Sympathy for the Devil

The superstar of old-school terrorism seizes the spotlight in Olivier Assayas’ ‘Carlos’

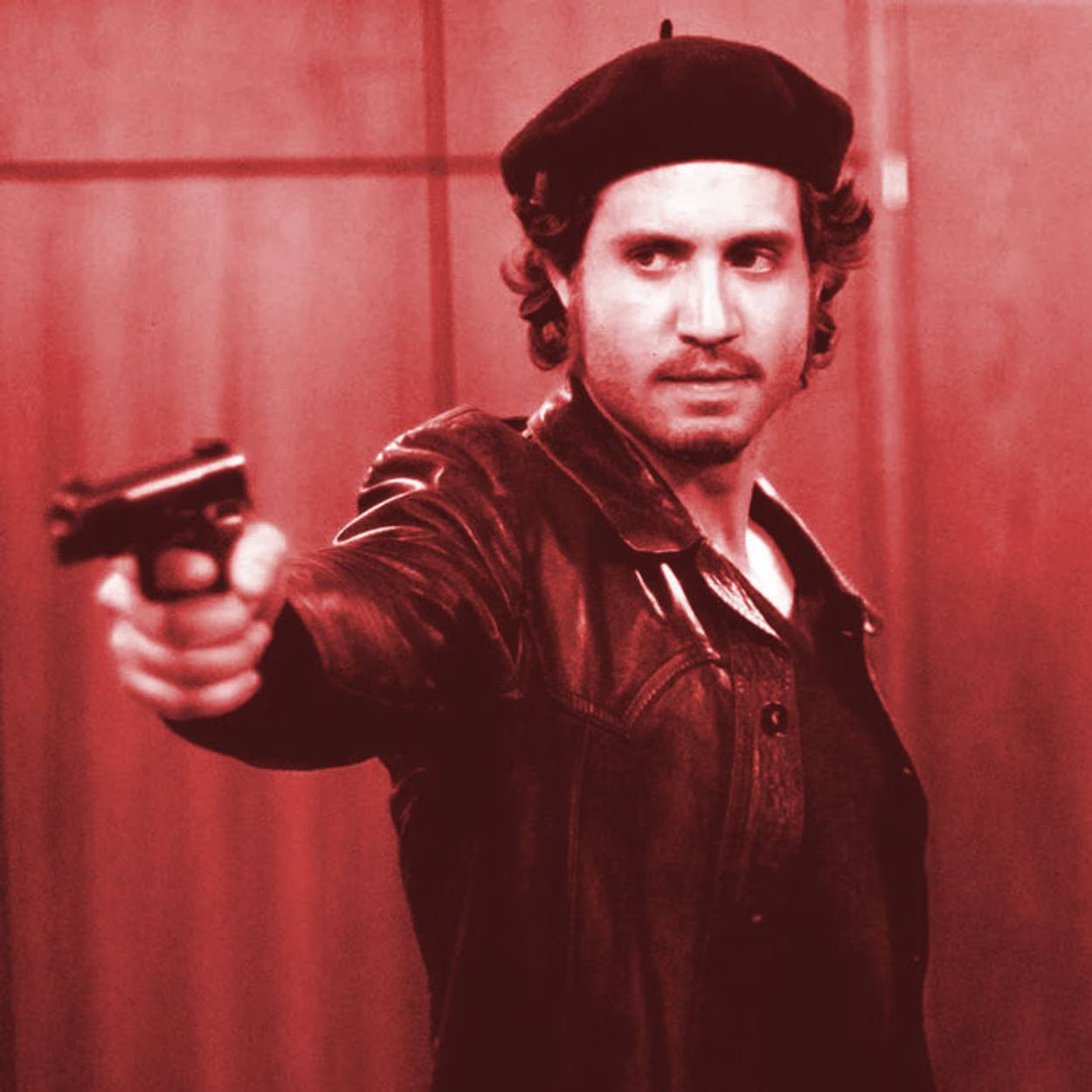

From ‘Carlos,’ directed by Olivier Assayas, 2010

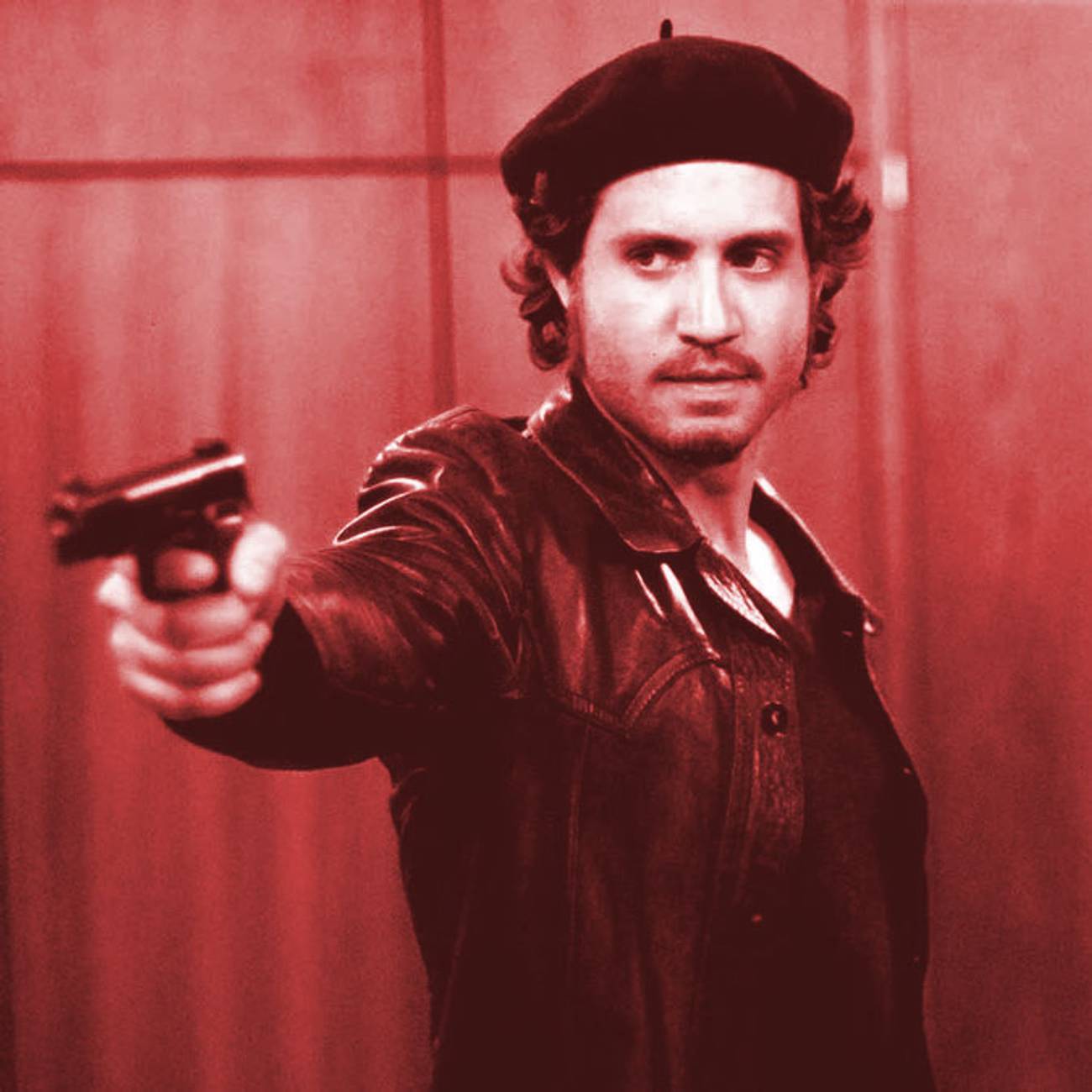

