Leonard Bernstein fell in love with the idea of Israel even before the state was established. The 27-year-old musical prodigy made his first trip to British Palestine in April of 1947, accompanied by his father, Samuel, and his sister Shirley. He had been invited by the Palestine Symphony Orchestra to program a series of concerts, and found himself smitten by the land and people of the state in making. In letters from Tel Aviv to his mentor, Boston Symphony Orchestra conductor Serge Koussevitzky, Bernstein expressed great enthusiasm for Zionism and for the musicians of the Palestine Orchestra. Maestro Koussevitzky must have been surprised and somewhat shaken by Bernstein’s passion for Zionism; after all, Koussevitzky, born into a Jewish family in Russia, had converted to the Russian Orthodox Church as a teenager. That was the only way that he could advance his musical career, as Jews were not permitted in the Moscow Orchestra training program he sought to enter. In 1942, when Bernstein first emerged as a gifted and popular figure in the classical music world, Koussevitzky urged his protégé to change his name from Bernstein to Burns. “Your name is too Jewish, and too ordinary,” he said.

But Bernstein would have none of it. Mid-20th-century America was not late-19th-century Russia, and the Boston Symphony Orchestra was a far cry from the Moscow Philharmonic. Bernstein sensed that American culture would accept performing artists with Jewish names and commitments. And, of course, he was right. (In that same decade Frank Sinatra’s manager encouraged Ol’ Blue Eyes to change his name to something “less ethnic.” He, too, declined the suggestion, though in a manner less polite than Bernstein.) While Bernstein’s life as an unlikely American icon recently graced the silver screen in Maestro, which was nominated by the Academy for a best picture award, his passion for Israel and connection to the country was just as significant.

