Likeness of a Jew

A dispute between novelist Alan Hollinghurst and author Daniel Mendelsohn revives a history of sensitivity to British stereotypes about Jews

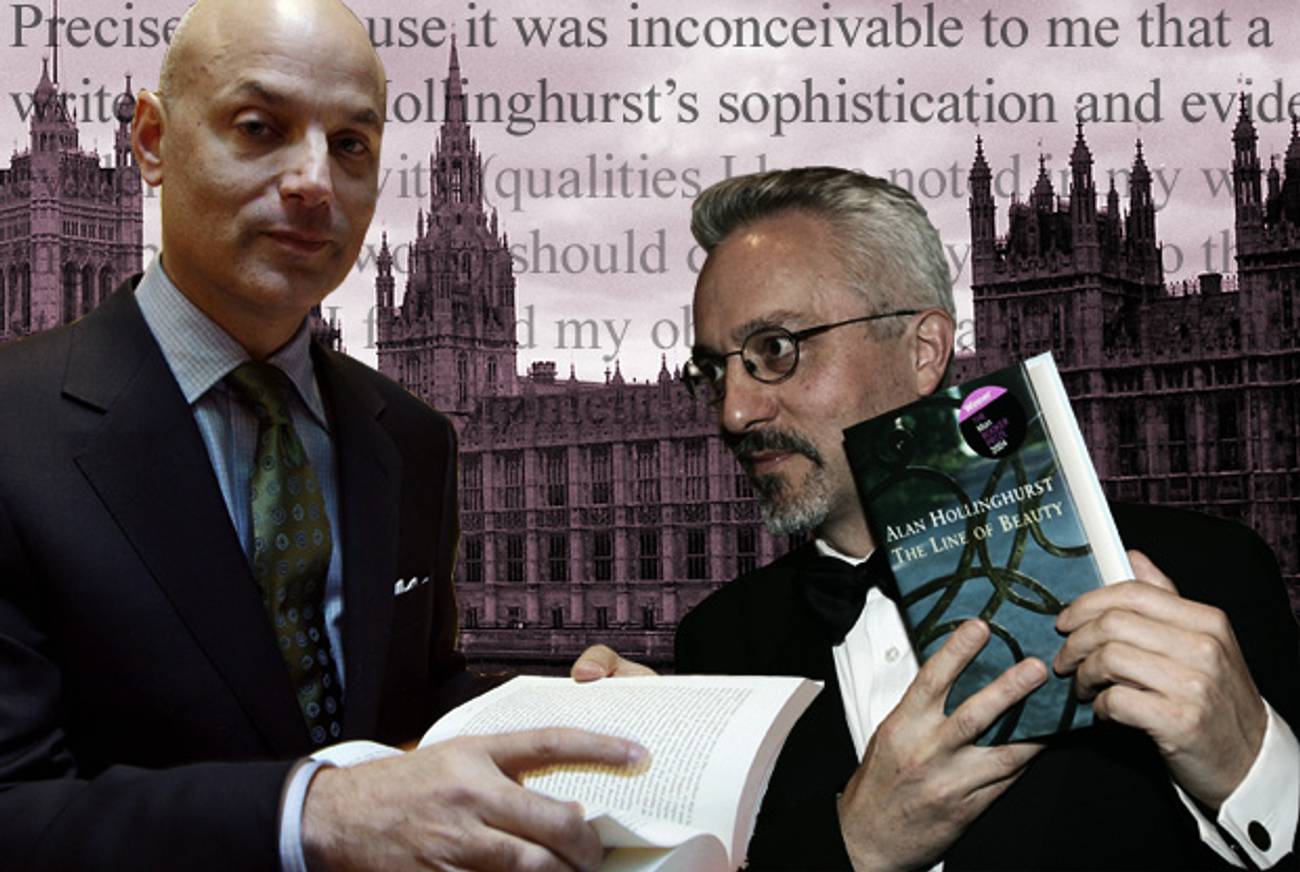

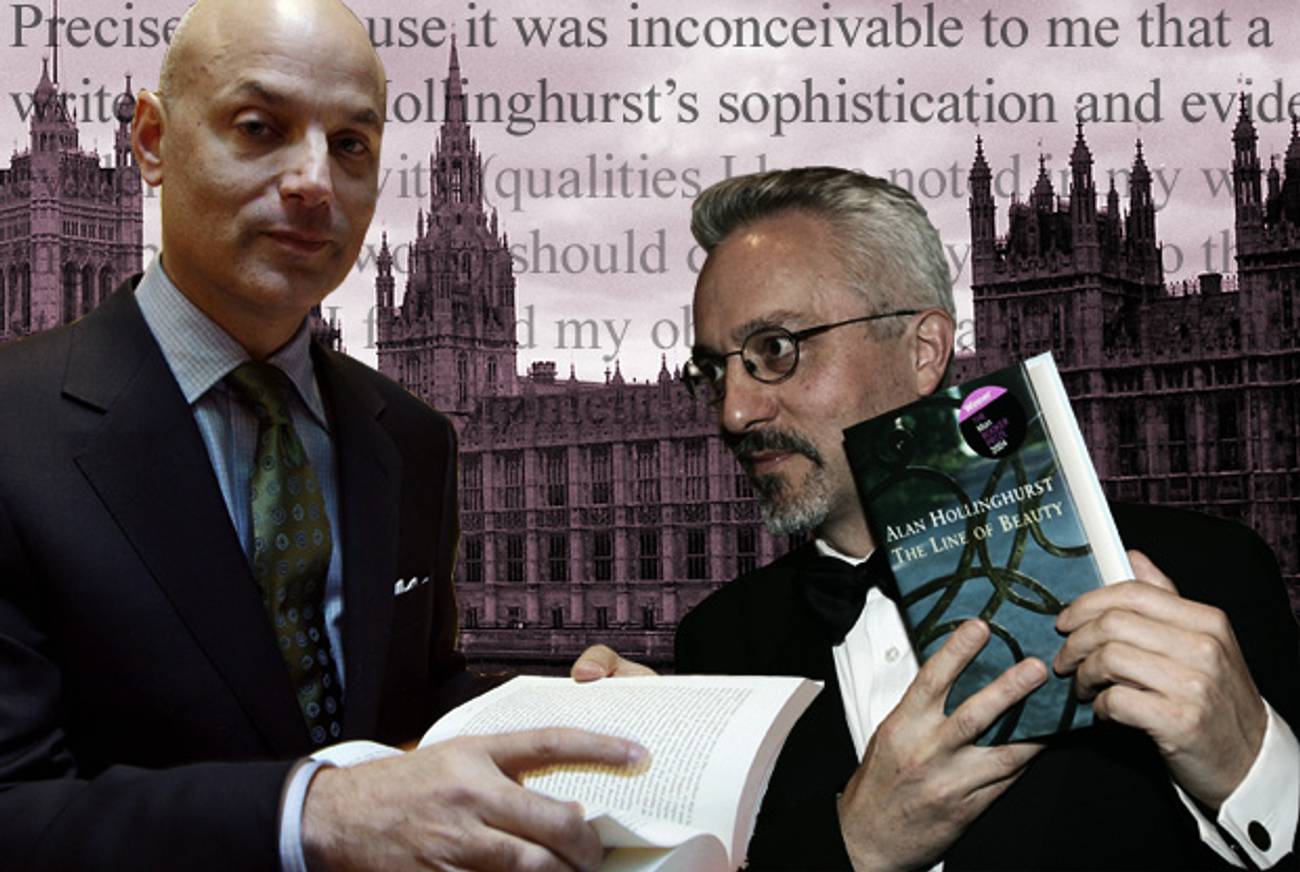

In our age of promiscuous communication, an old-fashioned war of words in the New York Review of Books reminds us that even language at its most civilized can bear a sting. In November, author Daniel Mendelsohn, a classics scholar and, increasingly, a public intellectual, published a 5,000-word essay on the oeuvre of English novelist Alan Hollinghurst, winner of the prestigious Man Booker prize for The Line of Beauty (2004), a portrayal of Thatcher-era England. Hollinghurst’s current book, The Stranger’s Child, was the occasion for Mendelsohn’s assessment of the novelist’s career. It did not go down well.