From ‘Carlos,’ directed by Olivier Assayas, 2010

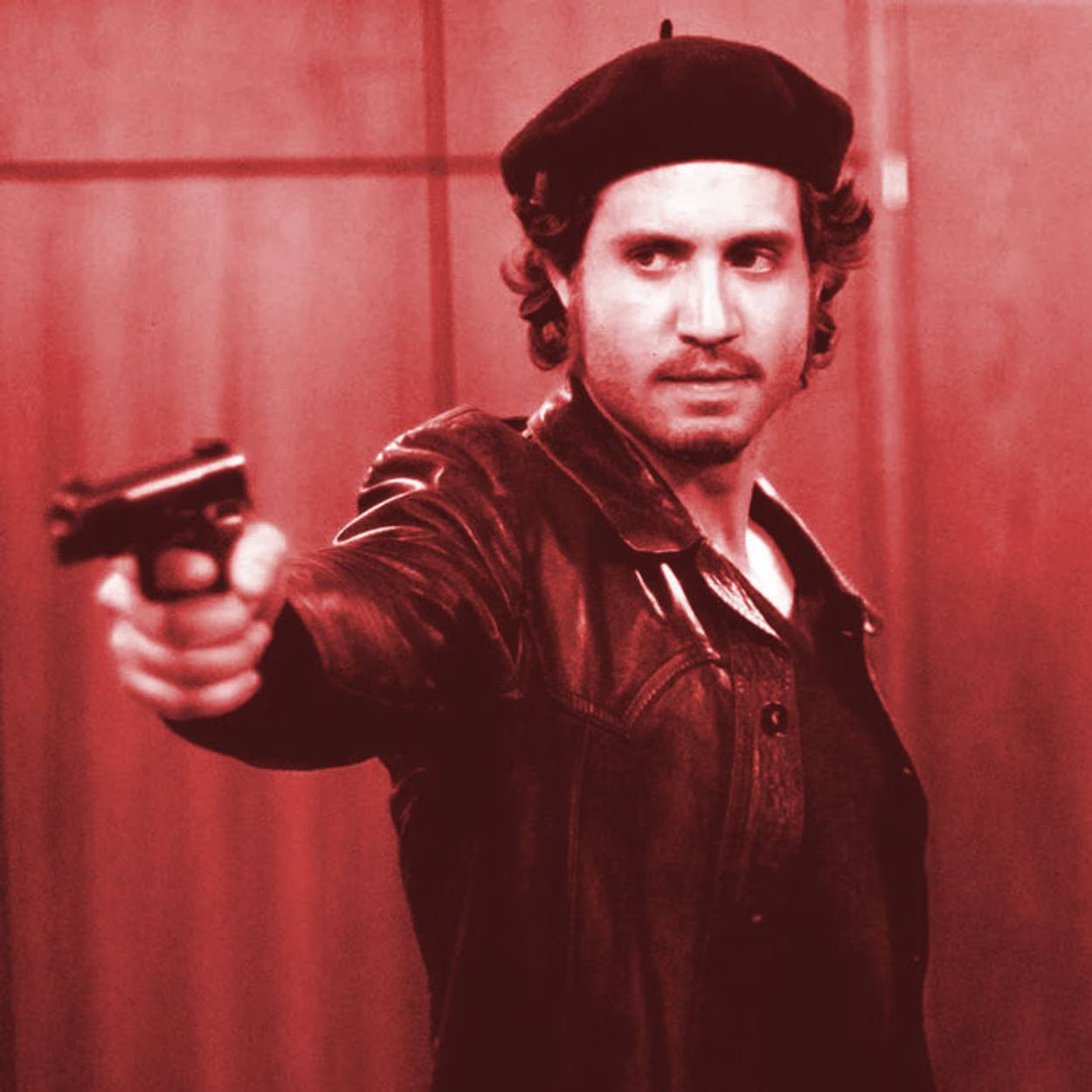

From ‘Carlos,’ directed by Olivier Assayas, 2010

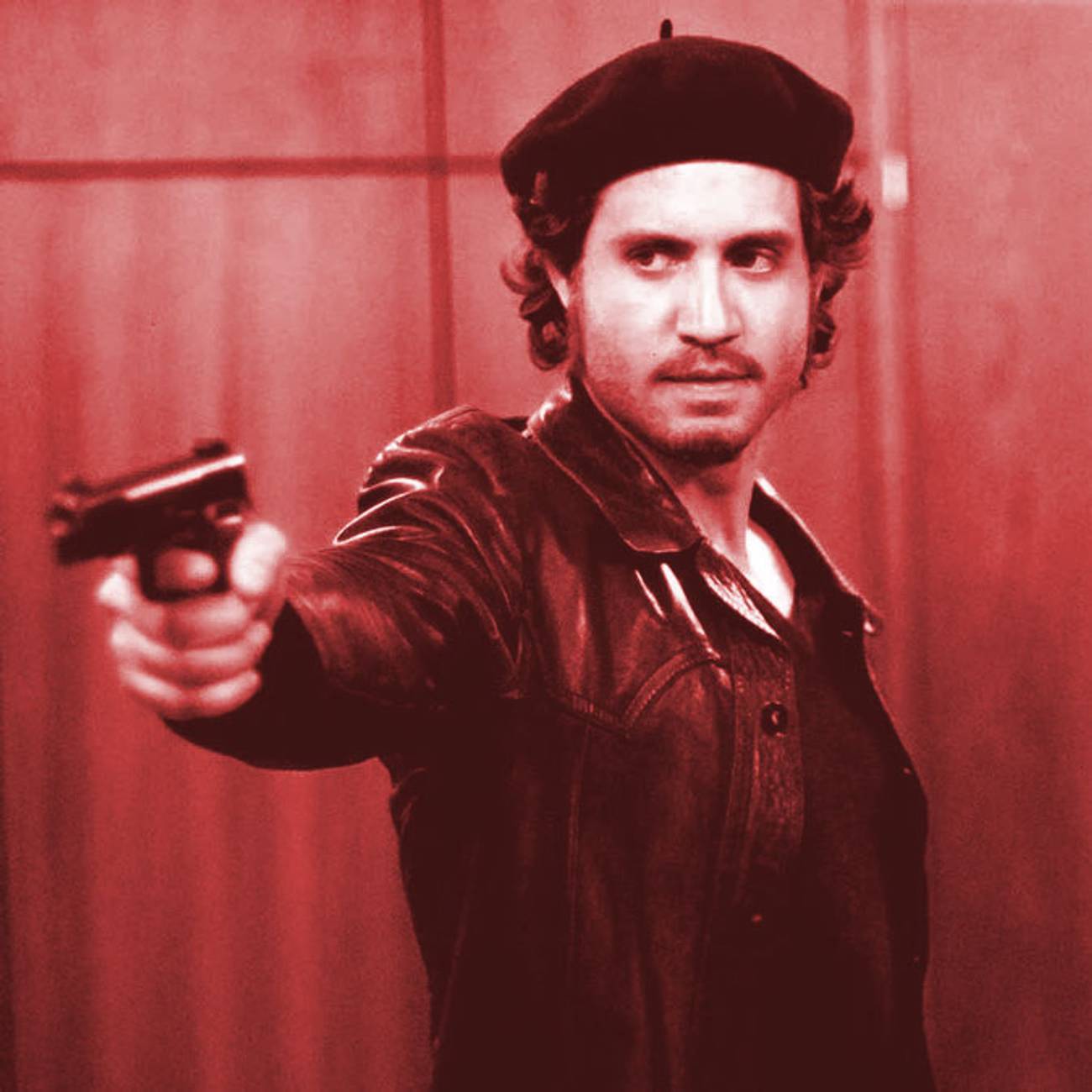

From ‘Carlos,’ directed by Olivier Assayas, 2010

An exclusive full-length screening of the best political film of the 21st century, presented by Tablet, this Sunday, Oct. 22, 2023, 1-8 p.m.

What was it that Marx said that Hegel said about history? The first time as entertainment, the second time as ... entertainment?

Carlos, the ’scope telefilm directed by Olivier Assayas, from a script co-written with Dan Franck, gives Ilich Ramírez Sánchez, aka “Carlos the Jackal,” his cinematic apotheosis.

