Helen Mirren’s New Nazi Art Movie

In The Woman in Gold, Mirren takes on Austria for her family’s artwork

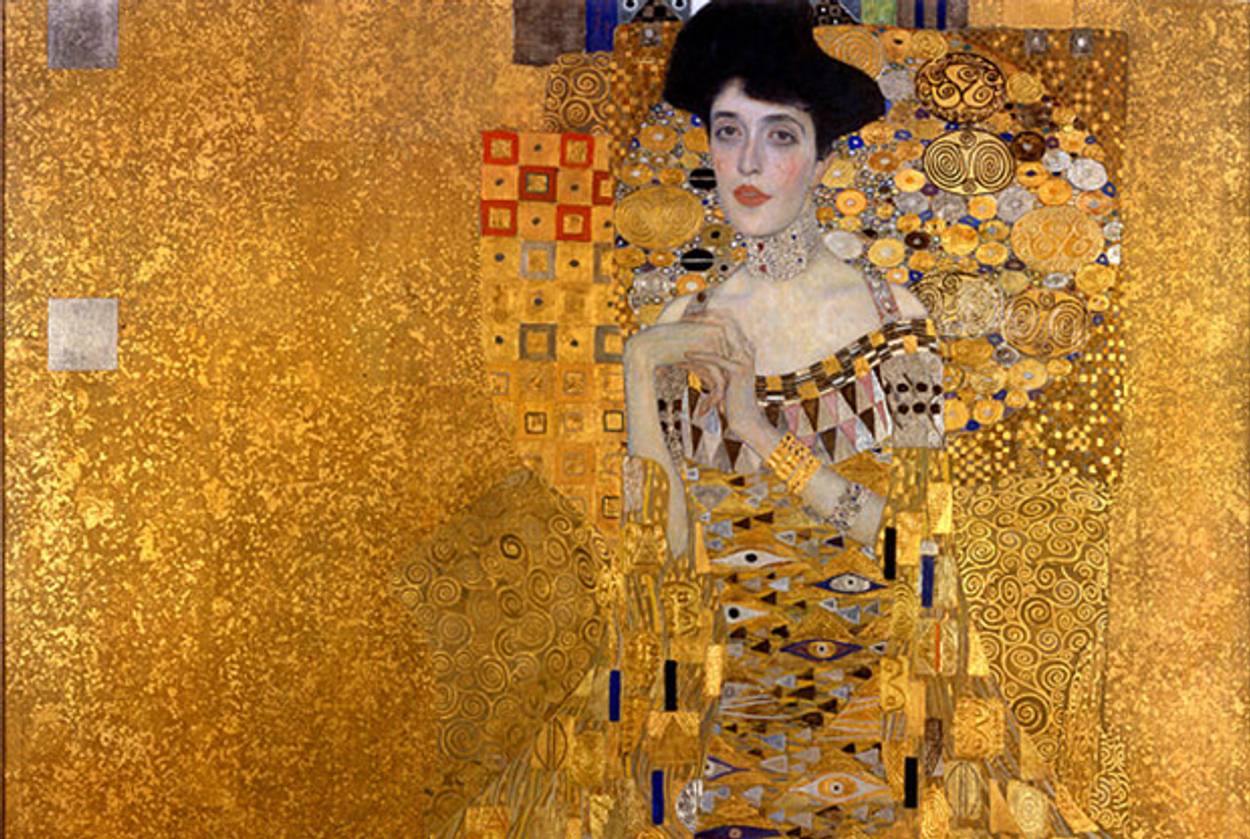

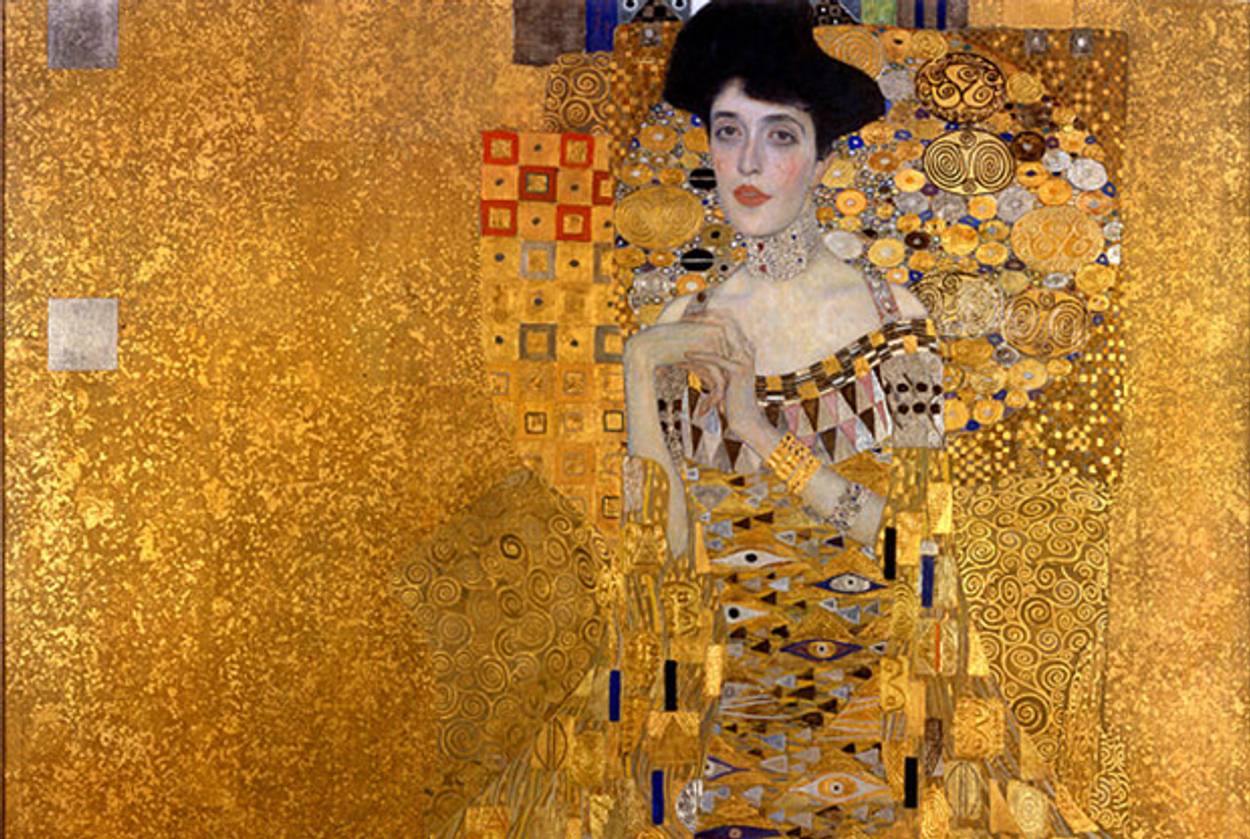

Move over, Monuments Men. The newest movie about the quest to recover Nazi-looted art after the Holocaust is The Woman in Gold, which is based on the fascinating true story of Maria Altmann, an Austrian Holocaust survivor who battled the state of Austria for famed painter Gustav Klimt’s perhaps even more famed portrait of her aunt, Adele Bloch-Bauer. The portrait, explains Altmann, played by a nearly unrecognizable Helen Mirren, had been stolen off the wall of their home by the Nazis and currently hung in the Belvedere in Vienna. She enlists the help of a charming lawyer (Ryan Reynolds) to help get her family’s masterpiece back from the Austrian government, who claims it as their own.

The film is based on Anne-Marie O’Connor’s 2012 book, The Lady in Gold: The Extraordinary Tale of Gustav Klimt’s Masterpiece, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer (or at least it’s based on part of it; the Klimt restitution case comprises just one third of the lengthy historical book).

I won’t spoil the ending, but the painting now hangs at the Neue Galerie New York. (There’s also a fine art-inspired Barbie made in Bloch-Bauer’s likeness.)

The Woman in Gold looks like a great movie—and will likely garner comparisons to The Monuments Men, the similarly focused film that came out earlier this year. But what’s more astonishing, though, is that two star-studded films about the recovery and restitution of Nazi-looted art will have been released within about a year. The premise of such films is understandably appealing: there’s drama, intrigue, and it’s all based on true events (for what that’s worth). There are the clear good guys and bad guys, but there’s also the grey-area evil—those who stood by in silence, who perhaps profited inadvertently, who loudly claim paintings that didn’t always belong to them.

That murky dynamic exists in real life as well, as Jewish heirs to famous paintings by artists like Matisse continue to fight for their own property back. While there have been recent breakthroughs of sorts in such restitution, it’s the kind of story that typically plays out better on the big screen.

Previous: Germany Orders Nazi-Looted Painting Returned to Jewish Heirs

Germany Rules Matisse Belongs to Jewish Heirs

Related: Why the Germans Haven’t Returned $1 Billion Worth of Nazi-Looted Paintings

Stephanie Butnick is chief strategy officer of Tablet Magazine, co-founder of Tablet Studios, and a host of the Unorthodox podcast.