On December 2nd, 1980, Romain Gary lay down in his Paris apartment, a synagogue-size menorah at the foot of the bed, and put a .38 caliber Smith and Wesson in his mouth. Seconds later, the life of one of France’s most celebrated and prolific novelists—a decorated war hero, globe-trotting diplomat, and notorious lothario—was over. But this was more than suicide: It was the final act of mythmaking from a man preoccupied, above all, with manipulating the people and events in his life almost as deftly as those in his books.

“Immortal,” remarks Jeannot, the dictionary-obsessed narrator of King Solomon (1979) and one of Gary’s final alter egos. “There’s a word that always gives me pleasure.” The same sentiment is expressed more darkly in the autobiographical Promise at Dawn (1960): “The real tragedy is that there is no devil to buy your soul.”

Faustian collaboration being unavailable, Gary did the next best thing: He orchestrated the end of his life and its aftermath, leaving behind a note and instructions for the publication of The Life and Death of Émile Ajar, a confession of authorial subterfuge that revealed that the fêted young author Émile Ajar, recipient of the 1975 Prix Goncourt, was in fact Romain Gary, an out-of-vogue writer who had won the same illustrious prize 19 years earlier. With one bullet, French literature had lost two greats.

Self-invention means blurring the facts; it is only thanks to Gary’s biographer (and former lover), novelist Myriam Anissimov, that the details of his origins have been confirmed. He was born Roman Kacew in May 1914, in Vilna, Lithuania. His parents, Nina and Lebja Kacew, were Russian Jews, which contradicts Gary’s various stories about being of Tartar or Cossack descent on his father’s side, or the love-child of actor Ivan Mosjoukine. In reality, Lebja walked out on Roman and his mother, a former actress, when the boy was ten. Without a husband, Nina—immortalized in the memoir Promise at Dawn, Gary’s embellished masterpiece about their relationship—invested all her energy into shaping her son’s destiny. Call her the showbiz mother from hell: Her own career cut short, she was determined that fame would be visited on her son.

Nina suffered, Gary said in a 1973 radio interview, from “galloping Francophilia, a Joan-of-Arcism typical of Eastern European Jews.” Accordingly, when he was 14, the two of them moved from Warsaw to Nice so that Nina could realize her dreams for her Romouchka: “You’ll be a great French writer, you’ll be Victor Hugo, Chateaubriand, Gabriele d’Annunzio, ambassador of France.” They rented two rooms on the auspiciously named Avenue Shakespeare, and Roman, already fluent in Russian, Polish, and Yiddish, immediately learned French. Nina toiled, as Gary relates in Promise at Dawn, as a palm reader, hairdresser, dog groomer, lampshade maker, building manager, investor in a taxi service, and even as a scam artist, taking a turn in hotel lobbies as a Russian aristocrat forced to sell “the last of my family jewels.” Roman, meanwhile, went to school and, in his spare time, focused on renaming himself:

I sat day after day in my little room, waiting for inspiration to visit me, trying to invent a pseudonym that would express, in a combination of noble and striking sounds, our dream of artistic achievement, a pen name grand enough to compensate for my own feeling of insecurity and helplessness at the idea of everything my mother expected from me.

The process took time. In 1935 he changed his first name to Romain and finally settled on the full “Romain Gary” in 1940, while he was serving with the Free French Air Force in London. The surname was laden with significance, as he emphasized in a book-length interview with his friend François Bondy, La Nuit Sera Calme (The Night Will Be Calm, 1974): “Gari in Russian means ‘burn!’… I want to test myself, a trial by fire, so that my I is burned off.”

