God, under pressure from his investors, was finalizing his sketches for Mankind when he realized he had a problem. He wanted Man to praise him, to thank him, to glorify his name (he hadn’t yet created “self-esteem”), but in order for Man to glorify his name, Man would have to say his Name.

God was no idiot. God knew that if Man ran around saying his name too often, eventually God’s name would become powerless and insignificant; soon enough, Man would be calling it out while tugging his wife’s hair and hoping the kids didn’t walk in. So step one, God created another word: “Forbidden.”

Then, the commandment: “Don’t. Say. That. Word.”

Or else.

Some years later, Lenny Bruce would make the same observation as God (personally, I think God got the idea from Lenny), this time regarding the N-word used to denigrate African Americans. Endless repetition, said Lenny, repeating the word endlessly, would eventually cause the word to lose its power.

So, my fellow Jews, let’s talk Nazis.

Recently, the digital platform Substack came under fire for what a journalist from The Atlantic deemed its “Nazi problem.” There were Nazis on Substack, the journalist journaled, and Nazis were bad, and Substack was bad for allowing Nazis, and not only were the Nazis profiting, but Substack was profiting from the Nazis, too, and the Nazis were only going to get worse, which is what Nazis do, the lousy Nazis. The national news media picked up the story, the outrage machine kicked into high gear, and early this week, Substack took the Nazi Substacks down.

God has rather draconian opinions on free speech, but some of us mortals have tried to do our best to protect it, minorities in particular, knowing that the sword of censorship maims none so mortally as the powerless. Most often, we talk about protecting its free use, but I’d like to speak here, Jew to Jew, about another form of protecting speech, and that is protecting words from overuse.

Because words matter.

“I am all these words,” wrote Samuel Beckett, who worked for the French Resistance against the Nazis, “this dust of words.”

We should protect these words. These are our words.

And words die. They expire from overuse. They wither by want. And the word Nazi is on life support.

When I was a child, the word Nazi was rarely used, if ever. Someone might have been a bigot, or a Jew-hater, or, when it was really serious, an antisemite. But only a Nazi was a Nazi. Nazis were the demonic soldiers in the newsreels we were shown on Holocaust Memorial Day, from the very first grade in yeshiva, laughing as they bulldozed corpses of Jews into hideous gray heaps and set them afire. Nazis were the ghouls shooting naked children in the back and smiling as their once-warm, once-cuddled, nevermore bodies tumbled lifeless into the mass grave below.

The word had power. The word could shake the earth. The word was sacred.

