The Chained Reader

How the logic of machines makes us less human

RDImages/Epics/Getty Images

RDImages/Epics/Getty Images

RDImages/Epics/Getty Images

RDImages/Epics/Getty Images

Something strange happened the first time I encountered an article online that I wrote for a print magazine. The article was an old-fashioned feature that had taken me months to report, then perhaps six weeks to write, plus another six to eight weeks to edit and rewrite with the help of capable editors, copy editors and fact-checkers who helped give the magazine prose of yesteryear its distinctive glossy finish. The layered process by which such texts were produced meant that I had read through my article with close attention over a dozen times before it was published, by which point I could recite long passages of my prose by heart.

Yet the sentences and paragraphs that I saw swimming before me on the screen clearly weren’t mine. Rather, they read like a raw, unfinished version of my actual article—an undergraduate parody of something that took me months to write. I was gesticulating wildly where I should have been quiet, drawing attention to myself at weird junctures, and making weird faces at the camera. Points I had made in a sensible, even-toned fashion had been washed out or faded into the background, making it hard to follow my argument. I was living the dream of going into an important meeting with no pants on, except I wasn’t dreaming. Hundreds of thousands of people would soon be seeing this unwonted version of my prose self, stammering and half naked.

There had to be a rational explanation for the disaster on my desktop. My first guess was that a well-meaning copy editor at one of America’s most august magazines had accidently uploaded the wrong file, causing an early editorial draft from months ago to populate the magazine’s website. On the verge of calling my editor to alert her to this embarrassing error, I thought to compare the text onscreen to the final galley proof, which I had printed out on paper. (The editing process at print magazines back then involved a succession of proofs that showed the author and her editor the text of the article in a progression of magazine-width columns, then layouts.) Trembling, I located the final proof on my desk, and sat down to reread the product of months of my labor.

Very soon, I found that my blood pressure was returning to normal. The galley proof was identical to the text I remembered writing—serious in the right places, funny in others, embedded in an argument that made logical sense. In other words, it read like the product of months of work, supervised by other high-end professionals whose job was to pay close attention to what they read. What happened was now crystal clear: Someone had indeed published an early, half-finished draft of my article on the magazine’s website.

Then I thought to compare the text on the page to the text on my screen. Word for word, they were exactly the same. I was shocked. What happened? Why did a text that read so well in galleys read so shambolically online?

The uniquely powerful insight of the 20th-century discipline of cultural anthropology as formulated by the great French thinker Claude Levi-Straus was that culture is a closed system. A tribal mask hanging on the wall of a hut in Africa or New Guinea has meaning within the culture of the tribe that produced it, which is bound up with their social structures and cosmology. Hang the same mask next to a Picasso in a white-walled room in MOMA, and it becomes a different object, embedded within the cultural system that contains 20th-century Western art. Culturally speaking, the two masks are wildly and indeed irreconcilably different from each other—even if, physically speaking, they are the same mask.

So too with the act of reading. Like every other human activity, reading is a culturally bound activity, whose meaning is determined by its relation to the larger cultural system in which it occurs. To take a simple example from the history of reading, a medieval monk poring over an illuminated manuscript of the New Testament might appear to be engaging in an activity familiar to all of us: reading. However, if you were to ask that monk what he was doing, he might explain to you that he was speaking aloud the written word of God in order to ensure that it was untainted by human error. Ask the same question of an 18th-century Enlightenment philosophe poring over the exact same manuscript, and he would probably give you an answer related to the application of universal reason or critical inquiry. The activities of both readers, while they might superficially look the same, acquire their meaning from different cultural systems, which constitute the act of reading in entirely different ways.

In the nearly six centuries since the invention of the printing press, the collapse of the dominance of the Catholic Church over Western intellectual life, and the emergence of species of radical selfhood as expressed and propagated through such varied technologies as universal literacy, easily portable books, and cheap hand mirrors, we have become familiar with the idea of reading as a private, inward act of communication between the individual reader and the author of a text, which is part of a cultural system that we call “humanism.” As a humanist reader, I pick up a book, and go sit in a chair. As I scan the lines on the page, my lips don’t move, while my eyes tend to move down the center of the page, while also moving from left to right. Because I am musically inclined, I tend to be especially sensitive to percussive consonants and the varying lengths and punctuation of sentences. If the author of the text gains my trust by demonstrating intelligence and skill—a sense of humor also helps—I sink into a kind of reverie, in which I begin almost semiconsciously to fill in gaps in the text, using my own experiences to extrapolate a complex inner or external landscape from a brief description of a character’s perceptions or dress. In doing so, I become a kind of co-author of the text I am reading, which means that in some sense the book I am reading will always be unique to me.

In brief, my thesis here, based on three decades of professional activity as a writer and editor, is that we are at a moment of disjunction in the history of reading, driven by a technological shift that already seems to be as consequential as the birth of the printing press, a shift whose magnitude was already present to me 15 years ago when I had my dizzying encounter with my own text. The answer to the mystery I faced that day was contained, I realized, in my browser. The text I read in the galley proof had been written for the printed page, where it was surrounded by a halo of empty and inert white space. It was like playing an instrument in a concert hall where the audience sits in silence, waiting until the breaks to applaud.

The browser wasn’t so polite. In fact, it was constantly tugging at the reader, reminding him or her of the many other interesting articles they could easily read instead of mine, in the rest of the magazine and throughout the entire internet. To aid the reader in making his or her engagement with my text as fleeting as possible, words and phrases within the text were helpfully underlined, in blue; when you clicked on them, they took you to other websites in order to explore, say, the rich history of a plant I had happened to mention in passing, and which had no meaningful connection to the rest of my article, or even the subject of my article. Those websites linked to articles on other websites of varying quality and styles with no apparent connection to each other, except for the fact that they were also located somewhere on the internet. If the expected relation between the text and the empty spaces of the galley proof reminded me of playing a violin in a concert hall, reading the same text on my browser felt like trying to play a sonata over the din of Grand Central Station during rush hour.

