I confess to having been surprised by the lavish coverage of his death last Friday, by the sight of his picture on the front page of my New York Times when I left home in the morning, on the front page of the New York Post when I passed the newsstands in the airport, and then on the front page of the Los Angeles Times when I landed in L.A. that afternoon for the funeral.

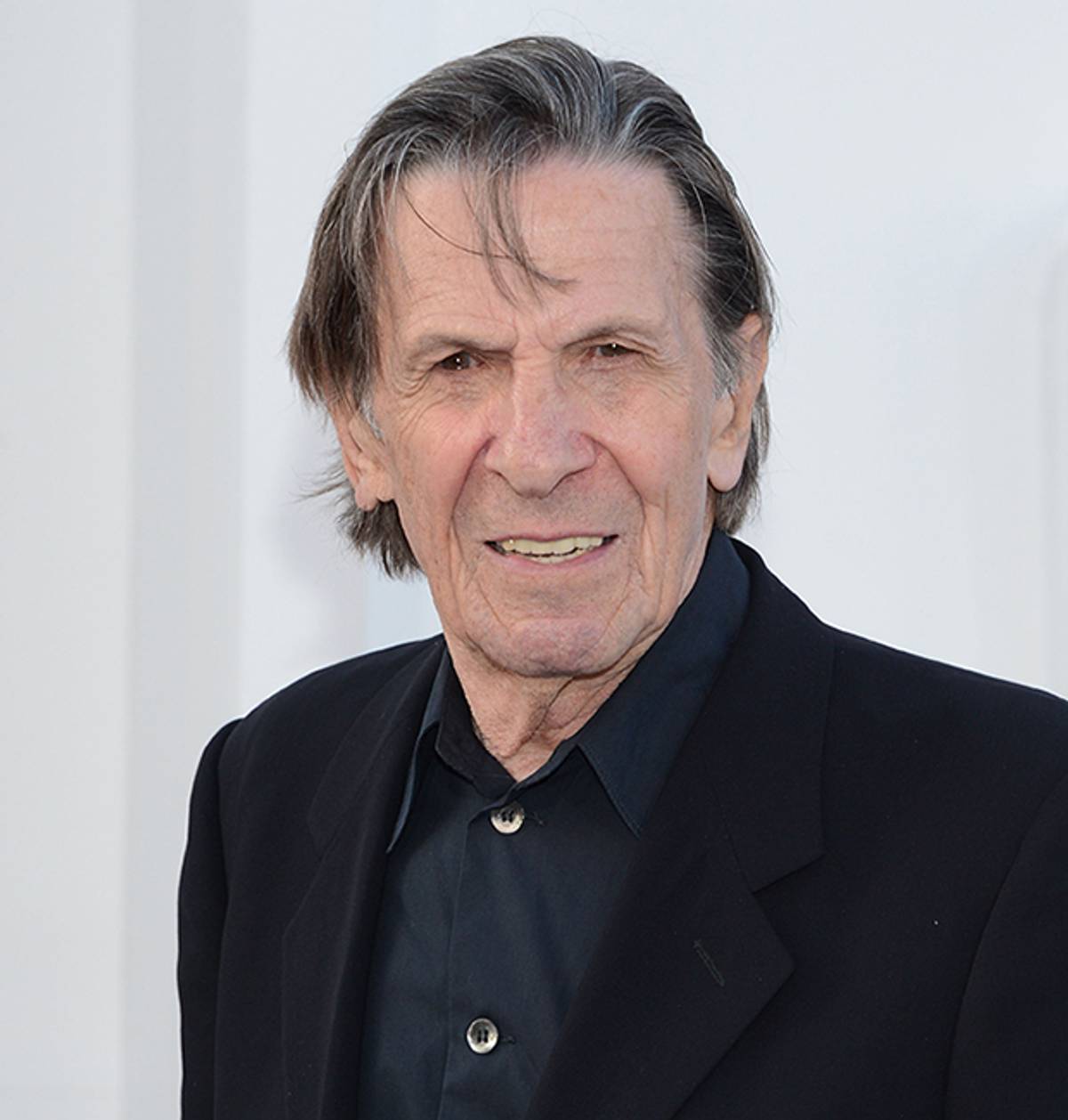

The international outpouring of love and appreciation for Leonard Nimoy has been nothing short of astonishing—from the tsunami of tweeting fans to the poignant “I loved Spock” from the Oval Office.

