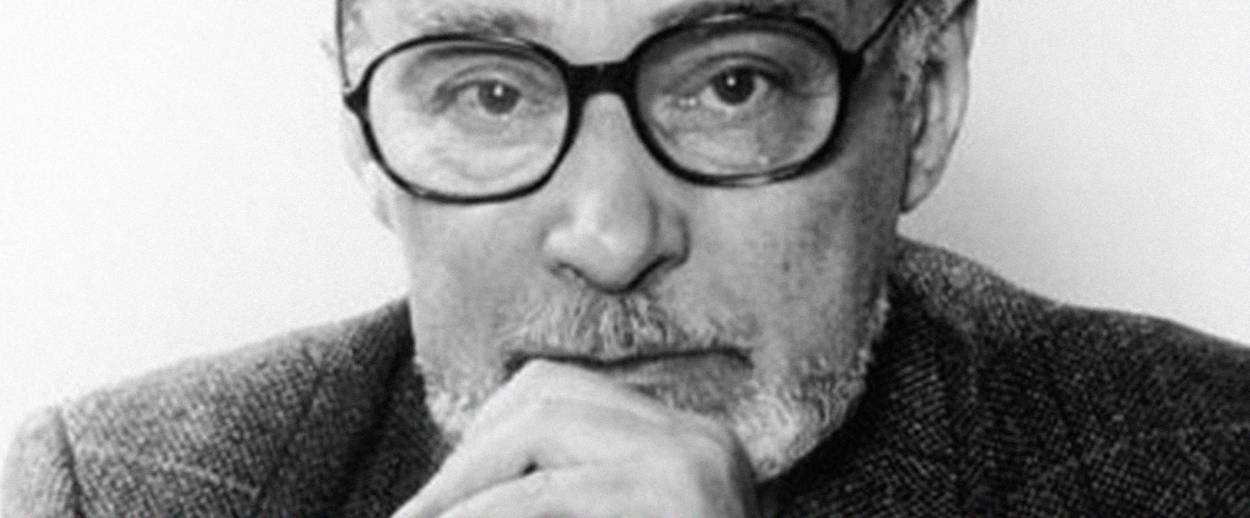

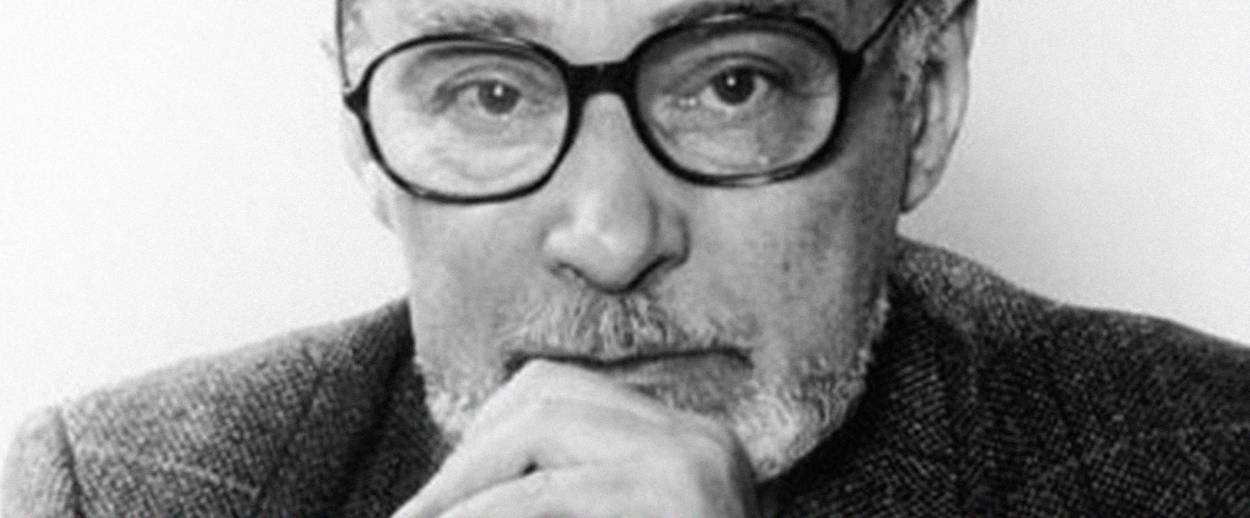

Primo Levi’s Christmas in Auschwitz

The chemist and writer recalls the last holiday before liberation

Italian chemist and writer Primo Levi was imprisoned in Monowitz, one of the three subcamps of Auschwitz (also known as Auschwitz III), for 11 months before the concentration camp was liberated on January 18, 1945. In the January 30, 1986 issue of the New York Review of Books, a little over a year before he died, Levi recounted his memories of Christmas 1944, when prisoners at Monowitz—many of whom had technical skills and worked in factories outside the camp—knew the Russian army was advancing on the Germans. (“At night, when all the noises of the Camp had died down,” he wrote, “we heard the thunder of the artillery coming closer and closer.”)

Though they understood the war may soon be ending, Levi and his fellow prisoners knew nothing of their fate. So as December wore on and snow engulfed the camp and the factory where Levi worked, things both had changed and were the same as always. Until Christmas:

It was a memorable Christmas for the world at war; memorable for me too, because it was marked by a miracle. At Auschwitz, the various categories of prisoners (political, common criminals, social misfits, homosexuals, etc.) were allowed to receive gift packages from home, but not the Jews. Anyway, from whom could the Jews have received them? From their families, exterminated or confined in the surviving ghettos? From the very few who had escaped the roundups, hidden in cellars, in attics, terrified and penniless? And who knew our address? For all the world knew, we were dead.

And yet a package did finally find its way to me, through a chain of friends, sent by my sister and my mother, who were hidden in Italy. The last link of that chain was Lorenzo Perrone, the bricklayer from Fossano, of whom I have spoken in Survival in Auschwitz, and whose heartbreaking end I have recounted here in “Lorenzo’s Return.”* The package contained ersatz chocolate, cookies, and powdered milk, but to describe its real value, the impact it had on me and on my friend Alberto, is beyond the powers of ordinary language. In the Camp, the terms eating, food, hunger had meanings totally different from their usual ones. That unexpected, improbable, impossible package was like a meteorite, a heavenly object, charged with symbols, immensely precious, and with an enormous momentum.

You can read the rest of Levi’s essay here.

Related: 101 Great Jewish Books: Survival in Auschwitz, Primo Levi (1947)

Higher Truth

Exceptional Spiritedness

Stephanie Butnick is chief strategy officer of Tablet Magazine, co-founder of Tablet Studios, and a host of the Unorthodox podcast.