The French Riots and the Jews

The recent chaos is not an antisemitic intifada—it’s something worse

Abdulmonam Eassa/ Getty Images

Abdulmonam Eassa/ Getty Images

Abdulmonam Eassa/ Getty Images

On June 30, three days after the killing of Nahel Merzouk, 17, by a police officer during a police check in the city of Nanterre, near Paris, and the ensuing riots all across the country, right-wing representative Meyer Habib, a French Israeli citizen and close associate of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, published an article on Facebook titled “INTIFADA SCENES IN FRANCE,” from which I quote:

Since the last three days France is burning in its lost territories of the Republic and way beyond!

Burned French flags, burned city halls, burned police stations, burned stores, cars and schools! (…)

The Memorial of deportation in Nanterre vandalized! Antisemitic and anti-white tags blooming! Some call for the Sharia and vengeance!

In those territories, hatred of France, hatred of whites, hatred of Jews, have been thriving for years, most often in all impunity!

Nothing justifies such chaos! Not even the tragic, abnormal passing of a 17 years old young man, who had tried to escape police several times.

When Sarah Halimi was slaughtered for 20 minutes in front of 20 policemen by an Islamist who is almost free today, nobody ransacked anything!

Every political leader worthy of the name should call to a return to calm and to the respect of the rule of law!

Sarah Halimi was a 65-year-old retired school teacher. On April, 4, 2017, she was beaten to death at home and thrown out of her window by Kobili Traoré, a 27-year-old Muslim drug addict who had broken into her home and later claimed to have been possessed by demons.

Two days after Habib’s post, on July 2, at the start of Sunday’s cabinet meeting, Netanyahu himself made a statement about the riots in France. The Israeli government, he said, saw “with utmost concern the displays and waves of antisemitism sweeping over France” and the “criminal assaults against Jewish targets. We strongly condemn these attacks and we support the French government in its fight against antisemitism,” he added.

