My Grandfather’s Love Songs

A visit with Georges Moustaki, whose ballads are an epitaph for the French-speaking Jews of the Middle East

I recognized his voice the moment I heard it. Calm, slightly accented, indolent but melodious, ever so baritone, and though nearly 30 years older than it was on the tracks I knew so well, it was undeniably the voice of Georges Moustaki. I grew up listening to the Jewish-Egyptian French-speaking songwriter with my Alexandrian grandfather, who died during my senior year of high school. It was for that reason that when Moustaki called my room in Paris I could picture him on the other end of the line—graying hair tousled by the wind, linen trousers, a sardonic but charming grin. At once it felt like I was talking to someone I had known all my life and as though I was listening to an old familiar recording.

Several days earlier I had begged the French editor of my book—also a well-connected editor at Le Nouvel Observateur—to help me contact him. Although she hesitantly agreed, she also confessed that she did not know the right people and that it didn’t seem hopeful. Forty-eight hours later, she sent a note to inform me that after a great deal of work she had finally been able to come through for me. So, there I was, at 11 at night, gracelessly strumming an antique guitar, when Moustaki called. “Look,” he said. “I’m tired right now, but why don’t you come by next Tuesday at 5?”

Today Georges Moustaki is one the last living French folk songwriters of the 1950s to 1970s, known as chansonniers; these musicians were often classically trained and wrote highly literary and poetic lyrics. His story also epitomizes the journeys and trajectories of a very large population of Mediterranean Jews who found themselves in Alexandria, the cosmopolitan port city that offered trading opportunities, economic prosperity, and perhaps most important, the European culture the former colony still maintained. Moustaki and his family, like mine, and like many other Mediterranean Jewish families, spoke French. In the late 19th century a group of influential Parisian Jews came together and founded the Alliance Israélite Universelle, whose mission was to educate and advance Jews in the Middle East by exposing them to the French language and French culture. There was, however, a second and perhaps unanticipated effect on Jews like Moustaki: Even though they did not have French passports or French ancestry, they felt a nagging and inexplicable pull toward France.

In many ways Moustaki was the realization of the Alliance’s goals and of cultured, Middle Eastern Jewish ambition. He came to France and wrote songs for Édith Piaf and quickly gained success as a French singer and songwriter. At first he may have admired Jacques Brel and Georges Brassens—whose first name he took as his own—but he was soon able to join their ranks. He could fill a café by showing up only 15 minutes beforehand; he packed stadiums and traveled extensively. At no point in his career did Moustaki lack a group of fans who were not only dedicated to him and to his songs, but who were also young. Only in 2009 did he have to stop playing concerts, and that was because of his health.

However, despite living in France, speaking and writing primarily in French, and feeling a profound love of France and of French culture, Moustaki still felt like an outsider. His muddled family origins, and his alienation from actual Egyptian culture as a result of a francophone environment, made him and other Alexandrians anti-cosmopolitans in the deepest sense; the varied nationalities of these Mediterranean Jews didn’t make them citizens of everywhere, but rather, citizens of nowhere. Moustaki says this himself in one of his songs: Je ne suis pas d’ailleurs, je ne suis pas d’ici. “I am not from elsewhere, I am not from here.”

The unusual sensation of being from nowhere is what made Moustaki stand out among the French songwriters of the ’60s and ’70s. In what is perhaps his most famous song, “Le Métèque,” he amalgamates all his various personas—the Mediterranean Gypsy, the wandering Jew, the Greek shepherd, the vagabond—and romanticizes them. Moustaki took what seems in other songs to be a painful part of his identity and turned it into a charming personality trait. With this song Moustaki became the voice of French-speaking Middle Eastern Jews.

***

I arrived early to his apartment on Île Saint-Louis and wandered outside for a quarter of an hour. I tried to come up with conversation topics beyond the initial and bromidic what an honor to meet you, or I can’t believe I’m finally here. I wanted to have something substantial to say, I wanted to impress him, or in short, I wanted him to remember me. But what could I possibly say? I couldn’t talk about how things used to be in Alexandria, because I had never even been to Egypt. I couldn’t tell him a joke in Arabic the way my father or grandfather might have been able to. All I could think of was to ask if he had bought his bicycle at my great-grandfather’s store, which was the biggest in Alexandria.

“Do me a favor,” he said. “Anything,” I told him. He stopped to think, and finally spoke again: “Never, never, smoke. Promise me.”

