With Civil War Looming, Ukrainians Agree on One Thing: No One Knows What’s Next

Jews in Kiev say the protests were about democracy; others in Odessa believe the Maidan was full of Nazis. Now what?

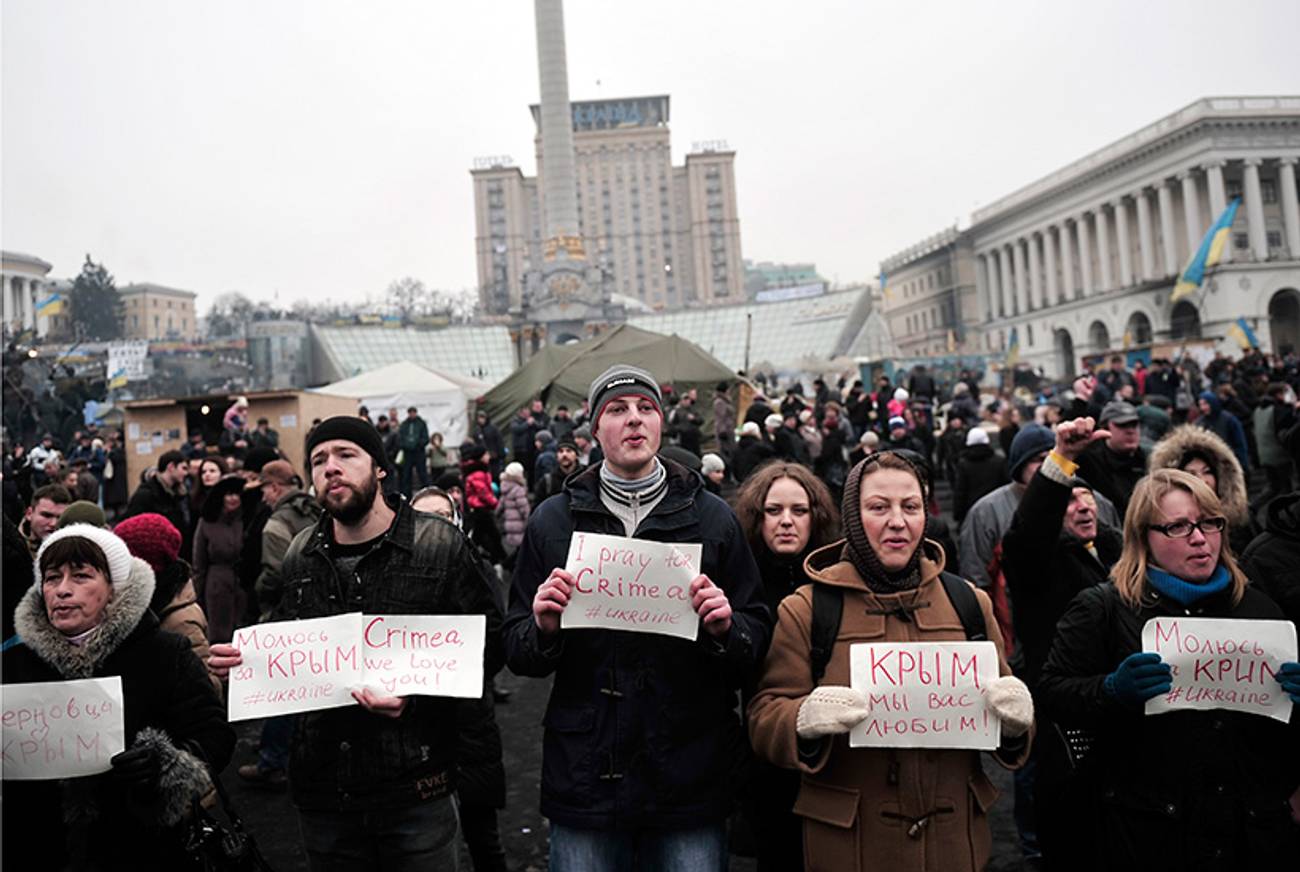

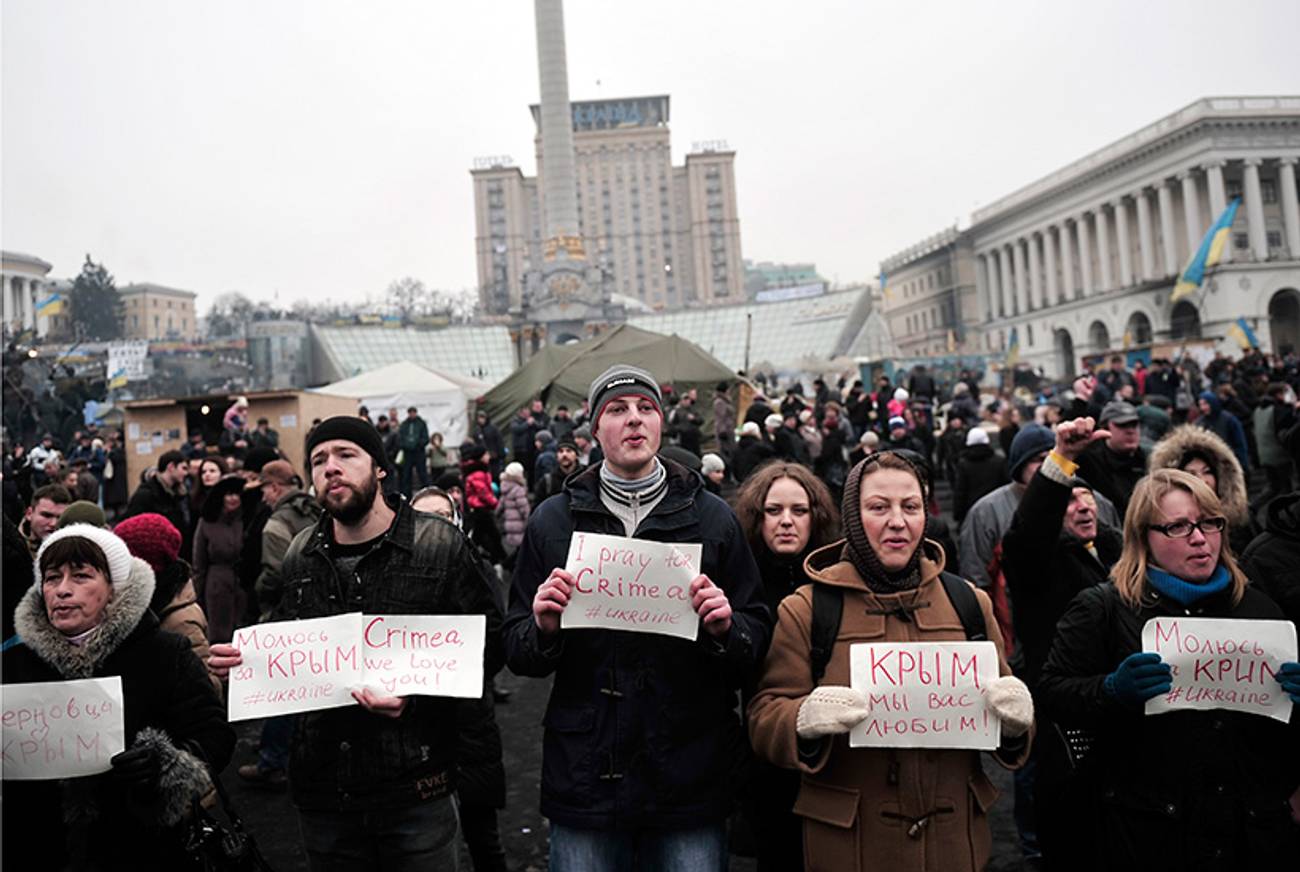

In the past week, it has become clear that the popular ouster of Ukraine’s President Viktor Yanukovych marked not the end of a political process that began last November with the outbreak of protests in Kiev, but the transition to a new phase marked by national discord—thanks to the deepening split between the Ukrainian-speaking western half of the country and the Russian-speaking eastern half.

Now Russia’s leader, Vladimir Putin, is exploiting that divide with his occupation of the Crimea. Putin and his foreign minister, Sergey Lavrov, have defended Russian actions by claiming that they are protecting Ukraine’s Russian minority as well as combating the anti-Semitism espoused by some elements of Ukraine’s far-right nationalist movement.

But Jews in Kiev who participated in the Maidan protests say there isn’t any need for Russia to step in on their behalf. “I know hundreds of Jews who stood on Maidan,” said Arseniy Finberg, the 31-year-old director of a tourist company and father of two who participated in the demonstrations in Maidan before they got violent. Finberg said allegations that anti-Semitism tainted the protests are largely exaggerated. The handful of attacks on Jews in the square—including someone who had a drink poured on her when she tried to stop young nationalists from putting up anti-Semitic posters—were unusual and, he suggested darkly, the work of those looking to discredit the Maidan movement.

Finberg described the Ukrainian-born Israeli soldier who participated in the Maidan, the klezmer band he saw there, the demonstrators in tzitzit and kippot. “All the people around me support people who started Maidan,” Finberg told me. “I am happy that we managed to destroy the former government of Ukraine because it was full of corruption. Maidan has made a strong self-consciousness, a real achievement, that people control all the acts of government on all levels.”

For Alexander Roitburd, one of Ukraine’s most famous artists, the country’s future depends very much on bringing the rule of law to Ukraine and gravitating toward what he sees as Western values. He, too, participated in the protests in Kiev, where he lives. “Maidan is not political, but a set of values,” Roitburd, who is Jewish, told me through a translator over Skype. “It was a geopolitical choice. Is Ukraine’s future in the context of modern civilization, or forever trapped in a post-Soviet space?” Roitburd says that in modern countries, government is a service provider that requires management, whereas in Russia, it’s a sacred force. “The historical traditions of Ukraine gravitate toward the management point of view,” he told me. “Can we allow mindless people to drag us into a third World War?”