The arrival of large globally networked social media platforms powered by AI, which is the context in which 21st-century humans do most of our reading, has further fractured the more than 600-year-long intimate relationship between the humanist reader and the author, to the point where it is becoming difficult to speak about the reader’s experience of a text independent of the social media response, which is being consistently gamed by the hidden hands of political operatives, large corporations, intelligence agencies, and other arms of the state. What these forces have in common is that they seek to interrupt the dialogue inside our heads and replace it with catechisms about what we can say, think, believe, how we are to identify ourselves to others, and what we should be. By forcing the reader to internalize an algorithmically powered chorus of yeas and nays, which are being constantly manipulated by external actors, the platforms can no longer lay claim even to the noisy neutrality of Grand Central Station. Instead, they have become instruments of interpretive enforcement backed by the built-in sanctioning mechanisms of social disapproval, ostracism, or worse. In addition to radically altering the nature of how human beings communicate, exercise power, and accumulate wealth, social media therefore augurs a fundamental transformation of the activity of reading, reversing the radical possibilities for the free play of individual minds that have been encouraged for over 600 years by the accumulated social power and credit made possible by the technologies of the printing press and the printed page, and by the practice of silent reading.

From antiquity up through the 20th century, reading was more than a platform for aesthetic expression or self-centered reveries. Reading was also an important source of knowledge and insight for powerful men as well as some women, a practice that was pursued not only for its literary, religious, and emotional rewards but also for its sheer practical utility. Reading was as important a source of insight for Marx and Lenin and their followers as it was for Charles Darwin and as it had been for Aristotle and Thucydides. The ways in which the subjectivities of readers of power interacted with those of the authors they found useful were quite different from the ways in which monks read scripture, or social media users communicate online.

But before sketching out some of the salient features of the nature and scale of the changes we are currently going through, and the new habits of reading that they are producing, it is necessary to remove a distraction that pops up whenever the conjunction of technology and reading is raised. Namely, whether machines powered by AI can think. There is no question that AI is an extraordinarily powerful human tool that may be used in ways that may not always appear to accord with the wishes of their ostensible human masters. But as the philosopher John Searle pointed out more than 35 years ago, consciousness is a characteristic of human functioning that is inherent in the specificity of the human biology. To argue that AI can or can’t attain consciousness is therefore a simple category error; moreover, it contradicts decades of experience in teaching machines how to “think,” which is a word that describes a fundamentally human activity. I am therefore not concerned here with the question of whether machines can think, but with how machines are changing how humans read.

Most social media users reject the premise that they generally behave the way that the software that governs their platforms instructs them to behave, or that their behavior as information-seekers on large networked tech platforms is anything other than an expression of their own internal thought processes. By scrolling through their phones, and “liking” or attacking stray phrases tweezered from articles that were largely or entirely engineered for that purpose, they believe themselves to be gaining valuable information about the world and becoming smarter, better-informed members of their social group—thereby engaging in an act of self-definition that is increasingly circumscribed by social media platforms, in a closed loop.

Yet seen from the perspective of the platforms that attract and hold the attention of users through gamified loops, social media users may as well be networked bots whose activities are profoundly mediated—if not entirely predetermined—by the platforms that support and guide their activities, to the point of framing their thoughts and actions and defining the meaning and reach of the language they use and consume. And since machines by definition can’t think, no one in these algorithmically driven systems can be said to think—which is one reason why the common wisdom of entire classes of “experts” who populate these platforms is at once so remarkably uniform, and so often gob-smacked by reality.

Platforms animated by machine logic turn people into functional subroutines, repeating chunks of language in response to prompts. By doing so, they help the machines to sort categories of information that are unique to human beings into machine-appropriate buckets. The auto-complete function that is now built into every platform from Google to X is merely one obvious way that machines are breaking down the individuating qualities of language into a more impoverished and grammatically rigid—that is to say, less human—language that they can more easily predict. These activities, especially when repeated dozens of times per day, bind their authors, i.e., you, to larger machine-friendly language complexes that train their human users to uncritically accept judgments and prompts that are reinforced by the real-time networked effects of millions of other machine-mediated human users. The results of this process can be fairly judged by the fact that the sentences produced by social media users repeatedly fail basic tests of internal logic and external proof in a way that is frankly impossible to imagine in any recognizably humanistic culture of critical thinking and reading.

The world’s richest man understands all of the above, because it is essential to his business. Tesla, Elon Musk’s electric car maker, produces real-world cars that run on batteries that store electricity. However, the desire for cars that operate on such technologies—which is heavily subsidized by governments around the world—is a social product, which is largely generated by memes. Elon Musk is able to get individual investors and large institutional investors alike to invest hundreds of billions of dollars in his stock because Tesla is a meme. The Tesla meme is in turn linked to the meme-world existence of Elon Musk, who creates, shapes and broadcasts his image via social media, which in turn allows hundreds of millions of other people to participate in his work of meme-production—and real-world production—by buying Tesla cars and Tesla stock. Eliminate the linked universe of electric cars, Tesla and Elon Musk from meme-world, and hundreds of billions of dollars in real-world value would vanish.

Elon Musk paid $44 billion for Twitter because he had every reason to believe that a platform he had used to build his personal brand would be turned against him. That’s because Musk is a prominent target for charges of spreading “disinformation,” which is a term developed by establishment actors acting in concert with each other to censor speech. The sanctions with which they threatened Musk, which included limiting his reach on social media platforms or kicking him off such platforms entirely, would have most likely crashed his car company. When seen this way, $44 billion was a very reasonable price to pay as a one-time insurance premium against a type of catastrophic damage that directly threatened a set of companies valued at over $1 trillion.