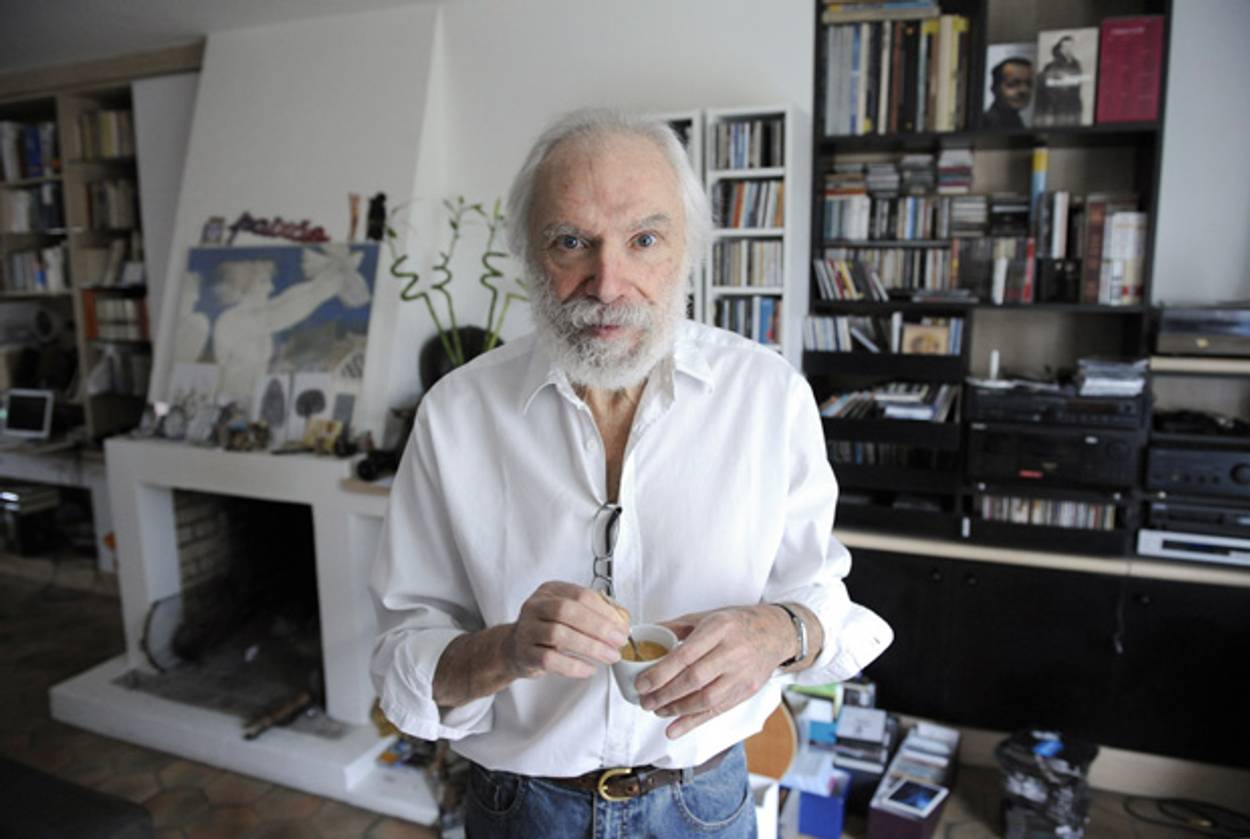

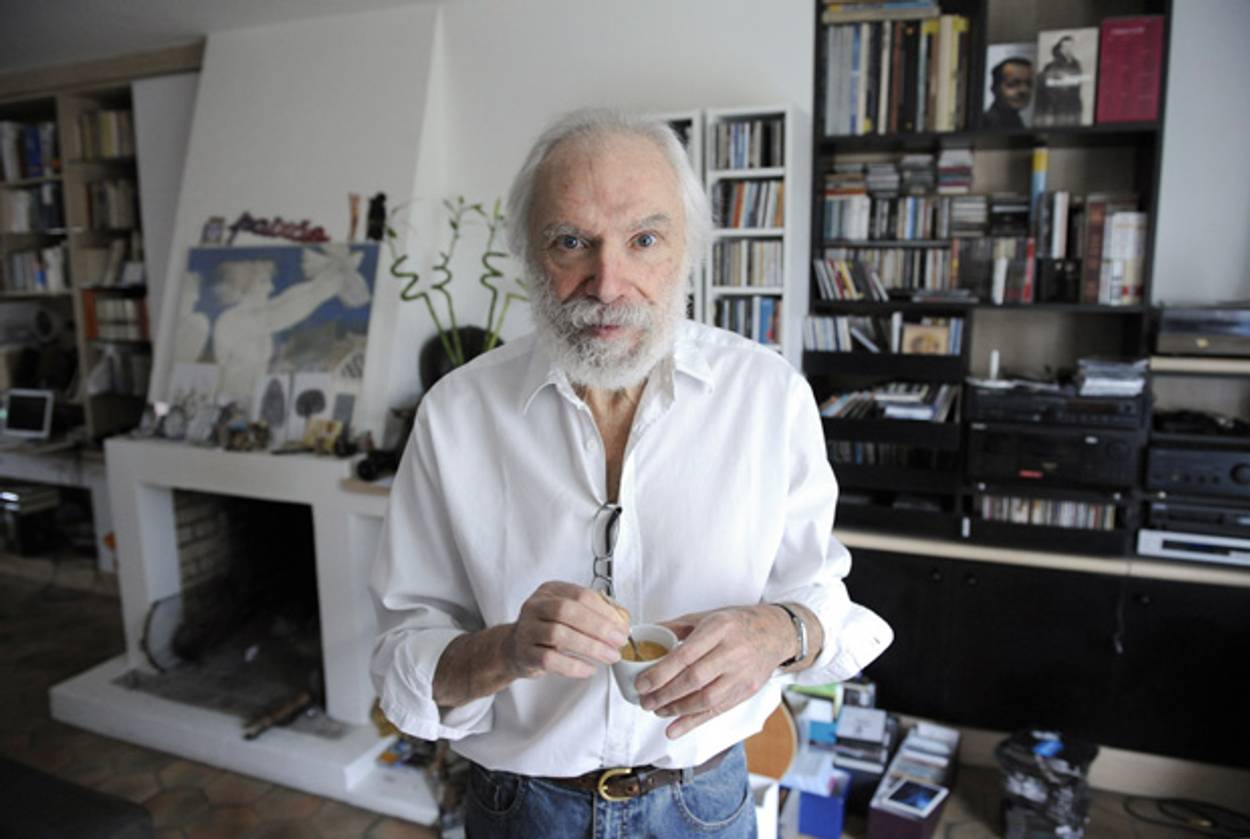

When I finally entered his apartment, his housekeeper told me he was very tired. He was hooked up to an extensive breathing apparatus—as I am sure were many other Gitanes-smoking French musicians of his generation. Although he was sitting slouched over on his couch, which faced a large wall of windows through which you could see the Parisian skyline, I could tell that when standing he was a tall, even imposing person. His hair was white, but still as long as on his album covers, his eyes were the same grayish tint of my grandfathers’. His apartment was a real atelier—a studio, with countless guitars suspended on the walls, ouds and balalaikas leaning against pillars, stacks of scorebooks, and a black grand piano in the corner of the room near the window. The corridors were lined with works of art and also some of Moustaki’s own paintings. “I have a show of my work in the summer,” he said, on catching my eye canvassing the walls, as I took a seat with my back to the window.

Sitting before me was Georges Moustaki, the greatest Alexandrian, greater for Alexandrians even than Alexander himself. I was, quite simply, starstruck. “Would you like a coffee?”he asked me. My immediate reaction was to tell him I didn’t drink coffee. But instead I paused. “You do, after all, want to have a coffee with me, don’t you?” he repeated. Of course I did.

“Did you buy your bike at Yerouchalmi’s shop in Alexandria?” I finally asked, at a loss for anything else to say. As it turned out he enthusiastically remembered the shop and had read my father’s book. Moustaki spent a good deal of my visit telling me about being from Alexandria and how it had changed—a super-highway bridge was planted over the city’s famous crescent-shaped coastal beach, and nobody spoke French there anymore. He wanted to make sure I knew what to expect in case I ever decided to go and see Alexandria for myself. He asked me questions about what I liked to do, my writing, how I learned to write, and what I planned to do with my time in Paris. Finally he told me about going to Brooklyn as a young musician to meet Henry Miller, whom he loved, and how seeing me, a writer in Paris coming to visit him, reminded him that finally his role with Miller had been reversed.