The Mendelsohn-Hollinghurst dispute will not make Page Six (as Gore Vidal v. Norman Mailer might have), but it retains a potential for damage in the world of Anglo-American letters. At the center of the dispute is the imputation by Mendelsohn that Hollinghurst has the “unconscious inclination” to “lapse into an old British literary habit”—using Jewish characters as markers of un-Englishness and social decline. Let’s be clear: Nowhere does Mendelsohn overtly accuse Hollinghurst of anti-Semitism or intentional anti-Jewish bias. Instead, he asks, “What, exactly, are we being asked to conclude about the crass ‘new’ England [in Hollinghurst’s The Line of Beauty] when we learn, of one member of [protagonist] Nick Guest’s new circle, that the grand Duchess of Flintshire was once ‘plain Sharon Feingold’?” Mendelsohn raises a question and lets the reader ruminate on its implications.

That said, Mendelsohn’s overall assessment of Hollinghurst’s career is often generous and complimentary, as when he discusses the author’s debut success from 1988, The Swimming-Pool Library, “in which a plush style, a formidable culture, and a self-confident avoidance of then-fashionable formal tricks were put in the service of a startling direct and unembarrassed treatment of gay desire.” But that Mendelsohn saw fit to raise this Jewish issue at all—late in the review and in no more than a few hundred words—has proven small comfort to Hollinghurst. In the subsequent Dec. 8 issue, Princeton’s Galen Strawson, the British philosopher and literary critic, lodged a vigorous defense, in which he chastised “a usually intelligent critic like Daniel Mendelsohn” for using as evidence against Hollinghurst a series of minor characters with Jewish surnames “to indicate any trace of anti-Semitism” and for “a failure of ear, a narrowness of mind, an ignorance of the world, a capacity for unwarranted insult.” Strawson ended his missive with the stirring prescription that “Mendelsohn should apologize unconditionally for a slur that is as serious as he himself takes it to be.”

In fact, there was no stated slur, yet in Mendelsohn’s original critique there is reference to several Jewish personae in Hollinghurst’s fiction—used, he believes, to symbolize a decline in the halcyon British brand. Thus, Mendelsohn writes “not without dismay” that in The Stranger’s Child “the irritating photographer who plagues the Valances—he represents the distressingly crass ‘modern’ world of publicity and celebrity—is called Jerry Goldblatt.” This, in a footnote. It would wait for the Jan. 12 issue of the New York Review for Hollinghurst himself to weigh in on what he calls Mendelsohn’s “poisonous atmosphere of suggestion.”

***

Certainly, to understand this fracas, we need to understand what “old British literary habit” Mendelsohn is talking about—a habit I expand to include American examples, since English traditions served ours. We are tempted to reach as far back as Shakespeare’s Shylock, the original avaricious Jew, but while the embittered Venetian money-lender makes an indelible impression seeking his “pound of flesh,” at least the Bard allows the old man to voice his grievance against the abusive Christian world in which he is fated to play his part. Still, abusive Shylock became red meat for English actors and audiences over centuries. In Charles Dickens’ early success, Oliver Twist, Fagin the Jew is introduced from the start as a version of the Devil, with his “matted red hair,” a “toasting fork in his hand,” and a “villainous-looking and repulsive face.” He leads adolescent boys down a dirty primrose path toward the rankest thievery. Cunning mixed with a measure of seduction infuses Fagin with a vaguely pedophilic quality—a twist on medieval notions of Jews drinking the blood of Christian children.

After Oliver Twist was published serially from 1837 to 1839, it would take 25 years for Dickensto be called out by a woman of his acquaintance, Mrs. Eliza Davies, for the “great wrong” he had done to a “scattered nation.” Fagin, she fears, “admits of only one interpretation.” Dickens, she proposes, has the opportunity to atone for this great wrong.