Still with me? Great. Now focus for a moment on how you are reading this article. If you are over the age of 40, you will soon recognize that your eyes move across the screen in front of you very differently than they move across a printed page of text; I’m assuming that you still read physical books in order to buy more time for my argument, though the numbers suggest that you don’t read printed books very often, even if you still buy them. In any case, the screen-reader in you is demonstrably more distracted. At the same time as you are unlikely to be able to remember anything you are reading, your attention is heightened, and made more anxious, by your anticipation of the release or denial of a warm jolt of serotonin that signals social approval or belonging. Because, from the platform’s point of view, the texts you consume are simply semisentient spyware, your attention is also accompanied by the—quite accurate—sense that someone is looking over your shoulder. What was once the private, interior experience of reading no longer feels quite so private. The transformation of reading into a public experience means that it is subject to different rules; what is acceptable in private is no longer encouraged or experienced as appropriate.

Elon Musk paid $44 billion for Twitter because he had every reason to believe that a platform he had used to build his personal brand would be turned against him.

That’s assuming you are human, of course. From the perspective of the text and its purveyors, it matters little whether you are a mechanical subroutine expressed in a string of code or a human user whose platformed reading activity is a functional adjunct to a larger machine process. Statistically speaking, most reading on the planet today is not being done by humans, whether men of power or social media users talking about Taylor Swift. It is being done by machines, which are therefore inevitably reshaping and redefining the activity of reading for all its practitioners, machine and human alike.

Being a romantic at heart, it is hard for me to dismiss the humanistic yearning for a culture of reading which will very likely soon be unrecognizable except to monks on Mount Athos. As an author, I prefer to inhabit a universe in which every sentence I read is the recognizable product of a set of instructions which function as a kind of authorial DNA, containing the capacity to uniquely populate the many universes that we carry around with us as we interact with other humans, and attempt to inhabit a shared reality.

The practice of silent reading, on which this modern humanistic understanding of reading, and also of what it means to be human, relies, is perhaps first noted by Horace, the leading Roman lyric poet of the age of Augustus, who wrote of “reading and writing which I like to do in silence.” For Horace, as for at least a minority of his fellow Roman readers, silent reading was a preferred practice, distinguished from other types of reading, and which had existed for centuries before the poet’s birth. One of the reasons that Roman authors are largely intelligible to modern readers like ourselves is that they read more or less the way we do, and wrote with readers who were at least in some ways like us in mind.

There was nothing necessary about Horace’s audience or the poet’s habit of silent reading, though. The end of Rome’s golden age sent habits of text-based reading moving backward for centuries, until the habit of silent reading by individuals—along with the accompanying practice of writing with interword spaces—became virtually unknown. In Europe, the task of separating out individual words was left to a priestly class of scribes who lived in monasteries, where the vast majority of written texts resided. Monks could mostly read; very few other people could. The monastic Rule of Benedict instructed monks to read in silence, so as not to disturb their fellow monks.

The practice of silent reading also went to the heart of a philosophical debate of great importance within the Church. The debate began more or less in the fifth century, when the Church emphasized and strengthened the separation of the written and the spoken word. The need for this separation arose in part based on the great philosopher Augustine’s understanding of letters as the signs of sounds, meaning that written letters and words were merely a means of communicating oral language through script. But the seventh-century monk Isidore, regarded as the last great scholar of the ancient world, disagreed with Augustine: He understood letters as signs without sounds. Letters, he believed, were signs of things, allowing written words to signal directly to the mind through the eye. Spoken language was therefore understood by the Church as separate from, and inferior to, written language; a diminishment of God’s word.

Isidore won. Yet as the historian Paul Saenger writes in his landmark essay “Silent Reading: Its Impact on Late Medieval Script and Society,” “the ancient world did not possess the desire, characteristic of the modern age, to make reading easier and swifter because the advantages that modern readers perceive as accruing from ease of reading were seldom viewed as advantages.” As far as the Church was concerned, the longer the reader was occupied with God’s word, the better. So while the Church itself privileged silent reading in theory, it confined the practice to carefully defined spaces and occasions. In fact, the more the Church could limit and control the relationships between individuals and texts, the better.

Yet the doctrinal primacy of silent reading within the Church perhaps inevitably led to the spread of the practice among laymen, which began at least a half century earlier in Italy, the home of the Church, than it did in northern Europe. “The new privacy afforded by silent reading had dramatic and not entirely positive effects on lay spirituality,” Saenger writes. Unsurprisingly, one consequence of the spread of the practice of silent individual reading was a flourishing trade in erotic printed art, not dissimilar to the vast popularity of sites like Pornhub on today’s internet.

Saenger’s essay is a landmark in the history of literacy because it fractured the largely unexamined assumption that reading is an innate human capacity whose expression has remained more or less the same over time. Instead, Saenger demonstrated that the activity of reading had changed radically over time; it was also his assertion that the changes he chronicled were selected for by the organization and the capacities of the human brain. For example, Saenger showed that there are discrete systems in the brains of English speakers for the aural understanding and silent visual understanding of language, which are in turn dependent on the spatial organization of the text. If you give a text typed in capital letters with no word separation or punctuation to a class of fifth graders, they automatically read it aloud, which is a continuation of the habit by which a child sounds out words syllable by syllable in order to gain access to meaning. Saenger concluded that, “Only scripts that provide a consistently broad eye-voice span to oral readers can sustain rapid, silent reading as we know it,” a practice he defined as “reference reading”—meaning the rapid perusal of texts in order to extract specific, useful information. It was Saenger’s thesis that reference reading was prevalent within, and probably essential to the development of, advanced civilizations in both the East and the West.

The practice that Saenger defined as “reference reading” was hardly new. It was beautifully described by the younger Pliny in his letter (Letters, 3.5) about the way his uncle read to compile notebooks (and also his Natural History) and was traced through the centuries by the scholar Ann Blair in her masterful history Too Much to Know. However the use of this particular technology of reading was largely confined to small circles of mostly very well educated scholars, scientists, and others who read widely, and for a purpose.

