Lou Reed’s Rabbi

The rock star’s new tribute to his teacher, the writer Delmore Schwartz, illuminates their common genius

This piece was originally published on October 29, 2012. Lou Reed died Sunday.

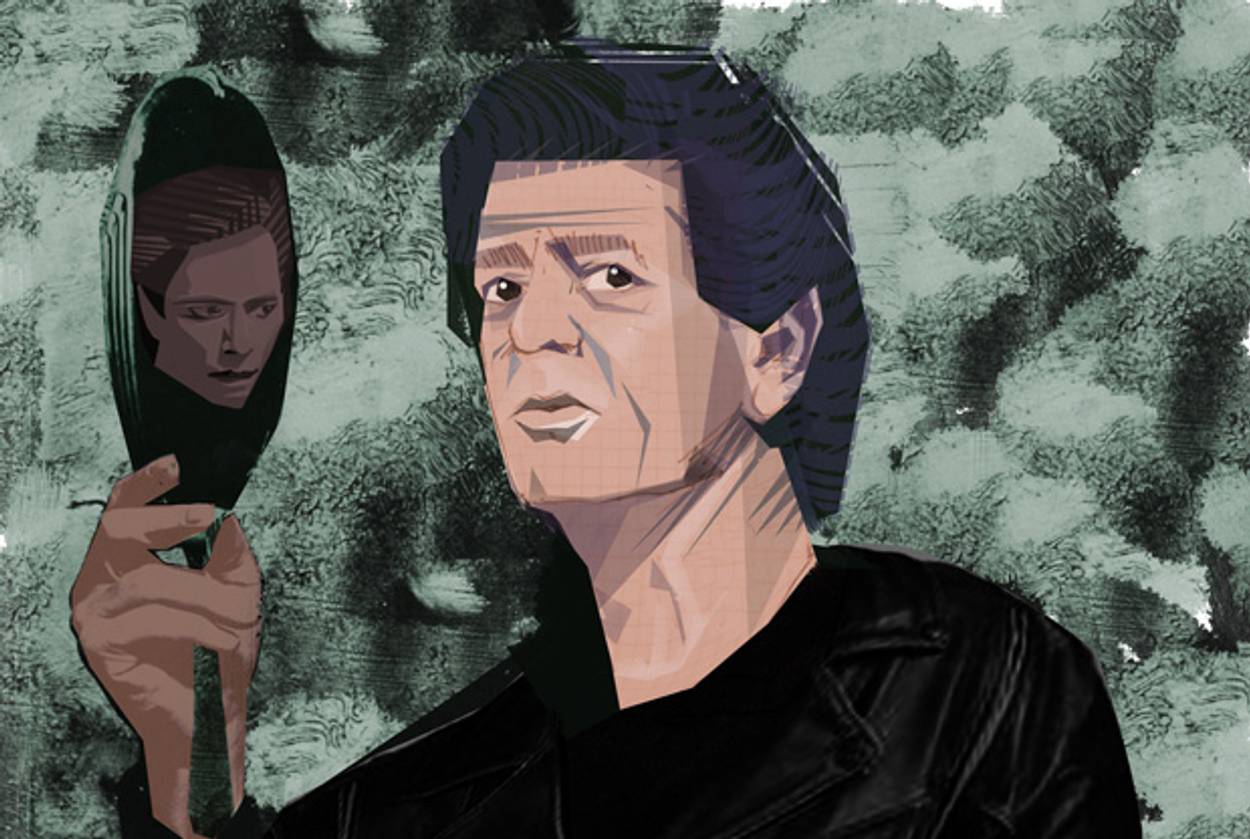

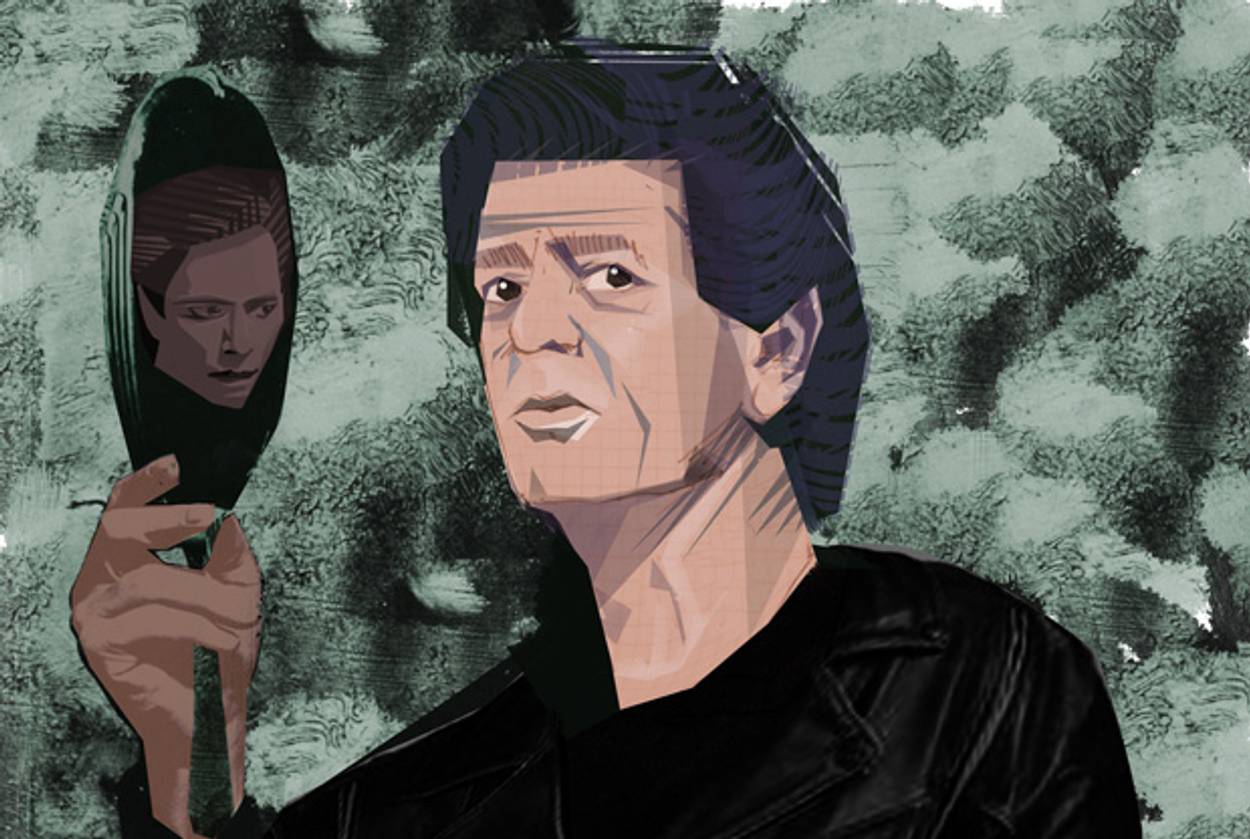

Lou Reed is the indelibly hip version of Woody Allen’s Zelig: A human chameleon continually and thoroughly transformed by his surroundings. The difference, of course, is that while Allen’s film character grotesquely altered his physical appearance and worldviews so he would be liked, Reed’s radical shifts have been determined by desire to duck expectations, to shake up and subvert established forms of normalcy. As an iconic rock star, Reed has lived out his numerous rebirths and in the process popularized if not outright invented a number of musical genres—art-rock, avant-pop, noise, and punk, among others.

What remained constant throughout his transformations, however, is Reed’s rootedness in literature. His lyrics have always been filled with references that ranged from Shakespeare to the Marquis de Sade, from Edgar Allan Poe to James Joyce. And now, after over half a century of bona fide writing and composing, Reed has penned a piece that is among his very finest bits of writing to date—an introduction to the New Directions reissue of Delmore Schwartz’s collection of short stories In Dream Begin Responsibilities.