Although a Victorian of social sympathies, Dickens could not immediately see her objection; he was portraying a particular criminal type who was “invariably … a Jew.” Yet Dickens made amends in Our Mutual Friend (1864-65) with the character of Riah, described by critic John Gross as a “wholly innocent scapegoat … an involuntary front man for his non-Jewish employer, the odious Fledgeby.” More significantly, when Dickens revised Oliver Twist in 1867, he eliminated many references to “the Jew” Fagin, instead using the character’s name or a simple pronoun. Alas, Dickens felt forced to make a non-literary point: Not all Jews were Fagins.

Then there is the opposite case: George Eliot’s last novel, Daniel Deronda (1876), admired now as a failed masterpiece. Eliot sees Jews not as a “type,” but as people with a complex interior and spiritual life, distinct customs, and, at least in the character of Mordecai, aspirations for nationhood. The novel is divided between Deronda’s attraction to Gwendolen Harleth, the society beauty who ultimately gets trapped into marriage with a loathsome upper-class sadist, Henleigh Grandcourt, and Deronda’s affiliation with a group of London Jews, one of whom, Mirah Lapidoth, he has saved from suicide. The common complaint is that the novel’s Jewish sections are too didactic by half, while the Jewish characters—Mirah and Mordecai especially—are too good by at least as much. Indeed, Mirah is so sentimentally good she is nearly a Christian martyr, an ideal of Victorian feminine virtue. Bad-girl Gwendolen has vastly more energy and psychological depth. From a literary standpoint, Eliot’s Jews haven’t the vitality that could ever replace the fascinating evil energy of the all-too-vivid Fagin. Philo-Semitic in sensibility, Deronda remains the exception to the rule.

But from the high Victorian era onward, the literary Jewish presence is carved from a similar mold by even the most trenchant writers. Anthony Trollope’s Ferdinand Lopez, in The Prime Minister of 1876—the penultimate volume of Trollope’s Palliser series—is a financial adventurer who wins the heart of a proper English girl whose conservative family refers to him as a “foreign cad” and a “greasy Jew adventurer out of the gutter.” In his favor, he is handsome (although swarthy), well-educated, multilingual, and has the external manners of a gentleman. But the narrator refers to Lopez as a “man without a father, a foreigner, a black Portuguese nameless Jew,” which may or may not express Trollope’s own view—especially since the narration begins with the claim: “It is certainly of service to a man to know who were his grandfathers … and grandmothers if he entertain an ambition to move in the upper circles of society.” Trollope introduces social climbing as a major theme, yet perhaps doing so with critical irony—an irony that could well escape Jewish readers already sensitive but not inured to continuous insult.

The Jew as scheming social parvenu is a feature in Trollope’s fiction. Another fascinating financial speculator, Augustus Melmotte in the earlier The Way We Live Now (1875)—Is he Jewish? His wife is—only re-inscribes a core problem of the assimilating Other by his uncertain foreign background. The Jew of qualities who hopes to pose as the real thing—an Englishman of good breeding—disturbs the social order. As James Shapiro proposes in Shakespeare and the Jews, “The Jew as irredeemable alien and the Jew as bogeyman into whom the Englishman could be mysteriously ‘turned’ coexisted at deep linguistic and psychological levels.” If the Jew can disappear through assimilation and upward mobility, what security is there for the Englishman who has his privileges inherited as if by divine right?

By America’s Gilded Age, the grasping arriviste Jew is an unremarkable figure. In Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth (1905), a brilliant dissection of New York society, the secondary character, Simon Rosedale, smitten by protagonist Lily Bart, is, as the writer Lev Raphael sums him up, “pure anti-Semitic stereotype: unctuous, vulgar, shifty-eyed, and worthy of everyone’s contempt, even though they would love to be as rich as he is, and some society folk cultivate him for stock tips.” Raphael diagnoses Wharton’s problem perfectly: “Her portrayal … not only seems shallow, but a real break in her artistry. In relying on received wisdom about Jews, she fell beneath her own high standards.” Raphael has had his revenge, publishing a novel from the eponymous character’s point of view: Rosedale in Love.

