The Ecstasy of Rage

In an excerpt from ‘Memoirs of a Jewish Extremist,’ the activist remembers Meir Kahane and the JDL

The arrests in Russia began in June 1970. A brief report on the radio said that twelve Jews had been seized at the Leningrad airport while attempting to hijack a plane to Israel. Glenn Richter called: “Comrade Kleinski? Bad news for the Jews.”

Glenn said the hijacking was probably a frame-up. But what if it wasn’t? What if some Jews had become so desperate that they were ready to force their way out of Russia? If the hijacking were real, then Soviet Jews had moved from letter-writing to violence. And our peaceful, “responsible” demonstrations would no longer be enough.

An SSSJ all-night vigil at the “Isaiah Wall”—a small plaza opposite the UN, on whose wall was engraved Isaiah’s messianic prophesy of a world without war—drew less than fifty people. No reporters came. I called a radio news station for the third time and said, “If you want us to smash windows, we’ll smash windows.” Twenty minutes later, a reporter appeared. “Who’s the window-smasher?” he asked.

We sat on the winding steps leading down into the Isaiah Wall plaza and spent the night debating our next move. We were convinced that the hijacking arrests were just the beginning of a KGB campaign to destroy the Zionist underground and that anything was possible now—pogroms, even mass deportations.

We needed a hundred thousand people in the streets immediately. But only the Jewish establishment had the power to summon a real protest movement; and its single response to the Leningrad arrests was a press release, deploring and denouncing. Instead of rallying outside the UN, I said, we should be taking over the offices of B’nai B’rith and Hadassah.

The next morning we left the Isaiah Wall and walked to the nearby headquarters of B’nai B’rith’s Anti-Defamation League (ADL). We laid our torches, stinking of gasoline, around the lobby. “We demand a meeting with ADL leaders,” I said to the receptionist.

Policemen entered the building. Glenn began photographing. The cops left.

We were invited to a conference room. We sat opposite a half-dozen ADL officials at a long table. Disheveled and sleepless, our very appearance proclaimed a state of emergency.

“We do more for Soviet Jewry than anyone,” began a man who called himself ADL’s foreign affairs expert. “We gave two thousand dollars last year to the American Jewish Conference on Soviet Jewry.”

“Out of your budget of how many millions?” asked an SSSJ activist named Noam.

“Of course we can never do enough for our brethren in Russia.”

Noam rolled his eyes.

“You kids don’t know what you want,” the foreign affairs expert said.

“We want you to buy a full-page ad in the Times about the Leningrad arrests,” I replied.

“The Soviet Union could financially ruin us by arresting twelve Jews a week,” said the expert, laughing.

“Ha, ha,” said Noam.

“I don’t understand this concern for twelve Jews when there are three million in the Soviet Union.”

“What about when the number was six million?” I asked.

“Yes, we lost the battle for the Six Million.”

“You didn’t lose the battle,” I said. “You never fought it.”

“What are you doing for Boris Kochubiyevsky?” demanded Noam.

“We have information,” said the foreign policy expert, “that Kochubiyevsky is doomed.”

“He’s doomed,” said Noam, “because of people like you.”

***

The only real response to the Leningrad arrests came from the JDL. Meir Kahane led twenty followers into the Soviet trade office in Manhattan, waving lead pipes and physically expelling its staff. Unlike our peaceful SSSJ vigil, the takeover made headlines.

The JDL had entered the Soviet Jewry struggle. Its members chained themselves to the wheels of an Aeroflot plane on a Kennedy Airport runway and toppled police barricades at the Soviet UN mission. They disrupted appearances by visiting Soviet artists, releasing mice during a violin concert, rolling marbles onto an ice-skating performance, dancing a hora onstage during a ballet recital. Kahane had expropriated the tactics of the radical Yippies, the violent pranksters of the New Left, orchestrating acts of rage for the TV cameras.

In one sense Kahane’s strategy resembled Ya’akov Birnbaum’s: The JDL was trying to free Soviet Jewry by threatening Soviet-American relations, making it more worthwhile for the Kremlin to release its Jews than hold them. But Ya’akov believed in an incremental campaign of education and peaceful protest, mobilizing American Jewry and sympathetic non-Jews; whereas Kahane launched a campaign of terror against Soviet-American relations—guerilla war, or at least violent guerilla theater.