Schwartz, a star of the New York literary scene in the 1930 and ’40s, was a poet, innovative prose writer, cultural critic, and, at one time, a professor of English literature at the University of Syracuse, where Reed met him in the early 1960s. As is clear from the introduction to In Dream Begin Responsibilities, Schwartz’s impact on Reed’s life has not waned one bit over the years: “You were the greatest man I ever met. … Your titles were more than enough to raise the muse of fire on my neck.” Lovingly Reed recollects: “We gathered around you as you read Finnegans Wake. So hilarious but impenetrable without you. You said there were few things better than to devote one’s life to Joyce.”

Reed’s piece surges from descriptive to lyrical, from poetry to prose. At times reminiscent of Allen Ginsberg “Kaddish”—another epic tribute—Reed’s elegy is a tragicomic stream of consciousness and ecstatic excavation of memory: “Reading Yeats and the bell had rung but the poem was not over you hadn’t finished reading—liquid rivulets sprang from your nose but still you would not stop reading. I was transfixed. I cried—the love of the word.” The usage of em-dashes, as in Ginsberg’s work, intensifies the potency of the free-associative leaps. The incisiveness and vividness of the portrayal are tremendous: “Some drinks later—his shirt undone—one tail front right hanging—tie askew—fly unzipped. Oh Delmore. You were so beautiful. Named for a silent star dancer Frank Delmore.”

And then pure poetry: “Oh Delmore—the scar from dueling with Nietzsche.”

As Reed alludes, Schwartz’s genius existed side by side with his self-doubt and self-destructiveness—something that is also clear from Saul Bellow’s thinly veiled roman à clef Humboldt’s Gift (Bellow was another one of Schwartz’s outspoken admirers and protégés). “Doomed” is how Reed puts it. Indeed, Schwartz died tragically at the age of 52, by then entirely outside of the spotlight, alone in a hotel room, in the throes of alcoholism and depression.

The new edition of In Dreams Begin Responsibilities also comes with an afterword written in 1978 by Irving Howe, who cast Schwartz in a vastly different light. To Howe, Schwartz’s writing emerges at the “point where intellectual children of immigrant Jews are finding their way into the larger world while casting uneasy, rueful glances over their backs.” Howe, like Saul Bellow and other such first-generation American Jewish intellectuals, were so affected by Schwartz’s work because it spoke “of Brooklyn, Coney Island, and Jewish immigrants fumbling their way into the new world, but also of their son, proudly moving toward the culture of America and finding there a language for his parents’ grief. … Schwartz had found both voice and metaphor for our own claustral but intense experience. … We heard a voice that seemed our own, though it had never really existed until Schwartz invented it: a voice at home with the speech of people not quite at home with English speech.” Reed’s mysterious, brilliant professor, the procurer of Western civilization’s greatest secrets, was, according to Howe, above all, the progenitor of writing on the American Jewish experience.

While Schwartz’s poetry and cultural criticism covered a fairly wide range of subjects and perspectives, in his short stories, which Reed introduces in this volume, Schwartz inevitably returns to his roots, his family, and other families like his, ill-fitting Jews with big dreams, with one foot on American soil and another still dangling in transition.

One can’t help but wonder why Reed does not broach the ethnic connection between himself and his mentor. Then again, Reed has never been the one to bring his ethnicity into art—certainly not in an explicit manner. There is, of course, “Harry’s Circumcision” (1992), an eerie spoken-word number about a man suddenly taken over by self-loathing that erupts when he notices his facial features bearing too much resemblance to those of his parents. The song ends with an act of self-mutilation (alluded to in the title) and a pathetically failed suicide attempt. Perhaps this is an identity piece—and yet, given all of Reed’s guises and transformations, it can’t be the definitive one.