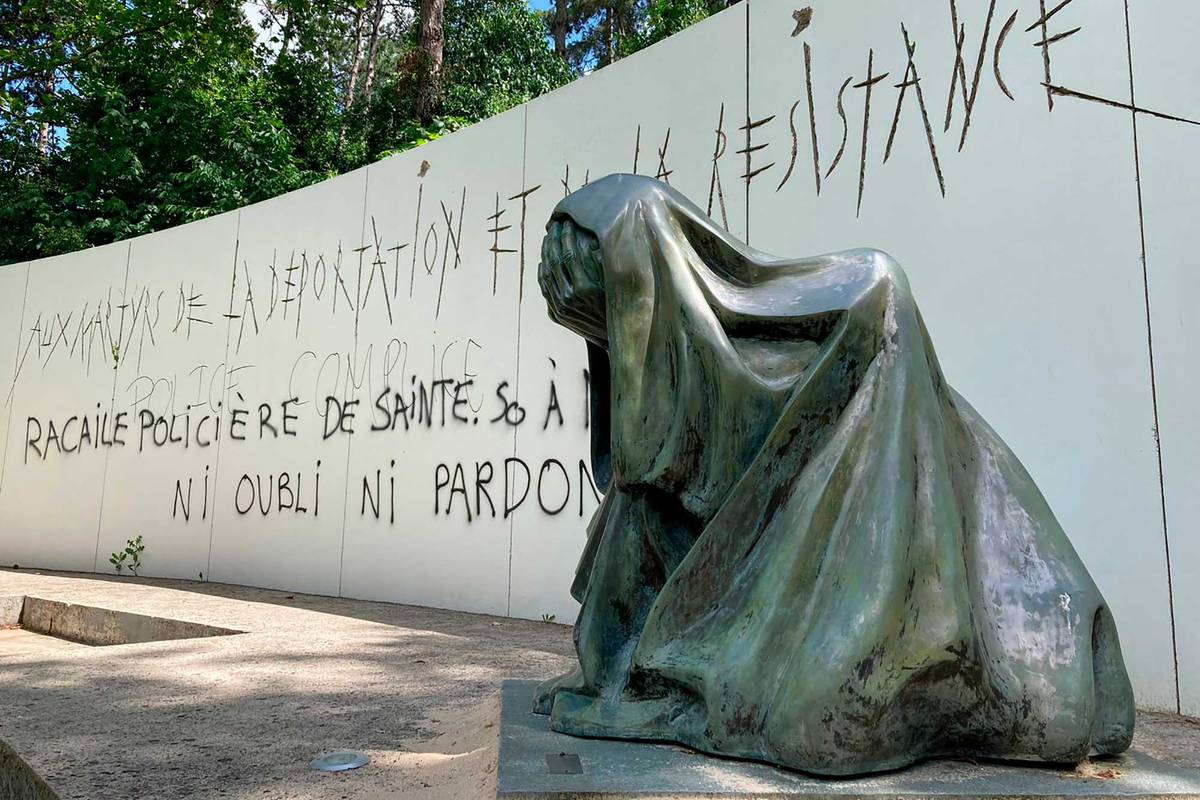

Netanyahu’s statement was published the same day by the Jerusalem Post, along with Habib’s statement. As an example of the antisemitic attacks that both men had mentioned, an accompanying article quoted “the Holocaust memorial” of Nanterre, whose French flag had been destroyed, and on whose wall anti-cop tags had been discovered. On July 7, under the title “The riots in France have become antisemitic,” the J-Post published another piece, an op-ed by a German writer named Thomas Stern, who used the same memorial incident as the sole example to support his thesis. The next day, it was the turn of the English Telegraph to use the same picture of the same Nanterre memorial for an article titled “France’s Jewish community on high alert after nationwide riots.”

There is a reason why everyone is using the Nanterre memorial as evidence of the riots’ antisemitism: There is no other even vaguely plausible example. In fact, even the case of Nanterre is deceiving. First of all, the Nanterre wall is neither “a Holocaust memorial” nor a “memorial of deportation” but a monument dedicated to “The martyrs of deportation and of the Resistance.” It was commissioned in the mid ’90s by the former Minister of Interior Charles Pasqua, who had been a high-ranking Resistance fighter of the Gaullist movement.

After the war, Gaullists believed that the unity of the French after the war was of the utmost importance. In order to maintain it, he denied for decades the specificity of the history of the Jews and their suffering during the years of occupation. France’s postwar Gaullist governments heavily censored the first books and films on the fate of the Jews and the role played by the French police in the deportations. The accepted version of the war was that all French citizens had experienced the same suffering and oppression. As in the USSR after WWII, Jews were invisible and their experience of the Vichy regime untold. Pasqua, an old-fashioned Gaullist with ties to the far-right, shared that version of history and commissioned the Nanterre monument accordingly.

AP Photo/Cara Anna

If the Nanterre memorial symbolizes anything, then, it is the ambiguity of French memory regarding WWII until the end of the 1990s, when French President Jacques Chirac finally officially admitted the Vichy government’s responsibility for the fate of the Jews of France. It is not a tribute to the Jews and was never conceived as such. To read anti-cop graffiti inscribed on its wall as proof of a “wave” of antisemitism is therefore to misunderstand both France’s tortuous relationship to its own past and today’s antisemitism.

Were kosher restaurants and Jewish stores ransacked during the riots? Of course they were—but no more than nonkosher restaurants and stores that happened to be within reach of the rioters and looters. In fact, from a Jewish standpoint, if anything is remarkable, it is the almost complete lack of specificity in the choice of the businesses targeted. According to all available reports, it appears that only one business was specifically destroyed for what it was—the Happy Café, a gay-friendly bar in the city of Brest, whose owner had to close down during the riots after reading messages on Telegram calling to “burn the fags, let them die in hell by the Koran,” followed by the name of the establishment.

The example of the Happy Café shows how easy it would have been to call to attack synagogues, Jewish cultural centers, and so forth. And yet, this was not done. The vast majority of the stores ransacked or destroyed were either chosen at random or because of the alleged luxury brand they represented (in city centers, Nike or Louis Vuitton were targets of choice). Given France’s heavy record of antisemitism since the 2000s, and the unprecedented intensity of the five days and nights of rioting across the country, the real news was that Jewish businesses, synagogues, and residences were not targeted as such.

“After the J-Post article was published, we had to set up a video conference with the Jewish Agency and the Ministry of Aliyah in Israel to set the record straight,” said Yonathan Arfi, the new, young, left-wing president of the CRIF, the (secular) institution representing the Jews of France. “We realized that Israelis were watching the riots with glasses dating from 2014—when antisemitic attacks in France rose up to 800 per year—while we were looking at these events through the lens of 2005—the year the banlieues exploded out of anger and social frustration after two teenagers were killed running from the police.”

