Illuminating a New Megillah

A careful rethinking of a challenging Jewish narrative, for Purim

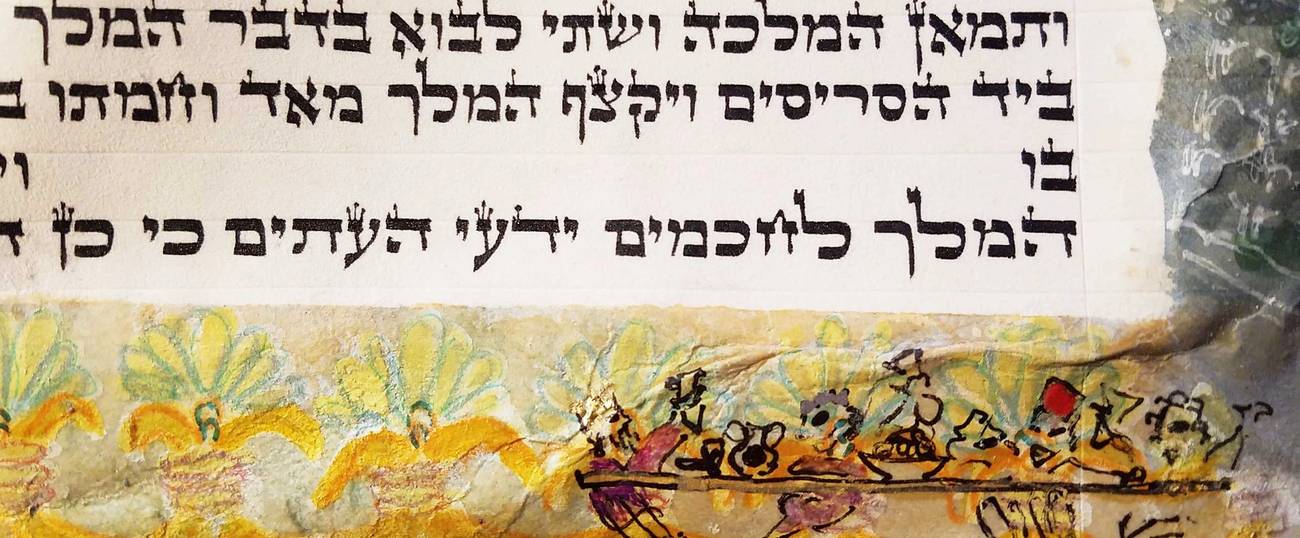

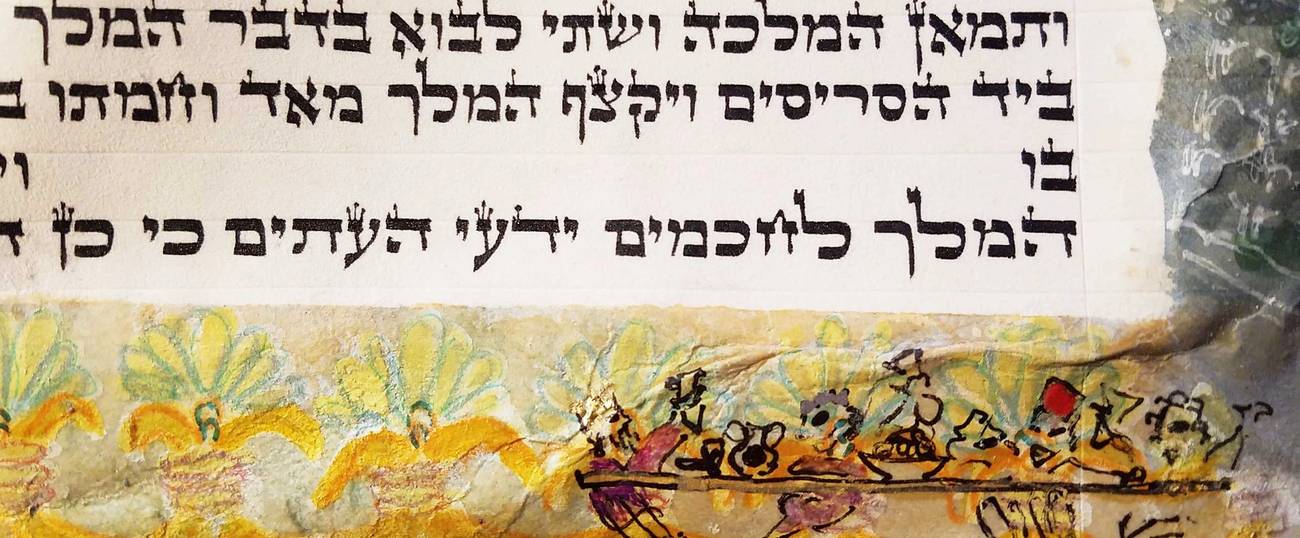

Above and below the rigid script, curtailed scenes play out in rectangular blocks of color. Horses with riders dressed in sky-blue robes are led down ancient streets; magnificent arches and temples jut up from the parchment; the delicate, fine-line figures of kings and advisers strut through polychrome space, their actions taking place against backgrounds filled with vivid colors and swirling patterns. The milky cast of the ink lends the images a certain freshness—though the art style in question, illumination, is an ancient one, the pictures feel spry and playful, almost as though they’ve been torn from a children’s book.

