“What am I going to say to mom?” Lin asked her sister Martha. It was 1987, and Lin and her husband Peter had decided to adopt a black baby. A sculptor who carves and assembles wooden knots, bridges, and ladders, Lin was raised in an open-minded secular Jewish home. But she wasn’t certain how her mother would react to the prospect of having a black grandchild. “Tell her about adoption first,” Martha advised. “Give her a couple of weeks to let it sink in, and then talk to her about race.”

A short, wiry woman with untamed curly hair, Lin remembers calling her mother. “We’re going to adopt children but it will take a while.” Her mother’s response surprised her. “Not if you adopt black children!”

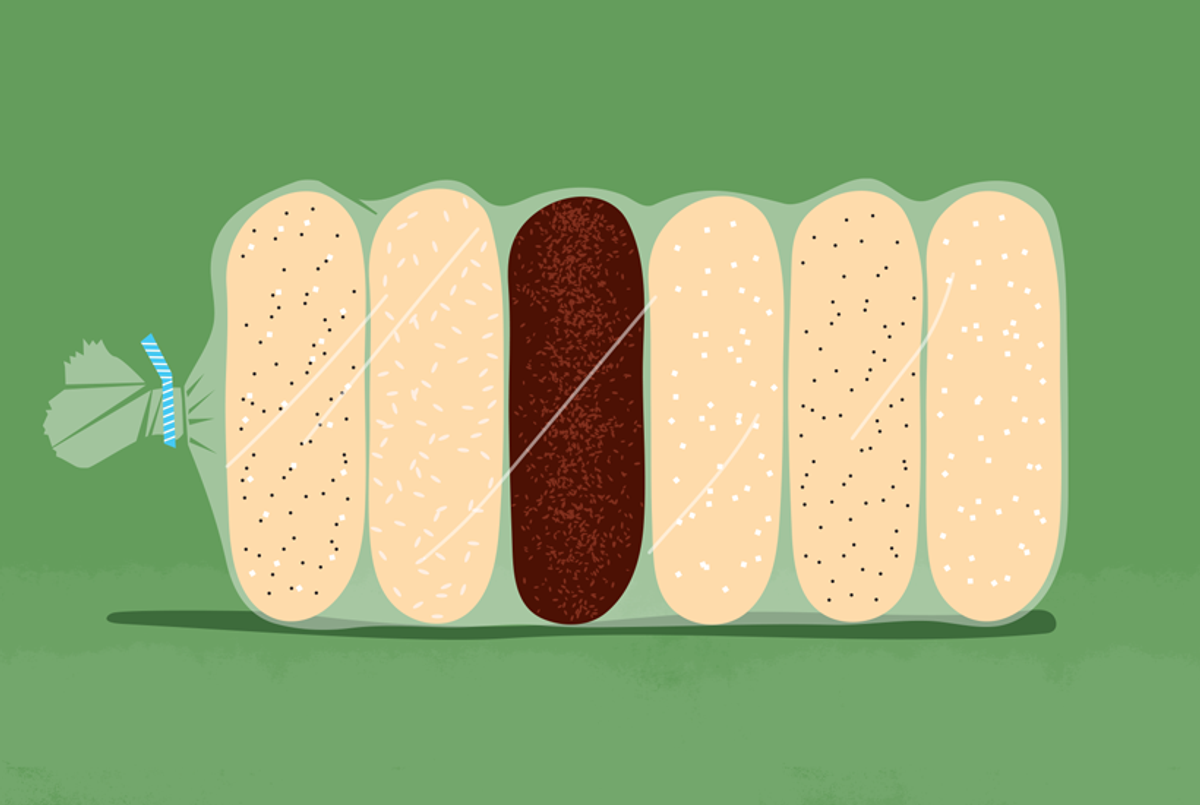

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, two-thirds of adopted children belong to racial minorities. While there aren’t any government statistics that speak to the religious identity of adoptive parents, 70 percent of the Jewish respondents to a recent survey adopted children of a different race (compared to an average of 40 percent). All four sisters in Lin’s family save the youngest had had reproductive problems as a result of their mother’s treatment with DES (diethylstilbestrol), a synthetic estrogen that was given to pregnant women between 1940 and 1971 in the erroneous belief that it would reduce pregnancy complications. Martha died of cancer related to DES exposure a couple of months before Lin’s new baby arrived at the airport in Bangor, Maine, on March 7, 1988.

