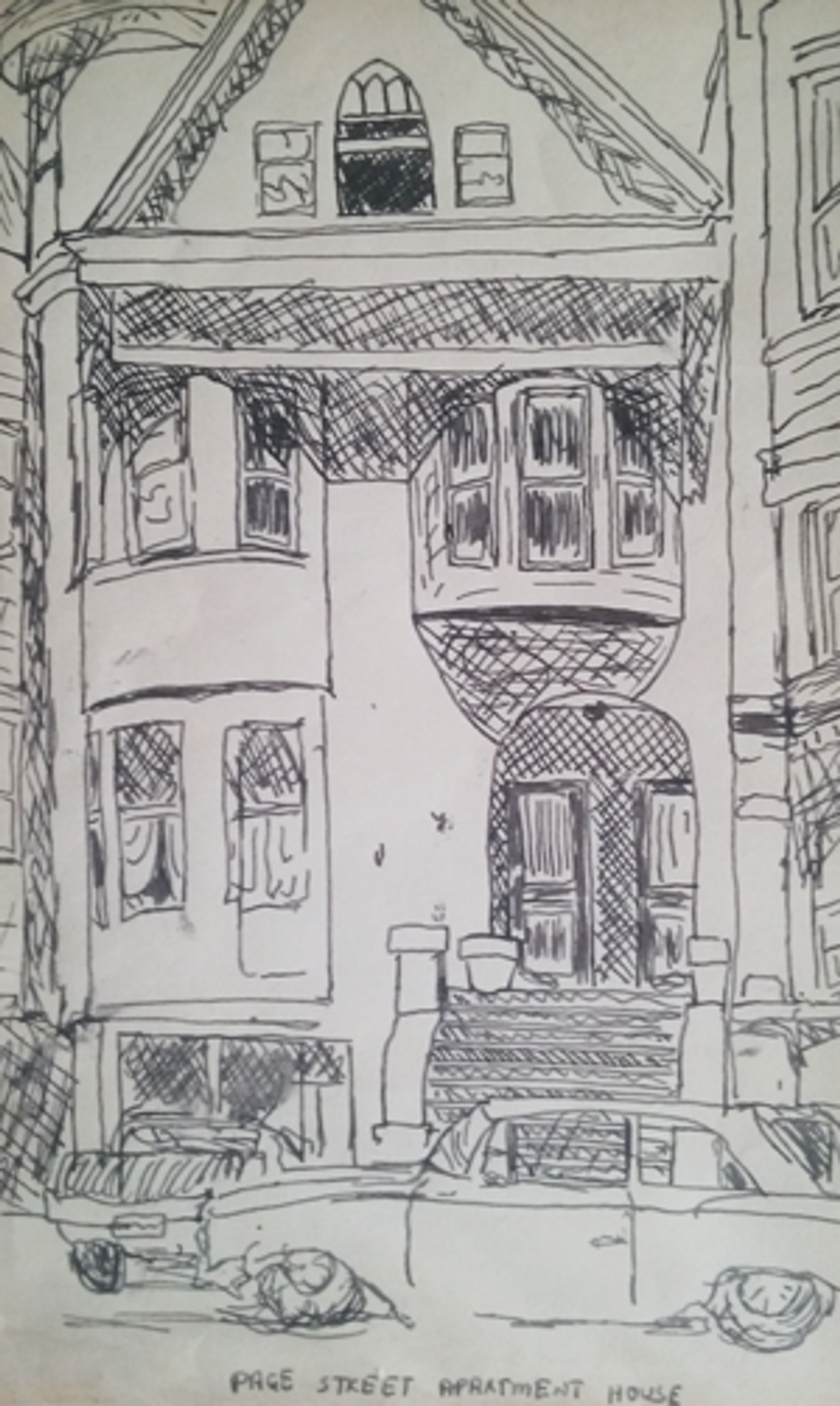

I meant to say that, in those days, having graduated high school, I was living on Page Street in San Francisco, around the corner from the intersection of Haight and Ashbury, and, every afternoon, when I got home from work, which was loading books at a book warehouse, I submerged myself in crowds that, to judge from how they dressed, appeared to have made their way to the Haight-Ashbury directly from the Franco-Prussian War, or from the Apache badlands, or from a Hindu pilgrimage, or a Mexican campesino village, or a doormen’s convention, in order to lose themselves in mystical reveries along the lines of—but what were those lines? On Haight Street I used to buy the hippiest of the hippie newspapers, the monthly San Francisco Oracle, which came out less than monthly, in order to find out. Only, the Oracle was incomprehensible. Otherwise, I would recount what was in it. Avidly I read it, though. I have noticed that I do not mind reading things that I do not understand. This is a skill I picked up in the Haight-Ashbury. It is good.