If one helpful precondition for reference reading is silence, the other was standardized letters and punctuation that made it possible for the extractive eye to scan texts at high speeds. Operating at the edge of the Latin-speaking world, the scribes of the Anglo-Saxon islands sought to preserve and even augment the power of written language by reintroducing spacing between words, which the Romans had used to facilitate speedy access to the text, while restricting variant forms of letters—innovations that led to the development of many of the standardized typefaces in which books are printed today. “The reintroduction of word separation by Irish and Anglo-Saxon scribes,” Saenger wrote, “constitutes the great divide in the history of reading between antique cultures and those of the modern Occident.” By lessening the cognitive burdens of text recognition and word-separation, the new standardized scripts made rapid, silent reading possible by reducing the time it took to convert signs into words, even before the inventions of the printing press and movable, standardized type.

As the innovations of the Irish and British monks reached the European mainland in the 12th and 13th centuries, the spread of the new ecclesiastical language software was greeted with equal measures of delight and apprehension, a tension that was perhaps best expressed by the 14th-century Italian poet Dante Alighieri in his narrative of the literary lovers Paolo and Francesca. “One day, for pastime, we read of Lancelot, how love constrained him; we were alone, suspecting nothing. Several times that reading urged our eyes to meet and took the color from our faces ...” the poet writes. What happens next of course is that the lovers kiss, putting their mortal souls in danger.

Dante’s lovers were victims of the morally dubious act of reading for pleasure, which is inherent in the intimacy of the encounter with the text. The story of Paolo and Francesca, accompanied by the poet’s graphic images of the tortures of hell, was itself meant to be read in private by lay readers, some of whom no doubt fell victim to the same corruptions as Dante’s lovers.The idea that reading can be a double-edged sword is therefore nothing new. What is new today is the rebalancing of the social forces that are arrayed against the free imaginative activity of the individual.

Today, we celebrate the Renaissance as the moment when the power of the individual consciousness began to gain significant traction against the desire of the Church to stand as the sole legitimate arbiter of truth. Reading helped to open up the inner spaces in which men and women could think independently about their own lives and their place in the universe. As a consequence, we have come to think of those inner spaces, as figured through the act of silence reading, as the places where a significant part of our humanity resides. The question is, how long is the centurieslong balance between the sovereign imaginative authority of the individual and the pressure of large institutions and networks likely to hold in an age of new technologies that relentlessly colonize our inner lives, whether on behalf of the large corporations that fracture our online activities into marketable packets of data, or to feed the surveillance nets of spy services and other arms of the state, which see self-guided human thought-activity as a danger to their earthly supremacy, and even to the survival of the planet itself.

In his classic essay “The Humanist as Reader,” the historian Anthony Grafton more or less dates the open celebration of lay reading to a letter written in 1513 by Nicolo Machiavelli to his friend the Florentine humanist and diplomat Francesco Vettori:

Leaving the wood, I go to a spring, and from there to my bird-snare. I have a book with me, either Dante or Petrarca or one of the lesser poets,” Machiavelli wrote. “I read about their amorous passions and about their loves, I remember my own, and I revel for a moment in this thought. I then move up on the road to the inn, I speak with those who pass, and I ask them for news of their area; I learn many things and note the different and diverse tastes and ways of thinking of men.

In daytime, the book in the reader’s hand is like a net, capturing the reader’s own memories as well as the observations and perceptions of other humans who intrude on the reader in the act of reading. The night offers a more direct and intimate kind of encounter, in which the philosopher converses directly with the greats. “I am not ashamed to speak to them, to ask them the reasons for their actions,” Machiavelli continues, “and they, in their humanity, answer me; and for four hours I feel no boredom, I dismiss every affliction, I no longer fear poverty nor do I tremble at the thought of death ...”