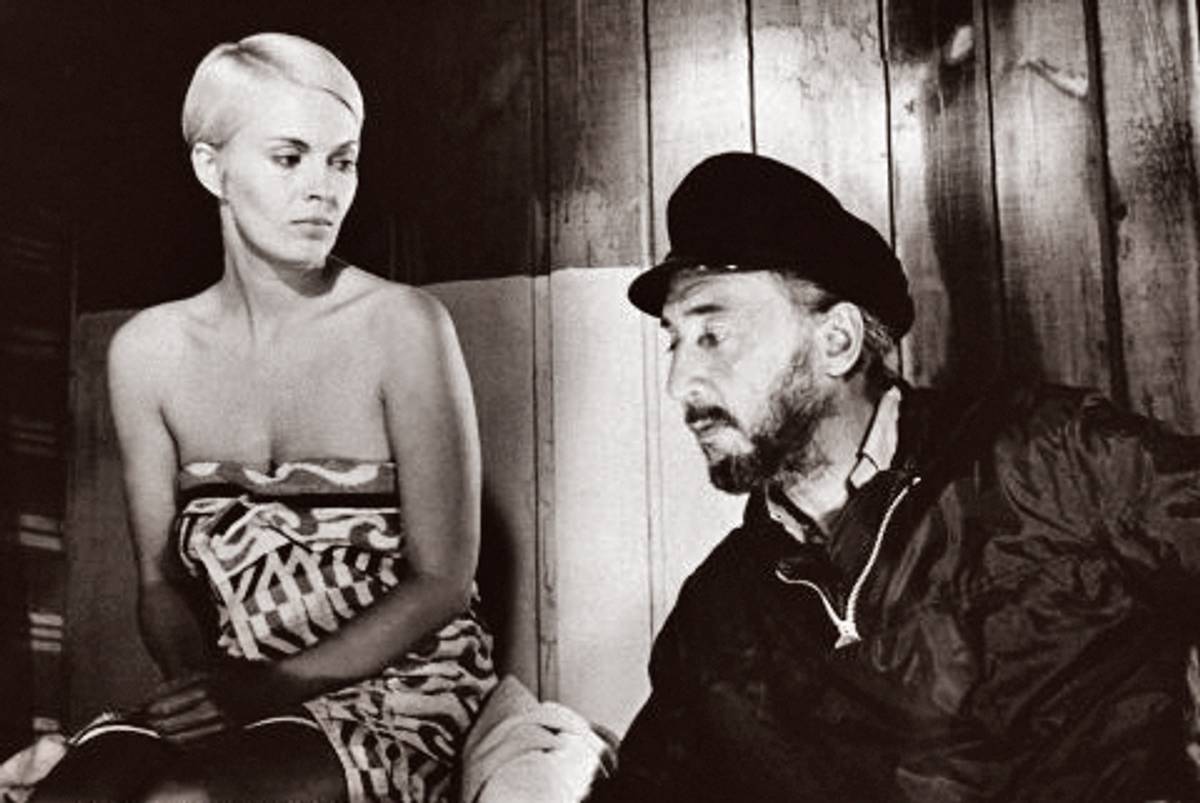

Nina was “pretty good at fabricating legends,” Gary reminisced in the 1973 radio interview, and for her son, she augured triumph in matters romantic (“The most beautiful women will be dying at your feet!”), military, diplomatic, and, above all, literary. One after another, her predictions bore out. In addition to numerous affairs, he was married twice (to author Lesley Blanch and the glamorous actress Jean Seberg), was awarded the Croix de Guerre, the Croix de la Libération and the Légion d’Honneur, served as a diplomat in Bulgaria, Paris, Switzerland, and the United States, and, of course, became one of the more famous writers of his day in a country where the literati were venerated on the order of movie stars. According to Blanch, she and Gary were on every party’s guest list: “We both loved it. And we knew everybody. Aldous and Maria Huxley, Igor Stravinksky and his wife Vera…James Mason, Sophia Loren, David Selznick.” Later, Gary and Seberg were close friends with William Styron, and regulars at the storied New York and Paris soirees hosted by author James Jones and his wife Gloria.

Gary had the talent to back up his high profile. Jean-Paul Sartre, in Le Temps Modernes, declared Gary’s first novel, A European Education (1945), the best written on the Resistance. Taking up what would become his perennial theme—man’s potential for brutality—it centers upon a Polish boy, orphaned by the Germans, who joins a group of Polish Resistance soldiers struggling for survival in the forests outside Vilna. It became a bestseller and won the Prix de Critiques, an honor Nina did not live to see. She had died almost three years earlier at age 59, but remained the animating force behind all her son’s decisions. He called her his “inner witness” and recounted thusly an episode when an Israeli journalist asked if he was circumcised: “It was the first time the press took an interest in my penis, and on live radio too. Of course I could not deny it, it would have been like spitting on my mother’s grave.”

During the first 20 years of Gary’s literary career, his Jewish identity was a subject of constant speculation. World War II was a recurring backdrop in his novels, and many of his characters were Jewish, but overtly Jewish themes were not often in the foreground (with the early exception of his unsuccessful second novel Tulipe in 1946, about a Buchenwald survivor in New York). Then, in 1966, Gary and Seberg visited the memorial of the Warsaw ghetto, in the city where he’d lived as a child for several years before moving to France. This confrontation with the trauma of history—a horror he narrowly avoided—was overwhelming. Gary hallucinated the arm of a hidden Jew emerging from a sewer grill shaking its fist, and fainted from the shock. When he came to, some combination of survivor’s guilt and righteous anger was conceived, taking shape in The Dance of Genghis Cohn (1967)—a breathtakingly original, hilarious, and complex exploration of Gary as a man, an author, and a Jew.