2014 marked both the peak of random antisemitic incidents across the country and the prelude to the deadly terror wave that began on Jan. 7-9, 2015, with the killings at Charlie Hebdo and the Hypercacher kosher supermarket in Paris. Throughout the spring of 2015, the French authorities counted nearly one attempted violent attack per week, culminating in the Bataclan massacre on Nov. 13. The tension began to fall only after the mass killing the following year in Nice, where a heavy truck attacked the crowd watching the fireworks display on Bastille Day, July 14, killing 86 people and injuring hundreds more.

Most of these attacks contained at least one antisemitic element—Charlie Hebdo was perceived as Zionist-controlled, the Hypercacher of course was Jewish, and the Bataclan had been on the target list of Islamist groups for years for being owned by two Jewish brothers, a fact that authorities and the media denied, but that French Jews understood only too well, especially after the decade they had been through. As a result, the number of aliyahs from France, on a constant rise since the attack on the Ozar Ha Torah school in Toulouse in 2012, reached 8,000 in 2016—an astonishing number.

Today, according to the CRIF, the number of French Jews making aliyah has fallen back to 1,500 per year, though antisemitic aggression remains frequent. There were 436 antisemitic attacks in 2022, a level reached in the early 2000s and which has never fallen since. While Jews represent less than 1% of the French population, they are the targets of 61% of anti-religious acts against persons. These numbers, provided by the Ministry of Interior, probably underestimate the level of antisemitic aggression, since verbal attacks and insults on social media are not included.

So if right-wing pessimist Meyer Habib is wrong, is left-wing optimist Yonathan Arfi right? Should we really look at today’s situation through the lens of 2005—that is to say, through an anti-racist lens, as he claims to do, and as most of the Anglo-Saxon media covering the riots have done?

It is helpful to look back to what actually happened in 2005. On Oct. 27, 2005, in the city of Clichy-sous-Bois, two kids, Zyed Benna, 17, and Bouna Traoré, 15, were electrocuted inside a substation while trying to escape the police. It is widely assumed on the left—i.e., in most of the media—that these deaths started the riots that inflamed the cités (the French equivalent of the American “projects”) that surround most of the urban centers in France and that are mainly populated today with migrant families.

According to a less popular opinion, however, it was a tear gas grenade shot three days later by a police unit targeting a group of rioters in Clichy-sous-Bois that accidentally hit a nearby mosque full of Ramadan worshippers that fueled the three weeks of riots that ensued, during which five people died (three by asphyxiation caused by fires, two beaten to death). In other words, the anger that triggered the 2005 events may have been religious as well as social. This theory is held by, among others, Gilles Kepel, a leading scholar of Islamist movements in France.

The truth may lie somewhere in between. According to their families, and contrary to what police reports later claimed, Traoré and Benna were not fleeing the police because they were about to commit a burglary but because they had no ID cards on them and feared that they would be arrested and miss Ramadan dinner. That was back in 2005, a time when “social workers could still enter the cités and manage to convince parents to bring their children back home,” as a former high school teacher named Ugo Portier told me.

Portier has spent the last 40 years in Bobigny, a city near Paris that is home to some of the worst cités in the country. He campaigned for the radical left party LFI (La France Insoumise) until 2019, when he realized how wrong LFI—and the left in general—was about the situation of disenfranchised Muslim youth in France.

“If you look at what happened this time, he added, you see that the riots took place in two stages,” he told me. “First, let’s mark our territories by burning everything that represents the French state and French authorities in our neighborhood: police stations, city halls, public services of all kinds including schools and public libraries (35 of which were burned down during the riots). Second, let’s attack all their downtown businesses. In other words, a secessionist strategy. This is one of the reasons why the police mostly focused on the very young, occasional looters downtown. The pressure was such that the police forces simply could not get into the cités during these five days.”

Seen in this light, the rioters who vandalized the Nanterre wall in the hours that followed the “white march” for Nahel Merzouk the first day of the riots appear to have been looking for French symbols—not Jewish ones. They did not go after a monument, they went after the French flag, which they took down.

It is also clear that attacks on French symbols go along with attacks on Jewish symbols and Jews, at least by implication. In Sarcelles, near Paris, for instance, according to the city’s former Mayor Francis Puponni, “when the rioters decided to go after the French luxury stores outside of their own neighborhood, the first stores they stormed were all Jewish-owned. Why? Because to them France means riches and because Jews are supposed to have money.” In other words, these stores were attacked because they were Jewish and because being Jewish means being French—being integrated.

