Jewish Foreskins, Black Masks

A new biography of Frantz Fanon reminds us how the left came to prefer their Jews non-Jewish and their Blacks vocally Black

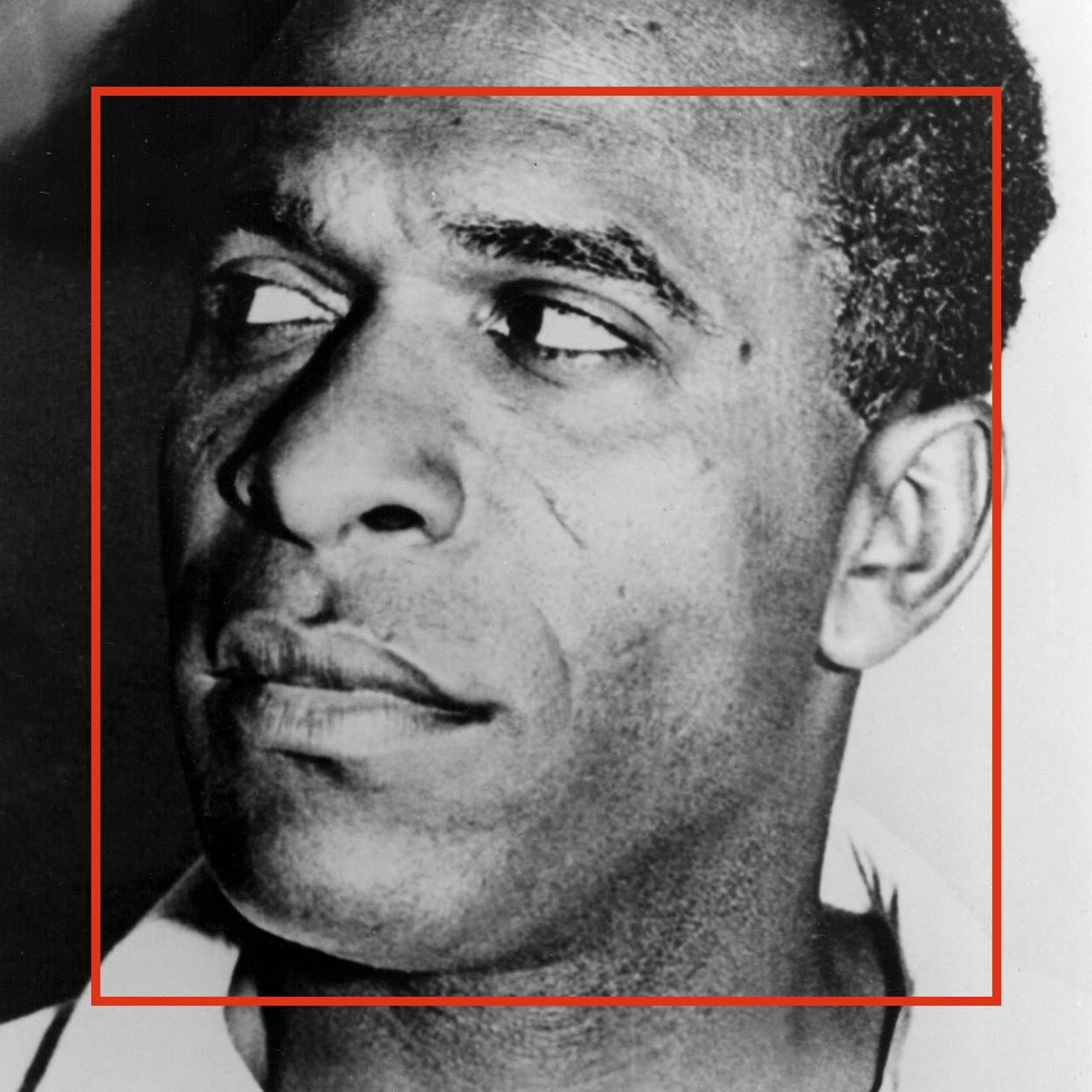

Everett Collection Historical/Alamy

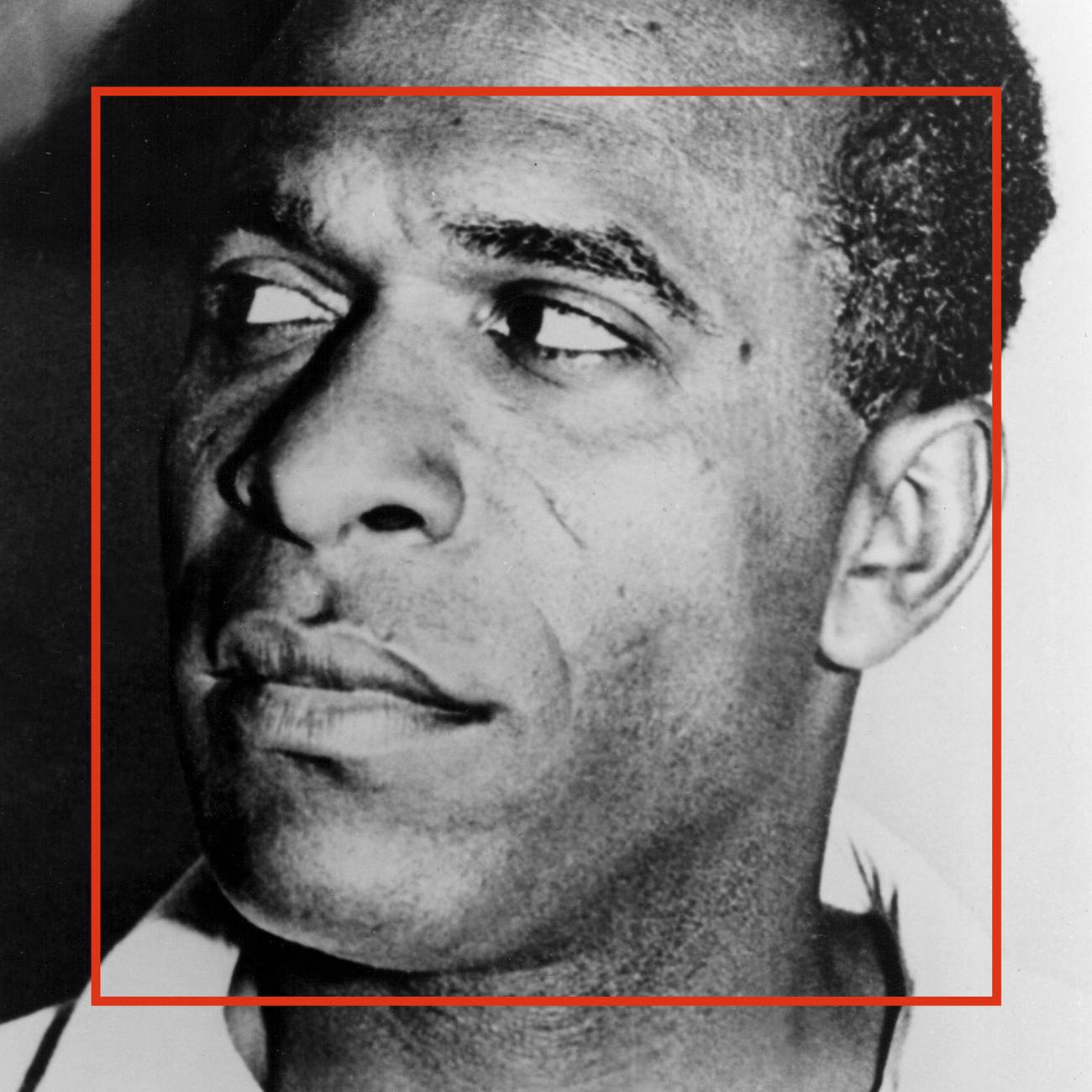

Everett Collection Historical/Alamy

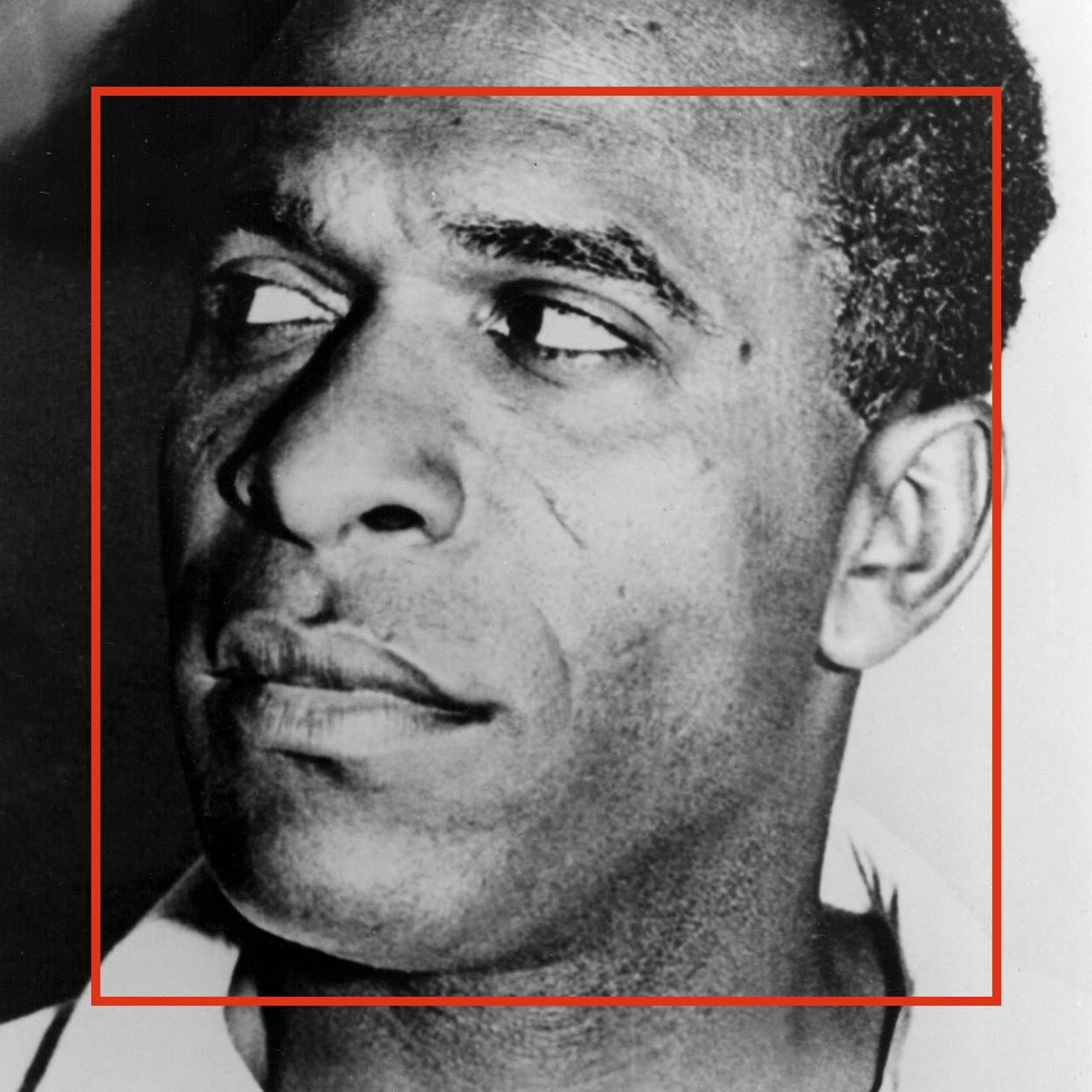

Everett Collection Historical/Alamy

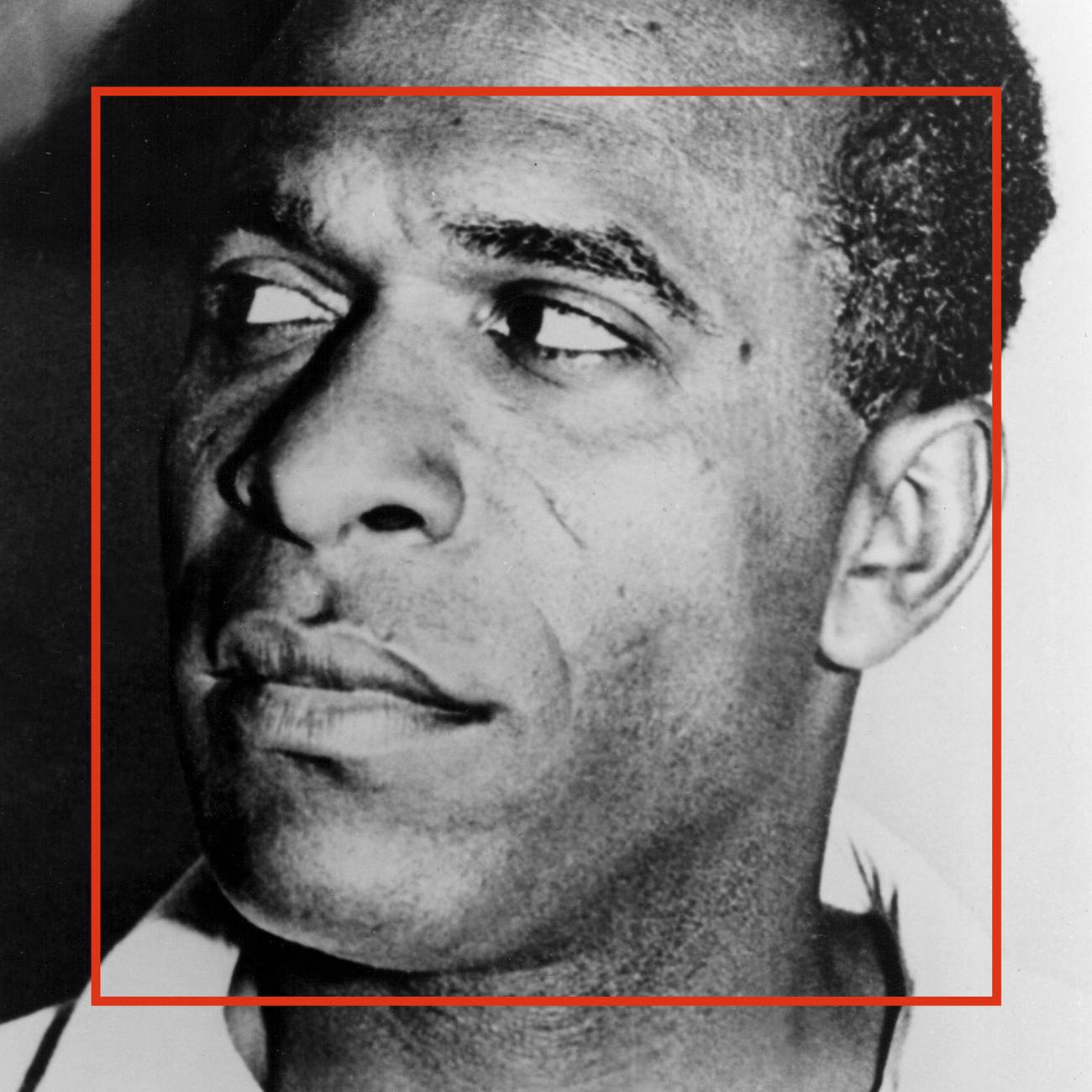

Everett Collection Historical/Alamy

Many of the attitudes and positions now casually recycled as slogans and memes were once living ideas, movingly articulated in vivid, original language by real human beings reacting to mind- and body-altering experiences, as well as powerful emotions about those experiences. They felt, thought, and fought for the articulation of their own