Groupies

Eavesdropping on a book-club meeting and lamenting the unloved life of a writer

I was sitting in the upstairs lounge of a small local tavern when a dozen women of various ages strode purposefully through the doorway and quickly commandeered three tables. After pushing the tables together, they called for the waiter, and, as he brought over a pile of leather-bound menus, the women made their way to the coffee bar at the far end of the lounge.

I was seated at a table in the back, and had been for some time, getting nowhere on the whatever-the-hell it was I was struggling uselessly to write for some goddamn reason. I watched over the top of my laptop as one of the people from the group, a young woman who looked in her early 20s with close-cropped yellow hair and the practiced sincerity of a funeral director or a liberal arts post-grad, was shaking hands and exchanging warm smiles with each woman in turn. She carried a small black-and-red paperback in her hand—I tried to catch a glimpse of the title, but she clutched it, Holy Bible-style, to her chest. Then I noticed, with a shiver of horror, that the others were all holding their own copies of the same black-and-red volume.

Oh Dear God, I thought. It’s a fucking book club.

Every member, whether or not she had a shoulder bag, chose to carry her paperback tucked under her arm or clutched to her chest, like dead animals strapped to the roof of a brave hunter’s car.

With their free hands, they carried their coffees and took their seats around the table. Because I’m a glutton for self-punishment, I hit the mute button on my computer. The waiter took their dinner order—the No. 11 with chicken was a popular choice—and the young woman with the cropped yellow hair leaned forward and welcomed them.

“Some of you I know,” she said, which the women somehow found hilarious, “and some of you we’re just meeting.”