The basic mode is bang-bang action populated by a large cast of impeccable lookalikes, interpolated with documentary and news footage (some expertly faked), and smartly punctuated by bursts of jumpy reverb-heavy techno-angst. Shown at Cannes as a single 330-minute epic, Carlos was an event, possibly the most universally admired movie among the festival’s official selections. Had Carlos been eligible for the competition, it might well have won the Palme d’Or and perhaps an award for the actor playing its charismatic protagonist—present in every scene and rarely less than outrageously flaunting the conventions of Western civilization.

However one had previously envisioned the mysterious criminal mastermind, the Venezuelan actor Edgar Ramirez, Carlos’ near-namesake and compatriot, is convincingly authoritative in four languages—an appallingly cool killer and megalomaniacal bluffer, a rock-star terrorist and world-class pussy hound, putting a succession of gorgeous young women under “revolutionary discipline” and even, in one memorable tryst, getting one to literally lick his grenade. (“Behind every bullet we fire will be an idea,” this demon lover passionately assures one of his molls.)

No question but that Carlos provides Assayas with a stimulating subject as well as an aesthetic breakthrough. In the 15 years since Irma Vep put the neo in new wave, cine Assayas established two poles: terror and terroir. Assayas movies have alternated between essentially callow multicultural meta-pop globalizing genre flicks (Demonlover, Clean, Boarding Gate) and their antithesis, overly genteel, borderline dull, talk-driven, trés, trés ensemble dramas (Late August, Early September, Les Destinies, Summer Hours). An epic international thriller of many airports, with scenes set in at least 15 different countries (Lebanon standing in for Algeria, Iraq, Jordan, Libya, Sudan, and Syria, as well as itself), Carlos clearly belongs among the former. But the movie is not without its own sense of terroir.

Carlos uses half a dozen or more languages, with almost every actor playing a character of his or her own nationality. Some of the public-figure typage is positively uncanny—it’s a shock to dredge up 35-year-old news reports and see that Sheik Ahmed Zaki Yaniani and Jamshid Amouzegar could be playing themselves—although Ramirez, who resembles the young Val Kilmer more closely than Ilich Ramírez Sánchez, is thus more like “Carlos” than Carlos himself. (His previous roles were apt preparation: the guerrilla martyr Ciro Redondo in Che and the assassin Paz in The Bourne Ultimatum.)

While careful to include a disclaimer noting that, although based on known facts, the narrative is in some ways fictionalized, Assayas makes no attempt at distanciation. The simple addition of faux-18th-century explanatory chapter titles (“In which our hero attends a student party and learns that it is better to shoot first and answer questions never”) could have easily transformed Carlos into Brechtian comedy, but the movie’s aim is total you-are-there immersion. Despite some jarringly anachronistic dialogue seemingly derived from Hollywood action flicks (“At the end of the day ...”; “Listenup!”) and the sense that, as one colleague put it, the Jackal is forever going out dancing to “Olivier’s favorite music,” Carlos evokes the intense craziness of the era itself. This period piece has immediacy and, in fact, the anachronisms promote it.

The most contemporary thing about Carlos is its authentic sense that the nation-state is in some ways helpless. Carlos’ 20-odd-year run was enabled by the complicity (and incompetence) of many, many governments. His career like the movie, was an international coproduction.

Born in 1949, the son of a wealthy Marxist lawyer who named him after the architect of the Russian Revolution and would send him to study at Moscow’s international Lumumba University, Ilich Ramírez Sánchez followed a path that was nothing if not overdetermined.

The young Ilich may not have trained, as some imagined, in Cuba, but there was no need. During his adolescence, his native Venezuela was the very cradle of the urban terrorism that would subsequently spread throughout Latin America and then the world. Jailed since 1997, Carlos remains a local hero; Hugo Chavez, a pen pal for over a decade, last year hailed him as “a revolutionary fighter.”

Expelled from Lumumba U for his unruly attitude, Carlos did dream of becoming another Che, and made his way to Amman to join the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. He was given his nom de guerre and wounded during “Black September” in 1970, and thereafter joined his indulgent mother in London to resume his studies at the London School of Economics. This is all back story for Assayas. When we meet him, 24-year-old Carlos is already in the life.