Just now, Danny Goldberg, the music producer, has published a book about the hippie efflorescence of 1967 titled In Search of the Lost Chord, which is a phrase from Sir Arthur Sullivan, wittiest of all light composers, he of Gilbert & Sullivan, but is meant to be, in this instance, mystically heavy. Goldberg was, like me, a high school graduate of 1967 and was on the scene, but, unlike me, he stayed on the scene, more or less, being a music producer and all, which multiplies his authenticity factor by a longevity factor. And, with these factors working to his advantage, he conducts a survey of the hippie universe of that particular moment, touching on the rival hippiedoms of San Francisco and New York, the philosophical avatars of LSD, the wisdom of Allen Ginsberg, the grandeur of the Grateful Dead and other examplars of the “San Francisco Sound,” the New Left radicals and black-power militants (as seen from a hippie standpoint), and the underground press—together with a few high-school reminiscences of how exciting it was for him and his friends at the Fieldston School (mini-epicenter of hippiedom in the Bronx) to cop marijuana, or to listen to hip radio shows, or to watch a schoolmate run off and marry a rock drummer, and generally to engage in the ecstasies of high-school subversiveness, than which nothing is more thrilling.

Various elements of the survey will be familiar from excellent books of long ago, written by equally authentic authors, e.g., Charles Perry’s The Haight-Ashbury (on the San Francisco epicenter) and Todd Gitlin’s The Sixties (on the leftwing aspect), classics of the 1980s. But Goldberg possesses the unusual merit of being, as it were, a two-headed freak, leftishly political and mystically anti-political at the same time. His sympathies are catholic, with a small c. Catholicity steers his analyses in the direction of nostalgic mush, now and then. LSD seems to him to have a virtue even now, which surprises me, given how much boring music, bland and droning, came out of the acid fad. Acid trips, in my experience, are themselves bland and droning. The lights throb. Things wobble. The hours pass, but not swiftly. Goldberg feels otherwise, though. He likes the music. He had better like it, given his profession.

He sprinkles his pages with the aptest of details, as in his marvelous quotation from John Selvin, the music critic: “The Summer of Love never really happened. Invented by the fevered imaginations of writers for weekly news magazines, the phrase entered the public vocabulary with the impact of a sledgehammer, glibly encompassing a social movement sweeping the youth of the world, hitting the target with the pinpoint accuracy of a shotgun blast.” This is superb, intentionally or not. Confusion about metaphors was an aspect of the scene that no one thinks to mention. And yet hippiedom was nothing if not a blazing saddle, a hydrogen jukebox, an encompassing sledgehammer. Bob Dylan was the countercultural genius because he knew how to put this sort of thing to music.

Goldberg is right, too, to recall that, back in the day, there really was a cheerful sense of ἀγάπη, a matter of gemeinschaft, virtually a קיבוץ, which hippies felt for one another spontaneously. Hippie drivers picked up hippie hitchhikers. Joint-sharing was sacramental. Only, what was the source of the solidarity? I think it was a matter of laughter in an anti-sentimental vein—a peculiar and bitter laughter, sharply hostile. Goldberg recalls that, in 1967, Ronald Reagan was elected governor of California, and said, “A hippie is someone who looks like Tarzan, walks like Jane, and smells like Cheetah.” Hippiedom was a mass recognition that even the rhythm of Reagan’s joke was appalling. Hippiedom was a shudder of revulsion at the cloying fakery of that kind of joke. It was a revulsion at the sentimental assumptions, a revulsion at the self-satisfaction—a wise and knowing revulsion, above all, at the horrifying odorlessness. Hippiedom was the wrath of Cheetah.

Paul Berman is Tablet’s critic-at-large. He is the author of A Tale of Two Utopias, Terror and Liberalism, Power and the Idealists, and The Flight of the Intellectuals.