Genghis (né Moishe) Cohn, a comedian from Berlin imprisoned in Auschwitz, exposes his bare bottom to Schatz, the SS officer who kills him, and instructs him to “Kush mire in tokkes.” (Opines Cohn’s ghost: “There have undoubtedly been more worthy and noble last words in history than ‘Kiss my ass,’ but I have never made any claim to greatness and, besides, I’m quite pleased with my effort…”).

At the moment Cohn dies, his dybbuk invades Schatz’s subconscious, taking up permanent residence, teaching the Nazi Yiddish and introducing him to the joys of kosher cuisine: “When you share another person’s life, it’s only normal that the other party acquires some of your own habits and tastes. If Schatz wishes to eat kosher, that’s strictly his business. He even cooks himself some of our traditional little dishes, on Friday night, cholent, gefilte fish, tsimis.”

Eventually, a “writer” enters the narrative, in a twist that might be employed today by the likes of Charlie Kaufman. While it seems Cohn has been occupying Schatz’s imagination, the two are, in actuality, figments of the author’s imagination: “A writer’s subconscious is one of the filthiest places there are: as a matter of fact, you can find the whole world there.” The device is most explicit in a scene in which Gary depicts what happened as he fainted at the Warsaw Memorial.

In the novel, when he opens his eyes he starts swearing in Polish and overhears Seberg telling curious passersby that he used to live in the area. “Ah, we didn’t know your husband was Jewish,” exclaims one of them. “Nor did he,” she quips. (Gary’s English and American publishers found this postmodern twist problematic; the scene does not appear in the book’s translated version).

While the English translation won raves—”as close as anyone has yet come to sorting out the symbiotic Gentile-Jewish relationship,” said Marian Engel in The New York Times—and was eventually adapted into a film, it did poorly in France. Its Yiddishisms and gallows humor went unappreciated by Gallic critics, whom Gary accused, in a 1968 Nouvelles littéraires interview, of not understanding the book’s Ashkenazic perspective.

Gary had experienced this split reaction before. His third novel, Le Grand Vestiaire (The Company of Men, 1950)—narrated by a Resistance orphan who arrives in postwar Paris as a young boy and is taken under the wing of a Nazi collaborator—sank in France, yet became a bestseller in the United States. By the time of Genghis Cohn, Gary had decided that French critics considered him unfashionable, a conservative establishment figure with his Air Force and diplomatic background or, as he put it in The Life and Death of Émile Ajar, he had been “classified, catalogued, taken for granted.” Still, he took the novel’s cool reception in France to heart, advising Anissimov to avoid the Holocaust as a subject for her fiction. “He told me that when he wrote about Jewish subjects, his books were always failures,” she reported. “Once in the street, he turned to me and said dramatically, ‘les Goys don’t understand us. Don’t throw away your career.’”

If the Goys misunderstood Gary, so did the Jews. He was incensed to receive a letter denying him a listing in Who’s Who in World Jewry, the guardians of which, he retorted, were “pickier than Rosenberg and Himmler.” This was despite his own previous ambiguity on the subject. According to Nancy Huston, the author of an experimental biography of Gary in which she inserts herself as a character, when asked if he was Jewish, Gary would reply, “If people want me to be, I don’t mind.”

Too famous for his work to be judged without bias, Gary felt he needed to break free from categorization. So, in 1973, at age 59—the same age his mother was when she died—Gary invented Émile Ajar. He was by then twice divorced, retired from the diplomatic corps, and had published 22 books, including the Goncourt-winning The Roots of Heaven (1956), about illegal elephant poaching in Africa. It was time for a new adventure, as he explains in The Life and Death of Émile Ajar: “I was tired of being nothing but myself…there was the nostalgia for one’s youth, for one’s debut, for one’s renewal…. I was profoundly affected by the oldest protean temptation of man: that of multiplicity.”

While still publishing as Romain Gary, he launched a second career as Émile Ajar (Ajar: a play on the Russian word for heat) in a complex ruse, a precursor to the likes of JT Leroy. Publishers were told that Ajar was a 34-year-old Algerian former medical student, responsible for the death of a young Parisian on whom he had performed a botched abortion. To escape jail, he fled to Brazil, from whence his manuscripts were sent. (Gary had a friend in Rio who assisted in this regard.) Gary’s cousin’s son, Paul Pavlowitch (who later wrote a fictional biography of Tom Ripley, the murderous trickster made famous by Patricia Highsmith), was enlisted to pose as the author on the phone, in photographs, and, on rare occasion, in person.