He was charming, easy-going, active and bright. “He had a six-pack at three months,” Lin says, laughing. Her mother often wondered whether the adoption agency had gotten his birth date wrong, because he seemed several months older than the papers stated. The infant’s birth mother, who had been adopted herself, was only 13. She was half black and half Japanese; the boy’s 15-year-old birth father was half black and half white. The mixed-race baby had been labeled “undesirable,” languishing in a Florida foster home for three months where he was given the name Sam, from Samurai, because of his faintly slanted eyes. Peter and Lin decided to name him Max, after Peter’s grandfather. “Max raided the self-confidence store,” is one of the first things Lin tells me about her son. “Nobody got any of it. He got it all.”

To Lin and Peter it didn’t matter what color their kids were. Bespectacled and bald with an impish gleam in his eyes, Peter would look in the mirror and think, “Man, you’re looking pale today!” Other, white children often looked sick to him. It always struck him as odd when people said, “You’re sooo good to have adopted that baby!” His wife’s response was, “Hey, we wanted kids. They were sooo good to exist.”

***

The practice of transracial adoptions has long sparked criticism from both African American and Caucasian individuals and institutions. In the 1970s, the National Association of Black Social Workers (NABSW) issued a statement publicly opposing transracial adoptions. It worried that being raised in a white family would compromise African American children’s racial and cultural identity and prevent them from developing coping strategies to deal with discrimination. NABSW eventually condoned the adoption of black children by white parents, if black adoptive parents couldn’t be found, but its concerns still reverberate today.

Lin and Peter’s family—among others—suggests that members of functional transracial families do not feel alienated among themselves; it is the way the public perceives and treats them that makes them feel ostracized. Even if nothing bad has ever happened to them in person, a certain amount of paranoia is inevitable. One time when Max was about 3 and threw a tantrum in a public place, Lin pulled him by his arm toward the car. A man walked up to them. Suddenly aware of their racial differences, she feared the stranger was thinking she had kidnapped a little black boy.

“You do what the lady tells you!” The man shouted at Max, who stopped crying instantly. “Why do you let the man talk to you like that?” He asked his mother, who was speechless. “It surprised me just as much as it surprised you,” Lin told him.

Peter had also wondered how his family would react to his decision to adopt black children—and he was equally surprised when they didn’t blink. His grandparents had emigrated from Eastern Europe, and Peter grew up in a diverse working-class neighborhood outside of Boston surrounded by his conservative Jewish family. His parents were founding members of the neighborhood’s temple, but, he says, for him being Jewish has always been more of a cultural identity than a religious one. The High Holidays and Hanukkah were celebrated but the family didn’t observe Shabbat. “It was one of those funny clubs you belong to that you never know you belong to,” he says. “We have years of shared history. A lot of persecution, a lot of hard times. That was closer to us than we really understood.”

Calling himself an atheist Jew, Peter has made efforts to pass on his Jewish values to his adopted children. Now in his 60s, Peter has gone from owning a musical instrument store to working as a home inspector and, more recently, a real-estate developer. He wanted his children to care about other people, to be honest, and to appreciate family and education.

Max’s little sister arrived three months after he turned 3. Like Max’s, her adoption story was told every year when the family celebrated “adoption day.” Hers was all about transportation. Peter, Lin, and Max took a car, a plane, a train, a bus, a subway, and a taxi to pick up the 3-week-old girl from Washington, D.C. Then they reversed the whole thing. By the time they were on the plane back to Maine, the big-cheeked baby girl had fallen asleep in her car seat. When she woke up, the flight attendants were stunned that she was real. They had mistaken her for a Cabbage Patch Doll. “We thought it was odd that you had your little boy’s doll strapped in a car seat,” one of them said. The couple named their new child Thea, after Lin’s father.

