Disorderly Conduct

The writer and critic Bernard Lazare, Dreyfus’ earliest defender, wed Zionism and anarchism to become one of France’s most famous polemicists and a political clairvoyant

Since the late 18th century, young French men from the provinces have “climbed” to Paris to make their fortune and name. Lazare Bernard, the son of a Jewish family from the southern city of Nîmes, made the climb for quite the opposite reason: to reject his family’s fortune and name. Soon after he arrived in Paris’ Gare de Lyon in 1886, the 21-year-old switched his first and last names and plunged into socialist and anarchist politics.

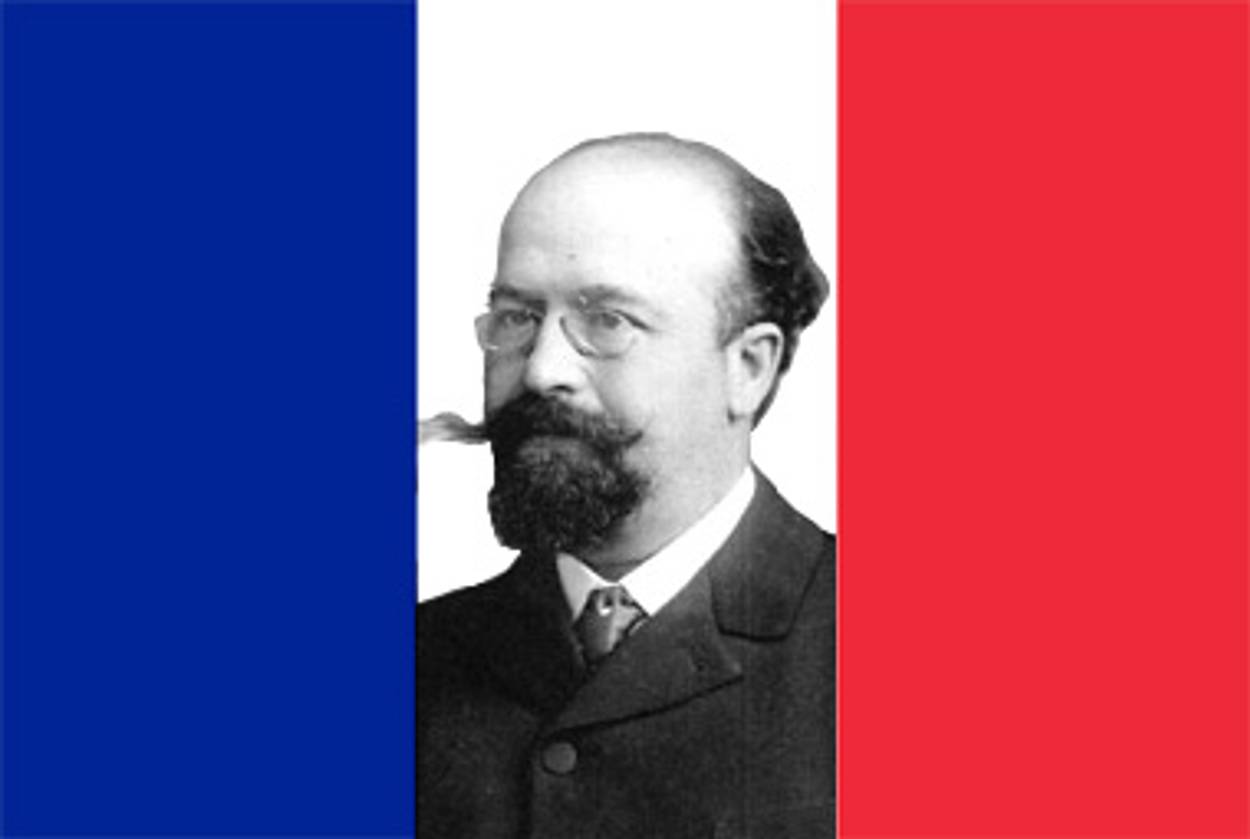

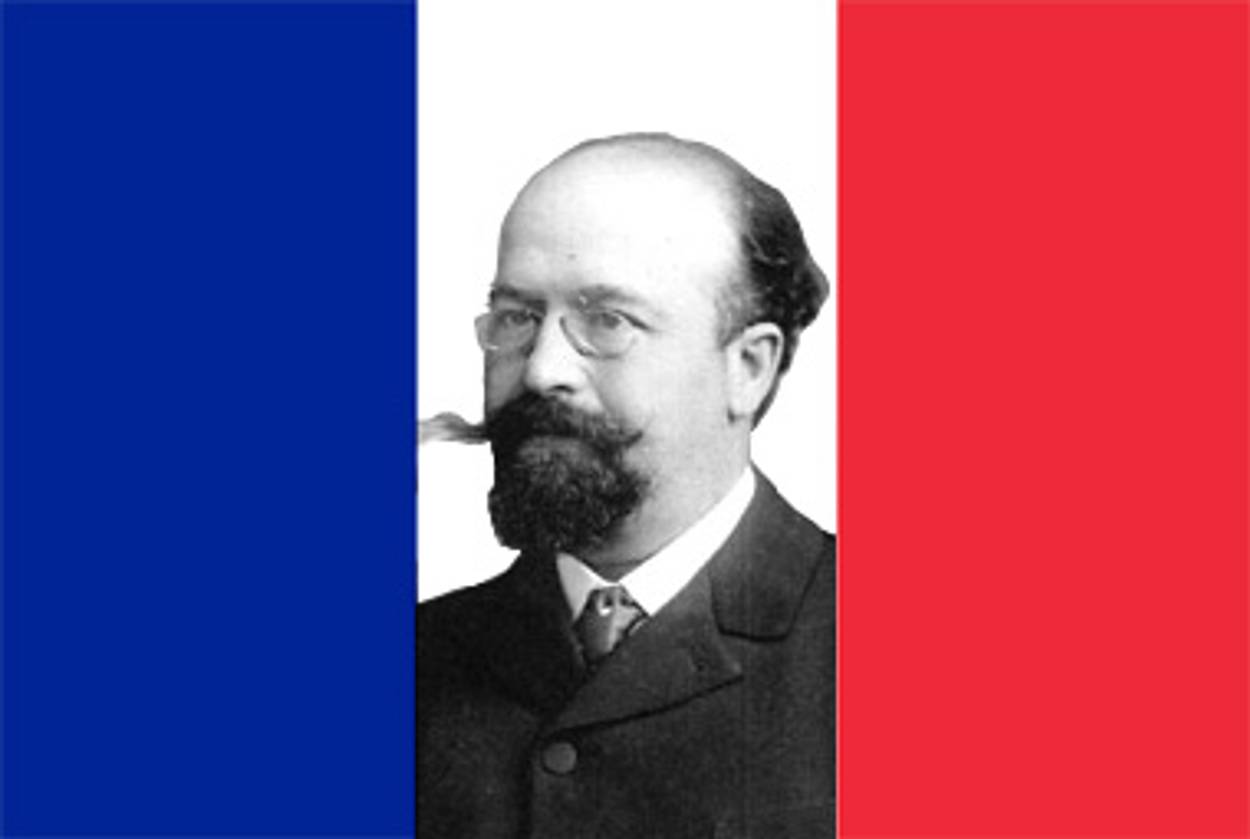

Yet Bernard Lazare never rejected fame. Over the next decade, he became one of Paris’ most respected and feared journalists and literary critics, his dapper suits and delicate pince-nez belying a fierce and combative character. Yet that fame failed to endure: Though he was the first of Alfred Dreyfus’ defenders and the first of French Zionists—roles deeply entwined with one another—Lazare is mostly forgotten today. Lazare, however, deserves a second look; his life story reveals the aspirations and the limitations of French Jewry at the dawn of the 20th century.