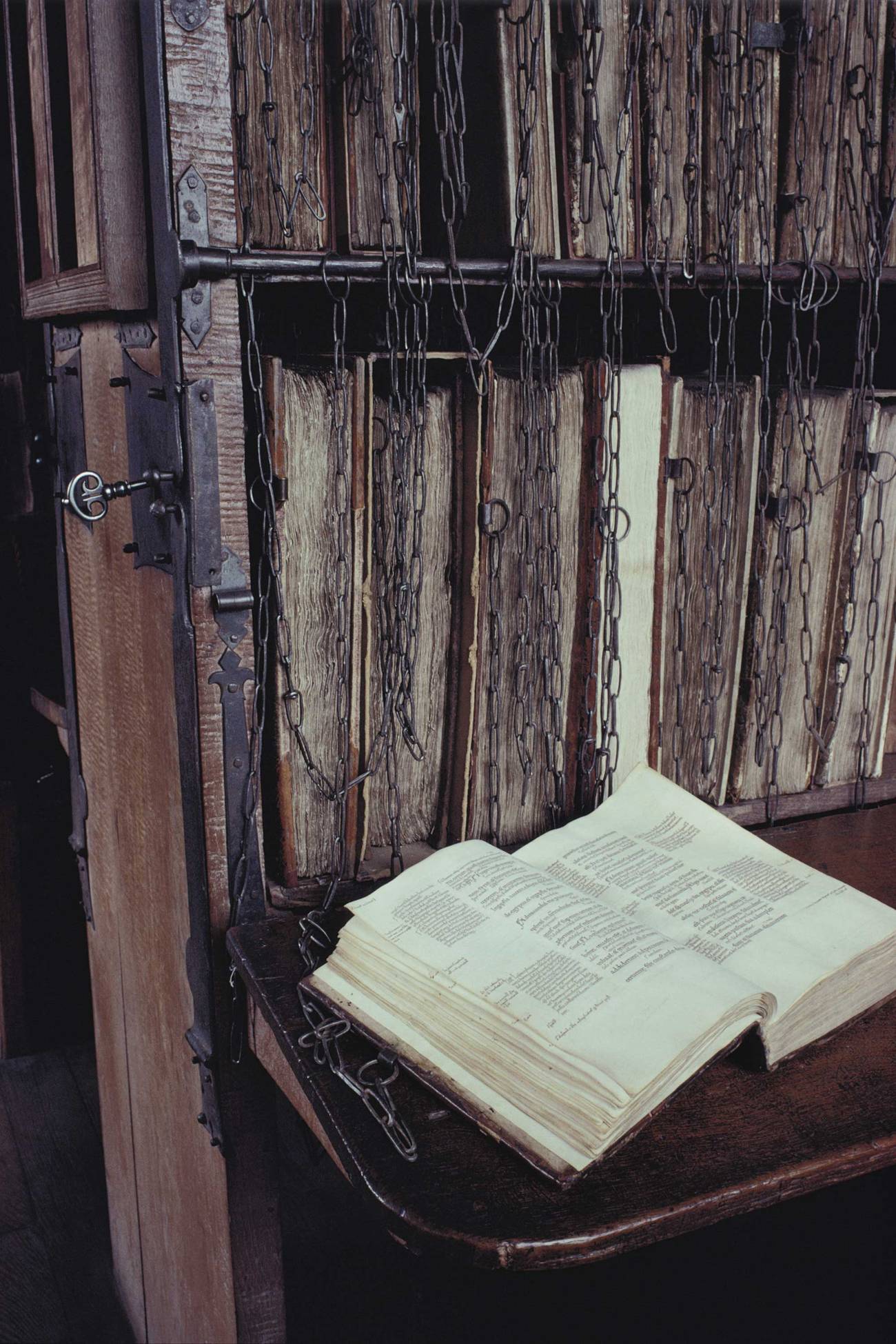

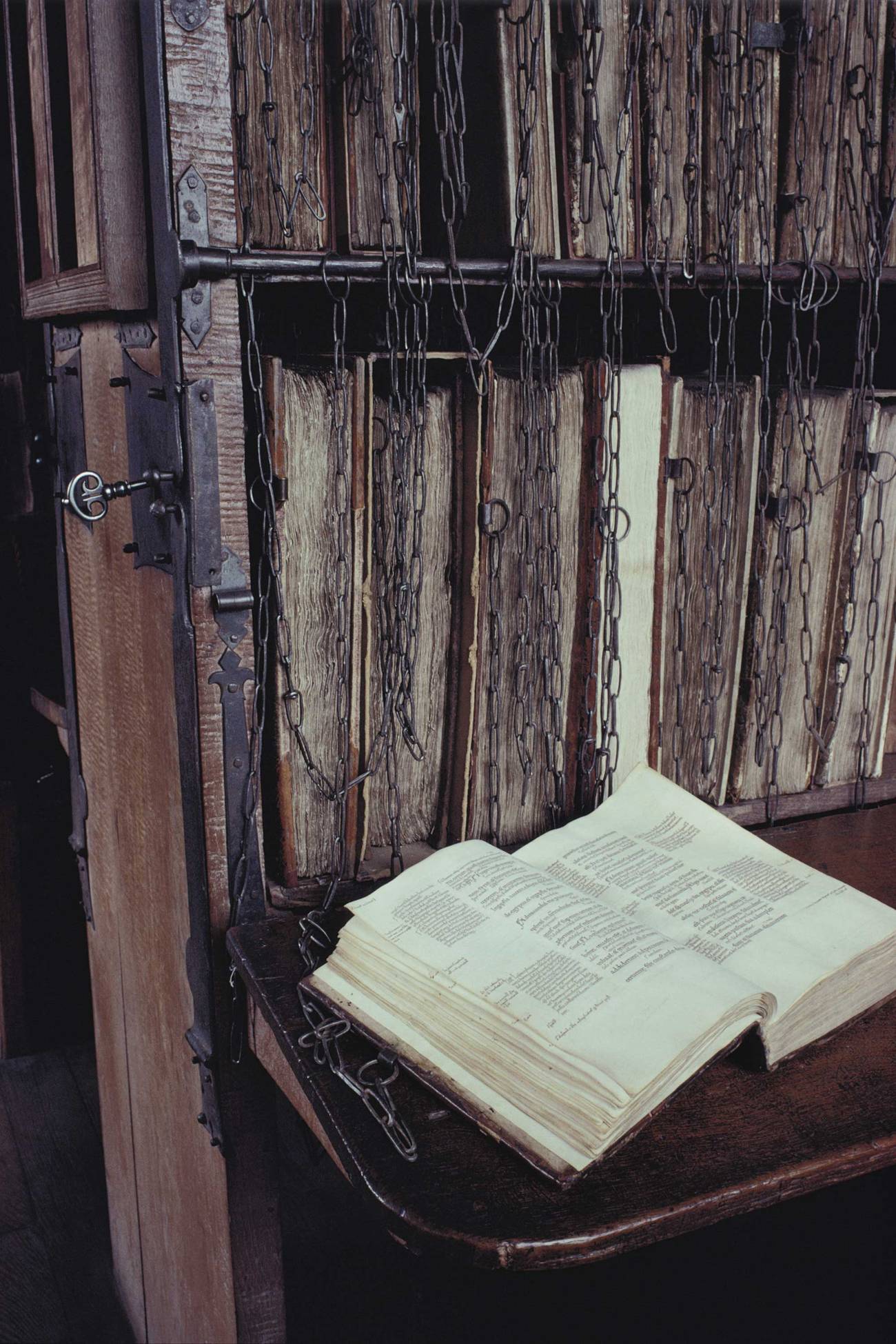

Renaissance humanist literature is replete with such moments of bibliophilic transcendence, from Petrarch carrying his copy of Augustine to the top of Mount Ventoux to the scene described by the whores in Aretino’s Ragionamenti of young gallants clustering beneath a young woman’s window with their copies of Petrarch. Newly liberated from monastic library shelves where they were often literally kept chained by monks, books became mobile, personal possessions, which their owners used to define themselves. As Grafton felicitously puts it, humanists personalized their books the way California teenagers of the 1950s personalized their cars, by systematically annotating as they read. Annotations themselves became a quasi-formal literary genre, with Montaigne’s marginal responses to Plutarch and Guicciardini being including in his famous Essays.