ideas through high barriers of incomprehension, institutional inertia, fear, prejudice and outright hostility, and often under threat of grotesque violence.

A new comprehensive and capacious biography of the Martinican psychiatrist and philosopher-poet Frantz Fanon, The Rebel’s Clinic: The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon, recalls the sheer life force, courage, and steep costs required to birth anything new. Its author, the journalist and intellectual historian Adam Shatz, also incidentally makes us aware of the difference between much of the contemporary uncritical conformism and approval-seeking that costumes itself as activism, and the genuine article.

Like a high IQ Forest Gump, Fanon had a remarkable gift for finding himself on the scene at some of the 20th century’s most crucial events. He first enlisted at 19 in the Free French Forces in 1944, eager to escape the provincial “backwater of empire” of Martinique, then under Vichy control. (During his initial attempt, a misfire, he tried crossing shark-infested waters on a small fishing boat from Martinique to Dominica.) Later, he was wounded fighting Nazis in the French Alps, where he received a croix de guerre from Raoul Salan, the general who would later direct the French Army’s reprisals against Fanon’s Algerian comrades.

Back in Martinique, before returning to France to study medicine and psychiatry in Lyon, he came under the influence of Aimé Césaire, the revolutionary modernist poet of négritude and an advocate of peaceful decolonization. In Lyon, Fanon wrote bad plays, discovered the work of Sartre, Camus, and de Beauvoir in Les Temps Modernes (“Anti-Semite and Jew” played an important role in his thinking about stereotypes), and attended lectures by the philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty, whose theories of embodiment, Shatz suggests, impressed the wounded war veteran and influenced his approaches—both intellectual and hands-on clinical—to traumatic experience. Again chafing against provincialism, this time the medical profession’s, he sought out one of institutional psychiatry’s great radical reformers, Francois Tosquelles, who introduced him to his pioneering practices of mental health treatment: Inmates had a substantive role in running the asylum—growing their own food, organizing their own cultural events, and participating more or less as equal partners in their own treatment.