Frankly, I had forgotten who Leonard was to the world. To me, he was not Spock (I confess to never having seen an episode of Star Trek); he was SuperMensch, a great but humble man, a dear friend with a wise old Jewish soul.

We met in 1991 after his wife, Susan, then a film producer, expressed interest in optioning my book, Deborah, Golda, and Me, and came to New York from L.A. for a meeting at my apartment. Though she never did buy the book rights, our friendship and that of our husbands was launched that day. In the 25 years since, we’ve shared innumerable anniversary dinners, birthday toasts, and Shabbat meals, a makeshift mikvah in the Mediterranean, magical vacations, stayed at each other’s homes, celebrated each other’s simchas, and lived through each other’s tsuris.

To the many appreciations you’ve undoubtedly read over the last few days, I’d like to add a few snapshots from my album—intimate glimpses of the character the world knew as half-Vulcan but I knew as all human.

“Leonard’s Hebrew name was Yehudah Lev, meaning ‘a Jew with a heart,’” said Rabbi John Rosove at the funeral. The name described the man.

In a roomful of talkers, Leonard was the one who listened. He paid attention, pondered your opinion with a flatteringly serious intensity, and only spoke when he had something to say. Unlike most famous folks, his contributions were rarely self-referential. If you asked him point-blank about himself or his career, however, he would answer with a story, a masterfully-told story, that breathed tension, drama, or self-deprecating humor into his always-relevant, never self-serving replies.

Unless required by propriety to dress up for something, Leonard was the embodiment of the casual Californian. But he was unselfconsciously elegant, never fancy or showy, his style and substance of a piece. I will always see him in a baseball cap, loafers with no socks, and soft crew neck sweaters with only a white T-shirt underneath.

Leonard was comfortable with silence. He loved to sit in the sun, gaze out at the water, or close his eyes and think. When he and Susan stayed at our country house in the Berkshires, I would marvel at his capacity for serenity and stillness; even in a rocking chair, he wouldn’t move, staring at the lake from under the brim of his baseball cap and radiating contentment.

When things got hectic around his house, he would quietly excuse himself and go to his studio to write or work on his photography, or disappear into his and Susan’s bedroom to read, think, or nap.

His appetites were modest. A recovering alcoholic with decades of abstention under his belt, his fuel was juice or soda. For breakfast, he liked peanut butter on a banana. His favorite foods were steak, ice cream, and chocolate. For one of his birthdays, my husband Bert and I arranged for quarterly deliveries of a variety of different steaks, and as he ate his way through them, he emailed us his ratings.

At dinner parties, Leonard was the man who reached for his wife’s hand between courses and held it on his knee under the table. I’ve seen him kiss his grown son, Adam, as well as his daughter, Julie, in public. I remember marveling years ago at Leonard’s effortless teddy bear snuggle when his stepson, Aaron, Susan’s boy, then a tall, gangly teenager, was given to folding himself into Leonard’s lap and resting his head on his stepdad’s chest.

My friend’s old Jewish soul fluttered into view whenever he joyfully spewed a geyser of mamaloshen, a Yiddish punch line, or one of his grandmother’s Yiddish proverbs. The old soul took a bow when Leonard described how the Vulcan salute came straight from the priestly blessing he witnessed in his childhood shul when he secretly peeked out from under his grandfather’s tallit despite warnings not to look at the Kohanim’s holy ritual. It shined when we talked about the feminist aspects of his art photography book, Shekhina—beautiful pictures of nude women, their arms encircled by straps of tefillin, their nakedness draped by a filmy tallit or marked with the Hebrew letter shin. His intention was to illuminate the intersection of sensuality and spirituality and to honor the female personification of God. He was stung when the Seattle Jewish Federation refused to allow him to show slides of his photographs, puzzled that anyone could fail to perceive the transcendent embodied in the female form.

Despite his supposed ambivalence about Spock as his alter ego, I’ve always felt Leonard knew exactly who he was and never wanted to be someone else. It was as if he’d been on this earth before, tried out multiple identities, and finally settled on his own. While actively curious about other people’s views on art, literature, and politics, he answered to no one but his conscience and held firm to his own beliefs.

In 2011, I asked him to sign a fundraising appeal on behalf of Americans for Peace Now, an organization I’ve cared deeply about for more than 30 years. APN actively promotes a two-state solution—a secure, democratic Israel alongside a secure, independent Palestinian state—an idea that has become controversial in parts of the Jewish community.