For the past year, Benjamin Marcus, an architect and freelance graphic designer and illustrator, has been working on an illuminated Megillah that tells the story of the Book of Esther, the central text of the festival of Purim. Though the finished product will serve mostly for personal use—Marcus’ brother commissioned the illuminations and provided the base scroll, written by a sofer on animal parchment—the project has seen Marcus tangling with the ritual proscriptions involved in making Megillot, while giving him an opportunity to reflect on his own long-standing concerns about the history and tradition of Jewish art.

“It’s an interesting ongoing question for me—when it comes to Jewish architecture, there isn’t really the same set of models or sense of legacy in the way there is for Christianity, which is based on Roman and Greek forms,” Marcus explained on a recent visit to his studio. In setting out to illustrate the Book of Esther, Marcus quickly realized that the pursuit of an appropriate, and appropriately Jewish, visual style would require heavy research, as well as a touch of flexibility and invention. Since the Megillot, as written artifacts, don’t begin to show up en masse until around the 17th century, Marcus began his studies there, perusing the illuminations of works like the Ferrara Megillat Esther, created in Italy in 1616.

Viewing the Met’s permanent collection of artworks from the sixth to fourth centuries BCE (the Book of Esther is set in ancient Persia) helped Marcus settle on patterns that would form the background of the Megillah’s panels. Drawing on ornamental motifs from sculpture and statuary helped to anchor the illustrations in a particular time and place, though Marcus was careful not to lean too heavily on this strategy. “I’m not trying to do a historical document, because I think that would betray the point of the story, which is a quasi parable,” he explained. “It’s not told the way other histories are told; it doesn’t feel like Torah. It’s repetitive, it’s filled with these bureaucratic details—it feels different.”

Coming to terms with the odd character of the text—unlike the other Megillot, God isn’t directly mentioned in the Book of Esther—had to happen before illustrations could be made, and Marcus was helped along when his brother gave him a commentary on the Book of Esther written by the 19th-century rabbi and Bible commentator Malbim. “He looks at the story essentially as a story of politics, and what was happening in this particular kingdom,” Marcus said. “In his reading, the story is really about the bureaucracy that existed, and the role it had in our near annihilation.” Taking careful notes while reading the commentary, Marcus began to work out what details would lend themselves to visual storytelling, though there was still plenty of work to be done before the first image was formed.

While the illuminating itself has taken a little more than a hundred hours to complete, Marcus has been preparing for nearly a year, a process that’s taken him down several rabbit holes. He had to tutor himself in the practice of painting with egg tempera; before applying his final designs to the Megillah, he needed to practice on a spare sheet of kosher klaf parchment, which wasn’t easy to find. He managed to track down a sofer living in Brooklyn, but ran into trouble communicating with him. “Even though he’s living in the 21st century in Brooklyn, he doesn’t speak any English,” Marcus said. “Getting there and then negotiating Williamsburg to find this guy in a basement—if he hadn’t someone visiting him who spoke English, I wouldn’t have been able to speak with him.”

Interlocutors have their own part to play in the Book of Esther, whose plot tends to progress by the device of pages and couriers, a phenomenon that shows up in Marcus’ illustrations. “There’s all this mentioning of the king speaking to his eunuchs, or the messenger, or the people who are reading him his records, and then those characters turning around and telling another person,” Marcus said. “So depicting that became very convenient, especially with the narrow 2-inch margins I was working with.”

The apocalyptic overtones of the plot, and the overwhelming presence of extended feasts in the story, find their way into the general color scheme of the illuminations. “I started off illustrating the panels with neutral colors, and then it slowly gets darker and darker as you go along, until it gets to the point where Haman is about to complete his plan of annihilating the Jews,” Marcus explained. Once Haman’s treachery is exposed, however, the color scheme gradually lightens, rising from the depressive, bruise-like tones of the story’s darkest moments to light blues and blends of orange and yellow that seem redolent of sunsets.

Though Marcus hasn’t finished illustrating the scroll yet, he wants the final images and their backgrounds to reflect the exuberance of Purim, and what he sees as the story’s central motif, that of abundant feasting. “I want the end of the scroll to be majorly festive,” he said. That means brighter colors, and a loosening of the geometric patterns in the panels’ backgrounds, an unfurling that suggests the Jewish people’s release from the reticulations of the Book of Esther’s rambling plot.

All in all, Marcus’ Megillah mounts a careful rethinking of a challenging narrative. In the process, it devises a unique visual style capable—after passing through the treacheries of bureaucracy and ritual rigors of Megillah-making—of expressing the sudden rush of freedom, and the boundlessness of a safety suddenly bestowed.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Bailey Trela is a writer living in Brooklyn. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Full Stop, Harvard Review, and The Threepenny Review.

Bailey Trela is a writer living in Brooklyn. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Full Stop, Harvard Review, and The Threepenny Review.