Rusticated to a clinic in Blida, Algeria, Fanon put his own spin on Tosquelles’ work and quickly found himself on the front lines of the struggle for Algerian independence, treating and housing FLN militants, before fleeing to Tunisia to avoid arrest. There, as a never fully trusted part of the FLN leadership, he became the Algerian liberation movement’s spokesperson to the West, while also acting as a sort of ambassador to much of sub-Saharan Africa, meeting a gallery of young revolutionaries whose approaches ranged from the nonviolent idealism of Congo’s Patrice Lumumba to the cynical tribal warlordism of CIA-sponsored Angolan gangster Holden Roberto.

Over the brief span of a life curtailed by leukemia at age 36, Fanon thus managed to engage directly and complicatedly with several of the 20th century’s crucial intellectual, cultural, and revolutionary movements: Négritude in poetry, existentialism and phenomenology in philosophy, psychoanalysis, and, of course, the movement with which his legacy is most closely identified, for better and for worse, decolonization.

Fueling Fanon’s relentless drive to be at the center of the action—mental and physical—was both a young man’s yearning for experiences of freedom and a young man’s intolerance of hypocrisy and insult. Before Claudia Rankine, Fanon was the poet of microaggression. And with Black Skin, White Masks (1952) he elevated it to a philosophy. Much of Fanon’s first book—birthed from a series of essays he wrote in his mid-20s—is a catalog of indignities and chronicle of humiliations, large and small, that he used to fuel his rage, which in turn fueled his talent and determination.

The catalyzing moment, or primal scene, in Shatz’s account, arrives while Fanon—then a medical student—is pointed at on a train by a white child, who says with either fear or wonder “Look maman, un négre.” Fanon reads the child’s outburst as atavistic fear, and so when the mother tries to mollify all parties by referring to “the handsome négre,” he famously responds, “The handsome négre says fuck you, madame.”

From this, Fanon developed the insight that a dark-skinned man who, in his words, “wants nothing more than to be a man,” finds himself everywhere subjugated by forces even more insidious and powerful than a racial caste system or organized discrimination—as was the case in the Jim Crow U.S. or apartheid South Africa. Mirroring Freud’s insight that hysterics suffered from their own memories, Fanon suggested that many people were in fact suffering from other people’s fantasies about them. Even in Fourth Republic France, a country where he nominally enjoyed equal status, a Black man remained subjected to a comprehensive and totalizing cultural imaginary that he could never escape, no matter how “educated” or “successful” or “white” he tried to become.

If a biography can be said to advance a thesis, Shatz wants to make the case that the angry young thinker who began with ‘Black Skin, White Masks’ and then progressed to a clarion call for therapeutic killing in ‘The Wretched of the Earth’ was activated equally by a desire for ‘a common humanity’ that was prevented from maturing by his early death.

Oppression by means of the other people’s assumptions and projections—an enlargement and direct politicization of Sartre’s existentialism—was to become Fanon’s initial major contribution to both Western and post-Western thought. He was among the first to take the measure of the psychic—and at times physical and socioeconomic—toll that came from living in a society where you were always an imaginary other. More than that, he provided these vague and inchoate feelings with a powerful theoretical and poetic language that anticipated and influenced the Black Panthers, Amiri Baraka, Edward Said and others.

It was a short step from Fanon’s innovations in the field of psychology to his sympathies with Algerian Arabs and Berbers, many of them his patients. Despite Algeria’s full political integration into the postwar French Republic, they were treated as second- or third-class citizens, strangers in their own land, their votes gerrymandered into irrelevance. And this was before the French adopted a program of rural “pacification” that displaced 2 million Algerians into concentration camps. The biography comes to life in these sections, chronicling Fanon’s adventures as a doctor attuned to the suffering around him, then as FLN sympathizer turned militant turned spokesperson and ambassador. Largely this is because Shatz gives space to the living voices of those who worked with Fanon, knew him intimately, and experienced his evolutions alongside him. The most powerful of these belongs to Marie-Jeanne Manuellan, Fanon’s amanuensis during the Tunisian years when he wrote the works that would give him his posthumous reputation as an advocate of the liberating power of unbridled decolonizing violence.

The interviews with Manuellan (who died in 2019 as Shatz was writing the book), along with testimonies from Fanon’s medical colleagues Jacques Azoulay, Charles Geromini, Alice Cherki—either from Shatz’s own interviews, independent written recollections, or archived recordings—add needed depth and complexity, as well as providing glimpses into the daily character, contradictions, and charisma of the man behind the public intellectual mask. Fanon left little in the way of introspective journals, notes, and letters—he was for much of his adult life a fugitive and part of a revolutionary movement given to bouts of paranoia and internal purges—so the biographer’s task becomes assembling a collage of impressions that also becomes a collective portrait of the men and women around Fanon.