The reach of the humanistic revolution that Grafton and his fellow early Renaissance scholars have chronicled was greatly aided by the invention of the printing press somewhere around 1440 by the German printer Johannes Gutenberg. The printing press made possible the spread of humanistic scholarship and Protestant individualism, which combined to shape modern reading habits by diffusing relatively cheap copies of books to relatively large numbers of people. Martin Luther, the father of the Protestant churches, proclaimed printing to be “the ultimate gift of God,” while John Foxe, author of the widely printed Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, gave thanks for what he called the “divine and miraculous invention of printing.”

Yet regardless of the growing number of printing presses in Europe, and the importance of printed material in both spreading and combatting the new Protestant faith, reading remained an activity restricted to an elite. The historian Rolf Engelsing estimates that in Germany around 1500 somewhere around 3%-4% of the population could read, while David Cressy estimates the English literacy rate during the 16th century being somewhere around 10% for men and 1% for women. In Venice in 1587, 26% of boys and 1% of girls attended schools in which they were taught to read.

So how did these early modern readers, however few or numerous, actually read? The sermons and pamphlets that made up a large proportion of printed matter in the first two centuries after the printing press was invented seem to be more scripts than texts, intended to be read aloud to audiences that were mostly composed of illiterates. Sounding not unlike the Catholic Church leaders he so fervently opposed, the Puritan leader John Calvin told the printer Jacques Roux of Geneva that he was reluctant to have his sermons printed because of the confusion that would be engendered by the differences between the written and the spoken word. The emphasis of the new churches on catechisms further underlines the continuing importance of orality even among Protestants. Yet simply by holding books in their hands, and enshrining them in their homes, Protestants and their children were being prepared for lives as readers in a way that Christians of previous generations were not.

The Catholic Church understood the nature and the size of the threat to its authority posed by the practice of private reading. By the Council of Trent in 1546, at which the Catholic Church recognized the Latin Vulgate Bible as the one true version of Scripture, the threat posed by the proliferation of printed books being read in private was clear. “No one, relying on his own skill, shall—in matters of faith, and of morals,” the Church proclaimed, “presume to interpret the said sacred Scripture” contrary to the Church. In 1564, the Church launched the index of prohibited books while warning that only “learned and pious men” should be allowed to read the Bible in translation; laymen would still be allowed to read the Bible in Latin. In 1593, Pope Clement, a staunch opponent of disinformation, withdrew permission for laymen of whatever levels of piety to read the Bible at all, a prohibition that lasted until the middle of the 18th century.

The genie of reading that the Church released through its innovations in standardizing texts could not so easily be put back into the bottle. A flood of Protestant sermons, natural histories, works of scientific speculation and discovery, works of political philosophy and economy followed, along with memoirs, novels and other texts that were printed cheaply on machines that, if needed, could be hidden in barns and basements. The German historian Rolf Engelsing has documented the radical expansion of available reading material in Protestant areas of Germany, from a small cabinet of approved books to an extensive, varied reading diet. Meanwhile, as “the new bourgeois agents of culture increased in number,” Engelsing wrote, they no longer could find adequate employment; “these ‘free-floating intellectuals’ constituted a potential for unrest through their explicit questioning of the traditional system.”

One result of the changes that Engelsing documents is what the German political philosopher Jurgen Habermas called the “structural transformation of the public sphere,” a new space in which private people assembled into a public, structured by printed matter and the resulting cloud of discussion among readers and their listeners in streets and coffee shops. The new reading public with direct or indirect access to the printed materials that helped structure the new “public sphere” included urban servants, who had free time; access to light; small budgets to purchase printed materials; and easy access to newsstands and booksellers. Chambermaids read comedies, novels, and poems, while soldiers in urban barracks preferred novels and erotica. Much as the internet has done today, the wide availability of written material both democratized the practice of reading and made it shallower, as the Renaissance gave birth to much greater numbers of readers and listeners with much less average capacity for critical engagement with the texts that they read, when compared with their learned, often noble predecessors.

Sometime around 1770, prevailing Enlightenment modes of reading deepened and became more empathic, resulting in an even larger audience of readers whose desire and ability to buy books was matched by a new and overwhelming desire to make contact with lives behind the printed page. Novels like Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther in Germany, Rousseau’s La Nouvelle Heloise in France, and Samuel Richardson’s Pamela in England became wildly popular narcotics that fed national reading manias. “No lover of tobacco or coffee, no wine drinker or lover of games, can be as addicted to their pipe, bottle, games or coffee-table as those many hungry readers are to their reading habit,” wrote the Erfurt cleric Johann Rudolf Gottleib Beyer in 1796.

Which all seems pleasant enough. What this short-hand account of the Gutenberg revolution leaves out, of course, is the terrifying physical destruction and bloodshed that accompanied these changes in reading habits. In England, the broad diffusion of printing presses led to the decadeslong anti-monarchical revolution led by Oliver Cromwell. The Thirty Years’ War, fought between Catholic and Protestant believers and their hired armies in Central and Eastern Europe remains the single most destructive conflict, on a per capita basis, in European history, including the First and Second World Wars. It was readers, particularly readers of sentimental novels, and the new emotionally driven picture of humanity they made popular, who expressed their dissatisfaction with the old regimes in France and Germany, and, harnessing the power of the printing presses, swept them away.

