How To Protect the Conversion Process

My friend was recorded in a mikveh by a rabbi. Let’s ensure the end of this abuse of power.

Almost all of the quiet moments I’ve had since Barry Freundel was sentenced to 6.5 years in jail for voyeurism have been spent thinking about my own conversion, the conversions of my friends, and the struggles we continue to face as gerim.

I converted in October 2007 while living in Brooklyn, NY. I had lots of questions during the process, which ultimately took a few years to complete. When I was learning, my mentor sometimes critiqued my clothing choices. I would ask, “is this normal?” or “should it be taking so long?” The answer I received was a resounding “yes,” as my friends and the rabbis I learned with told me that adhering to community standards of tzinus was part of the process to determine my sincerity.

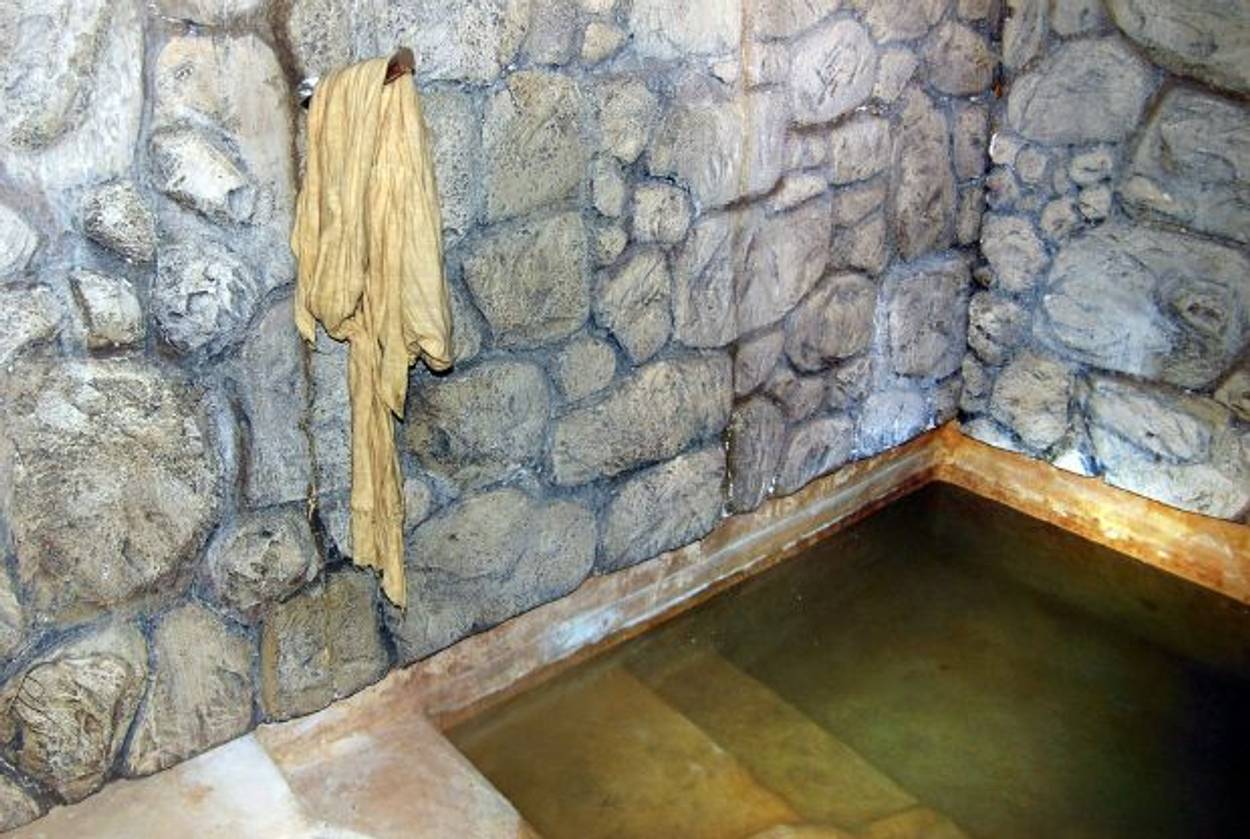

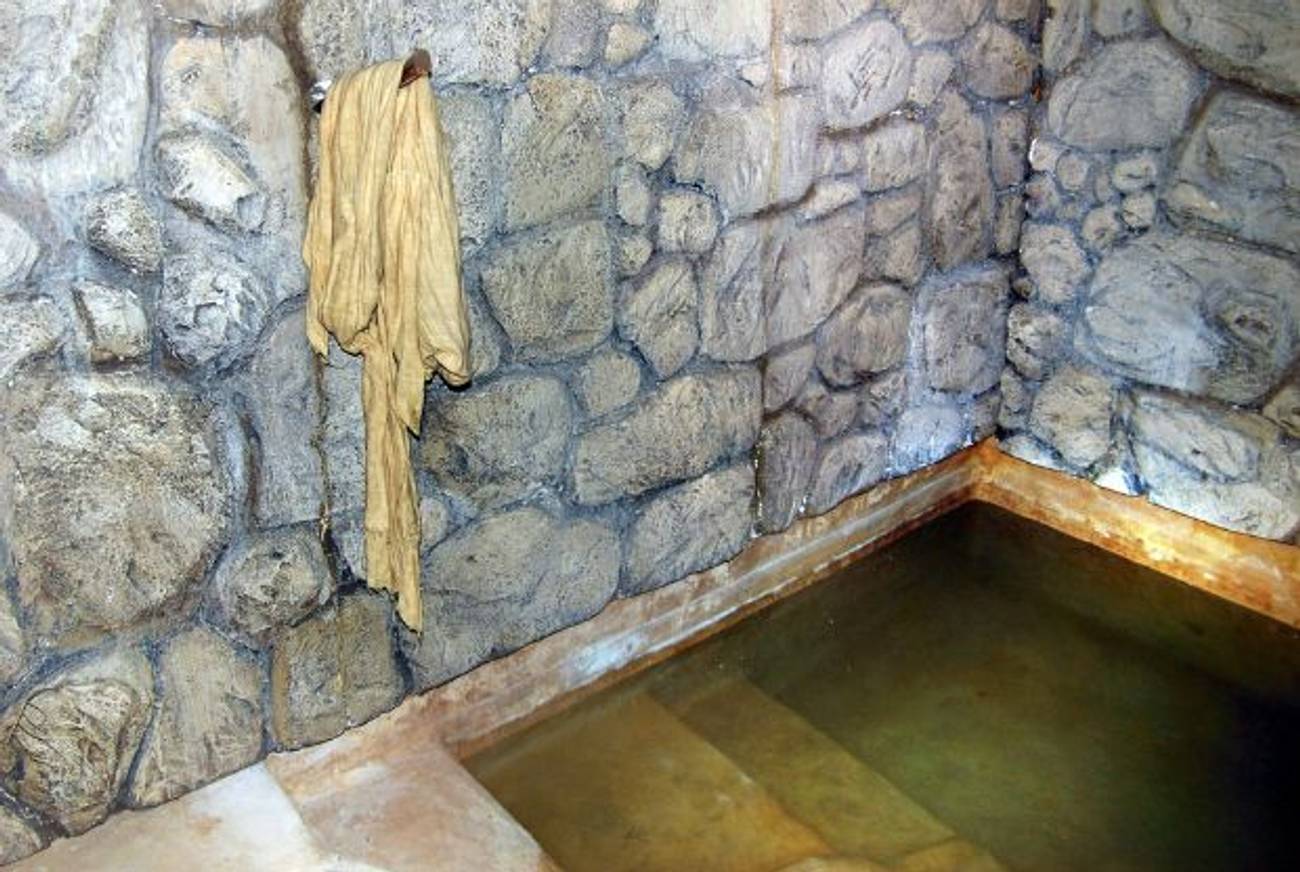

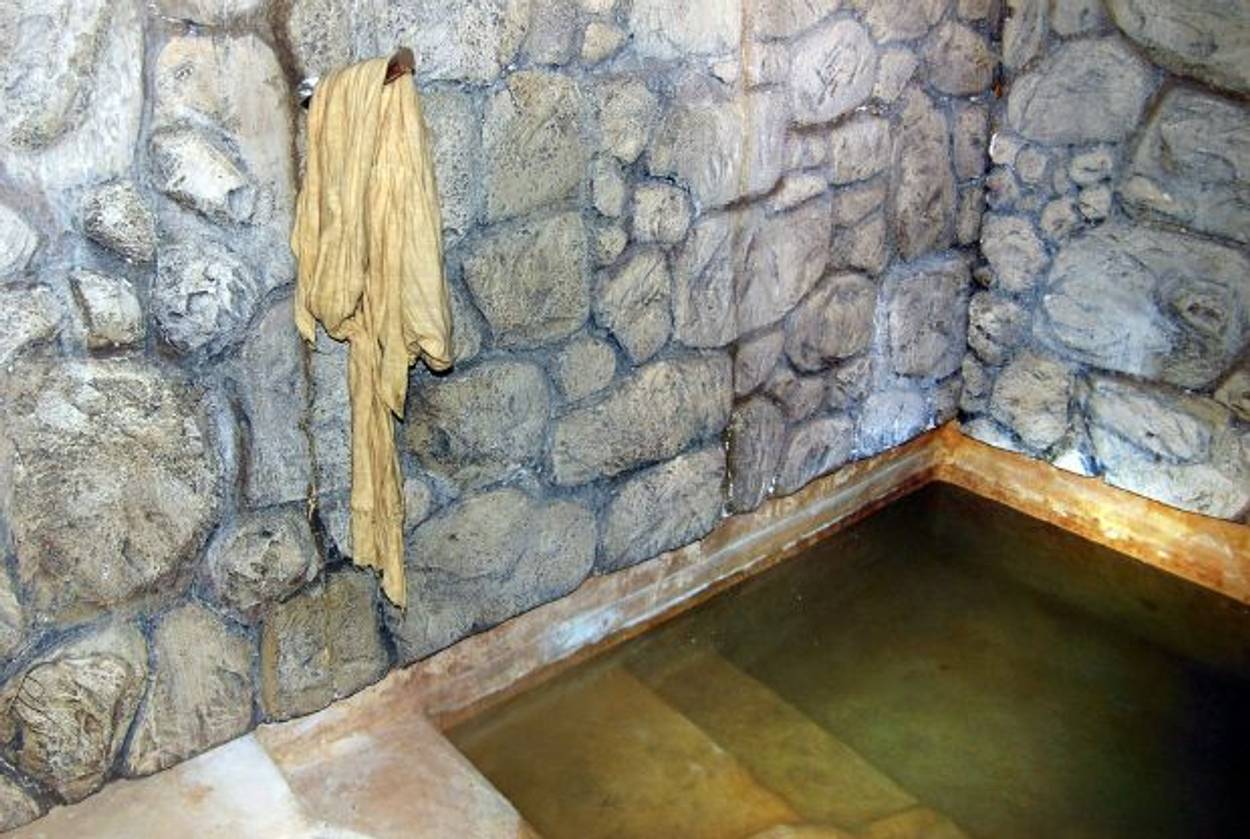

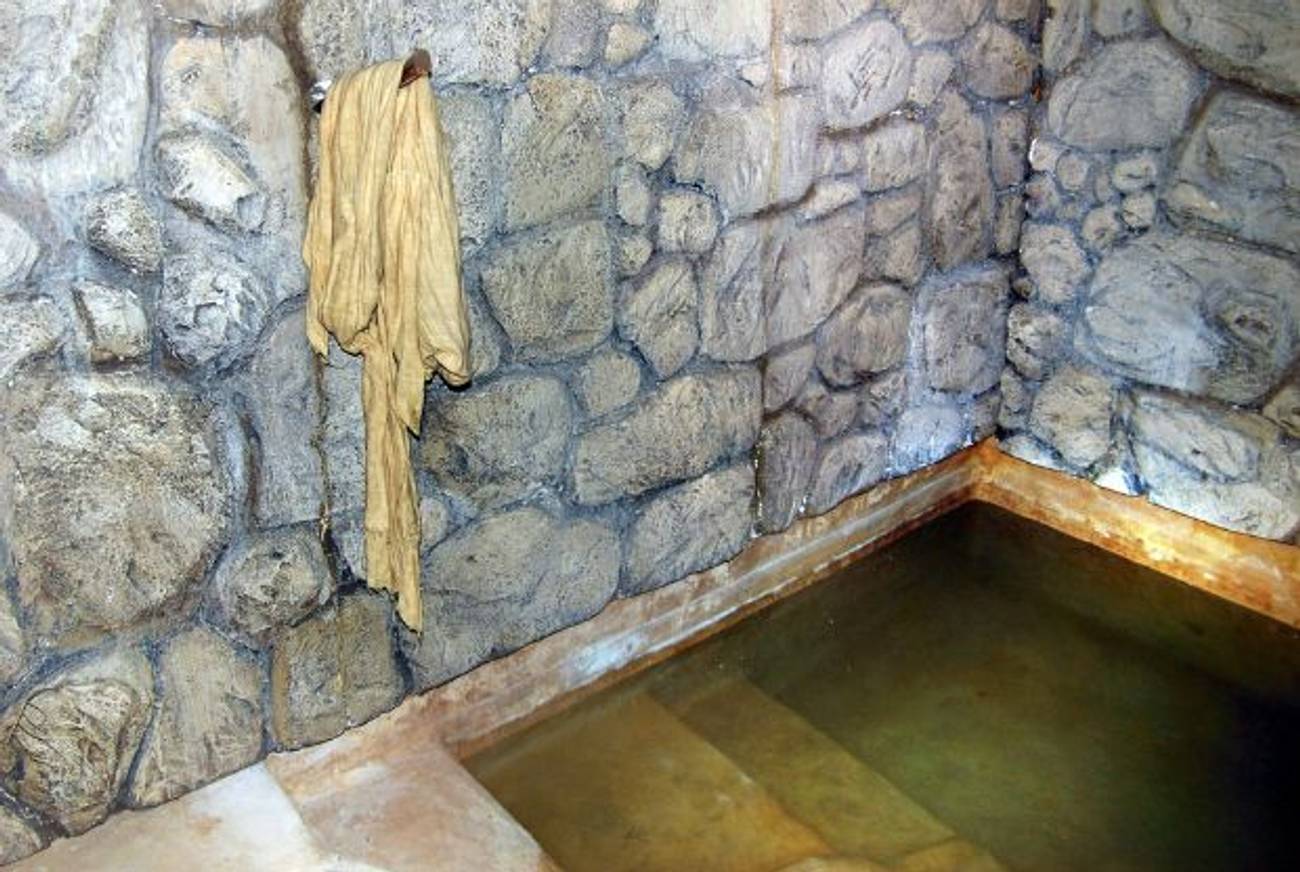

But the same was not true for one of my friends, a fellow convert who was filmed by Freundel inside his mikveh—the most private place for a Jewish woman outside of her own bedroom. She was taken advantage of by him during one of the most important and vulnerable times of her life.

When she received the news that she was was among the women filmed by Freundel, she started sobbing. The entire process from suspicion to trial and conviction has had far-reaching effects on her personal life, making her feel like she never wants to be part of any shul ever again. She feels mortified.