Shatz also calls attention to what might be considered the constitutive and—for Shatz— redemptive paradox of Fanon’s life and his thought: Someone who asserted the powerful need to recover and assert an apparently authentic identity nevertheless, as a non-Muslim, non-Arab, Black man, devoted himself to a cause that was not “his own,” and one that he knew would always view him as an outsider. Shatz readily acknowledges that Fanon, had he lived, might not have been welcomed in a post-independence Algeria, established as an Arab, ethno-nationalist, quasi-religious state that granted citizenship only to Muslims, continued to discriminate against its indigenous Berber minority, and would later enter a decade of civil war.

If a biography can be said to advance a thesis, Shatz wants to make the case that the angry young thinker who began with Black Skin, White Masks and then progressed to a clarion call for therapeutic killing in The Wretched of the Earth was activated equally by a desire for “a common humanity” that was prevented from maturing by his early death. Because Fanon’s life was unfinished and fragmented, this claim can no more be refuted than the equally plausible suggestion that Fanon might have given up on intellectual life entirely and plunged into other decolonizing struggles in Africa, popping up in Angola, Mozambique, and Rhodesia like a Mr. Kurtz of African liberation.

The biography’s title, which refers to Fanon as a rebel rather than a “revolutionary,” also effectively shades the subject with a certain ambivalence. Rebel conjures a post-Second World War typology that includes both those with and without causes—James Dean, Camus, the Beats, Charlie Parker, Elvis. Fanon was bebop and spoken word poetry, he was hip. We learn that he secretly liked to dance—he smoked even when it got him in trouble with his pious Muslim comrades at the FLN.

Unlike the revolutionary, however, the rebel crucially remains locked into a relationship of opposition. In Shatz’s telling, Fanon needed that oppositional energy, whether it was criticizing the authenticity fetishism of Césaire’s négritude even as he borrowed from it, or Sartre’s colorblind Marxism, even when desperate to be recognized by him. “Tell Sartre to preface me,” was practically his dying wish. In this way, and others, he was also susceptible to the rebel’s need for approval, whether deferring to the authority of the intellectual doctor-fathers of dialectics, or helping the hardline FLN leadership orchestrate cover-ups of the purge and murder of one of Fanon’s closest Algerian comrades—Abane Ramadane—as well as FLN massacres of Algerian villages sympathetic to more moderate independence movements.

Shatz cites Simone de Beauvoir’s impressions of this contradictory personality: “a partisan of violence who was horrified by violence,” who, at the same time, nevertheless “blamed himself for weakness,” telling her that “everything he’d written against intellectuals, he’d written against himself.” These internal divisions and uncertainties, brought to the fore by the harsh reality of high stakes guerilla movement politics, ultimately make Fanon more compelling than the social media warriors and defacers of paintings and posters who today claim him as a model.

The contradictions, the qualities of a man working through a dance of self-hatred and self-love, are also what link him to his biographer. “Even a biography such as this contains a concealed memoir of sorts,” Shatz says in response to a question about antisemitism in a recent interview with BookForum. That memoiristic or autobiographical element, however, is often concealed from the author as much as the reader. As someone who has written an overt memoir, I couldn’t help wonder what kind of story Shatz is trying to tell about himself through Fanon. In answering the interviewer’s question about the influence of Jewish thinkers on Fanon as confessionally as he does, Shatz seems to be trying to create his own space for a discernible Jewish identity that is at odds with what he refers to as the Israeli state’s “instrumentalization of anti-Semitism and the memory of the Holocaust.”

What that identity looks like can be glimpsed at another revealing moment in The Rebel’s Clinic. In a final note on sources that serves as a coda, Shatz attributes the origin of his fascination with Fanon and the evolution of his political consciousness to copies of Black Skin, White Masks and The Wretched of the Earth that he comes across as a teenager, “in the small library of radical literature my father kept in our basement.” There they were, he tells us, “sandwiched between The Autobiography of Malcolm X and Isaac Deutscher’s The Non-Jewish Jew.” The bookshelf placement serves as a neat metonymy of Fanon’s political position: somewhere between the pure identity politics of Black nationalism and world socialism. But the bookshelf also provides a window to Shatz’s own sympathies, formed from his father’s library: pro-Black in the United States, anti-colonial internationally, and influenced by the “negative identitarianism” of one of the most self-punishing manifestations of Jewish history’s long messianic tradition.