Yet there are plenty of people in Ukraine and beyond who believe the whole Maidan movement—which erupted over the question of a trade agreement with the European Union—is about money, and power. Suspicion of the West, of Western nongovernment organizations, and Western-facing oligarchs runs high in the eastern part of the country, driven in part by the history of Western support for the civil protests of the Orange Revolution, a decade ago.

Roitburd insisted the Maidan was a spontaneous civil movement that succeeded in attracting the support of the country’s richest men, not the other way around. “I paid, the whole of Kiev paid, starting with babushkas bringing potatoes and ending with oligarchs,” Roitburd told me. “The owner of the largest book chain in Ukraine stood from morning till night cooking borscht and frying shish kebab. My business friends collected money for children who lost parents at the Maidan.” When asked if people were paid to protest, he said, “Millionaires stood there. The cars were foreign cars. To pay those businessmen it will cost a lot of money.”

Rather, he went on, “It was a revolution of everyone from the lowest people to the oligarchs, who secretly helped. They put their eggs in different baskets. Officially, they were party members. Unofficially, they invested in Maidan.”

Both Finberg and Roitburd said that now they favor the decision to appoint oligarchs as temporary governors. “Those people are very influential,” Finberg said. “Those people can make order in their regions.” One goal of the revolution which ousted Yanukovych was to put an end to the extreme corruption of his regime—a degree of venality evidenced by the private zoo, golf course and other luxuries discovered on his closed presidential compound after he fled late last month. When I asked if empowering oligarchs politically could lead to a similar form of corruption, Roitburd simply replied, “You can’t solve all the problems at once.”

***

In eastern Ukraine, the perspective is quite different. “The nationalists are Nazis,” said Inna Olar, a Jewish 55-year-old information-technology manager who lives in Odessa, the Black Sea port in the south of Ukraine. She called them anti-Semites and cited their symbols—which are derived from those used by the SS—and their reverence for the nationalist hero Stepan Bandera, who saw Jews as agents of Soviet imperialism. She says she is against the new government, which she doesn’t view as legitimate. “It came to power in a coup,” she said, “and their first law was to repeal the language law.”

“They were not for Ukraine,” agreed a woman who lives in Donetsk and who asked not to be identified by her real name but offered up “Svetlana” instead. Speaking through a translator via Skype, she called the Maidan protesters terrorists. “All of Ukraine thinks that,” she said. “No one came for himself. They came to earn money.” She told me she’d been on a trolley recently and overheard a group of miners saying they had been offered 10,000 hryvnia—about $1,000—to join the protests. “All the people there were paid,” she told me. “It’s not their own feelings.”

Yet, unlike Finberg, she knew no one personally who was in the square. From Kiev, Finberg told me he’d heard just the same about the pro-Russian groups that turned out to oppose the Maidan protesters: They were brought centrally by buses and were paid by the Yanukovich regime. Then there were more protests, he added—“People who promised money didn’t pay them.”

The one thing unifying everyone I spoke with was dissatisfaction with Ukraine’s current condition—specifically, with the economy. And the splits that manifested in comments about national or ethnic identity were reflected again in people’s views on whether closer trade ties with the West would help or hurt Ukrainians. “We do not stand to benefit,” Inna Olar insisted. “Our products are not competitive. The Europeans won’t buy our milk. It’s not our mentality. We need 400 years.”

Olar had no love for Yanukovych and sounded hopeful about the future triggered by Maidan’s success. In the post-Maidan era, she said, there will be no more dictators, no more totalitarian regime, and no more Yanukovych. “Yanukovych was a totalitarian leader,” she said, “so it’s a step toward democracy. The nationalists aren’t here for long, just until May, when a reasonable person will hopefully stand up for the elections.”

But even within Odessa, not everyone agrees. Berl Kapulkin, the press secretary of the Jewish community in Odessa, wrote in an email that while he does not support the nationalists, “We support peace for all nations and states and support Ukraine as independent democracy.” Unlike Olar, he said that most people who protested at the Maidan are not anti-Semitic, and though the crisis was not good for the Jewish community nor for Odessa generally, he, like Olar, is hopeful for the future. “Furthermore, today in Odessa became the new Governor, Mr. Vladimir Nemirovsky,” he wrote. “He is a Jew and a great friend to our community.”

But in Donetsk, “Svetlana” was less hopeful. Donetsk, Yanukovych’s hometown, is overwhelmingly Russian-speaking; 75 percent of the population voted for Yanukovych in the last election, in 2010. With Putin’s army on the border between Crimea and Ukraine, she said, she fears a civil war. “The West is afraid of civil war just like the East,” she said. “But someone very much wants this.” Who? She wouldn’t—or couldn’t—say.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Batya Ungar-Sargon is a freelance writer who lives in New York. Her Twitter feed is @bungarsargon.

Batya Ungar-Sargon is a freelance writer who lives in New York. Her Twitter feed is @bungarsargon.