For tourists, Nîmes is best known for the bullfights still held in its Roman arena. For the French, Nîmes is notable for its large Protestant population—as anomalous in this overwhelmingly Catholic country as Belfast is in Ireland. In the 19th century, Nîmes was the capital of France’s thriving textile industry and the birthplace of the famous rugged fabric, denim, that took its name from the town. The shmata trade, however, was the affair not just of the local Protestants but of Jewish families as well. Significantly, this small but influential community—home to the Crémieux clan, whose most notable member, Adolphe Crémieux, served as minister of justice in the Second and Third Republics—had not just stepped off the boat: Many of the Jewish families in Nîmes had roots that extended at least as far back as the Avignon Papacy in the 14th century, while yet others were as ancient as the Greco-Roman ruins littering the countryside.

While Lazare’s maternal line seems to have stretched back several centuries on French soil, it was his father’s family, immigrants from Germany, that had entered the textile trade and rose to prominence. Like many young men from families of means, young Lazare rebelled against the middle-class traditions and tepid faith of his parents. At the local lycée, he announced to one and all his hatred of authority and power, be it his father, his teachers, or the republican state. “I have always held in horror masters and rulers of any sort,” he wrote as an adult. It was his life’s credo.

But Lazare was hardly a rebel without a cause. At first, he plunged into symbolism, a literary movement that anticipated our own Age of Aquarius. Led by the poet Stéphane Mallarmé, the symbolists turned their backs not only on the stodgy pieties of bourgeois France but on rationalism itself. Like the surrealists who would shortly follow, they insisted on the reality of unconscious and irrational forces at work in the world and our selves.

But the purity of art couldn’t contain an active mind like Lazare’s. In the hothouse atmosphere of fin-de-siècle Paris, his aesthetic concerns quickly blossomed into political engagement: He was as eager to challenge traditional political parties as he was traditional artistic schools. And he certainly had ample opportunity to do so: In the last decades of the 19th century, Paris was rehearsing our own era of the Internet, convulsed by the explosive growth of the penny press that left the city awash with cheap, mass-circulation newspapers that made sport of the reputations of politicians and powerbrokers. Lazare flourished in the bedlam of Parisian journalism; by 1892, he was writing for several different papers as a theater and book critic.

Two events propelled Lazare away from the arts and toward politics: anarchist terrorism and the Dreyfus Affair. For Lazare, these seemingly disparate phenomena had a great deal in common.

For most of us, anarchy invokes visions of a Montessori playground or the lawless regions of Sudan. In Lazare’s Paris, it meant a wave of terrorist attacks that paralyzed the city with fear. Between 1892 and 1894, politically motivated bombers hit targets ranging from the National Assembly to popular cafés, a wave of terror climaxing with the assassination of the French President Sadi Carnot. These so-called acts of “propaganda by the deed” aimed at nothing less than the collapse of the Third Republic—for the anarchists, the rights guaranteed by the state amounted to little more, in the famous phrase of Anatole France, than the right to starve while living under a bridge.

But these deeds had nothing in common with Lazare’s brand of anarchism. He was as appalled by the bloody terrorist acts as he was by the repressive laws passed in their wake. For Lazare, workers would inevitably get the short end of the stick whether they lived under a socialist or a conservative regime. Governments may change, he believed, but the exploitation and neglect of the poor and the disenfranchised remained constant. Only a society of workers’ cooperatives, he believed, democratic and decentralized, could meet the material and emotional needs of all citizens. If a Tea Partier was to marry a Communist, their ideological brainchild might resemble Lazare.