Spanning 20 years, Carlos opens in June 1973 (more or less mid Munich in the Palestinian-Israeli war of terror-counterterror) with Mossad agents taking out the PFLP’s chief European agent Mohammed Boudia; the movie then jumps from Paris to Beirut, where PFLP co-founder Wadi Haddad, who frequently used foreign nationals, mainly Japanese and West German militants, for his international operations, appoints Carlos assistant to Boudia’s successor. Onto London, where his first solo operation is shooting the Jewish head of Marks & Spencer in the face.

Part I follows Carlos around Western Europe as he organizes a series of not always successful bombings and airport attacks, then makes his bones by shooting his way out of a Latin Quarter party full of guitar-strumming Latin American lefties, gunning down two (unarmed) French secret policemen and a PFLP snitch point blank. Reporting on the Rue Tollier massacre, next morning’s Libération ran the headline “MATCH CARLOS 3-O.” His pseudonym in the papers! Now in Yemen, his mentor Haddad (Lebanese actor Ahmad Kaabour) disapproves: “You have become a star for the Western media.”

Let the name dropping begin. Word comes that Saddam Hussein, who got his start as a Baath party hit man, is impressed with Carlos and requests that he head up an operation he’s bankrolling to hijack the upcoming OPEC summit meeting in Vienna and punish America’s Middle Eastern allies by executing the Saudi and Iranian oil ministers. Part I ends with Carlos and his posse, dressed like Black Panthers (leather jackets, berets, shades) and carrying their weapons in gym bags, setting off down the Ringstrasse to storm the Texaco Building.

The extended treatment of the OPEC mission that takes up much of Part II would make a terrific movie in its own right.

After a lengthy shootout, Carlos and his gang, notably the German cop killer code-named Nada(Julia Hummer), take control and step back, and the teams showboat leader preens and postures on the world stage—most famously the tarmac of the Algiers airport.

Carlos’s 20-odd-year run was enabled by the complicity (and incompetence) of many, many governments. His career, like the movie, was an international co-production.

In Assayas’ account, Carlos bonds with some of his captives and threatens others, makes extravagant demands on the Austrians, and generally gives his greatest performance. (Assayas can’t resist having one of the lesser oil ministers request an autograph.) The sequence is also a great directorial performance, a multistage rocket with an explosive takeoff, a period of sustained tension dropping away in favor of fascinated horror and grotesque humor as Carlos manages to get his show aloft and bound for North Africa.

Carlos is privy to the nature of the mission although, back in the day, the world was dumbfounded. (“The terrorists seemed to have only a hazy notion of what they intended to achieve,” Walter Laqueur would write. “They induced Austrian radio to broadcast the text of an ideological statement which, dealing with an obscure topic and formulated in leftwing sectarian language, might just as well have been read out in Chinese ...”) This daring stunt dominated headlines for several days before Christmas 1975 and became a nonevent—or rather, an event named “Carlos” for whom, bribed by Libya to return the Saudi and Iranian ministers, the caper was a massive payday both in terms of money and notoriety.

Thus Carlos entered the dream life; he was now Carlos the Jackal. The nickname, never used in the Assayas film, came when British police found, in what they assumed were Carlos’ belongings, a paperback copy of The Day of the Jackal, Frederick Forsyth’s 1971 bestseller about a plot to assassinate French President Charles de Gaulle. But Carlos’ emergence as an international star coincided almost exactly with the widespread popularity of the Thomas Harris thriller Black Sunday.

A vision of pro-Palestinian terrorists hijacking the Goodyear blimp in order to bomb the Super Bowl in Miami and obliterate 80,000 fans including the president of the United States, Black Sunday was published the same month as Carlos’ Rue Toullier shootout. By the time John Frankenheimer’s movie version appeared in April 1977, “the most celebrated and sought after terrorist abroad today” was the subject of an English-language biography with “all the ingredients of a fictional espionage novel” per The New York Times. (“It’s a wonder that he didn’t wear a T-shirt with ’I am a terrorist,’ stenciled across the front,” one of Carlos’ acquaintances told the author, Colin Smith.)