Kahane despised SSSJ’s faith in gentile decency. Instead of cultivating public opinion, the JDL deliberately flouted it, playing Black Panthers to SSSJ’s Freedom Riders. Kahane didn’t care if the New York Times condemned JDL violence or if ballet aficionados booed JDL disrupters. What mattered was getting noticed. Kahane understood the demonic side of media: The uglier you behave, the more coverage you receive.

Politicians invited to SSSJ rallies were almost always liberals, speaking the rhetoric of civil rights; we shunned cold warriors, whose anticommunism would allow the Kremlin to dismiss us as politically motivated. But Kahane brought far-right congressmen to JDL rallies and joined with Eastern European anticommunist exiles whom he despised as closet Nazis. Where Ya’akov envisioned a messianic coalition of goodwill, Kahane preached a coalition of cynicism. The Jews, wrote Kahane, have no friends, at best temporary allies of convenience.

Ya’akov bitterly resented him. “I know Meir, heh, heh,” Ya’akov said to me, with an insinuating, nasty laugh. “He came to a few of our rallies in the beginning, made a speech or two, very passionate and all the rest of it. But no substance, you see. He’s ruining years of our work with wild acts of self-aggwandizement. Meir is a violent soul; he dweams of chasms of blood.”

How would we free Soviet Jewry: by alliances of expedience, or by those of goodwill? By violent acts that won publicity for our neglected cause, or by patient coalition-building that cultivated rather than alienated potential supporters?

I trusted Ya’akov. And I mistrusted Kahane as an opportunist, using Soviet Jewry to get headlines for himself and his group. And the JDL could be so embarrassing: One TV news report about a JDL riot at the Soviet mission focused on a hysterical woman with glasses shaped like slanted eyes repeatedly shrieking, “Jewish blood! Jewish blood in the streets of New York!”

And yet I envied the JDL’s audacity, its ability to manipulate the media. The JDL was bringing a new level of desperation into the Soviet Jewry movement, transforming it into a “real” cause for which protesters went to jail. I’d always prided myself on being at the center of the movement; but now I felt that center shifting, from SSSJ to the JDL. Suddenly there were people whose names I didn’t even know who were sacrificing more for Soviet Jewry than I was. How could I miss the intensity?

***

A pipe bomb exploded outside the Manhattan office of Aeroflot, the Soviet airline. Someone phoned the media and said, “So long as Jews are on trial in Russia, Russia will be on trial before the world. Never again.” Suddenly the Soviet Jewry movement—that most gentle of protest movements—had its own terrorists.

A few hours later Meir Kahane appeared at a crowded press conference, which he’d just happened to schedule a week earlier for this very time. Reporters asked whether the coincidence didn’t prove he’d known of the bombing in advance. Kahane smiled. “We take no responsibility,” he said. “But we applaud the act.”

I was thrilled. No one could dismiss us now. We were just like the anti-Vietnam movement: serious. Thanks to the bombing, the Leningrad trial had finally become front-page news. I refused to speculate about what might have happened had passersby been in the area during the explosion. Instead, I fantasized about placing a bomb outside a Soviet office, then slipping home and turning on the radio, waiting for the news.

I called Moish to share my excitement. I told him that I blamed the establishment Jewish leaders for the bombing. If they’d done their job and organized big peaceful rallies, no one would feel desperate enough to blow up Soviet offices. Moish was bemused. “Still busy with the establishment, Yossel? Forget the establishment, Yossel. A dozen ‘Exodus’ marches won’t do as much as one meshuggener with a bomb.”