It was clear right from the start that Thea was different from Max. A shy and introverted child, “she was a little slower to walk and a little slower to talk,” Peter says. “She always got there but it took a little more time.” Thea is “a very hard worker,” more patient than Max and more focused. She has never asked as many questions as her brother, and to this day seems far more cautious and reserved when approached by strangers.

***

Peter and Lin raised their children in a house in the woods at the end of a dead-end street outside of Portland, Maine. Peter had never been an athlete, but Max was obsessed with sports. He played soccer and basketball, and his track team won the state championship. “You get to know things that you have never done before. It was fun,” Peter says, mentioning his and Lin’s surprise when Thea decided to become a cheerleader. “Yikes. That was the last thing I would have thought was fun. Well, she didn’t want to play the banjo like I did. So, you change your expectations. Sometimes [biological] kids are just carbon copies of their parents. I always thought that was creepy.” On the plus side, he adds, “Both of my kids put more effort into their education than I ever did.”

Both Max and Thea went to schools that were 99 percent white and Christian. The family agrees that most teachers were terrific, but there certainly were exceptions. When Max was in kindergarten, Lin asked the teacher to add pictures of black children on the wall. “I’ve never had a black child before!” the teacher said helplessly. “You know,” Lin responded matter-of-factly, “their minds work the same way.” In the same vein, Lin came to school to talk to Max’s class about Hanukkah. But after that, the daily Christmas craze continued unabated. Lin returned, requesting the teacher give Hanukkah a more prominent role. “You already had your holiday!” the teacher responded arrogantly. The incident has burned itself into the family’s collective history. “That was the first time that I was like, I am different,” Max says. “I already knew [I was different] visually but didn’t realize that no one celebrates Hanukkah, except for me. At least in my town, that small world.”

‘If you have a problem with my color, it’s your problem.’

When she was little being Jewish made Thea feel special. Compared to Max’s kindergarten teacher, hers was magnificent. In elementary school, Thea enjoyed teaching her class about Hanukkah, feeling like an ambassador of Judaism. At the same time, she was conflicted. She felt she missed out on Christmas and wasn’t getting what the other kids got. Max felt similarly, and when Hanukkah fell on Christmas Day, he asked his parents to give him his presents that day. Lin, whose great-grandparents had emigrated from Germany, had grown up in a family that was keen to assimilate. They celebrated Christmas, and Lin would have possibly continued this tradition with her children, but Peter was adamant. Being Jewish, he tells me, is as much about the things one does and believes in as it is about the things one doesn’t believe in or do.

Apart from having Chinese food and going to the movies, watching basketball became part of the family’s “Christmas” tradition. “I saw black people on TV and I understood that black people can rap and play basketball,” Max remembers. “And I can play basketball, so I was like ‘Cool!’ But there were no Jewish media personalities that I was aware of that fit any stereotypes.” So, when his classmates said things like “Stop being so Jewish!” Max didn’t even know what they meant. He thought it was funny when his grandfather spoke Yiddish during the family’s extravagant holiday celebrations, but he lacked the context to understand how Jews were perceived by others. Through his classmates’ vernacular, he says, he learned about common Jewish stereotypes, such as stinginess.

Eager to pass on a mixed heritage that wasn’t theirs, Lin and Peter filled their home with art from all over the world and books that featured African American, Asian, and Native American characters. Today, they berate themselves for “not doing enough African American things” with their children. And maybe they should have taken them to temple? “But I didn’t want to take them to another all-white world,” Lin says now. “If we were to take them to another organized thing it would have had to be around people of color.”

Every other week, the family went to an interracial adoption support group in Portland. From other families they learned about African American hair and skincare—and about parental expectations. “With biological children you expect that they are going to have at least some of your traits,” Peter tells me. “With kids that are not sprung from your loins, you need to think about your expectations differently.”

Max and Thea don’t have the fondest memories of the adoption support group. “I didn’t like any of those kids,” Max tells me at a Starbucks in the East Village. The 26-year-old is an account executive at a digital marketing agency in Manhattan and switches easily from goofy and soft to serious and opinionated. “We’d tear around town on our bikes, and these kids [in the adoption group] would cry and talk to their moms when they fell off something. And I was like, ‘Keep going!’ ” Later, when his father suggested he become friends with another black boy, he responded, “I don’t really like that kid. Why would I make friends with him just because he’s black?”