Heralded by an incongruous bit of nouveau Hawaiian music as he returns to Yemen, Carlos finds a grim-faced Haddad. As punishment for reneging on the OPEC contract, Haddad takes him on the next big job, hijacking a Tel Aviv-bound Air France Airbus to Uganda. Lucky break, as it turns out. The German radicals Haddad used in place of Carlos were killed by Israeli commandos at Entebbe. When the press eagerly credits him as the hijacking’s mastermind, Carlos is outraged and self-righteously quits the PFLP: “I won’t go on with them, my brand image suffers from it too much!”

The “jet-set terrorist,” as one former associate would call him, goes into business for himself. Carlos lines up a new backer, Syria, and gets himself a partner with Stasi connections—Johannes Heinrich (lanky Alexander Scheer), bookstore-owning co-founder of West Germany’s Revolutionary Cells. He even takes a wife. Part II ends with Carlos seducing Heinrich’s girlfriend, the ultra-sulky revolutionary feminist vixen Magdalena Kopp (Nora von Waldstatten in a supermodel-making performance). Business seems promising: Colonel Qaddafi (and, so the movie suggests, Soviet spy master Yuri Andropov) award Carlos and Heinrich the contract on Egyptian President Anwar Sadat.

In Part III, the Jackal appears as the de facto king of Budapest, ensconced in a Rfizsadomb villa, using the local cops for target practice, throwing himself a birthday bash at the Grand Hotel on Margitsziget (and thus allowing Assayas his requisite party scene). For excitement, Carlos carouses in East Berlin with Stasi-agent hookers and contemplates blowing up Radio Free Europe on behalf of Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu. His sense of omnipotence suffers when a rival outfit beats him to the Sadat hit, but when Magda gets busted in France, he orchestrates a petulant, if deadly, series of retaliatory bombings—mildly Carlossal.

Meanwhile, the legend grew. An obscure 1979 Mexican cheapster, Carlos el Terrorista, anticipated Carlos’ 1980s domesticity. Seeking to go straight, the world famous terrorist kills his Mafia(!) handler and tries to cut a deal with the CIA; the agency then double-crosses him by abducting and holding his wife and daughter for ransom. More famously, Carlos would appear as the arch villain of Robert Ludlum’s 1980s Bourne trilogy. The new secret agent of history, he’s credited with even masterminding the Kennedy assassination—as a 14-year-old Caracas schoolboy!

In 1989, the Berlin Wall comes down, and Carlos’ racket falls apart. “Things have changed,” his Syrian patron hisses. Having already lost his East European bases to perestroika, Carlos is kicked out of Damascus and pingponged around the Arab world until he finally finds refuge, sans Magda and their child, in Sudan. The movie ends on a definite diminuendo with the overweight playboy contemplating liposuction and then getting fingered dancing the frug with his final concubine at the last disco in Khartoum. Carlos is kidnapped and returned to France to stand trial for the Rue Toullier shootings 20 years earlier.

Brought to justice, Carlos became an even more fantastic creature. His capture was fictionalized in The Assignment (1997), with Aidan Quinn playing both the terrorist and his CIA-trained double; the Bruce Willis vehicle The Jackal (a remake of the 1973 Day of the Jackal, by now widely assumed to have been inspired by Carlos) was released shortly after British journalist John Holloin published a new Carlos biography in 1998; the same year, Carlos had a cameo role in Tom Clancy’s 1998 novel Rainbow Six; and in The Last Inauguration by Charles Lichtman, he is hired by Saddam Hussein to wipe out the entire U.S. government by sabotaging the inaugural ball, and was either the arch villain or, according to one reviewer, “the most appealingcharacter.”

Then came 9/11 and, like guerrilla warfare, old-school terrorism was obsolete.

It’s hardly surprising that political terrorism would be a major preoccupation of the past decade, although it may be sometime before anyone devotes a three-part saga to the life of Osama bin Laden.