When I’ve asked other celebrities to sign a petition, ad, or call to action—whether about peace or women’s issues—they usually want to know who else is signing; they need cover; they need time to consult their friends, managers, or agents to be sure they’re not risking their public image. Not Leonard. He simply read the suggested draft, tweaked a few sentences, then put his name to the letter, which closed with a plea for a tax-deductible contribution to APN and the inside joke, “Dare I say it? It’s the logical thing to do.”

Leonard was pleased when I told him his letter was the single most successful fundraising appeal in APN’s nearly 40-year history. After he died on Friday, the organization reposted his letter and it garnered the greatest number of comments ever recorded on APN’s website.

To say that Leonard was generous is like saying Spock was logical. Generosity was his essence. With Susan as his eyes, ears, and vetting expert, he supported many a worthy project, not just with his money but often with his name, burnishing the enterprise with the patina of his inherent trustworthiness. One such project, the Leonard Nimoy Thalia in New York, a favorite Upper West Side venue, will always have special meaning to me because Leonard and Susan once gave me a book party there, making me appear far more important than I was by providing his theater for my talk and its on-site restaurant for a catered after-party.

Our vacations with the Nimoys have been magical excursions on land or sea, days of relaxation or exploration capped by evenings of orchestrated birthday festivities, organized book discussions, or, best of all, Leonard’s readings for our small group of fellow travelers. In his unmistakably sonorous voice, he read aloud from “Gimpel the Fool” by Isaac Bashevis Singer and short stories by Woody Allen, that, consummate pro that he was, he’d have spent hours in the afternoon preparing. You’d have thought he was about to perform for a demanding Broadway audience rather than six or eight friends who’d had a couple glasses of wine.

The day after celebrating his 80th birthday at his Los Angeles home, we went to the Getty Museum to hear Leonard read in the “Selected Shorts” series established years before by his friend and fellow Yiddish lover, Isaiah Sheffer. That day, Leonard’s selection was “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love,” by Raymond Carver, an alcohol-soaked exchange between two couples grappling with memories of love, hate, violence, and loss. Its themes seemed to have a special resonance for Leonard, the long-recovered alcoholic who often said that Susan’s love saved his life.

Another literary work that he treasured was “Desiderata,” the 1927 poem by Max Ehrmann, which, among other things counsels, “be yourself,” “be on good terms with all persons,” and “be careful, and strive to be happy”—prescriptive lines as emblematic of Leonard as his iconic, ‘Live long and prosper.” (You can hear him recite Ehrmann’s poem on YouTube.)

Leonard once told me the most memorable, meaningful role of his life was Ralphie in Clifford Odets’ Awake and Sing, a part he originally played in an amateur production when he was 17 years old. The play spoke to him, he said, because it so closely mirrored the family dynamics, left-wing politics, and conventional aspirations of his parents and the tenor of the household in Boston’s West End where he grew up.

Actor, director, writer, poet, singer, sailor, pilot, art photographer, Leonard has deservedly been called a Renaissance Man. Yet he never seemed unduly impressed with his accomplishments. And he never took his talents for granted. I remember two occasions when I glimpsed in him an almost boyish nervousness and heard the sort of self-effacing disclaimers people mutter as a hedge against humiliation.

The first instance was in the summer of 2010, just before the opening at Mass MoCA (Museum of Contemporary Art in Massachusetts) of an exhibit of his “Secret Selves” photographs—pictures of ordinary people revealing their hidden or repressed selves. Leonard was clearly worried about the series’ critical reception and overjoyed when it won high praise. The second occasion was just a few months ago, when my husband and I sat with him and Susan at Sotheby’s waiting for one of his photographs to come up for auction and Leonard shyly confessed that he feared no one would bid on it. (It sold, and for a nice price.)

This unique combination of confidence and humility, vibrancy and serenity, haimish warmth and cosmic cool is something I’ve never encountered in anyone before and probably never will again.

At his funeral on Sunday, the front page obits were forgotten. There were no statements by boldface names. When it counted, and in the presence of his adored wife, Leonard was remembered by those who loved him best—his two children, his stepson, five of his six grandchildren, his brother, his long-time rabbi, and one of his close friends.

Rabbi Rosove concluded the eulogies with these lines from poet Raymond Carver:

And did you get what you wanted from this life, even so?

I did.

And what did you want?

To call myself beloved,

To feel myself beloved on the earth.

Leonard was beloved on the earth—and quite possibly on distant planets. May his memory be for a blessing.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin is a founding editor of Ms. magazine and the author of 11 books.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this piece misattributed the poem read at the service.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin, a founding editor of Ms magazine, is a writer, lecturer, and social justice activist.