***

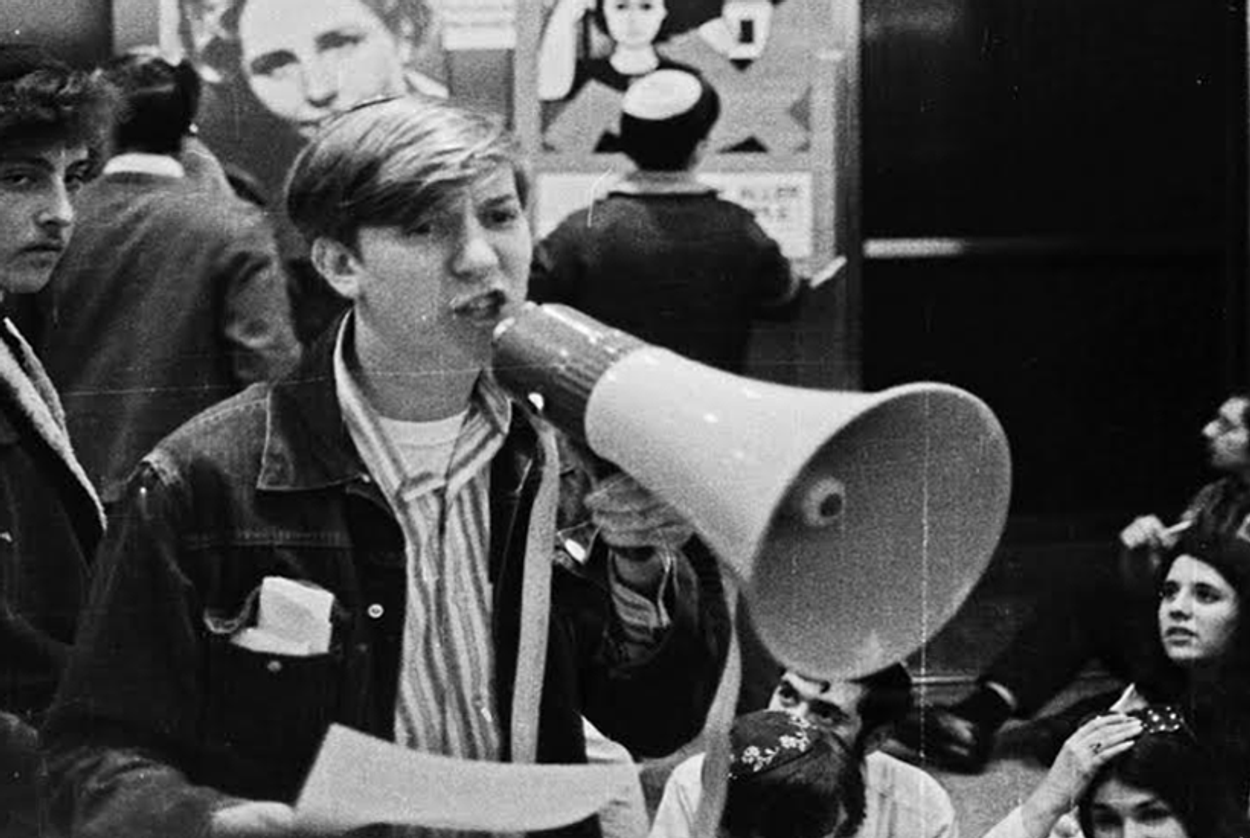

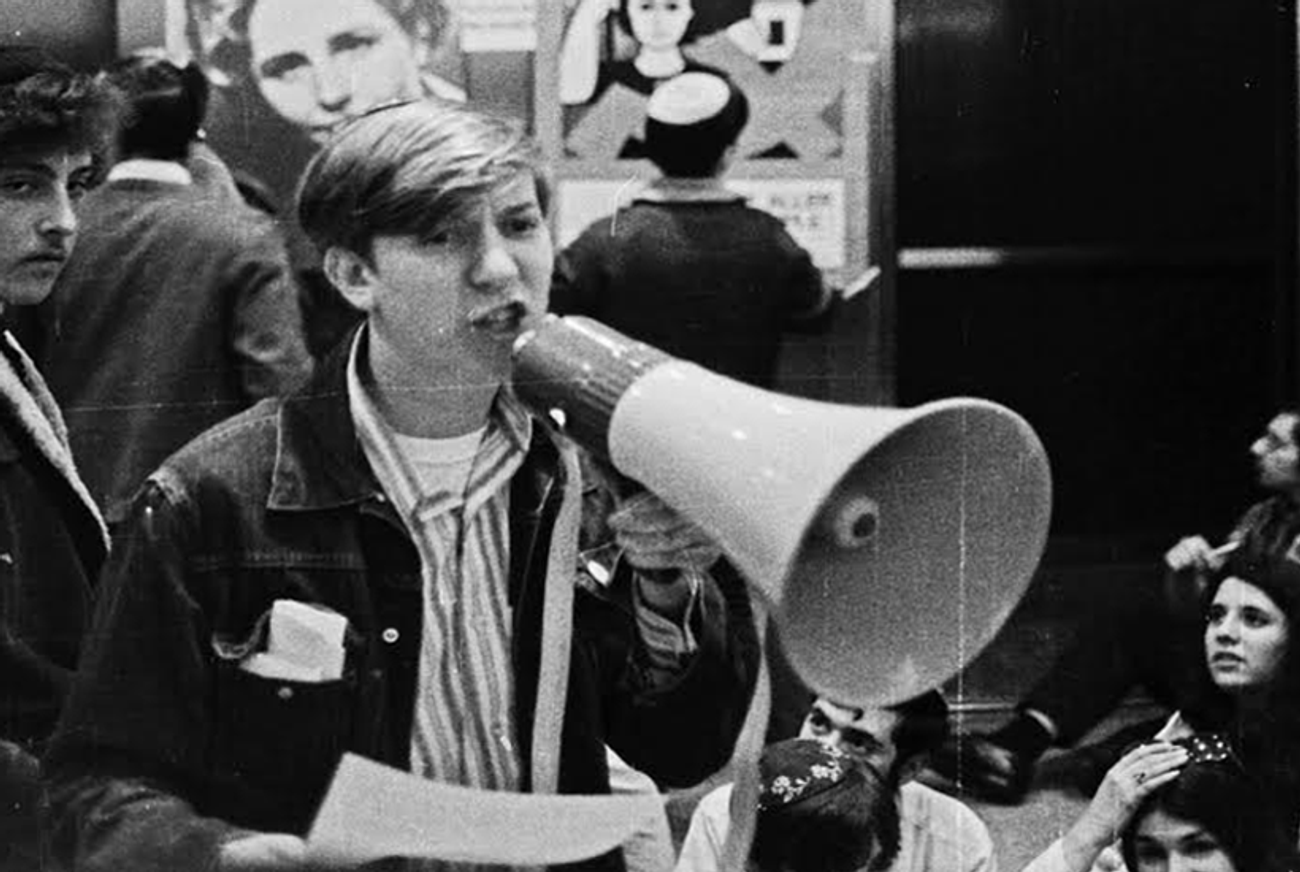

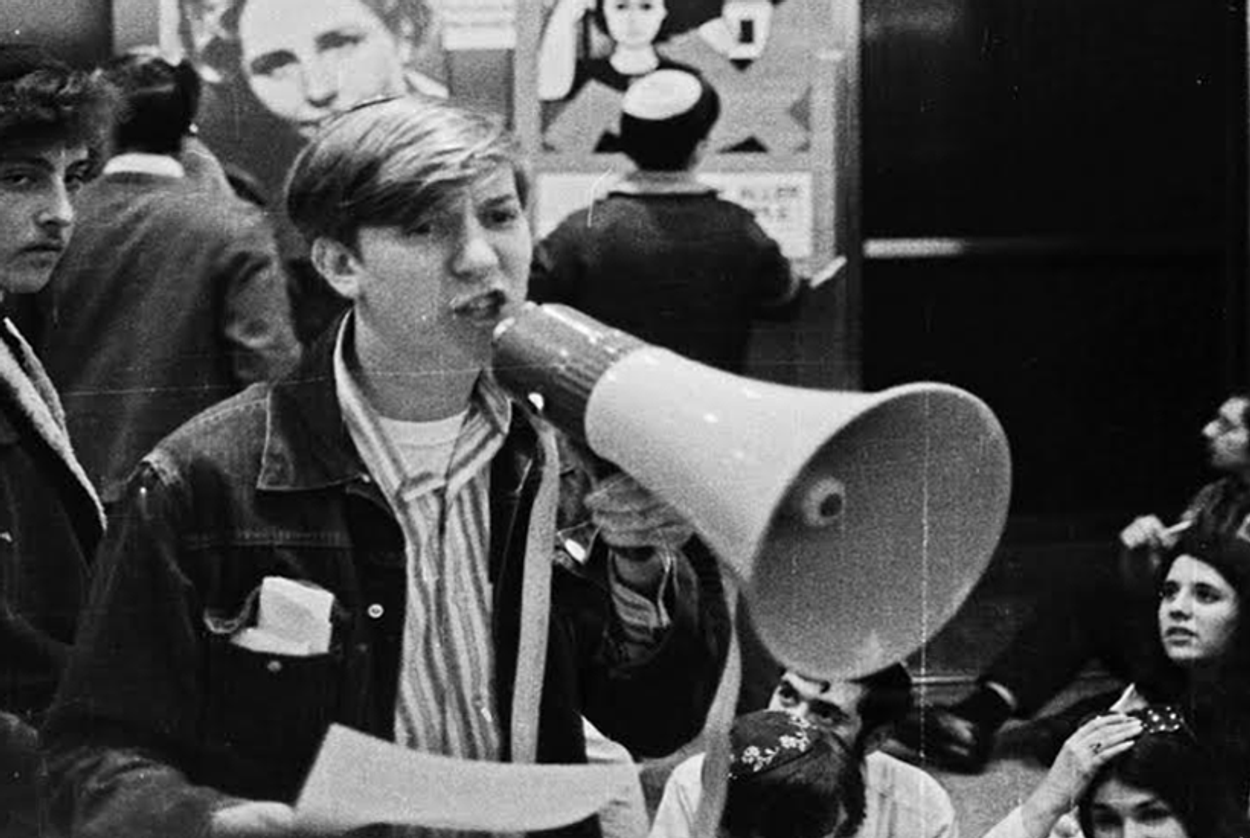

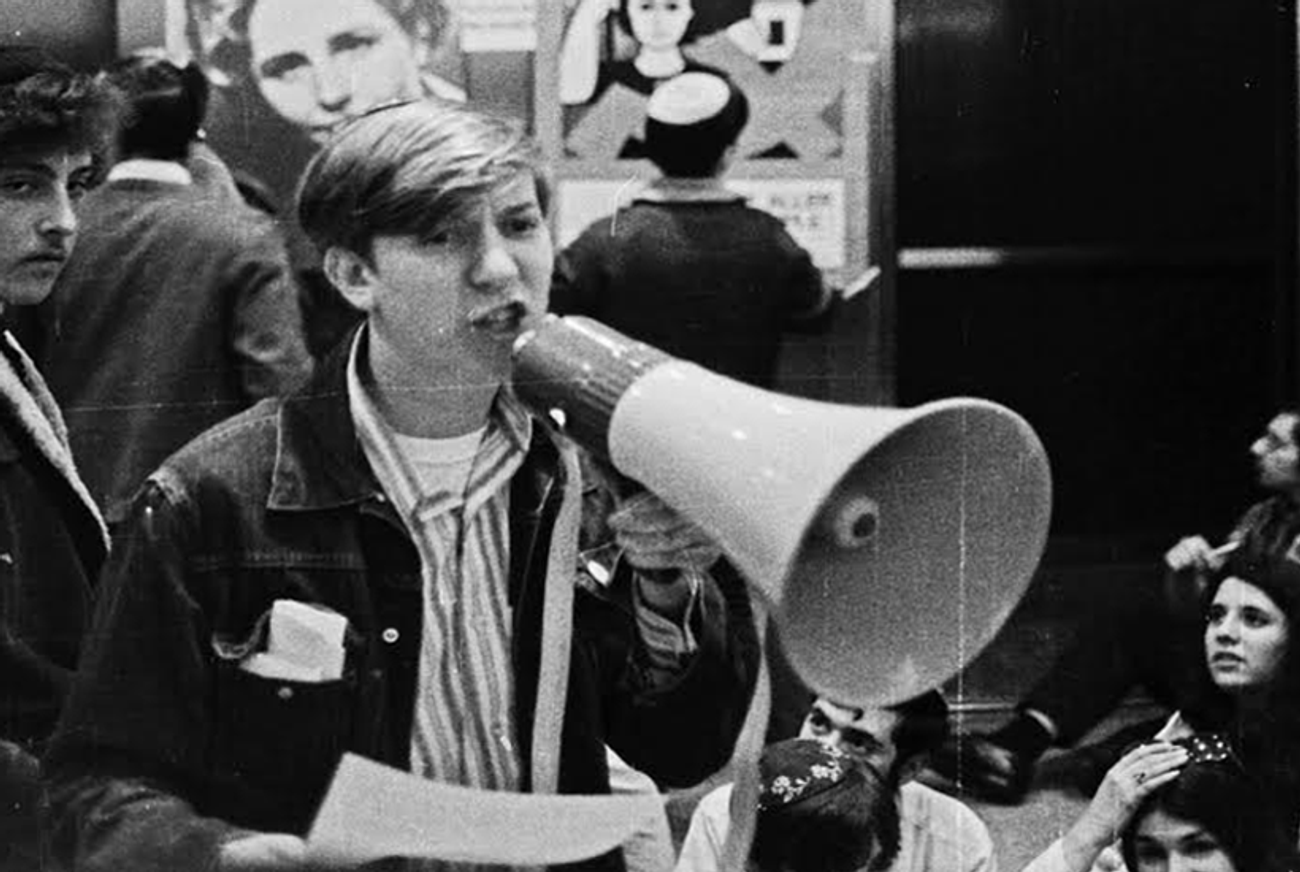

The hijacking trial began on Dec. 15.Glenn Richter organized an emergency rally at the Soviet mission, during school hours. I went to the three senior Talmud classes, asked their rabbis for permission to make an announcement, and said, There will be a mass walkout at recess.

The principal of BTA, Rabbi Zuroff, positioned himself by the front door and glared, trying to intimidate us with his presence. One by one, we passed him and walked out. Then Melvin Pickholtz—my old Betar