It was now his turn, he said, to be the tired mentor. Indeed he seemed fatigued, and his housekeeper came to check to see if his air supply was attached correctly. “Do me a favor,” he said. “Anything,” I told him. He stopped to think, and finally spoke again: “Never, never, smoke. Promise me.”

Perhaps the Alexandrian in him saw in me a small portrait of this recent ancestry, a sliver of the old world mixed with the new. He wouldn’t go on until I promised him that I would never smoke, and he finally gave me a warm, avuncular smile of approval. Then he told me what it was like coming to Paris and starting out as a piano-bar musician, and how one night after seeing Brassens play, his hobby became a passion. He told me about his friendship with Édith Piaf, and how he was responsible for writing “Milord,” and that she helped promote him and push his name around Paris. He confessed that Gainsbourg was an ugly man and a terrible bore. He told me about Barbara, another French singer who was also a Jew and with whom Moustaki collaborated many times over the years. He explained to me that her personality on occasion seemed particularly dark, but that she was always tender.

But he became very wistful when I asked him about a late friend of his, another great songwriter, Serge Reggiani. He played me a recording he and Reggiani made together of one of Moustaki’s own songs, “Ma Solitude.” He pointed out how well they harmonized. Beside Reggiani’s French voice, Moustaki sounded Parisian, but vaguely foreign. This may have been my own projection. Moustaki was the last of two dying breeds—the classic French chansonnier, and those who had seen and loved Alexandria in its former glory.

Although most of my fellow students in Paris enjoyed going to nightclubs and listening to popular music, I was becoming a student of the French chansonnier. This extinct breed of musician used only pianos and nylon-stringed guitars, wrote lyrics that clouded any line between popular music and poetry, and made sure that their voices strayed as far from actual singing as possible. Instead, they spoke lyrically and with only a vague inflection of melody. Moustaki had taken this trope and embraced it but cast it ever so delicately in a new light. Instead of writing about a particular woman—usually a prostitute—as the French singers did, Moustaki wrote about love in a way that was far more ambiguous and, as a result, far more poignant.

The Alexandrine influence on Moustaki’s chansons is particularly clear in his song “Le Temps de Vivre,” or “Time to live,” which is about taking time from one’s life for love. He didn’t write about the banks of the Seine in Paris, he wrote about the Mediterranean wind in the summer, and how ancient each wave is, and how poetic the Alexandrian waters are. He didn’t write about good booze, or a bustling cabaret in the 6th, but about more exotic ideas. He wrote about how his grandfather who spoke only Greek didn’t understand him.

In one TV interview he plays “Le Temps de Vivre,” wearing all white and with a small array of flute players behind him. The suited and pristine French announcers simply do not know how to react. Moustaki took his various influences and patched them together so that they had no single, traceable origin; they came from everywhere, and from nowhere. France did not need another Brassens, but it welcomed and adored Moustaki, perhaps because nobody could put their finger on the man who came to cabarets with his nylon-stringed guitar but sang about something entirely different. Moustaki approached the idea of the chansonnier like a native because he was able to effortlessly adopt its technique and form, and yet at the same time his Mediterranean regalia and unusual songs made him so decidedly a foreigner.

As the recording of him with Reggiani ended, he confessed that he couldn’t quite play guitar the way he used to, but was trying to readjust the way he played chords. He told me to go pick up one of the many guitars that were in his apartment and to hand him the one sitting on the piano. He wanted to show me the chords to “Ma Solitude,” a song about how one’s solitude is perhaps one’s most loyal companion through life. Slowly he walked me through the major and minor chords, almost as though he wanted me not only to know them, but as though he wanted me to remember them once I left his apartment. I knew nobody in my family would believe me if I told them what had happened. We had used each other to draw up an affection for something that was, for him, long gone, and that in my case never really existed to begin with. My inelegant guitar playing didn’t seem to bother him, perhaps because right then all that mattered was the pleasure of being two pseudo-Franco ex-Alexandrians, playing guitar together.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Alexander Aciman is a writer living in New York. His work has appeared in, among other publications, The New York Times, Vox, The Wall Street Journal, and The New Republic.

Alexander Aciman is a writer living in New York. His work has appeared in, among other publications, The New York Times, Vox, The Wall Street Journal, and The New Republic.