At the heart of the present situation, then, is not just a “police problem” or a “laïcité” problem, or even an employment problem, but a crisis in what the French call “assimilation”: the process through which specific groups and communities leave much of their particularism behind in exchange for equality and political and social rights that will make them indistinguishable from the rest of the population in the public sphere. And it is a crisis that affects all sides.

Because the Jews were the first group to serve as guinea pigs for assimilation after their emancipation during the French Revolution, because they were for long its sole beneficiaries—and because assimilation is now seen by everyone from the undergraduate-level readers of Franz Fanon to the nonreaders of the cités as a scam played on poor, dark-skinned peoples by the racist colonial system—Jews are now considered to be, at best, voluntary victims of said system, or at worst its collaborators and profiteers.

In that regard, it is therefore tempting to see the random, spontaneous, antisemitic attacks that plagued France between 2000 and 2014 and beyond—that is to say before and after the terror wave—as a non- or pre-verbal designation of the enemy: the energetic condition, so to speak, for the subsequent terror to fall on everyone. Contrary to what Meyer Habib wrote, what was really scary in the antisemitic murder of Sarah Halimi is not that her killer was an Islamist—it’s that he was not.

So has more than 20 years of rabid, often Islamist-inspired antisemitism in France exhausted itself? Or is it so ingrained now that the new generation can do without the explicit reference to the Jews in its war against assimilation? Either way, what no one wants to grasp is the complete failure of the assimilationist model, which has been abandoned not only by the kids of the cités but also by the society at large.

There is a long and a short story for this lack of faith. The long story, of course, is the Vichy regime. During WWII, contrary to what the right claims today, not only did the most assimilated Jews not escape persecution, but the Consistoire—the religious Jewish structure of the era—supported the collaboration, a position that has been rightly regarded as a perverse outcome of the assimilating process. As Yonathan Arfi phrases it: “if the assimilation process had succeeded, the CRIF (a secular organization born out of the Jewish Resistance) would not exist. There would be only the Consistoire. The CRIF is the result of a failure, which is why, as an institution, we are incomprehensible and why we attract antisemitism.”

But the assimilation did not only fail the Jews. It failed postwar migrants from North Africa, too. Aside from racism, one of the most underestimated reasons for why the French failed to develop any active policy to integrate migrants from their former colonies was that this would have been seen as a casus belli by the new nationalist Algerian and Moroccan regimes, whose oil and gas were vital to the French economy. In 1993, King Hassan II from Morocco could still state on French public television that “Moroccans would never be French, did not want to assimilate, and France would be well advised not to try.” The Algerian FLN was even more nationalist. Honor was at stake.

The former colonies made a point of directly controlling their nationals on French territory, a deal to which the French state assented. As a result, the ex-colonies also controlled the mosques and migrant culture in France.

Caught between French prejudice on the one hand and the control exercised by their countries of origin on the other hand, migrants were actively prevented by both their old and new state authorities from developing their own autonomous culture inside France. This conflict of loyalties often plagued the migrants themselves, especially the fathers who in the Algerian case had fought the French during the war of independence. It is the failure of the second generation of migrants, and of the French government as well, to solve the contradictions of identity produced by this bifurcated reality during the French civil rights movements of the ’80s that led to the building of the walls enclosing the cités, to the rise of Islamist propaganda, to the riots of 2005, and to today’s crypto-secessionism.

The researcher Hugo Micheron, whose last book, Les Démocraties face au jihadisme européen, will be published in English soon, explains that today, social groups instrumentalize each and every incident to denounce Islamophobia. “Very serious matters like the killing of Nahel Merzouk are being put on the same level as superficial ones to trigger a feeling of permanent threat, paranoia, and emergency,” he explains. “They call this ‘micro-aggression,’ but in fact, this narrative produces a ready-made interpretative grid where Muslims and descendants of Muslims are natural permanent victims of the system. What is really scary is that far-right groups in France have started to mimic that strategy. They, too, exploit what they call anti-French ‘micro-aggressions’ in order to nurture ‘the Great Replacement theory.’ Both of these narratives are martyr-producing machines.”

How to resurrect an assimilation model that works in such a context is anybody’s guess. One thing is certain: Denouncing a nonexistent French Muslim intifada against French Jews won’t help. The problem here is much worse.

Marc Weitzmann is the author of 12 books, including, most recently, Hate: The Rising Tide of Anti-Semitism in France (and What It Means for Us). He is a regular contributor to Le Monde and Le Point and hosts Signes des Temps, a weekly public radio show on France Culture.