Ajar’s debut, Gros-Câlin (Cuddles, 1974), is a tragicomic tale of a loveless office clerk’s relationship with his pet python, the titular Gros-Câlin. Just as Genghis Cohn anticipates postmodernism with its self-reflexiveness, Gros-Câlin contains commentary on the scam of which it is a part. A python sheds its skin and, one character points out, “We all have identity problems. Sometimes you have to recycle yourself elsewhere.” The python “resembles an elephant’s trunk”—a sly allusion to The Roots of Heaven.

Greeted as the work of an utterly fresh voice, Gros-Câlin garnered raves and became a bestseller, but it was soon overshadowed by Ajar’s follow-up, The Life Before Us (1975), which sold millions, was translated into 22 languages, and became the author’s most beloved novel, adapted for the Oscar-winning Madame Rosa (1977), starring Simone Signoret.

The Life Before Us is narrated by Mohammed—”but everyone calls me Momo, because it sounds littler”—a 14-year-old Arab orphan who lives in the deprived Paris district of Belleville with Madame Rosa, an ailing 68-year-old, 220-pound Auschwitz survivor and ex-prostitute who looks after the children of her former colleagues. “Madame Rosa,” says Momo, “was Jewish when she was born in Poland, but she’d peddled her ass for several years in Morocco and Algeria and spoke Arabic as well as you or me. She knew Yiddish too for the same reasons and we often spoke that language together.” Though Gary would claim in The Life and Death of Émile Ajar that Momo was based on Diego, his son with Seberg, the orphan’s relationship with Rosa recalls that of Gary and Nina in Promise at Dawn; Momo is 14, the same age Gary was when he first arrived in France.

While critics saw Romain Gary as a has-been, they were smitten with Momo and his ostensible creator. A critic for the newspaper Le Canard Enchaine, who had condemned Gary as “creatively impotent,” declared The Life Before Us “the best love story of the season” and its author a “pure talent.” The breathless delight with which Ajar’s novels were received suggests that Gary had been right—reviewers were weary of him. While recent appraisals have recognized the trauma of the Holocaust as the emotional core of The Life Before Us, at the time French critics paid scant attention to the novel’s Jewish element, seeing it instead as authentically Arab. In the deepest of ironies, some readers even characterized the novel as anti-Semitic. Claude Michel Cluny wrote in Magazine littéraire, that “under the good of government of Vichy, people would have been falling over themselves to give [The Life Before Us] an award.”

Ajar’s runaway success elicited scrutiny. Some observers suspected he was an established writer using an alias and even asserted that he might be Gary. Publisher Lynda Noël reported seeing the Gros-Câlin manuscript in Gary’s apartment, while Laure Boulay of Paris-Match identified similar phrasing and ideas in the two authors’ works. Gary responded coyly to Boulay: “No one has realized the extent to which Ajar is influenced by me. In the example you so justly quote, it would even be possible to talk of out-and-out plagiarism.” But Ajar admirers brushed off these accusations: A Nouvelle Revue Française contributor insisted that “Gary is a writer who has come to the end of the line. It’s unthinkable.”

Then events turned downright farcical. The Life Before Us was awarded the 1975 Prix Goncourt, the rules of which stipulate that it may be awarded to an author just once in his lifetime, and Gary had already received it for The Roots of Heaven. He instructed Ajar’s lawyer to turn down the honor on her client’s behalf, but the prize administrators would hear nothing of it. “The Goncourt Prize cannot be accepted or refused any more than life and death. Mr. Ajar remains the laureate.”

Five years later, of course, Gary decided to “refuse” life. Despondent over Seberg’s sordid death (her naked body was found in the back of a car; the death was eventually ruled a suicide) and disillusioned with the literary world—jealous, even, of Ajar’s success—Gary took matters into his own hands, having told a friend that “if my mother were here, this would not be taking place.” He wished his closing words to be “I have finally expressed myself,” but the last line of The Life and Death of Émile Ajar is what resonates: “I’ve had a lot of fun. Thank you, and goodbye.”

Emma Garman has written about books and culture for Newsweek, The Daily Beast, Salon, Paris Review Daily, Words Without Borders, Longreads, and many other publications. Her Twitter feed is @emmagarman.

Emma Garman has written about books and culture for Newsweek, The Daily Beast, Salon, Paris Review Daily, Words Without Borders, Longreads, and many other publications. Her Twitter feed is @emmagarman.