Only a few small movies, notably Hany Abu-Assad’i Paradise Now, Julia Loktev’s Day Night Day Night, and Paul Greengrass’ United 93 have pondered the nature of contemporary terrorism. Meanwhile, the ghosts of bombings past have paraded across the screen. Two American documentaries, The Weather Underground and Guerrilla: The Taking of Patty Hearst, initiated the cycle, as did a revived interest in The Battle of Algiers among Pentagon theorists and cinephiles alike. Steven Spielberg’s Munich planted Hollywood’s flag; the cycle then went international with Koji Wakamatsu’s United Red Army, Uli Edel’s The Baader Meinhof Complex, and Barbet Schroeder’s Terror’s Advocate, a documentary portrait of rogue lawyer Jacques Verges, which devotes a substantial amount of time to Carlos and even features the still-stylish Magda in a supporting role.

For all their mayhem, these movies, like Carlos, provide an odd sort of comfort. However crazy, misguided or evil, 1970s terrorists had a comprehensible rationale and even a social agenda. The fanatics of the aughts are far more frightening, and not just because suicide bombings are a near-daily occurrence in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, or because the combined body count produced by Baader-Meinhof, the United Red Army, the Symbionese Liberation Army, and Carlos was considerably less than the 3,000 casualties reaped by al-Qaida in a single day.

The conventional wisdom of the 1970s held that urban terrorism was incapable of effecting political change and remarkable mainly for the attention paid to it. “Terrorism ultimately aims at the spectator,” psychiatrist F. Gentry Harris told the U.S. Congress in hearings held in early 1974, at precisely the time that Patty Hearst was captive to the SLA, and Carlos chucked a bomb into the London branch of an Israeli bank. “The victim is secondary. The terrorist cannot act in a vacuum. He needs an audience to observe his actions.” The generational audience is inscribed when the giddy Baader Meinhof opens with a plaintive Janis Joplin fanfare, while the more downbeat Munich features a key sequence founded on the universality of Motown.

Carlos taps into an even more active nostalgia. Watching this bizarre saga, it is difficult not to tsk-tsk the amazing innocence of the pre-9/11 world—the astounding absence of embassy security, the incredible possibility that militant crazies might simply bring their rocket launchers to the airport and attempt to blow up El Al planes on the runway. This appreciation of disorder is something quite different from a yearning for lost ideals (Carlos has none), although, as an epic docudrama constructed around a dangerously dashing Latin lover of action, Carlos has been inevitably bracketed with Steven Soderbergh’s Che.

Carlos and Che are both technical achievements but the filmmaking is quite different. Soderbergh engages Rossellini; Assayas is closer to Fritz Lang. (As Les Vampires was to Irma Vep, so Dr. Mabuse is to Carlos.) Soderbergh’s protagonist is a martyred saint; Assayas’ is a publicity-seeking celebrity. Where Che is high-minded, emotionally distant, and ascetic, Carlos is low-down, up close, and sensationalist. This is as it should be. Despite his jaunty beret and taste for Cuban cigars, Carlos was the anti-Che; in Castro’s Cuba, the “urban terrorism” that came to supersede guerrilla warfare was, in fact, a derogatory term.

As cinema, Che aspires to be an objective meditation on the process of “making history.” Less rigorous and more fun, Carlos is an outrageous political gangster film, full of cheap thrills and unburdened by even a hint of German philosophy. (In France, it was more often compared to the saga of another media-manipulating 1970s criminal, Jean-Francois Richet’s two-part, 4-hour-plus Mesrine, with Vincent Cassel as France’s public enemy No. 1.) Carlos’ interest is less in making history than simply making up his story. The latest and the longest cine-spectacularization of 1970s terrorism made since 9/11 changed the world, Carlos pays relatively little attention to terror’s casualties. They are, after all, collateral damage sacrifices on the altar of celebrity.

As much as any reality TV hopeful, Carlos’ true interest is fame. Bustling around the world on a perpetual adrenaline high, suitcases full of firearms and pockets stuffed with fake passports—confidently arrogant yet desperate for approval—Carlos is a show business hyphenate, a would-be producer-director, the wannabe star of a self-authored scenario. (Even in jail, he attempted to sue Assayas’ producers for the right of final cut.) The only difference: His bombs really were bombs.

J. Hoberman was the longtime Village Voice film critic. He is the author, co-author, or editor of 12 books, including Bridge of Light: Yiddish Film Between Two Worlds and, with Jeffrey Shandler, Entertaining America: Jews, Movies, and Broadcasting.