comrade, still the most timid boy in class and nominated every term for student president as a joke—tried to leave. This was too much for Rabbi Zuroff. “Mr. Pickholtz,” he said, “I’m warning you especially: Don’t go.” Pickholtz stayed.

We picketed on the usual corner, in the usual orderly circle. Despite the crisis, SSSJ didn’t escalate its tactics. No sit-downs blocking traffic, no chain-ins at the Soviet mission gate. I met Moish, leaning against a barricade, blatantly bored. “Ain’t no one gonna give a shit about our nice little rallies,” he said.

Meir Kahane appeared, surrounded by followers. Despite the bitter cold, his white trench coat was unbuttoned, a man apparently too absorbed with important issues to tend to his own comfort.

His smooth young face was handsome but unexceptional. He wore a large black yarmulke over short black hair. When someone greeted him, he smiled and then quickly looked to the ground, his thin shoulders stooped, as if embarrassed by the attention.

I couldn’t take my eyes from him. I was drawn, of course, by the charisma of his notoriety, but equally drawn by the paradox of a seemingly shy man who sought media attention. I assumed he was selfless, sacrificing even his humility for the cause.

The TV cameras gathered around him. Brooklyn Jewry—BTA!—had produced a world-class outlaw, a man whose very appearance made news. Europe’s Jews had died unnoticed, and Kahane was the antidote to our marginality. Thanks to him, Jewish suffering was now headlines. He was the terrorist hero, who finds for his dispossessed people an ephemeral home in the media.

Glenn was addressing the crowd when the chanting began, “Kahane! Kahane!” Moish and I joined in, heckling Glenn with the JDLers. We had crossed the line.

Glenn yielded the mike. Kahane spoke with a stutter. “If Jews d-die in Leningrad,” he said, wincing with the repetition, “New York is gonna burn!”

“Never again!” we shouted, raising our fists, empowering our stuttering savior.