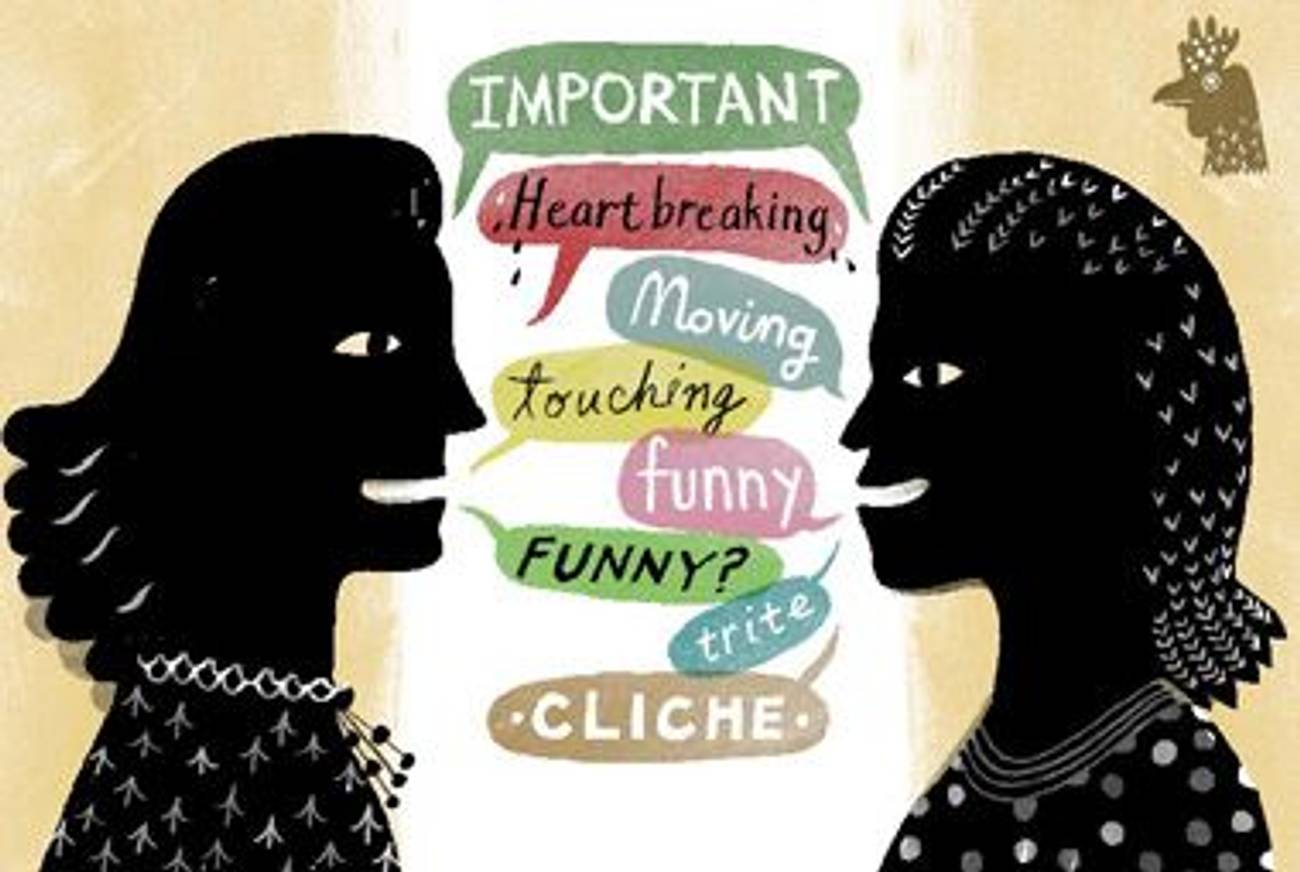

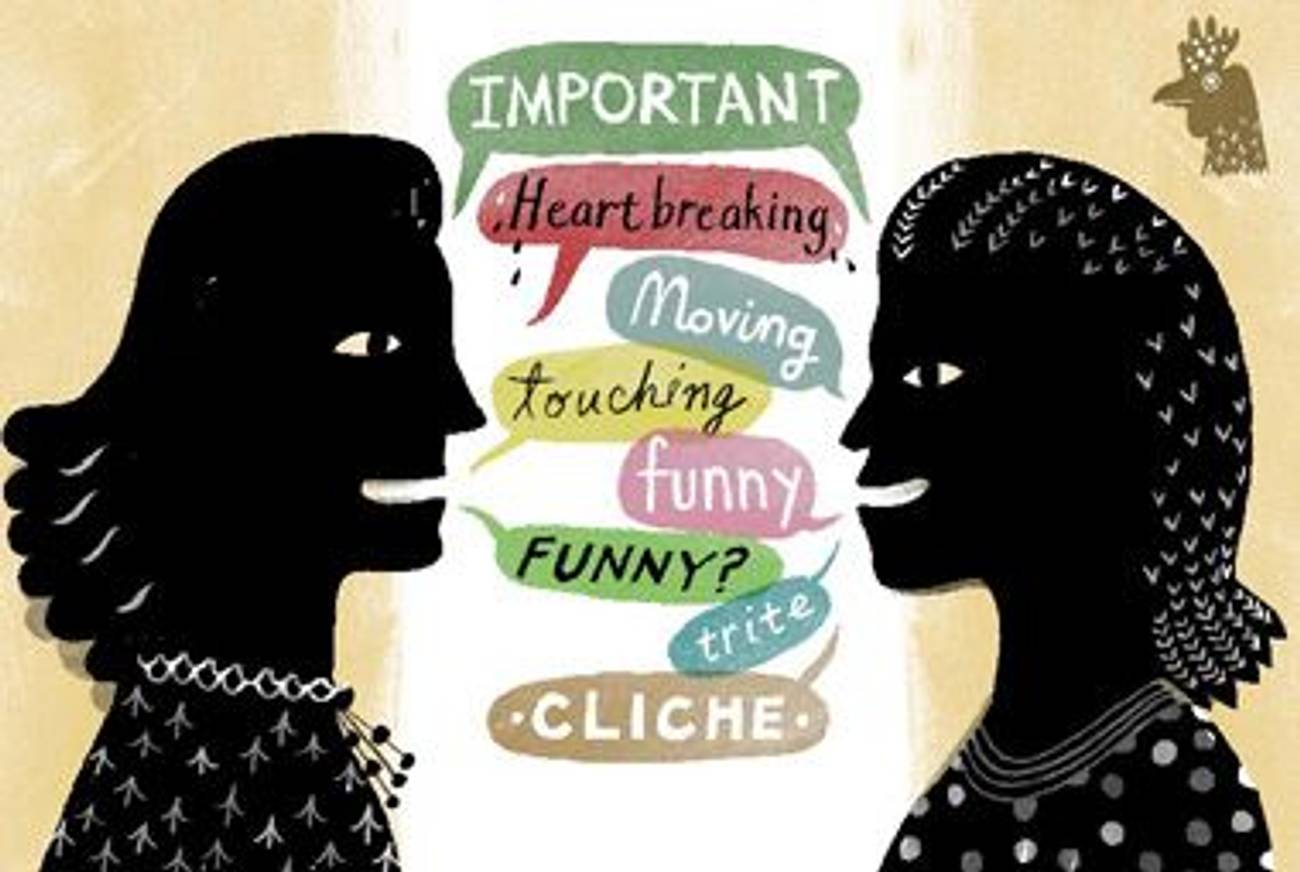

Yellow Hair went on to explain that if she seemed tired (she didn’t), it was because she had been up all night for three nights reading this wonderful book, which she adored. She really felt she had really like, you know, connected to the main character. It was such a complex, intricate story that she felt it would be a good idea to go around the table and have everyone say the one word they thought perfectly summarized it. She started the ball rolling by sitting back in her seat, folding her arms across her chest, and asserting, “Heartbreaking.”

Everyone nodded solemnly. “Mmm-hmm,” they said.