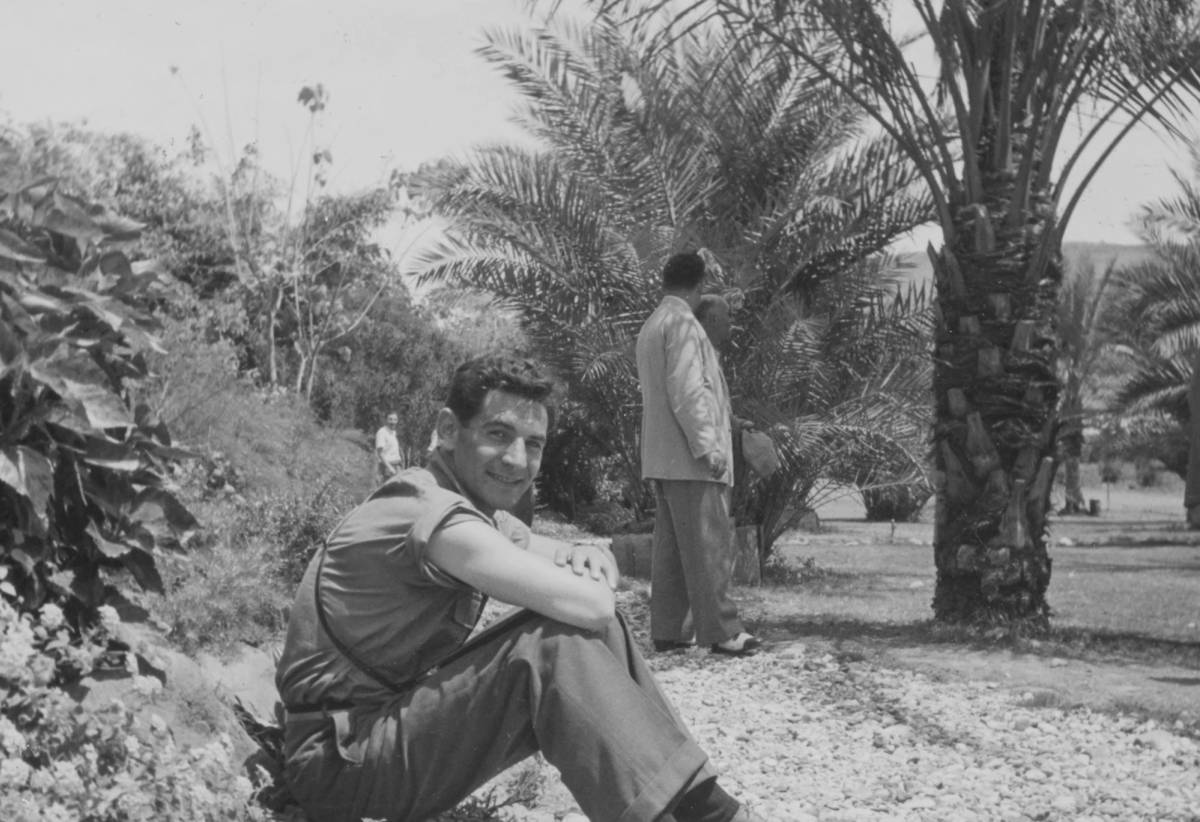

Leonard Bernstein at Ein Gev, 1947Library of Congress

His first trip to Palestine in 1947 was a great triumph for Bernstein. The Palestine Symphony Orchestra offered to make him its musical director, and for a few weeks, while conducting in Europe, he considered it. But Koussevitzky’s Boston Symphony Orchestra and its summer series in Tanglewood proved a greater attraction, and in the summer of 1947 Bernstein returned to the U.S. to conduct performances in New York and Boston.

From the U.S., Bernstein advanced his vision of a Jewish state through music—first and foremost by supporting the musical institutions already operating in British Mandate Palestine. The Palestine Symphony Orchestra was the most prestigious of these, formed by European Jewish refugees in 1936. When the Nazis evicted Jewish musicians from German orchestras, many went into exile; some emigrated to Palestine and joined the Jewish orchestra-in-formation. Arturo Toscanini, the most renowned conductor of his time, led the orchestra in its inaugural concert in 1937. A refugee from Italian fascism, Toscanini viewed the opportunity to conduct an orchestra of exiled Jewish musicians as the fulfillment of his duty to “fight for the cause of artists persecuted by the Nazis.” He was drawn to the Palestine Orchestra not only because of its musical excellence, the conductor asserted, but also because it was his “responsibility to humanity.”

One of the young people in the audience at that inaugural concert was Menachem Meir, the son of future Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir. He wrote in the early 1980s that he could still “retrieve the incredible excitement of the first Palestine Symphony concerts at which so many of the best musicians in the world gathered. The Jews of Palestine were starved for culture; many of them were highly educated, cultivated German and Austrian Jews who, flocking to Palestine during the early years of Hitler’s rise, had brought with them their taste for the sundry amenities of middle-class European life.” Bernstein was delighted to help carry on that European tradition, a tradition that now found refuge in the Jewish state

The British left Palestine on May 14, 1948. Eight hours later, in a crowded ceremony at the Tel Aviv Museum, David Ben-Gurion, declared the establishment of the State of Israel. At the end of the festivities the members of the Palestine Symphony Orchestra, now renamed the Israel Philharmonic, played “Hatikvah,” the anthem of the Zionist movement.

From the U.S., Bernstein advanced his vision of a Jewish state through music—first and foremost by supporting the musical institutions already operating in British Mandate Palestine.

In the 1948 War of Independence, the area around Beersheba, the main city of the Negev desert, served as a significant front. Israeli forces faced off against troops from Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and an expeditionary force from Iraq—all under the aegis of the Arab League. A few hundred poorly equipped Palestinian fighters, who had been skirmishing with Jewish and British forces since before the partition proposal, joined in. But the Arab League soon concluded that the Palestinian forces could not defeat the official Jewish army, the Haganah, and that it was therefore incumbent upon the League’s member states to send in their regular army forces. They did, but it still wasn’t enough. On Oct. 20, the Israelis defeated the Egyptian forces that had occupied Beersheba since mid-May.

It was against this dramatic background that Bernstein returned to Israel in late October of 1948. He performed in the same cities he had visited a year and a half earlier—Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, and Haifa—but now these cities belonged to the new State of Israel, and they were battlefronts in the Arab-Israeli war.