In whatever way it may have affected his work, Reed’s Jewishness has remained mostly an unnamed, elusive factor. And what speaks louder to this elusiveness than this introduction to Schwartz’s collection, which does not dwell on the specifics or circumstances but traces a certain universal trajectory in Schwartz’s destiny and in his writing? What Reed absorbed from Schwartz’s work was not quite the ethnically specific content and scenes but a larger tendency and methodology. Each of Schwartz’s stories spins cinematically, zooming in and out of the social landscape Schwartz chooses to focus on. With next to no plot, the stories gradually uncover the inner lives of their characters, treating readers to exquisite sarcasm, philosophical ramblings, and memorable—often profound—quips and insights. If Voltaire and Nietzsche met and sat gossiping on Brighton Beach boardwalk, they’d probably sound a lot like Schwartz. And in fact, some of Reed’s most popular songs have a very similar feel: “Take a Walk on the Wild Side,” “Sweet Jane,” “Wild Child,” and “Hangin’ Around,” among numerous others, weave together biting, slightly abstract, at all times entertaining, (a)moralistic bits of social commentary. Whereas Schwartz wrote about Jewish immigrants and their children, Reed described the world (or rather, underworld) of the counter-culture to which he belonged.

The attempt to read Schwartz’s overtly Jewish worldview through a universal lens isn’t new to Reed. A half-century ago on Velvet Underground’s first album, he put forth the first tribute to his mentor, by dedicating the record’s final track to him—“European Son (To Delmore Schwartz).” The track went down in musical history as one of the band’s most experimental: After a few cryptic verses, the song launches into a long frenzied improvisation, complete with a loud crash of a pile of plates. Hypnotic and unnerving, the song engenders an inner state wrought with unsettled, directionless intensity. If there’s anything that’s clear, it is a sense of a severe generational conflict: “You killed your European son/ … / You made your wallpaper green/ You wanted to make love to the scene/ Your European son is gone.”

In a short story “America! America!” describing a moment of disassociation from the immigrant Jewish community and his family, Schwartz evokes a character who views his relatives, the older generation, with much “irony and contempt,” and from “such a distance that what he saw was an outline, a caricature, an abstraction.” And yet, amidst identity vertigo, he confesses to having “felt for the first time how closely bound he was to these people. His separation was actual enough, but there also existed unbreakable unity. As the air was full of the radio’s unseen voices, so the life he breathed in was full of these lives and the age in which they had acted and suffered.”

Reed belonged to an entirely different era than Schwartz, and his concerns were also different. In a cautious, self-deprecating manner Schwartz examined the extent of his circle’s belonging in the wider American culture; he felt too haunted to fit in. Reed emphatically rejected normative Americanness and any notion of fitting in. What united teacher and student, then, was a constant social disorientation and dissatisfaction, the spirit of wandering and rejection. They both found themselves listening to what Schwartz referred to as those “unseen voices” and channeling them. In yet another song, written in Schwartz’s honor—“My House” on the “Blue Mask” album of 1982—Reed describes the deceased Schwartz as being “at peace at last, the wandering Jew” and imagines him occupying an empty room in Reed’s own house—“a spirit of pure poetry/ is living in this stone and wood house with me.” And to anyone thinking the word choice of “spirit” accidental, Reed then describes how he and his then-wife summoned his mentor with a Ouija board.

Given the depth of their respective existential crises, their perceptions laden with “unseen voices,” and all the transformations Schwartz and Reed respectively witnessed—personal, generational, ethnic—the metaphor of the supernatural does not seem terribly far-fetched. It fits right in with these two life stories, fraught with fantastic subterranean connections that belong equally to American Jewish history and to the mythology of American music and literature. How can one ever listen to Reed’s music or read Schwartz in quite the same way, after encountering the final lines of Reed’s introduction to In Dream Begin Responsibilities, in which the singer addresses his mentor: “I wanted to write. One line as good as yours. My mountain. My inspiration.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Jake Marmer is Tablet’s poetry critic. He is the author of The Neighbor Out of Sound (2018) and Jazz Talmud (2012). His jazz-klezmer-poetry record Hermeneutic Stomp was released by the Blue Thread Music in 2013.

Jake Marmer is Tablet’s poetry critic. He is the author of Cosmic Diaspora (2020), The Neighbor Out of Sound (2018) and Jazz Talmud (2012). He has also released two jazz-klezmer-poetry records: Purple Tentacles of Thought and Desire (2020, with Cosmic Diaspora Trio), and Hermeneutic Stomp (2013).