Deutscher’s title essay is a paean to his Jewish heroes: Spinoza, Marx, Heine, Freud, Rosa Luxemburg, and Trotsky. What makes them heroic, according to Deutscher, is how they were able to transcend (or renounce, or “refute”) both their Judaism and even Jewishness in the name of a greater universal law. For Deutscher, the anointed biographer of Trotsky, full Jewish emancipation only arrives from the disavowal or dispersion of Jewish identity into universal, or at least global, revolutionary struggle against injustice everywhere. Having renounced both religion and nationhood, Deutscher retains Jewishness for himself at the cost of defining it as a special ethical category that excludes most ordinary Jews: “I am,” he declares, “a Jew by force of my unconditional solidarity with the persecuted and exterminated.” This rule of the underdog becomes then the whole of the law, and it offers an even narrower path to righteousness than the strict Orthodox upbringing Deutscher disowned.

Fanon, on the other hand, as much as Shatz would like to persuade readers of a potential universalist message latent in his political thought, came to understand that emancipation from the poisonous self-loathing that was a byproduct of European colonial and racial oppression could only come about through a stage of usually violent, often obnoxious (“Fuck you, madame!”), radical identity assertion.

And here The Rebel’s Clinic and its author end up reaffirming a curious double standard that has not only persisted but only become more deeply unexamined among those who keep alive certain Trotsky-ish and New Left attitudes toward oppressed peoples who tried to form post-1945 nation-states: Nationalism, strategic identity politics, and a muscular, militarist culture that glorifies or at least tolerates violence is accepted as a necessary precondition on the road to freedom for every oppressed group—except Jews. “The Jew,” somehow still singular, (often still imagined monolithically and monochromatically Ashkenazi and usually male) is instead “chosen” anew for the double task of emancipating himself first from some backward-looking relic of antiquity and the Middle Ages called “Judaism,” before moving on to help liberate both comrades and former enemies from capital H “History.”

As any reader of Fanon could tell you, the fact that this anti-identitarian fantasy of ethical (rather than ethnic) superiority was promulgated by Jews—some of whom had themselves experienced some of the worst antisemitic violence (Deutscher survived and witnessed two pogroms as a teenager and managed to avoid arrest in Moscow in the 1930s)—does not guarantee its authenticity, rather the opposite: Jewish (fore)skins, socialist masks.

For all Shatz’s admiration of Fanon as a rebel and résistant, alive both to large and small injustices meted out against him and against others, his views about what makes a good Jew remain weighted to the side of non-Jewish Jewish exceptionalism and self-sacrifice. Throughout the biography, Shatz consistently memorializes the Jewishness of certain figures in Fanon’s orbit while also placing that Jewishness under erasure. He refers to Henri Alleg, an Algerian newspaper editor arrested and tortured by the French army as “a communist intellectual of Jewish origin.” There is Daniel Timsit, “a young Jewish Communist,” an FLN bomb maker, along with Fanon’s medical comrades Azoulay and Cherki, also identified as “Algerian Jews,” all of whom gave themselves for the cause of Algerian independence. And then there those who aligned themselves with Fanon’s more radical decolonizing ambitions for the rest of Africa, like Elaine Klein, who might have been one of Fanon’s lovers, “an American-Jewish woman in her early thirties,” and the Congo-based State Department analyst Herbert Weiss, “who had fled from Austria with his Jewish family in 1938.” The Jewishness of these characters is not exactly relevant to the story Shatz is telling, or at least Shatz doesn’t say why it could or should be so. Mere signaling in this way, however, creates the biography’s own kind of “garden of the just” of internationalist non-Jewish Jews whose story becomes part of Fanon’s legacy, between the lines, and in which a similar-minded reader or author can perhaps recognize himself.

There were, however, Jewish Fanonians who did not see themselves only as “allies,” but understood their own struggles in a Fanonian idiom: Of these, none was more instrumental to Fanon’s posterity than Claude Lanzmann. Like Fanon, Lanzmann was a teenage résistant and continued to see himself as a consummate “existentialist” man of action: As Fanon would be later—notably in Sartre’s extravagant essay in praise of violence written as a preface to The Wretched of the Earth—Lanzmann was exoticized on account of his “authentic” suffering and resistance to it by the Sartre-de Beauvoir power couple with whom he remained fatefully entangled. He was both de Beauvoir’s lover—officially approved by Sartre—and an editor at Sartre’s magazine, Les Temps Modernes. It was Lanzmann who delivered the manuscript of what was to become The Wretched of the Earth to Sartre. He then arranged the publication of its infamous opening chapter, “On Violence,” in the magazine, and also choreographed the eventual meeting between a dying Fanon, Sartre, and de Beauvoir in Rome in August of 1961.