Can anyone today misunderstand that Wharton was writing from the vantage of a woman born into an elevated New York social order that almost required the breeding of anti-Semitism in the bone? William Dean Howells, midwestern son of a politically liberal publisher, labored under no such assumptions, yet in a passing attempt to portray unreasonable prejudices against Jews in The Rise of Silas Lapham (1885)—by having the socially uncertain Laphams frankly discuss how property values fell when wealthy Jews moved into their neighborhood—the judicious Howells found himself called to account by several Jewish readers. He would cut the passage when the serialized version was printed as a book and wrote to Cyrus L. Sulzberger, editor of the American Hebrew, that “you are not the first Hebrew to accuse me of ‘pandering’ to the stupid and cruel feeling against your race and religion. … I merely recognized to rebuke it, the existence of a feeling which civilized men should be ashamed of.”

Wharton would have been incapable of such an assertion. Although rankled by the restrictions on her sex and caste, she never adopted a feminist outlook and continued to see Jews as beyond the civilized pale. In 1925, she praised as “masterly” the anti-Semitic portrait of Meyer Wolfsheim in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. Indeed, she gushed to young Fitzgerald that Wolfsheim was the “perfect Jew”—odd adjectives to apply to a shifty, physically unappealing character rumored to have arranged the World Series Black Sox Scandal of 1919.

***

A Jewish littérateur like Daniel Mendelsohn would be aware of these and lesser examples. For Galen Strawson, this awareness produces in Mendelsohn a particular prejudice, a heightened sensitivity resulting in “a capacity for unwarranted insult.” One must wonder if Strawson imagines Mendelsohn, who wrote a masterful account of family tragedy in The Lost: A Search for Six of Six Million, has no just claim to his sensitivity about Jewish representation. In his reply, Mendelsohn stands by his reading of Hollinghurst’s use of “age-old clichés of the Jew in British literature.” This was not an “ad hominem attack on Alan Hollinghurst,” he assures us, but a footnote—an “unhappy parenthesis”—in an “otherwise admiring and, I think, nuanced assessment of this worthy writer.”

When Hollinghurst finally came forward last month, he defended himself with suitable restraint, noting that where he has portrayed Jews as major characters in his earlier The Line of Beauty, “I certainly saw them as individuals just as varied, complex, and interesting as the non-Jewish characters in my novel.” And then, as if quivering with barely suppressed outrage, he wrote: “Really, I want to protest that I am a good deal more ‘conscious’ of what I am doing … than Mendelsohn … has repeatedly alleged.” At the end, he makes his most damning charge—that Mendelsohn, a literary critic, has misread the use of the press photographer Jerry Goldblatt in a “section of the book set in 1926” that was “deployed precisely to illustrate the prejudicial attitudes of Dudley Valance. … To mistake this … historical prejudice for the unconscious habit of the author is so primitive an error [my italics] as to cause some concern for Daniel Mendelsohn’s judgment.”

If this is so, then we are back to poor William Dean Howells pleading to an influential Jewish publisher that in the conversation about Jews he had put in the mouths of Mr. & Mrs. Silas Lapham, “My irony seems to have fallen short of the mark.” Strawson argues that Mendelsohn is overly sensitive; Hollinghurst asserts that Mendelsohn as critic proves incapable of distinguishing an author’s depiction of social prejudice for the author’s own views. This should be an essential skill in a literary critic but, of course, each oppressed group—women, blacks, gays, Jews—is automatically assumed to lose its objectivity when judging how outsiders portray them in fiction and film. In his attempt at a gentlemanly coda to this affair, Mendelsohn writes in reply that if “Alan Hollinghurst insists on believing that I acted out of a poisonous intent to malign him, there is little I can do to change his mind.” His “great regret” is that “this small point” will distract from his “larger critique of an author whose work … I continue to find very worthy indeed.”

Allen Ellenzweig is an arts critic. His book, The Homoerotic Photograph, was reissued in paperback by Columbia University Press in 2012.

Allen Ellenzweig is an arts critic. His book George Platt Lynes: The Daring Eye was just published by Oxford University Press.