Rabbi Noa Kushner opened a recent Shabbat evening service at San Francisco’s The Kitchen with a quote from Abraham Joshua Heschel: “It is customary to blame secular science and anti-religious philosophy for the eclipse of religion in modern society,” she read. “It would be more honest to blame religion for its own defeats. Religion declined not because it was refuted, but because it became irrelevant, dull, oppressive, insipid.”

The service that followed was anything but dull: It was high-octane, all in Hebrew, and musical. The Kitchen, which Kushner founded in 2011 after working at Hillels at Sarah Lawrence College and Stanford University and as a congregational rabbi, describes itself as a “religious startup,” one of a number of independent Jewish congregations that do not slot themselves into traditional denominations, or even into the standard format of a synagogue. “What we’re looking at,” Kushner said in a recent interview, “is creating not an institution but what we affectionately call a solar system,” in which the city offers a variety of Jewish experiences that may not connect directly to attending services.

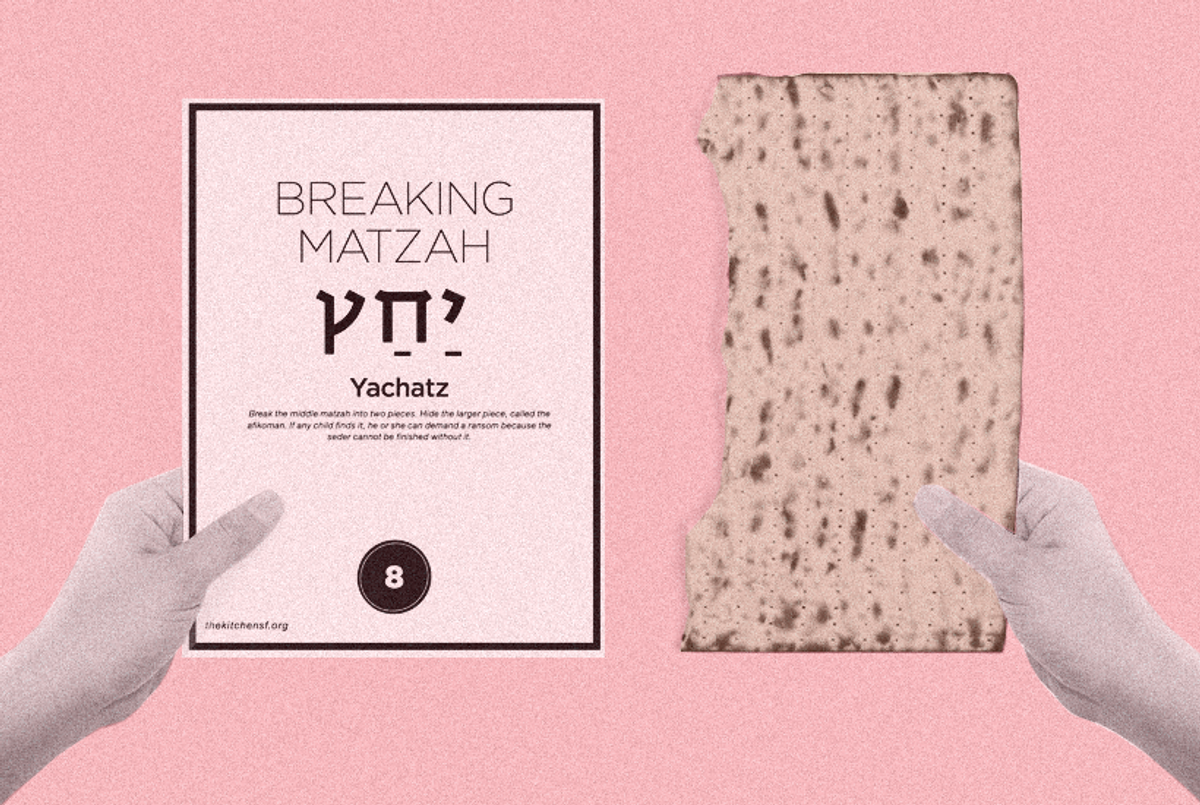

Here are some of the planets in that solar system: For Shavuot last year, The Kitchen held a scavenger hunt in which participants acted as Ruth and received text message directions from Gabe Smedresman, a Kitchen member, acting as Naomi (including instructions to study Torah for 15 minutes in a café). The Kitchen staff (three full-timers) is currently choosing hosts for a program of in-home Shabbat dinners. And just a couple of weeks ago, in mid-March, The Kitchen released an updated version of its Passover game, Next Year in Jerusalem. The game, which debuted in a pre-holiday rush last year, involves a deck of cards split between “ritual” cards, which are used in a precise order to guide participants through rituals of the Seder, and “action” cards, to be used at any time during the evening’s proceedings, which offer prompts to “reflect,” “act,” or “discuss.”