Shatz acknowledges that Lanzmann’s early documentary films on the IDF (Tsahal) and on the futile armed revolt at the extermination-work camp Sobibor “advanced a strikingly Fanonian defense of violence, arguing that Jews had remade themselves as a people only by taking up arms and fighting their oppressors.” Lanzmann’s kind of Jewish Fanonism is not, however, to Shatz’s taste (read his sneering appraisal of Lanzmann’s memoirs in the London Review of Books (“Nothing he hasn’t done, nowhere he hasn’t been,” March, 2012). In the biography, however, Shatz lets him off with a little litotes, concluding that “it is unlikely Fanon would have approved of Lanzmann’s passion for the world’s last settler-colonial state.” I, for one, wish they could have had that conversation.

“Settler-colonial” is of course a favored epithet of the contemporary internationalist and academic left that seeks to quarantine Jewish national aspirations from those of other newly created post-1945 nation-states. It’s unclear from his writings elsewhere on the subject whether Shatz himself believes the modern State of Israel to have “always already” been “settler-colonial” from the time Zionism existed only as an idea, or whether it became so definitively only after winning the 1967 war. Reputations and opportunities, not to mention paying jobs, in the world of left publishing and, increasingly, in the U.S. State Department rise and fall on such questions, or one’s ability to avoid being pinned down on them.

In his position as the U.S. editor and unofficial chief Israel correspondent at the London Review of Books—a publication with nothing nice to say about Israel—Shatz has tended to cultivate a sort of strategic ambiguity about ultimate causes and final solutions of the Zionist question while remaining firmly opposed to almost every action undertaken by an Israeli government in his lifetime. Nevertheless, writing in the magazine pages in the aftermath of Oct. 7 (“Vengeful Pathologies,” Oct. 19, 2023), before landing on the ideologically correct conclusion that Israeli intransigence was ultimately to blame for the world’s lack of sympathy for Jewish victims, he attempted to remind those in the LRB‘s not at all antisemitic milieu that “intergenerational trauma is as real among Jews as it is among Palestinians.” He even offered a light chastisement to the enthusiastic pro-Palestinian demonstrators in Western capitals: “The ethno-tribalist fantasies of the decolonial left, with their Fanon recitations and posters of paragliders, are indeed perverse.” What this perversion is, though, he doesn’t spell out, perhaps because to do so would force him toward ultimately unanswered and perhaps unanswerable questions about Fanon’s ethics of violence and the intersectional left’s renewed enthusiasm for them.

In The Rebel’s Clinic and on multiple occasions elsewhere, Shatz likes to make the argument that Fanon’s views about violence have been distorted and caricatured by both fans and haters on account of a mistranslation: “It is, of course, true that Fanon advocated armed struggle against colonialism,” he writes in the essay about Oct. 7, “but he referred to the use of violence by the colonised as ‘disintoxicating’, not ‘cleansing’, a widely circulated mistranslation.” In the BookForum interview he additionally clarifies this: “By taking up arms, the colonized overcome the almost drunken stupor in which they have lost themselves and in which they ceased to think of themselves as potential historical actors.” So not Al Aqsa Flood, then, more like Al Aqsa Purge. But this tangling over distinctions—when is a cleanse not “disintoxicating” and vice versa?—overlooks the ways that even “limited” violence metastasizes. People can and do become addicts of violence. “Trust us, we only want to kill enough of you to feel better about ourselves” is not a negotiating strategy.

Whatever it is, this kind of political expression certainly limits alternatives, and it has often led to a nihilistic politics of despair. This is indeed how Shatz understands what has happened to Israel: grown into an overdog, excessively powerful nation intoxicated by its own myth of “disintoxication” from Jewish weakness, yet still subjugated by what Shatz—in tune with the beliefs of many intellectuals of the cultural left—considers to be a “traumatic hallucination” of another Holocaust. Perhaps this Israel—to speak in the psycho-political idiom of The Wretched of the Earth—is what the end state of Fanonian self-realization really looks like: a country—like the man—in perpetual struggle with itself, with its own fantasies of weakness as well as with other people’s fantasies about it. To argue that, however, would take a much greater rebellious streak.

Marco Roth is Tablet’s Critic at Large.