Putting the Jew Back in the Queer

Lillian Faderman’s new biography of Harvey Milk re-centers much of his activism on lessons he learned from his Jewishness

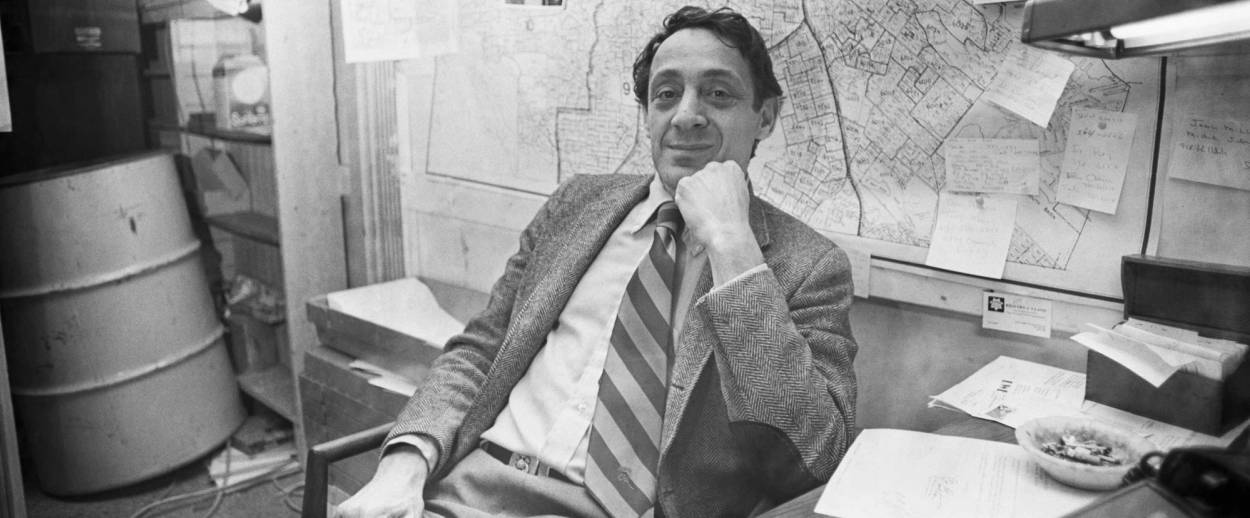

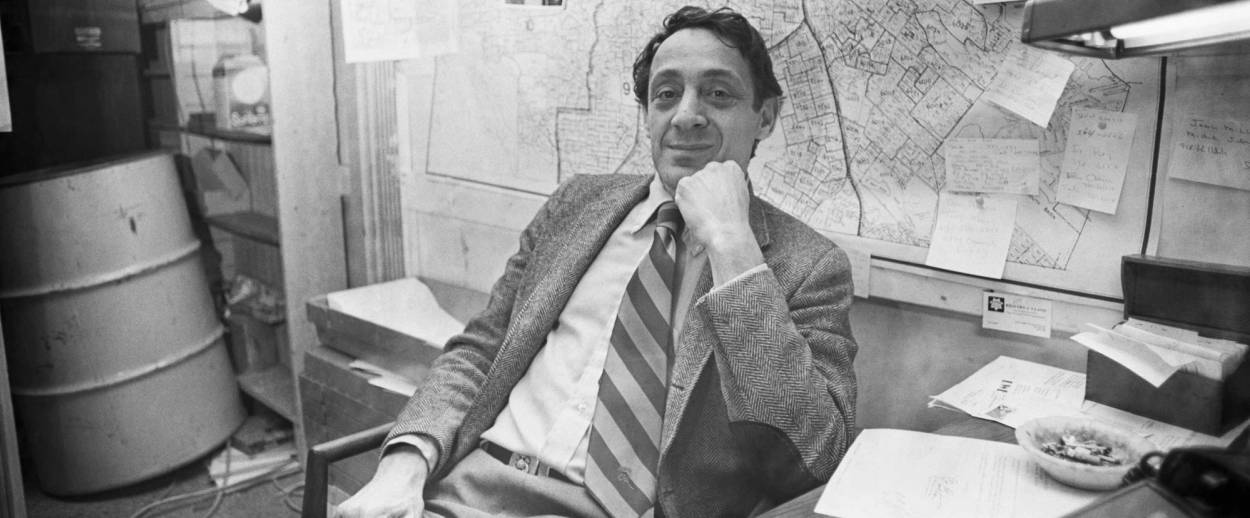

Harvey Milk, whose dramatic political career was cut tragically short by an assassin’s bullets, was born on May 22, 1930. Lillian Faderman’s new biography Harvey Milk: His Lives and Death(a volume in Yale’s Jewish Lives series) is not a hagiography but nonetheless celebrates the complex gay man who didn’t get to see his 50th birthday, let alone his 88th. This elegantly written and well-researched book recovers the Jewishness that has too often been erased or glossed over in the mythologizing of a gay icon.

Faderman’s narrative of Milk’s life does justice to the biographical landmarks included in Randy Shilts’ 1982 The Mayor of Castro Street, a seminal source for the two Oscar-winning films about Milk, Rob Epstein’s 1984 documentary, The Times of Harvey Milk, and the 2008 Gus Van Sant biopic, Milk. Faderman covers Milk’s time in the navy, his stint as a white-collar worker in the insurance industry and on Wall Street, his transformation from a Goldwater Republican to a hippie who resisted the Vietnam War and sought fame but experienced failure in the New York theater world before moving to San Francisco and starting his famous Castro Camera store, the catalyst for which was the ruining of a roll of film that included pictures of Milk and his lover, Scott Smith.

