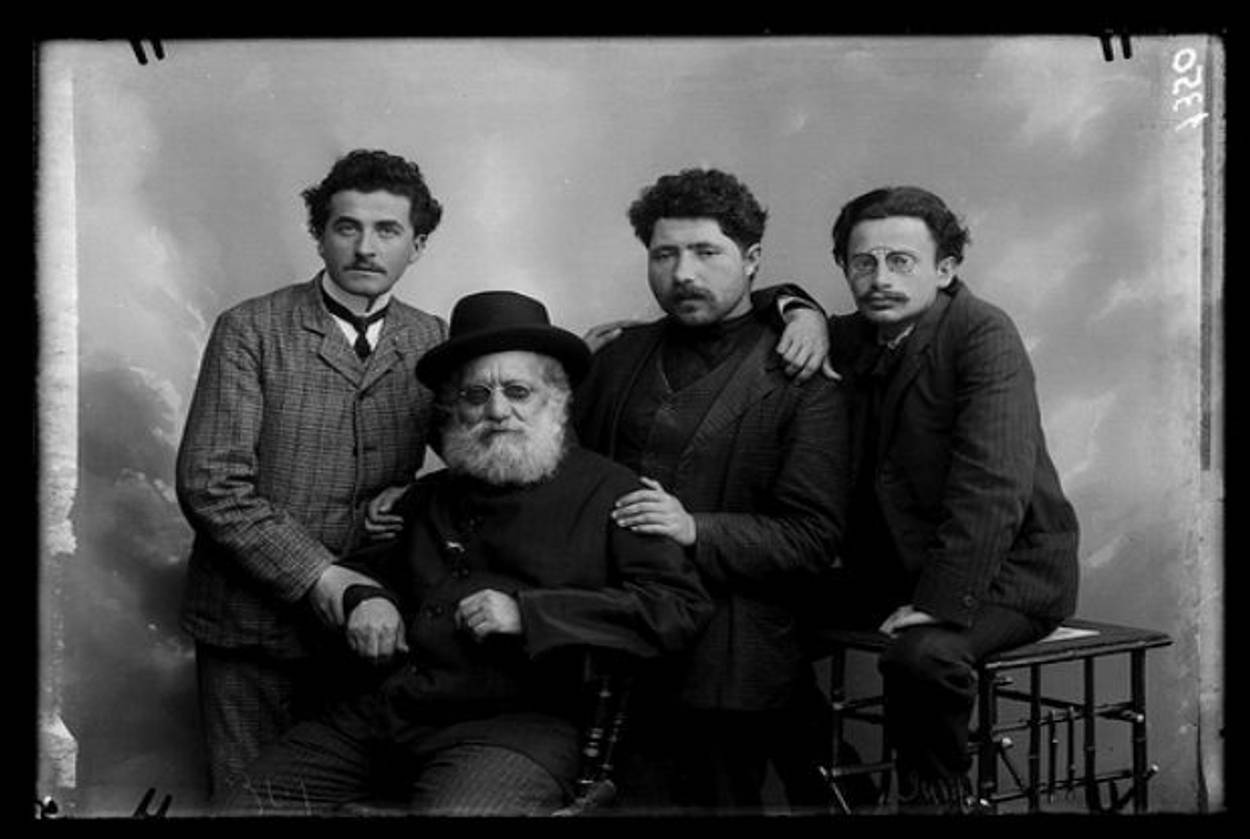

S.Y. Agnon’s ‘To the Galilee’: An Introduction

The short story, a Lag BaOmer tale, appears in Tablet for the first time in English translation

In 1977, seven years after S.Y. Agnon’s death, his daughter, Emunah Yaron, published To the Galilee in Hebrew as “HaGalilah,” in a collection entitled Pithei Devarim. (In fact, at one point toward the story’s end, we discover that the entire story is being told to the narrator’s daughter.) The manuscript seems to have been a fragment from a larger work undertaken in the mid-1950s called “HaDom vehaKisse” (“The Footstool and the Throne,” as yet untranslated), which mixes elements of memoir and fiction.

To the Galilee, appearing in Tablet for the first time in English translation, is an anecdotal travel narrative that describes the youthful journeys of the novice author through the Land of Israel at the height of the Second Aliya (the period prior to World War I). What the tale lacks in plot, it makes up for by preserving the charm and rhythms of pastoral Palestine during that time period. To the Galilee is also a testament to the adoration and nostalgia that Agnon and his generation felt for the pioneering spirit of those times, despite their many struggles and deprivations. It is, as well, a record of the Jewish world in transition, between traditionalism and new secularism, and between Europe and the Land of Israel.

Three years after arriving in Jaffa from his ancestral Galicia, Agnon made a tour of the settlements and towns in 1911, reaching Meron in the Galilee to celebrate Lag BaOmer, as described in the story. He was spared from harm when a building collapsed at the tomb of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, which killed 11 people and injured dozens more during Lag BaOmer. The incident was woven into the tapestry of Agnon’s personal biography and self-made myth about Lag BaOmer in his life.

Among the other things he claimed took place in his life on Lag BaOmer: the writing of what became his first published work (1904); the arrival of the ship that brought him to Jaffa from Europe (1908); and his marriage to Esther Marx (1920). Agnon also claimed that the writing of various books were either completed or initiated on Lag BaOmer, along with receiving a variety of good tidings over the years on this day. And even though we know some of these claims to be historically inaccurate, what’s significant is the way he crafted a myth about himself, drawing cords of memory between the man that would become Agnon—almost a character out of one of his own books—and Lag BaOmer, perhaps the most mystically fraught day in the Jewish calendar.

Previous: S.Y. Agnon Turns 125

Related: Twofold

What Happens When Agnon and Appelfeld Speak Like Faulkner and Hemingway?

‘On the Edge of Our City’: A Short Story for Yom Kippur by Aharon Appelfeld

Rabbi Jeffrey Saks is the founding director of ATID and its WebYeshiva.org program, and is the Director of Research at the Agnon House in Jerusalem. Some of his translations of Agnon’s stories have appeared in Tablet and in the Toby Press’ Agnon Library.