Thea also didn’t seem to get much out of the adoption group. “I don’t think I was very interested in African American culture,” the 23-year-old nurse, who recently started working in a children’s hospital in Cincinnati, tells me. “I didn’t want to be different. Like being brought into that [group] made me feel even less like a part of that town.” For Thea, there were already too many things that made her different. Being black, Jewish, and adopted never was a problem within her tight-knit family, but outside of it, it often forced her to over-share. One question quickly leads to the next, and Thea never liked it when strangers pried into her private life. “How much did you weigh when you were born?” is just one of those questions. “I don’t know,” Thea would respond. “Why not?” “Because I was adopted.”

***

Thea and Max knew early on that Lin and Peter weren’t their biological parents. From preschool on Max would look around and think, “There are 50 people in my life and not a single one looks like me.” Thea, on the other hand, didn’t really think about those differences, until that one day when she was 7 or 8. Another child refused to play with her because she was black. Thea told her parents who promptly went to the principal. The principal left a message on the girl’s parents’ answering machine, which, Lin says, was “the wrong thing to do.” The girl was reprimanded, and her relatives, whom Lin and Peter had been friendly with, stopped speaking to them.

There was really no way of knowing how to deal with society’s various forms of racism and ignorance. Neither Lin nor Peter were ever mocked for their skin color or religion, so they “invented” their responses as they went along. One day Max came home reporting that a kid in school had yelled at him, “Your skin is the color of poop!” He remembers, “We were all talking trash. I was probably yelling terrible things at him. And our team was losing, so I was mad.” Lin and Peter called in a meeting with the principal and the kid, which, Max says, ruined any potential for friendship with this boy. “So I regret telling my parents. There were other incidents after that but none that I actually told anyone about. For the most part, I was happy to take care of things on my own. I had a ton of friends who had my back.” Lin adds that while Thea felt uncomfortable being in such a white community and was easily hurt, Max’s response soon became, “If you have a problem with my color, it’s your problem.”

Still, questions about Max’s race kept arising. One time his basketball teammates told him that the reason he could jump so high is that black people have an extra muscle in their legs. The assumption that he has a big penis because he is black was ubiquitous among his male and female friends. His response was forgiving and jokey. “Wanna find out?” he’d say.

Thea seems to have experienced less racism from classmates than Max, who had already paved the way for his younger sister. Combing her shiny black hair with her fingers, she tells me that it was her high-school history teacher whom she associates with her most lingering racist experience. One time he claimed that it is safe to assume that all the ancestors of his students had come through Ellis Island. Another time a kid in class announced that President Obama had ordered all whites to the cotton fields. When the history teacher cracked up, Thea said, “I don’t think that’s funny.” The teacher told her to “lighten up.”

Eager to fit in, Thea did what she could. To her parents’ (initial) dismay, she insisted on getting her hair straightened when she was 12 or 13. In high school she formed tight friendships that have lasted to this day. “Thea used to say, ‘Oh, I’m just a white girl with brown skin,’ “ Lin tells me. “And I’d say, ‘No, you’re a black middle-class girl.’ ” To this day, it confuses Thea when people mistake her for a tough, inner-city girl or ask for her music preferences only to exclaim, “Oh, you like white people’s music!”

Peter says that those “silly things” weren’t the norm and that he worried more about the quieter kind of racism that no one admits to. He and Lin tried their best to prepare their children for a world that is unsympathetic toward people who are different. Lin jokes that she made friends with the parents of “the niftiest white girl in Max’s class,” so their daughter wouldn’t turn down her son for a date. She also begged Max to tell her if he was ever turned down by a girl because of his race. She’d talk to the girl’s parents and straighten things out. “I carried that with me almost through high school, second-guessing girls that I liked,” Max says. When he was 12, Lin assured him that it would be OK with her if he were gay. He responded, “I am already black and Jewish.” (“And don’t forget adopted,” Peter chimed in.)