Though Freundel’s conviction offers some closure, to me it isn’t enough because the innate trust in our Jewish clergy that’s vital to a conversion has now been crushed. In fact, red flags were raised before Freundel’s crimes.

Here is what I would like to see change in order to protect the conversion process:

Establish an independent organization that provides converts with an ombudsman during the conversion process.

My victimized friend told me that something seemed “off” about the practice dunks during her conversion, and that her “Spidey sense was tingling.” But when she raised concerns about practice dunks to other candidates they all said that they had done them too, so she assumed it was part of the process, despite her feelings otherwise. It was a web of lies that was, in retrospect, impossible to be released from.

If only my friend could have asked a third party about the practice dunks, or other processes of conversion before, after or while they occurred. Doing so may have alerted the Rabbinical Council of America to investigate Freundel’s practices earlier.

Establish clear procedures for how to handle complaints received by the ombudsman from conversion candidates.

When a complaint is filed, the RCA (or other Rabbinic association or beis din) should immediately remove the rabbi from any public positions while accusations are investigated by an independent committee, or the law enforcement. In fact, the RCA investigated two complaints (in 2012 and in 2013) of prior misconduct by Freundel but did not inform his shul. As a result, Freundel was allowed to continue his rabbinic duties and work with conversion candidates. Why didn’t the RCA notify the shul? Why didn’t the RCA take immediate action to put a stop to potential misconduct while the investigation took place? Failing to suspend him during the investigation sends a confusing message indeed. In December 2014, Freundel was finally fired by the board of his shul, Kesher Israel.

Take away the title of “Rabbi” from those who are convicted sex offenders, and do not allow these individuals to squirm back into a position where they may have the opportunity to commit these crimes (or similarly disreputable ones) again.

Freundel is not the first rabbi to get caught.

In 2002, Yechiel Brauner, a rabbi and resident of Borough Park in Brooklyn, was convicted of felony aggravated sexual abuse in the first degree and misdemeanor sexual abuse in the third degree. His most recent arrest was in January 2014, not for violation of probation but for sexual assault. He was ultimately charged with forcible touching and sexual abuse of a young man (sexual contact without consent).

In 2009, Leib Tropper, rabbi and founder of the Eternal Jewish Family project, which advocates rigorous standards for conversion to Judaism, was caught on tape encouraging a conversion candidate to perform phone sex as well as soliciting her to have sex