In 1894, however, the arc of Lazare’s career was suddenly hauled into the powerful gravitational pull of the Dreyfus Affair. Long before renowned writers and politicians like Emile Zola, Jean Jaurès, Georges Clemenceau, and Charles Péguy joined forces on behalf of Dreyfus, Lazare had thrown himself body and soul into the battle. His anarchist convictions help explain his decision—after all, while ruthless in his treatment of the Republic, Lazare was always a committed republican. The revolution of 1789, which led to the first French Republic, represented to Lazare everything that was great and good for humankind. Fidelity for the trinity of revolutionary ideals—liberty, equality, and fraternity—was particularly great among the Jews of Nîmes, a well-established minority living in a town that was itself, religiously speaking, a minority within the country at large. And as Dreyfus’ arrest made clear, safeguarding these vaunted values required the constant vigilance of all French citizens, Jews and anarchists as well as Catholics and conservatives.

With France flooded by anti-Semitic sentiment in the wake of the affair, Lazare’s politics led him on an unlikely path back to his Jewish roots. In 1896, he issued his incendiary pamphlet A Judicial Error: The Truth About the Dreyfus Affair. In both its biting style and merciless analysis, the brochure anticipated Zola’s more celebrated J’Accuse, which would not appear for another two years. Captain Dreyfus, Lazare declared, was the victim of the lies and machinations of officials at the highest levels of the army and government. Unlike Zola, though, Lazare homes in on the matter of Dreyfus’ religion. “It is because Dreyfus was Jewish that he was arrested,” he roared, “because he was Jewish that he was judged, because he was Jewish that he was condemned and because he is Jewish that the voices of justice and truth have fallen silent.”

The silence that greeted the pamphlet’s publication left a deep impression on Lazare. Few friends and colleagues on the Left rallied to his call, while anti-Semitic newspapers pummeled him. By 1898, when Dreyfus was brought back from Devil’s Island to France for his retrial, Lazare was prepared to see not just the captain but also himself as the “symbol of the persecuted Jew.” The same anti-Semitic frenzy that sparked the Zionist epiphany of Theodor Herzl—who covered Dreyfus’ public degradation for a Viennese newspaper—spurred Lazare’s conversion as well. Deeply impressed by Herzl’s book Judenstaat, Lazare had come to a conclusion similar to his Austrian counterpart: Despite their best efforts to assimilate, Jews would always be reminded by the world that they remained Jews. It was a far cry from his anarchist beginnings.

Like Herzl, too, Lazare abandoned his belief that Jews could assimilate into a secular republic like France. Yet it soon became clear that this was the only position they did share: Lazare never surrendered his radically egalitarian ideals and instead simply channeled them into his particular understanding of Zionism. As his biographer Nelly Wilson observed, Lazare believed that just as the Jew will never succeed to assimilate to French society, he must also never allow himself to assimilate to its unjust social and economic order.

Herzl’s more conservative vision carried the day, perhaps in part because Lazare did not live long enough to carry on the fight. He died, most probably of cancer, in 1903. The 200 mourners who gathered at his grave at Montparnasse were, along with a few anarchists, mostly immigrant Jews from eastern Europe. Five years later, a statue was erected in Nîmes’ central park, the jardin de la fontaine, to commemorate Lazare’s achievements. Thirty years later, it disappeared under the watch of the Vichy regime.

Should you ever visit the garden, take a minute away from the ruins of the Temple of Diana and walk toward the eastern gate. Against a rock wall and behind leaves and branches you will find a plaque where the statue once stood. Its inscription would not embarrass Lazare: “A statue once stood here,” it reads, “dedicated to a man who, in dangerous times, defended the rights of man trampled under in the person of Dreyfus.”

Robert Zaretsky is professor of history in the Honors College, University of Houston, and the author, most recently, of Albert Camus: Elements of a Life.

Liel Leibovitz is a senior writer for Tablet Magazine and a host of the Unorthodox podcast.

Robert Zaretsky is professor of history in the Honors College, University of Houston, and is a contributor to The Occupy Handbook, to be published next month by Little, Brown.