The new edition of the game was created in response to user feedback, just as startups improve their products based on user input. That similarity is intentional, said Yoav Schlesinger, the Kitchen’s executive director, not just because the organization is based in the startup-heavy Bay Area but “because we think it’s on point. It’s all about rolling things out quickly, getting customer feedback, meeting the needs of the market, making changes based on the feedback you get. It’s a conscious effort on our part.” The “product,” as Schlesinger put it, is Torah, the same product Judaism has offered all along. But The Kitchen, like a handful of kindred communities established in the past decade, is “trying to innovate around how we deliver that to people.”

***

When Kushner first conceived of The Kitchen, she was working as a rabbi at Rodef Shalom, the same congregation as her husband, Rabbi Michael Lezak. “I love the people there, and it’s a beautiful place,” Kushner said. But she wanted to create something new. Kushner’s father is Rabbi Lawrence Kushner, who ran what Noa Kushner describes as “sort of an alternative community” at his Reform synagogue in Massachusetts the 1970s. The elder Kushner’s synagogue was “doing things that are now commonplace but were countercultural at the time,” Kushner said, including participatory singing, text study, and use of Hebrew. “There was an understanding that Jewish practice, religion, ideas, experiences were not perfunctory, either socially or religiously. … Culturally there was a sense of humor and informality.” The reason she was looking for something else, Kushner said, is that her “normal was quite alternative” already.

While Kushner had been formulating the beginnings of The Kitchen, other rabbis around the country were already growing similar congregations—independent and unaffiliated with any denomination. (These congregations differ from the Newton Centre Minyan, Kehilat Hadar, and Darkhei Noam. Those three are independent, lay-led egalitarian congregations and tend to be Conservative in observance.) New York City’s B’nai Jeshurun synagogue was a kind of “incubator,” explained Leah Hochman, director of the Louchheim School for Judaic Studies and associate professor at Hebrew Union College in Los Angeles and a student of the contours of American Jewish observance. “There was something joyful about the Judaism they were generating,” she said, and people were welcome at services even if their Sabbath observance was non-traditional. In 2004, Rabbi Sharon Brous, a B’nai Jeshurun Rabbinic Fellow, founded Ikar in Los Angeles. Today Ikar is considered an inspiration for many similar communities, where “a charismatic leader and a group of committed laypeople … create a Judaism that they want to participate in,” Hochman said. At the same time, Judaism “jumped from the institution to social media, so that membership meant your attention and your intention rather than your money.”

As she cast around for model “religious startups” that would help her articulate her vision, Kushner came across Ikar and Kavana, another independent congregation, in Seattle, which had been co-founded in 2006 by Rabbi Rachel Nussbaum. She shared elements of Kushner’s background: She had been a Hillel rabbi and then a rabbi at a large suburban congregation. She saw a “huge gap” between what Seattle’s religious institutions were offering and what younger Jewish residents were actually looking for. What they wanted, Nussbaum said, was something more like “a Hillel for adults” than a traditional synagogue. Today, Kavana operates on a co-op model, where people join as partners rather than simply members—they volunteer their time, participate in community governance, and have access to some of Kavana’s financial information. The goal is “a platform to give people the tools and resources to create Jewish experiences and Jewish life for themselves.”

Kushner flew to see Brous and Nussbaum for advice, and when she returned to San Francisco, it was to a group of people intrigued by her ideas. She tried a few experiments in her congregation in Marin County but soon branched out on her own to work in San Francisco, “where the people were that I thought I was going to serve.”

The demographics are important: “Whatever the community form is,” said Nussbaum of independent religious communities, “whatever the institutions are that are built, they have to fit the vibe and the culture and the flavor” of their place. In San Francisco, an element of that flavor is residents’ investment in the city, the idea of “reclaiming your neighborhood to make it work for you and your family,” Hochman said. The Kitchen offers a Jewish slant on that idea.