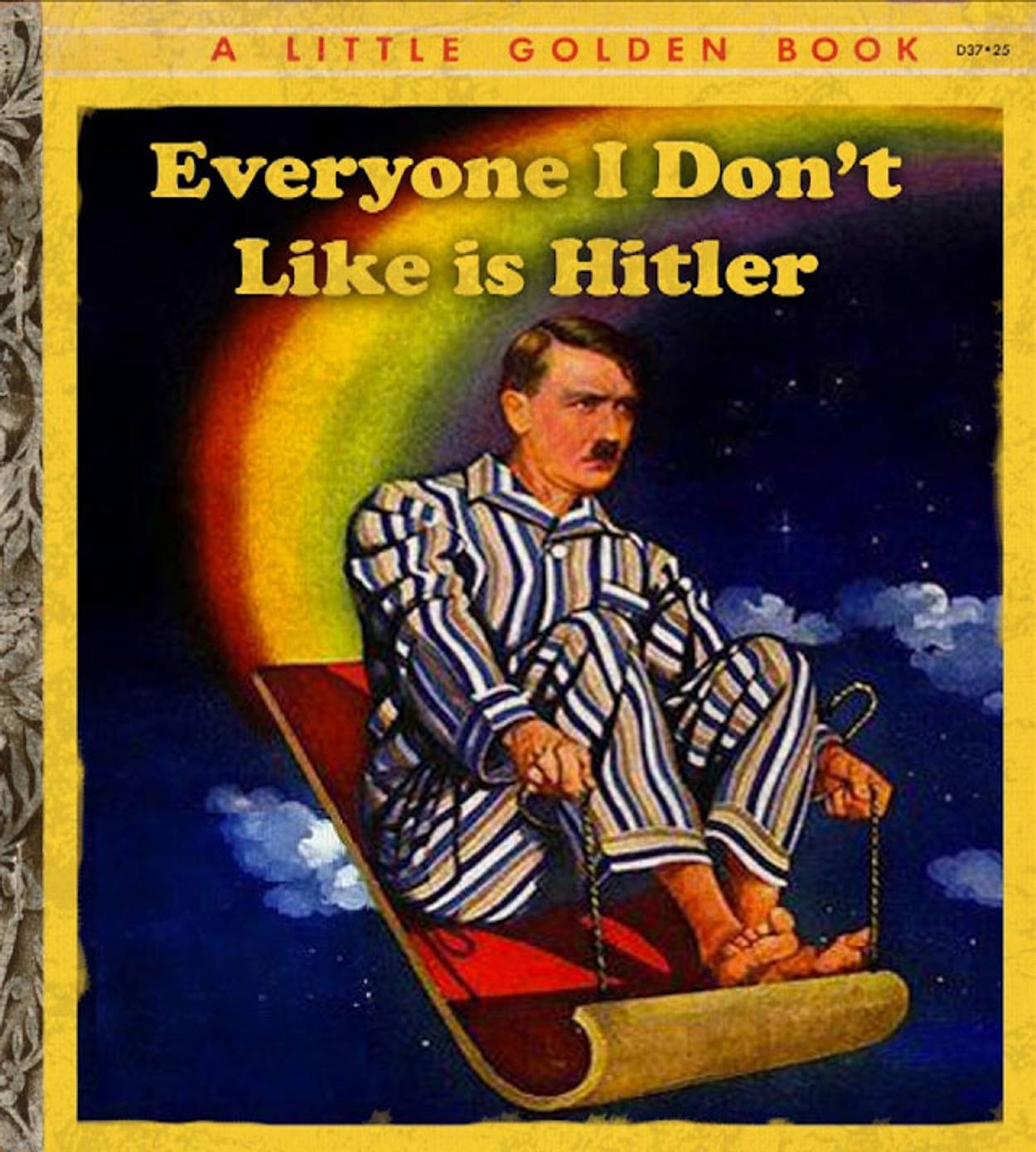

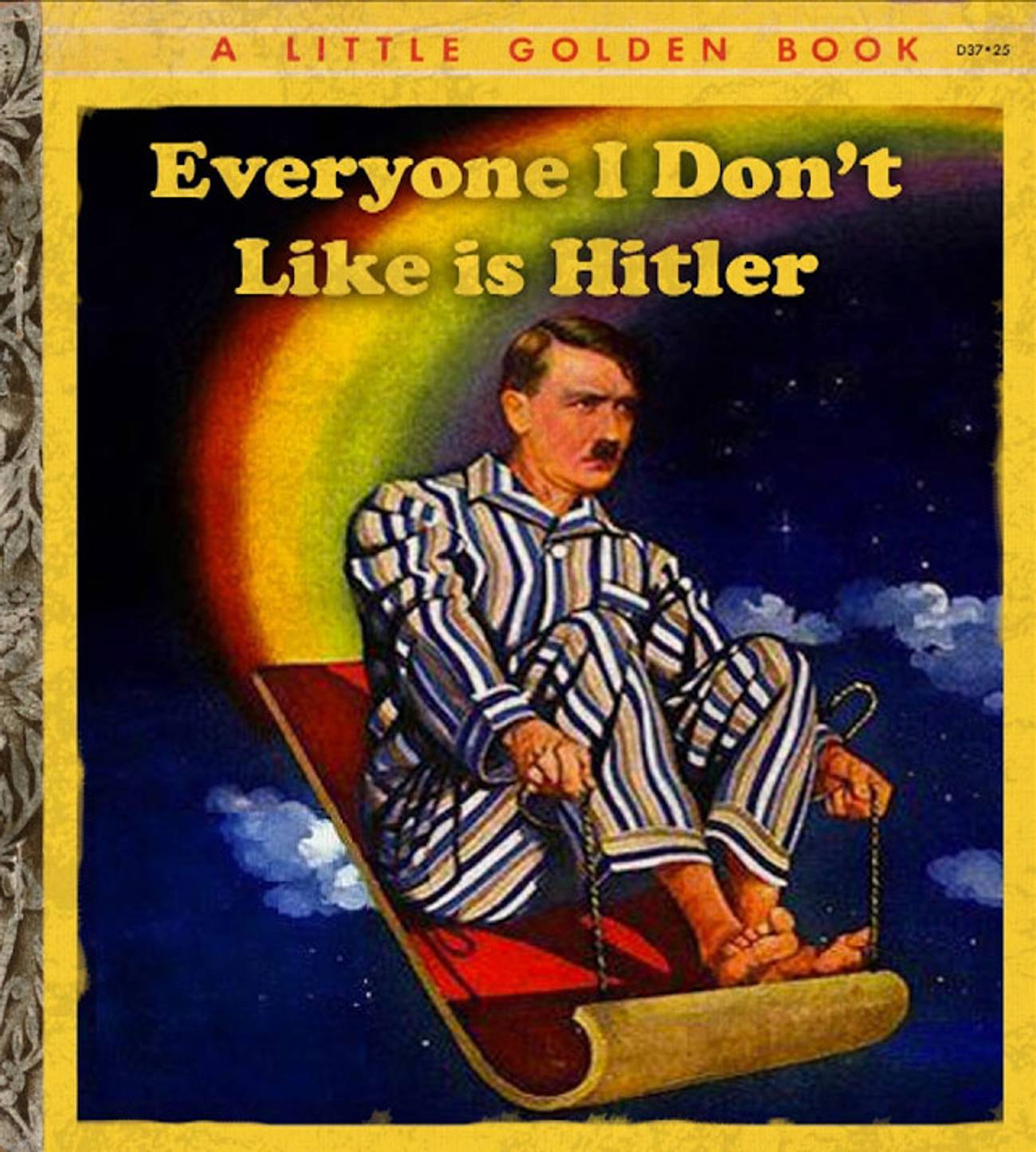

And then something changed. Suddenly, it seemed, everyone was a Nazi. Jesse Jackson was a Nazi. David Bowie was a Nazi. The president of the United States, whoever he was, was a Nazi, a Nazi whose Nazism was defended by what people in my community often referred to as “The New York Nazi Times.” Our Catholic neighbor was a Nazi just for driving past our house on Friday night. I gasped when I first heard it used so cavalierly; something holy had been profaned.