Today’s revolution in reading being spurred by the advent of digital technologies may turn out to be even more powerful than the Gutenberg revolution. If the spread of printing presses, combined with the spread of cheap hand-held mirrors, made available to millions of people a new sense of themselves as individuals, and as the authors of their own stories, which were inherently worth reading about and listening to, we can only wonder at the power inherent in billions of iPhones and other smartphone devices which combine a printing press, in the form of access to social media platforms, and a mirror, in the form of ever-more-powerful smartphone cameras, with which users endlessly record and broadcast selfies. Network billions of these mirrors together, and put them in real-time communication with each other, and it seems clear that we are looking at a species of transformative, technologically driven change that reaches deeper inside our heads and hearts and moves at a far greater velocity than anything human civilizations have ever experienced. At the very least, history suggests that the next century may be as bloody as the century that followed the Gutenberg revolution, which gave Europe the Thirty Years’ War.

Governments and other state actors are rightly afraid of what these changes may mean for existing social forms and power structures, though seeking to constrain technology by chaining hundreds of millions of minds has not proved itself to be a particularly productive strategy. What does seem clear is that we are approaching a large-scale social crisis that we are bringing upon ourselves, in part through our reluctance to acknowledge the extent to which how the digital revolution and the new habits of reading it is inculcating are themselves radically altering the institutional and intellectual framework of Western liberal societies. The extent to which our inner lives are being flattened and made public—meaning less subject to our own control, and more accessible to direct manipulation and censorship by state and quasi-ecclesiastical actors—should give us pause. The idea that we are exchanging modes of reading that have been largely dominant in Western societies for the past few centuries for new technologically mediated modes of reading that have more in common with the centuries in which books were chained and the life of the mind was seen as a threat to the spiritual order maintained by the Church should not strike any sane observer as a hopeful or desirable development.

It was readers, particularly readers of sentimental novels, and the new emotionally driven picture of humanity they made popular, who expressed their dissatisfaction with the old regimes in France and Germany, and, harnessing the power of the press, swept them away.

Machine-based reading, which is the prevent mode of reading today among both humans and machines, was born in 1854, when the English mathematician George Boole published The Laws of Thought, which converted the FALSE and TRUE statements at the heart of Aristotle’s logic into two digits—zero and 1—that could be crunched by algebraic equations. Eighty-three years later, the American mathematician and electrical engineer Claude Shannon gave life to Boole’s insight when he posited that the electrical off/on switches of a differential analyzer could be used to animate Boole’s 0/1 bits. Accompanying this realization was the insight that on/off switches could be used to automate Aristotelian syllogisms: One arrangement of off/on switches could calculate AND, a second could calculate OR, and a third could calculate NOT. While the clunky switch-arrangements that Shannon drew up in 1937 have shrunk to miniscule transistors, multiplied into parallel processors, and used to perform increasingly sophisticated styles of mathematics, the arithmetic logic unit (ALU), which is the core design of a computer’s brain, remains an automated version of Aristotle’s AND-OR-NOT logic, as expressed by Boole and given concrete physical form by Shannon.

What is important to understand here is that the machine-centered definition of reading or “reading” is different in kind from humanistic notions of reading that we have been discussing, which involve the two-way encounter of the (human) reader with a closed system of symbolic signification we call a text, regardless of whether that system appears on a stone tablet, a piece of parchment, a printed page, or an Apple Retina screen. Through the act of reading, as suggested at the top of this essay, the reader produces the text, just as the text creates the reader; author and reading are bound together by deeply coded sets of instructions about which words matter more than other words, and where to look next, by which a text is produced, and which govern the ways it can be decoded. These instructions refer both inward, toward the closed system of the individual text, and at the same time outward, toward the human experience of real-world sensations and events, resulting in the distinctive form of interiority that we call reading. The individual reader’s attention can be altered by the consumption of stimulants or narcotics, or by the distant tinkling of a Chopin sonata, or by a Bill Evans bass line coming through an open window. Yet we recognize all of these varying experiences of a text as reading, just as we recognize that no two readings of the same text are ever exactly alike.

Machines deal with texts by “sorting,” meaning that they “read” by breaking the strings of symbols apart and putting the pieces into buckets. They can’t escape the mathematical present tense in order to perform causal reasoning, which means that they can’t think like historians or novelists, or like human readers. And it shows.

Here is a sample of a novel, written by an AI “deep learning” network: “It took a lot of time, maybe hours, for him to get the money from the safe place where he hid it, so he brought it back in a bundle and left it on the table. Then he noticed the money that had been hiding in the bed, and began walking toward the bed with a large bundle.”

What’s wrong here? As Gary Marcus and Ernest Davis explain in their essay “Rebooting AI,” while the phrases of the AI detective noir feel fluent, the ideas that animate them are incoherent. Where does the second bundle come from, and what does it have to do with the bundle containing the money that the protagonist has placed on the table? Is the money on the table the same money that is hiding in the bed? These questions don’t have answers because machines don’t think. The spring that should be moving the story forward, connecting action and motivation, is missing, because the sentences in question are not generated by human logic, but by the machine logic of the ALU, which recognizes a statistical correlation between wallets and safe places.

While current AI systems can produce “human-seeming” effects on the page more often, by drawing on much greater processing/correlating power than their predecessors, they continue to lack what linguists call compositionality, or the ability to construct the meaning of a complex sentence out of the meaning of its parts. AI doesn’t really have any direct way of handling compositionality; all it has access to are enormous quantities of data. AI can learn that dogs have tails and legs, but it doesn’t “know” how they relate to the life cycle of a dog. Nor can it recognize a dog as an animal composed of a head, a tail, and four legs; what an animal is; what a head is; or how the concept of head might vary across frogs, dogs, and people, yet bear a common relation to bodies. What AI can do is learn to predict that the words wallet and safe place occur in similar kinds of sentences (“He put his money in the wallet,” “He put his money in a safe place”), but it has no way to relate that correlation to the human desire to protect one’s possessions.