Milk wanted to serve the gay community and promote pride rather than shame; his camera business was also the start of his lifelong emphasis on the importance of gay economic and political power. Castro Camera quickly became a gay community center, and then campaign headquarters for Milk’s political career.

Although we now think of Milk as the beloved San Francisco supervisor who was martyred by a bigot, Faderman reminds us that it took him three tries to earn that legislative position, with a failed campaign for State Assembly thrown into the mix. Milk’s “loud” theatrical out-style, and his refusal to let more “sympathetic” allies serve as the spokespeople for the queer community, often caused him to be at odds with San Francisco’s Democratic political machine, including its gay powerbrokers.

In keeping with prior biographical treatments of Milk, Faderman provides a great deal of detail on Harvey’s tragically short time as supervisor, including and especially his work defeating Proposition 6 (also known as the Briggs Initiative), which would have made it illegal for gays or anyone who had anything good to say about homosexuality to be employees of the California public schools. She also details Milk’s tense political relationship with Dan White, the former supervisor who killed him and San Francisco Mayor George Moscone.

In sharp contrast to earlier biographical accounts, however, she provides ample space to Milk’s Jewishness, in life and also in his death. We learn that Walter Caplan, who hosted a yarmulke-wearing Harvey at Passover seders in his home, instructed those who were preparing his body to lie in state at City Hall to secure a plain wooden coffin. At the memorial service held outside of City Hall on Nov. 29, 1978, Rabbi Alvin Fine, a civil rights activist and retired head of Temple Emanu-El, San Francisco’s main Reform congregation, delivered the eulogy. After the City Hall service, an explicitly Jewish service was held at Temple Emanu-El, with Allen Bennett, at that time the city’s only out gay rabbi, delivering the eulogy. (The less than gay-friendly senior rabbi of the congregation had to be pressured into accepting Bennett at the bima.)

But the Jewish picture that Faderman paints of Milk is hardly confined to his death, and distinguishes her Harvey Milk from de-Jewed gay icon depicted by Shilts, Epstein, and Van Sant. “I think they saw his Jewishness as incidental to who he was,” Faderman told me, in an email interview. “I see it as central to who he was—and I believe he did too.”

Although Epstein does deserve credit for depicting an often coded, “kosher style” Milk, it is Faderman who provides explicit and ample evidence for Harvey’s Jewish pride informing and intersecting with his vision for gay pride. In “A Nice Jewish Boy,” Part I of the book, Faderman provides family history, which includes an observant grandfather who helped to found the first congregation in Woodmere, New York, in which Milk later became a bar mitzvah. She also chronicles the anti-Semitism that plagued his Long Island boyhood, including a Jewish music teacher denied employment by the Woodmere school board. The Holocaust in general, and the resistance fighters of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in particular, which he learned about as an adolescent, greatly impacted his political rhetoric, whether he was fighting against police brutality or against Proposition 6.

During his adolescence, Milk sought out a rabbi as he struggled with what was then the secret of his homosexuality and never forgot the sage words he was offered: “You shouldn’t be concerned about how you live your life, as long as you feel you’re living it right.” In college, he became a member of a Jewish fraternity and participated in events sponsored by Hillel and the Intercollegiate Zionist Federation of America. And when he came home from college one winter break, he helped a friend hang Christmas lights by constructing a Star of David with his allotment of bulbs.

Milk’s Jewish visibility became a model for and intermingled with his gay visibility. In his early days in San Francisco, he toyed with the idea of opening a Jewish deli. When he decided on Castro Camera instead, he hung his bar mitzvah picture on the walls of what would become an iconic gay institution. When Scott Smith reluctantly agreed to run his first supervisor campaign, Harvey gave his non-Jewish boyfriend a gold chai, which Smith wore. Even in his first flawed and failed campaign, he strove to articulate what would eventually become his winning coalitional vision: “I will strive to bring the government to the people, be they blacks or fellow Jews, be they the tax-starved elderly or fellow small-shop owners.”

As an activist scholar, Faderman works to, in her words, “bring to light material that had been suppressed or considered unimportant because it didn’t support the reigning narrative.” In Harvey Milk: His Life and Death, she is able to restore Milk’s hitherto suppressed or trivialized Jewishness through careful archival research as well as original interviews with those who knew and worked with him. And as one of the foremothers of lesbian studies as well as the author of the relatively recent The Gay Revolution (2015), she also excavates the role that Anne Kronenberg, who managed his successful supervisor campaign and became his assistant once he made it to City Hall, played as his feminist mentor and liaison to the lesbian community. It was thanks to Kronenberg that he learned to refer to the community as gay and lesbian, he learned to talk knowledgeably about the Equal Rights Amendment, and he learned to include women in general and lesbians in particular in the “us’s” he was determined to galvanize into a voting bloc.

Given Faderman’s convincing case for the central role that Jewishness played in Harvey’s life and death, I wish that she had considered Harvey’s legacy for queer Jews specifically. Many liberal Jews today are questioning whether and how intersectionality and coalition politics apply to them, as last summer’s Chicago Dyke March amply demonstrated. But this desire for more is ultimately a testament to the power of Faderman’s Jewish angle of vision on Harvey Milk’s life and its continuing relevance for Jews and non-Jews alike.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Helene Meyers, professor of English at Southwestern University, is the author of Identity Papers: Contemporary Narratives of American Jewishness. She blogs for Lilith Magazine.