with his acquaintance, whom he refers to as “the Satmar guy.” Tropper was accused of demanding these sex acts in exchange for conversion papers. But in recent years, Tropper has built up his online presence as a character development expert for young adults, and has even lectured at the Yeshiva of Staten Island.

Lastly, consider Aryeh Goodman, a rabbi, who in 2013 was charged with allegedly molesting a child at a summer camp. Goodman still holds his position as director at East Brunswick Chabad, which includes an early childhood center.

Should any of these men be allowed to continue to call themselves a rabbi? Should any organization provide them with a platform to build back up their authority after their transgressions?

As a Jewish community we need to send a clear message to the vulnerable members of our tribe that they will be protected, and that no individual, not even a Rabbi, has the right to violate another person’s privacy. The parsha Vayikra tells us to judge others favorably, but I don’t forgive Barry Freundel because he shamed one of the strongest women I know. And now she’s left trying to find a comfortable safe place in a fraught Jewish world.

Previous: This Year, Let’s Celebrate #PurimNotPrejudice

Rabbi Freundel Fired Over Voyeurism Charges

Barry Freundel’s Meticulous Roguery

Freundel Sentenced to 6.5 Years in Jail

In addition to writing for JN Magazine, Tzipi also works as a birth and postpartum doula. She currently lives in New Jersey with her husband and daughter.