And slowly, the word, as God knew it would, began to lose its power.

Today, like other degraded words, words that once had crucial, pivotal power but are now exhausted, words that society desperately needs like “racist” and “sexist” and “homophobe,” the word “Nazi” has been made impotent and toothless. If I was a theorist of a more conspiratorial bent, I would suspect a secret plot to destroy the word, to reduce it to nothing, a linguistic form of Holocaust denial: What can’t be denied can at least be minimized.

Some months ago, the Anti-Defamation League announced that acts of “antisemitism” have increased by a significant degree. What they didn’t announce was that they had changed their definition of the word antisemitism to include any and all criticism or protest of Israel—so of course antisemitism increased; if they’d included choosing the croissant over the bagel, we’d have a full-blown genocide on our hands. By the ADL’s current definition, I am an antisemite. And Etgar Keret, a longtime critic of Netanyahu, is an antisemite. The 70,000 Israelis I marched with this past summer in Tel Aviv against Netanyahu are antisemites, and the hundreds of thousands of Israelis that protested Netanyahu over the past year—some 60%-70% of the nation’s entire population—they’re antisemites, too.

And so soon the word “antisemite” will be dead, too.

A sixth-grader scrawling a swastika on the wall of his school bathroom is not an antisemite (according to the ADL he is, and they count him in their numbers). He’s an asshole. He also scrawled “Julie sucks dicks.” He may even be a colossal asshole. But an antisemite? Is the word really that cheap? A few months ago, a friend of mine’s sister was out for a pleasant walk with her husband, taking in the beauty of nature and breathing deep of the cool morning air, when a man drove by and shot her husband in the chest. Then he shot her in the face. Her husband likely died immediately; she was confirmed dead last week, Judih Weinstein Haggai, her phone still pinging in a tunnel somewhere under Gaza.

That’s an antisemite.

Words die. We should protect these words. These are our words.

Why do we allow them to be so degraded? Why do we degrade them ourselves?

Would anyone be so sanguine if I were to push my chair from the lunch table, pat my stomach and say, “Boy, I really raped that burger?” Of course not. That word is important. So why are our words any less so? Why are they so cheap? If Kanye West is a Nazi, how bad could a Nazi have been? Is he even worth spending the word antisemite on? Or is he just a mental patient off his maximum-strength, prescription-only, “DANGER: Keep Away From Children” meds? He’s as much a “Nazi” as the lunatic on the streetcorner who called me a “fag” this morning is a “homophobe.” Are ill-informed college students antisemites when they shout slogans they just heard and don’t understand? Or are they just typical self-righteous, know-it-all-while-knowing-nothing college assholes? Lenny himself mocked them, way back in the ’60s, when he joked about one who, while protesting police brutality, berates a man in uniform he thinks is a cop.

“Gestapo?” the uniformed man replies. “You asshole, I’m a mailman!”

If “asshole” is good enough for Lenny, it’s good enough for me.

We have enemies, it’s true; as Delmore Schwartz wrote, “Even paranoids have real enemies.” But Delmore suffered from severe mental illness, and he drank himself to death in such terrible isolation that it was days before anyone even knew he was dead.

Is Nazi, too, already dead? Is antisemite? If they are, who is to blame? If they aren’t, who will keep them alive?

It will have to be us.

The word Nazi deserves protection. We’re the “People of the Book,” after all, words are our wheelhouse, and the God of that Book knew well that a word abused becomes a word without power (I would argue all three of the first Ten Commandments are designed to serve that same single purpose; God wasn’t taking any chances).

Don’t get me wrong, I’m no fan of God’s. He is possessed of a rather authoritarian worldview, and exhibits a deep-seated anger which he blames on us, but he knows how words lose their power.

As it turns out, regarding the Nazis on Substack, reported breathlessly around the world, there were, in total, six of them (the original article, written by a Jew, failed to mention that). To put that in context, my two ultra-Orthodox brothers-in-law have, between them, three times as many children as Substack has Nazis. It’s not even a fucking minyan.

Are the Substack Nazis actual Nazis? I don’t know. If they are, my Israeli nephews alone could fuck them up.

What I do know is that words die from overuse. And once they die, God help us, they don’t return.

Shalom Auslander is the author of Foreskin’s Lament, Hope: A Tragedy, and most recently Mother for Dinner. His new memoir, Feh, will be published this July. He writes The Fetal Position on Substack, so make that seven Nazis.