***

After high school Max went to college in Pennsylvania. There were many Jews among his classmates, and he liked joining them at the Hillel house and lighting candles with them on Hanukkah. Two of them became his best friends, and last May, the three young men embarked on a Birthright trip to Israel together. “Everyone was very hospitable,” Max remembers. “And learning about all the history of the Jewish people was fascinating.” He quickly bonded with and admired the soldiers who were assigned to take care of the group. After the trip, he moved in with his two friends.

When the discussion of interracial and -religious marriage came up on the Birthright trip, the only other person of color sat in a corner sobbing. She had just recounted how someone had called her a “nigger.” Max, who is dating a white, non-Jewish girl, felt like it was time to stand up for his principles. “I don’t believe in it at all,” he told his fellow Jews about racial and religious purity. “If it is your choice that you only want to date Jewish people, OK. I just don’t believe it should be enforced on anyone. I think you’re short-sighting yourself. If you’re romantic enough to believe in one true love, you should give everyone a fair shot because what if you miss?”

Max tells me that unlike his parents, he’d never raise his children in a homogeneous area. While he does want to pass on his Jewish values and intends to practice Judaism for his entire life, he would never run the risk that his children might become the same kids that once taunted him. “I want them to understand that there are people who do different things. Christmas isn’t normal, Hanukkah isn’t normal, black isn’t normal, white isn’t normal.” Asked whether there was anything positive about being the only black Jewish child in his school he tells me that he “trained” his friends to not use the word “nigger” all the time. “A lot of the kids in my high school were [using it]. But the kids that were close to me weren’t. And they’re not saying, ‘That’s so Jewish,’ because they’re friends with me.”

Peter and Lin question their decision to raise their children in white suburbia. When they sent them off to college, Peter worried about how they’d weather the outside world without the “beloved disconnect” they grew up with. “[In Maine] they were attached to us. They weren’t purely African American. Everybody knew they were Peter and Lin’s kids.” This, he says, offered protection—a protection they lost once they left the nest.

As he toured the country with Thea in search of a good nursing school, Peter was struck by how present 400 years of slavery remain. He could see it everywhere, in the sad-looking faces of blacks waiting for buses in Richmond, Virginia, and in the TV reports of young black men being stopped and frisked. He and his wife had done what they could, always standing up for their children and preparing Max for a world that is hostile toward young black males. But his kids had adopted, Peter says, a sense of white privilege. And he wasn’t sure whether this protected them from harassment or hurt them. Max has been pulled over by police more than a dozen times, even though he hadn’t done anything wrong. He is frequently followed by clerks who suspect him of shoplifting. But, for the most part, he doesn’t tell his parents about these incidents. “I just chalk it up as ignorance and let it go.”

When Thea decided to attend a Jesuit college in New England, Peter’s first response was, “Oh my God, what am I doing, sending my little Jewish girl off to a Jesuit college? This is crazy!” He toured the college with Thea and quickly came around: The values of the Jesuits—their commitment to public service and education, for example—weren’t much different from his Jewish values. I asked Thea what role Judaism plays for her today. While Max embraces his Jewish roots, Thea remains hesitant. She enjoys celebrating Christmas with her friends.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that when racial and religious categories fail to define one’s identity, geographic place becomes the next best thing. When I asked Thea about her strongest cultural, ethnic or religious ties, her immediate response was “Maine!” Like her parents, Thea loves nature and admires the Mainers for being non-materialistic, hard workers. Max, too, mentions Maine first. “Go visit my state!” he likes to tell people. “You’ll love it!”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Sabine Heinlein is the author of the IPPY Gold Award-winning narrative nonfiction book Among Murderers: Life After Prison and the ebook The Orphan Zoo: Rise and Fall of the Farm at Creedmoor Psychiatric Center. She is a recipient of the Pushcart Prize.

Sabine Heinlein is the author of the IPPY Gold Award-winning narrative nonfiction book Among Murderers: Life After Prison and the ebook The Orphan Zoo: Rise and Fall of the Farm at Creedmoor Psychiatric Center. She is a recipient of the Pushcart Prize.