I should admit that this was a particularly bad time for me to run into a book trial such as this, having recently been the strung-up victim of one myself. The group that tried and condemned my writing, though, wasn’t made up of strangers. They were friends. I had had the temerity to write about a close friend of ours who was dying. Within the piece I examined the death of my beloved grandfather, the wasting away of my Alzheimer’s-ridden grandmother, the tragic death of a brother I never met, and anticipated my own rage that would surely follow my friend’s death. Our mutual friends declared it “opportunistic” of me to write about her. It was, they said, “in poor taste” and “wrong.” Perhaps I would have fared better with a jury of strangers.

“Gabby?” asked Yellow Hair to the woman sitting beside her.

“Moving,” said Gabby.

Everyone nodded. “Mmm-hmm,” they said.

“Very,” said Yellow Hair. “Sandra?”

“Touching,” said Sandra.

They all nodded solemnly. “Mmm-hmm,” they said.

“Danielle?” said Yellow Hair.

“Important,” said Danielle.

They all nodded solemnly.

“Important’s good,” said Yellow Hair. “Mara?”

“Funny,” said Mara.

A heavy silence fell over the court. The F word.

“Funny?” asked Yellow Hair. “I didn’t see it as funny.”

“Not funny,” explained Mara. “Comical. Comedic.”

People are funny, too, and by “funny,” I mean horrifying and detestable. Go visit our relatives at the zoo; there’s always that one monkey sitting calmly by himself, picking his feet, or gazing peacefully into the sky. Then the other monkeys come over, and everyone goes, well, apeshit.

“What are these?” my son asks, pointing up at the crazed monkeys.

“Your grandparents,” I say.

Yellow Hair shrugged and looked to the others. The others shrugged.

“But moving,” added Mara quickly. “Funny in a moving way.”

“Definitely moving,” said Yellow Hair. “I thought it was very moving.”

“Me, too,” said Mara. “Very.” Still feeling she hadn’t fully clawed her way back into respectability, she added: “Much more moving than the film.”

“Oh, definitely,” said Yellow Hair.

The ship of unanimity sailed on. Joyce went with “engaging,” Cheryl declared the book “brave,” and Nora proclaimed it “refreshing and absorbing,” which is actually three words, but since they were words everyone agreed with, her violation of the rules was overlooked.

I began to wonder just what this heartbreaking, moving, touching, important, funny in a moving way, refreshing, absorbing book was, when Yellow Hair called on Sally, a heavy, older woman at the far end of the table.

“Trite,” said Sally.

Uh-oh.

“Really,” she continued. “Just a big cliche.”

Sally didn’t like the book’s heavy female protagonist. She’d seen it before, heard it before; Sally wanted to know why all heavy protagonists are so pure and good, and if they are, why did it matter that they are heavy.

“I just saw it coming,” said Sally. “A mile away.”

“I can see that,” said Sandra.

Yellow Hair turned to look at her.

“You said it was touching,” Yellow Hair said.

“It was,” said Sandra. “But it wasn’t surprising.”

“No,” said Mara. “It definitely wasn’t surprising. That’s why I said funny.”

Only moments before, the black-and-red paperback looked like it was going to survive; now, the tide began to turn. Some of the group took Sally’s point of view, some took Yellow Hair’s; some tried to bring the group back into agreement by reminding everyone at the table how much better the book was than the movie, but those who disliked the book seemed to prefer the movie, and a woman at the far end of the table admitted she hadn’t even read the book, and had only seen the movie. Yellow Hair wasn’t giving up.

“I guess,” she said, “different people react to different things differently.” But this book, she insisted, was something special, particularly the heavy main character, who was so real and human that it was hard for Yellow Hair to not feel what she felt, to see the world through her eyes, and to internalize all the complex—

“No. 11 with chicken?” called the waiter.

He had returned with a large tray loaded with plates, cups, and bowls.

“Over here,” said Yellow Hair.

“I had a No.11 with chicken, too,” said Sandra.

“We all did,” said Danielle. Everyone laughed.

I was at a literary festival recently, and members of the audience were interested in writing. I told them to read Kafka’s “A Hunger Artist” first. Franz probably meant it to be about family, or existence in general, but it’s a pretty dead-on description of the writing life: You sit in a cage, starve to death, and nobody cares because they’re all off watching Avatar.

If you’re looking for love, don’t write. Odds are you’ll be hated. The best odds are that you’ll simply be ignored.

“Everything good here?” the waiter asked.

I noticed that the black-and-red paperbacks had been put away.

“Great,” said Yellow Hair.

Everyone nodded enthusiastically. “Mmm-hmm,” they said.

If you’re looking for love, don’t be a writer. Be a No. 11 with chicken.

Shalom Auslander is the author of Foreskin’s Lament, Hope: A Tragedy, and most recently Mother for Dinner. His new memoir, Feh, will be published this July. He writes The Fetal Position on Substack, so make that seven Nazis.