Today, The Kitchen has 183 member households, with most members in their 30s and 40s. Many come to The Kitchen at transitional life moments, when they get married or have children. Jessie Elliott and her wife joined The Kitchen about six months into its existence, having realized they wanted a community in which they could pass Judaism down to their children. The Kitchen “was funky and interesting and contemporary,” Elliott said. “One thing that Noa does really well is the education piece, and making the education that she’s offering really interesting and relevant, something to think about and integrate into your daily life, and make you a better person.” Roughly 150 people show up for services on Shabbat and about half that for Shabbat dinner with food supplied from local restaurants. The Kitchen rents space in a Quaker school in the city’s Mission district for its services and dinner.

Kushner describes herself as a “traditionalist” when it comes to Sabbath prayers. But beyond worship, growing the community has involved a “steep learning curve.” She has had to reframe some of her rabbinic preconceptions. “When I was right out of rabbinic school, if you came to me and said, ‘I want to have a bat mitzvah for my kid in six weeks in Barbados,’ my eyes would have rolled back in my head,” she said. “Now I think, here’s someone who wants to do something Jewish. They don’t want to buy a handgun, they want to have a bat mitzvah. They might have an unrealistic expectation about how that’s going to happen, but my job is not to close the door, my job is to open it.” To that end, The Kitchen created its own prayerbook, with translations and interpretations of prayers, in an effort to be inclusive of everyone who might join them.

At the same time, the rabbi is not central to Jewish life at The Kitchen. “If I create a situation where people feel like in order to have a Jewish experience, they have to be around me, then I’ve failed,” Kushner said. Instead, Kushner wants members of her community to have Jewish experiences on their own time, in their own groups.

Because The Kitchen doesn’t have a daily minyan, making the Jewish experience available sometimes means referring members to another congregation. “If they ended up wanting to join that place, I would think of it as a huge victory,” Kushner said. Rabbis in the area seem to feel that The Kitchen’s existence is a boon, not a drain on membership. “One of the reasons I think The Kitchen is a bright light is that the old structures really don’t seem to be holding up in terms of reaching assimilated Jews,” said Rabbi Camille Shira Angel of Sha’ar Zahav, a Reform synagogue also located in San Francisco’s Mission district. “I think there are enough Jews whose needs aren’t yet getting met as Jews to go around.”

In a way, Passover is the perfect example of how to fulfill the goal of encouraging people to have their own Jewish experiences. “People do it at home, they do it all different kinds of ways,” Kushner said. “Nobody’s watching.” The Kitchen’s Passover game uses ritual as the starting point for discussion: a card inspired by the Jews’ experience in Egypt asks players to discuss how their own cities could “be a ‘narrow place’ like Biblical Egypt;” a card about the Seder plate invites people to add something to the plate and explain why. When Kushner used the game at her Seder last year—with her husband and her father, both also rabbis, in attendance—“it brought so much life and energy to the Seder. Even my dad liked it. And it was fun. It really did change things.”

***

Newer communities in the independent minyan mold have it easier, in some ways, than traditional synagogues. They are more limber, with less of the institutional baggage that might hamper change in an older organization. But independent congregations face challenges, too. Many are, like The Kitchen, determined not to rent or own a core space, on the theory that upkeep drains an organization’s budget and that central spaces are less necessary to the planets-in-a-solar-system model of operations. The downside, said Nussbaum, is “a lot of schlepping.” Membership and finances pose questions for independent communities as they do for synagogues—the two types of organizations merely come at those questions from different angles. Kavana, in Seattle, has settled on a “blended model” of financing that mixes programming income, fundraising, and other internal and external sources of funding. Still, Nussbaum said, there are trade-offs. In any open community, “there are always going to be people who aren’t quite paying for what they’re receiving.”

Last year, The Kitchen sought advice from design firm IDEO, a consulting firm that advises organizations on design and branding, about how to articulate its mission and refine its approach going forward. Now Kushner is in a round of fundraising to finance future Kitchen initiatives, including a Shabbat pop-up store that would sell white tablecloths, Judaica, and Shabbat reading material, and a food truck that could give rabbinic advice to passersby on anything from cooking to whom to marry. The idea, Schlesinger said, is “that, once upon a time, if you lived in a small, tight-knit Jewish community, there were people to call when you had a question, when you had a problem.” Just because Jews may no longer live in tight-knit communities doesn’t mean those questions no longer exist or that they should go unanswered.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Sara Polsky is the features editor at Curbed and author of the novel This Is How I Find Her. Follow her on Twitter @sarapolsky.

Sara Polsky is the features editor at Curbed and author of the novel This Is How I Find Her. Follow her on Twitter @sarapolsky.