“It is time to take the Soviet Jewry issue off the obituary page and put it where it belongs on page one! I want to see a thousand young J-Jews ready to go over the barricades. But,” he turned to Glenn and smiled, “not today.”

Moish approached Kahane, and they went off to the side, whispering. Then they left together, Kahane’s arm around Moish’s shoulders. A few days later a dozen Kahane followers, Moish included, took over a synagogue facing the Soviet mission. They barricaded themselves on the balcony, shouted through bullhorns at the Soviet diplomats, and announced they were remaining until the end of the trial.

***

Underground accounts of the trial revealed that the defendants had indeed intended to hijack a plane. They’d booked every seat of a small aircraft used in internal flights, so as not to endanger innocent passengers. One of the Jews, Mark Dymshitz, was a licensed pilot; he was to take control of the plane and fly it to Sweden. The night before the anticipated hijacking, the plotters realized they were being tailed. Though the scheme was now doomed, they persisted, hoping their desperation would draw world attention to Soviet Jewry. They were arrested before they even boarded the plane.

The prosecutor demanded the death penalty for two defendants, Dymshitz and Eduard Kuznetzov, who’d already spent years in prison for organizing illegal poetry readings. The verdict came on Christmas Eve: death for Dymshitz and Kuznetzov. Death for a hijacking that never happened.

A few nights later the JDL rallied in a college auditorium near the Soviet mission. Several thousand people filled the hall. JDLers in tight jeans and berets and green army coats wore buttons with the borrowed slogans of black militants, “Jewish Is Beautiful” and “Jewish Power,” and the words “Never Again” printed over the tiny repetitive names of Nazi death camps. I wore my favorite button, “Up Against the Wall Mother Russia,” a takeoff on the Yippie slogan that ended with the word “motherfucker.”

A man with a long mustache extending to either side of his jaw wore a leather jacket with an Israeli flag sewn on the back, like a motorcycle gang emblem. A young black Jew in a yarmulke paced the aisles, waving a giant Israeli flag on a pole. A fat man in a football helmet—ready for action—grinned at anyone who looked at him, raised his fist and said, “Never again!” Across the stage a banner displayed the JDL symbol, a fist cut through a Star of David.

There were rumors of what was about to happen: We would march from the auditorium and divert the attention of the cops, while the group still barricaded inside the synagogue rushed out and forced its way into the mission.

I greeted friends with the black-power handshake, angled as if for a handwrestling match, grasping hands turned into a single fist. A Borough Park acquaintance, Yankel Shlagbaum, held two small American flags. “Nu, Yankel,” I said to him, “what’s the joke?”

“You think the cops are gonna beat someone holding two American flags?” he said, laughing.

Meir Kahane appeared onstage. He looked around at the largest crowd any JDL rally had ever drawn, smiled slightly, and pronounced in Hebrew: “Blessed are you, Lord our God, who has kept us and sustained us and brought us to this day.”

“Never again, never again, never again,” we chanted. Amen, amen, amen.

“American Jews have a hang-up,” said Kahane, moving his yarmulke over his head, back and forth, as if stoking a fire. “It’s called respectability. Re-spect-abil-i-ty. The year is 1943. Stephen Wise and the other American Jewish leaders have just approached Roosevelt to bomb the train tracks leading to Auschwitz. Roosevelt refuses. The Jewish leaders have a problem. What is to be done, now that each day, each day as American Jews celebrate their weddings and revel in their expensive bar mitzvahs, thousands of Jews are being gassed?”

Remarkably, his stutter was gone. He spit his words, not holding them long enough to falter over them. And by repeating words and even entire phrases, he transformed his stutter into rhetoric.

“What would have happened—what would have happened!—if Stephen Wise and all his wise men had called for a hundred thousand Jews to fill the streets of Washington and sit down in cold anger and not move until Roosevelt agreed to bomb the train tracks? What if rabbis had chained themselves to the White House gates singing that well-known Jewish song, ‘We Shall Overcome’?

“Two things would have happened. Two things. They would have all been arrested. And the train tracks would have been bombed.