During this visit Bernstein wrote regularly to his father and sister, who had accompanied him on his earlier trip, recounting his experiences and even appending one letter with a postscript in Hebrew. In a letter from Tel Aviv to his close friend Richard Romney, Bernstein expressed his fierce attachment to Israel—and his antipathy toward her enemies. “This is such a beautiful experience that I can hardly write of it,” he wrote. “Truly I feel I never want to leave, despite all the tragedy and difficulty. I sit here in this charming city in a blackout, with the fucking Egyptians raising hell to the south, my beloved Jerusalem without water, and in siege. But the concerts go on—dozens of them—never one missed—with huge and cheering audiences—sometimes accompanied by shells and machine guns outside. And Haifa is certainly one of the fabulous beauty-spots on earth. Life is hectic, but pleasant beyond words: the orchestra is the most intelligent and responsive I’ve known; and I think I’ve fallen in love … This is a most miraculous people with a heroism and devotion I have never before seen. I visited the front in Jerusalem. I could weep with the inspiration of it. Everyone is young, inspired, beautiful in this new Army, and everyone is truly alive in this new State. So they slander and babble in Paris, but these people will never be drowned.”

Bernstein conducts the newly established Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, Beersheba, 1948Israel Government Press Office

After conducting performances in Israel’s three main cities, Bernstein embarked on a dangerous adventure: to perform for Israeli troops in the Negev, just three weeks after the battle of Beersheba. To organize that concert, he appealed to the patriotism of the musicians in the recently established Israel Philharmonic Orchestra. Bernstein did not envision a desert concert performed by the full 80-member orchestra; he was happy to find 35 musicians willing to make the dangerous bus journey from Tel Aviv. He also needed to arrange transport for a suitable piano, since he planned to perform three piano concertos—Mozart’s Concerto in B-Flat (K.450), Beethoven’s First Piano Concerto, and Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue—and conduct the orchestra from its bench.

For the men and women present at this electrifying performance, the concert provided a powerful emotional release, becoming for some the high point of a long and bloody war, in which 6,000 Israeli soldiers—1% of the state’s 600,000 Jewish inhabitants—died. News of the concert caught the attention of American readers. Time magazine’s article, “Mozart in the Desert,” reinforced the belief of many Americans that the Arab-Israeli war was a biblical drama being acted out in modern form; it described the I.P.O. musicians as having “crossed the Negev desert to give the battle-scarred Old Testament town of Beersheba the first symphony concert of its history.”

Soon after the performance began, Bernstein realized that the audience was quite familiar with the music he had selected. “I had thought I was bringing Mozart to the desert, but I found it there already,” he wrote. Opinions differ on exactly how many people attended the Beersheba concert. It wasn’t a sit-down affair—the musicians performed in a sandy, vacant lot—and estimates ranged from 1,000 to 5,000 soldiers (though this latter number seems unlikely). Time’s account described “1,000 soldiers who overflowed the benches, squatted in the sand, or sat on the flat roofs of the surrounding Arab houses.” With that concert, Bernstein became the first in a long line of American celebrities to entertain Israeli troops. Among them: Frank Sinatra in the 1960s, B.B. King and Leonard Cohen in the 1970s.

Bernstein captured the emotional impact of those concerts in a letter to Koussevitzky, then at rehearsals in Boston: “Which of all the glorious facts, faces, actions, ideals, beauties of scenery, nobilities of purpose shall I report? I am simply overcome with this land and its people. I have never so gloried in an army, in simple farmers, in a concert public.” The Israel concerts, he wrote, “are a marvelous success, the audience tremendous and cheering, the greatest being special concerts for soldiers. Never could you imagine so intelligent and cultured and music-loving an army.”

A few weeks later, Bernstein and the full I.P.O. performed in Jerusalem. On the program, at Bernstein’s insistence, was Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony. Its message was clear: Jewish life, destroyed in the Second World War, was now resurrected in Israel. To drive this point home, the audience was given Mahler’s text, translated into Hebrew.