Terry Winograd, a professor at Stanford University, tried to solve the problems of compositionality by creating a simple virtual environment consisting of a handful of objects sitting on a table. He then created a program, named SHRDLU (the second column of keys on a Linotype machine), that was capable of parsing all the nouns, verbs, and rules of grammar needed to refer to and thereby govern his tabletop world. SHRDLU could describe the objects on the table, answer questions about their relationships, and make changes to the arrangement of objects in response to typed commands. If you told it to move “the red cone” and then later referred to “the cone,” it would assume you meant the red one—a capability loudly trumpeted by AI enthusiasts. Yet when Winograd tried to make the program’s world larger, the rules required to account for the expanding number of words and their possible relationships to each other caused the system to collapse—the problem with applying machine learning to language being that words are arbitrary symbols that are necessarily embedded in human experience that animates the systems in which they produce meaning.

An answer to the problem of machine reading that does seem to work is therefore to have humans do the human part of the operation of reading—namely, to select bits of the interest to other humans, while letting machines use their vast databases and enormous processing power to do the machine part. What is sacrificed in this machine-driven and directed activity, of course, is the imaginative freedom that comes from depth of engagement with the text. “Your readers are search engines,” an agency that specializes in online reading habits informed its clients. “They’re searching for something specific 96% of the time.” According to researchers at Columbia University and the French National Institute, more than 6 in 10 people who share news URLs on Twitter don’t actually bother reading them, though one suspects those self-reported numbers represent a wild underestimation of how little social media users actually read. According to an eye-tracking study conducted by a company called Dejan Marketing, people read word-by-word online a mere 16% of the time. The average online reader, researchers found, engaged with a given piece of online material for 19 seconds, punctuated by 72 “eye stops”—producing an average attention-packet of one quarter of one second per glance. However one might describe this activity, it isn’t reading.

Seen from above, online readers are the unwitting handmaidens of the “gods of big data,” assisting slow but powerful machine learners in performing tasks that humans are better at. Increasingly, from the point of view of large social media platforms, human users are mechanical turks, sorting and identifying the equivalent of bridges and traffic lights. By privileging and rewarding our performance of these activities, the machines are teaching us a new way of reading—linear sorting, i.e., putting things in baskets. Instead of seeking to extract meaning from context in order to expand the space of one’s own inner life, which is something that humans do, social media users look to outwardly conform by extracting hot-button terms and sort them into baskets marked “good” and “bad,” while being rewarded for responding correctly to the cues they are given—i.e., the platforms are training their users to read like machines.

My own suspicion, based on more than a decade of close observation as a writer and editor of the rapid degeneration of American reading and writing habits, is that a lot of what we are seeing in the so-called culture wars in the U.S. is not the rise of a new political ideology, in the sense of a set of fixed beliefs whose adherents believe them to have explanatory power. “Wokeness,” for example, often seems less like an ideology and more like an outcome of the new culture of machine reading, in which human users are tasked with doing the grunt work of breaking down complex human experiences and feelings into the linear logic of AND-OR-NOT statements.

Devout clergy and secret policemen in all times and places, not to mention the multibillionaire owners of these new systems and platforms, might well see the introduction of this new style of reading as a positive one, in which readers are adjuncts of large machine systems governed by the surveillance state, whose function is to restrain and control human thought and behavior. For readers and writers who take pleasure in their engagement with each other through the text, these developments represent the reversal of six centuries of increasing imaginative freedom and expanding opportunities for empathy with people who might seem on the surface to be radically unlike ourselves.

It is grim to think that reading, an activity which was once understood to be a key to human self-liberation, is being transformed into a tool for circumscribing our humanity, and imprisoning minds on a mass scale.

Anyone who is loyal to humanistic values and to the humanistic practices of reading must refuse to aid the work of installing little secret policemen inside every reader’s head, and then using them to control their fellow readers. Eliminating the space in which the dialogic relationship between writer and reader occurs, by turning private thoughts and experiences into public ones on large social media platforms run according to the logic of machines feels like a markedly regressive development, both for individual humans and for the societies in which they live. The future it promises us is a glowing, hand-held version of the 20th-century’s worst totalitarian nightmares.

It is grim to think that reading, an activity which was once understood to be a key to human self-liberation, is being transformed into a tool for imprisoning minds on a mass scale. At the same time, there is no questioning the power of machines to extend human capacities in ways that we may not even be capable of imagining—like curing diseases and settling large numbers of humans on other planets. Perhaps those who question the wisdom of using humans to populate large machine platforms and surveillance networks will seem to future generations like those timorous souls who predicted that Columbus and his fellow explorers would sail straight off the earth. I doubt it, though.

What does seem clear is that the glorious inner cathedrals constructed by the monks and fantastically elaborated by generations of writers whose works were reproduced on the printed page, and which helped constitute the core of what we mean by “human,” are in danger. At best, the activity of engaging in an uninterrupted inner dialogue with a printed text will become a niche taste within the larger complex of reading governed by the logic of machines and supervised by government and corporate censors.

One of the great curiosities of old Europe are the surviving libraries of chained manuscripts, which for centuries have functioned as a powerful metaphor for the liberation of the mind through the propagation of the printed word. Now, through the new technologies of machine reading, as enforced through our increasingly censored and manipulated search engines and monopolistic platforms, we appear to be going backward, to a new era of chained readers. A new set of technologies that promised liberation from censors and gatekeepers is instead producing a tragedy of the mind, by putting a small number of oligarchs, bureaucrats, and ideologues in charge of what and how we read. Together, the new censors and their robots are on the verge of achieving a constriction of human inner space on a scale that Pope Clement, John Calvin, and other fanatics of their age could only dream of.

History enjoys such ironies. And if you don’t like it, you can always pick up a book.

Become a member of the Tablet community

David Samuels is the editor of County Highway, a new American magazine in the form of a 19th-century newspaper. He is Tablet’s literary editor.