“But they didn’t get arrested. Jews don’t do such things. It’s not respectable. And so six million Jews died, and American Jews kept their respectability. I say it’s time to bury respectability before respectability buries us!”

This was my father speaking. His lonely indictment of American Jewry was finally being heard. I felt the thrill of his vindication.

Kahane continued: “I know Jews who can’t sleep at night because of their concern for humanity.” He smacked his lips, savoring the sarcasm. “I know Jews who go to jail for blacks and Puerto Ricans and Chicanos and Pygmies. I know rabbis who went to Selma to get arrested. But I don’t know of a single rabbi who broke the law when the crematoria were being fed with twelve thousand Jews every day. Not one Jewish leader even thought of doing what every self-respecting black leader did for his people when the issue wasn’t life or death but permission to sit in the front of a bus.

“Never again will Jews watch silently while other Jews die. Never again!”

“Never a-gain! Never a-gain! Never a-gain!”

“Tonight we have a different Jew, a fighting Jew! But this fighting Jew drives the respectables, the Nice Irvings, up their wood-paneled offices. ‘Violence is unJewish! The Bible says so!’ In the Bible we find the story of a man named Moses, who saw an Egyptian beating a Jew. And what did Moses do? Set up a committee to investigate the root causes of Egyptian anti-Semitism? The Bible says, ‘And he smote the Egyptian.’ ”

Kahane raised a fist and slowly twisted it. “Listen, Brezhnev, and listen well: If Dymshitz and Kuznetzov die, Russian diplomats will die in New York. Two Russians for every Jew!”

“Two Russians for every Jew! Two Russians for every Jew!”

We filled the exits and pushed outside. The night blinked with rotating police lights. In the bitter air our slogans turned to smoke: “We are Jews, we couldn’t be prouder, and if you can’t hear us we’ll shout a little louder!” Helmeted cops formed a barricade along the curb, clubs horizontal across their bellies. We were dangerous with rage, no longer pathetic little Jews, no more Nice Irvings.

We practically ran the single block to the Soviet mission. I tried to get close to the head of the line, but not too close: to see what was happening; to be touched by danger, the possibility of pain; but still be far back enough to run when the cops began swinging.

We packed onto the pavement, prevented by the cops from spreading into the gutter. There was no room, but still the crowds kept coming, pressing from behind.

A young man in a white karate jacket tied with a black belt shouted, “Let the Reb through, let the Reb through!” They called Kahane “the Reb”—the teacher. The dense crowd somehow parted, and the man in the karate jacket escorted Kahane to the front of the line. Camera crews ran alongside.

Kahane leapt over the farthest barricade and disappeared into a line of cops. I thought: That guy has balls.

The cops charged the crowd, swinging. We linked arms.

“They’re calling us kikes!” someone shouted. “Nazis! Nazis!” we chanted.

Glass shattered. A young woman fell through a Christmas display window; she lay in the glass, screaming. The cops clubbed randomly. I led someone with a bloodied head into an apartment building, down to the basement. The janitor tied a wet towel around his head. We returned to the street.

There was no one to tell us what to do next: The JDL leadership was either in jail with Kahane or barricaded inside the synagogue. We wandered aimlessly, chanting. Irate neighbors shouted at us from above; bags of garbage fell on our heads. Demonstrators pushed into the apartment building, pounding on doors and screaming obscenities, forgetting the cops, the mission, Kuznetzov and Dymshitz. I headed for the subway.

I was home for the 11 o’clock news. We were, of course, headlines. I moved close to the screen to spot myself in the crowd. Instead, I saw Yankel Shlagbaum, blood on his face, glasses skewed, in either hand an American flag.

From Memoirs Of A Jewish Extremist: The Story of a Transformation by Yossi Klein Halevi. Copyright © 2014 by Yossi Klein Halevi. Reprinted by permission of Harper Perennial, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Yossi Klein Halevi is the author of Like Dreamers: The Story of the Israeli Paratroopers Who Reunited Jerusalem and Divided a Nation. He is a senior fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem.

Yossi Klein Halevi is the author of Like Dreamers: The Story of the Israeli Paratroopers Who Reunited Jerusalem and Divided a Nation. He is a senior fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem.