The Middle Eastern nation of Qatar has a population consisting of a little more than 300,000 native Qataris, living in 11,586 square kilometers of mostly empty sand. Thus, Qatar might seem to be an unlikely fulcrum for reshaping Western politics and culture through policy debates, think tanks, universities and brand-name cultural institutions. Yet over the past decade, Qatar has implemented the single most sophisticated, sustained, successful effort by any foreign nation or interest group to shape Western policymaking–especially American opinion—in its favor.

The amount of money that Qatar has poured into local governments, universities, schools, educational organizations, think tanks, and media across America, and the number of instruments and initiatives, like the anti-Israel Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement, that Qatar uses to influence American opinion, is nearly overwhelming. It is impossible to understand how Washington works today without understanding the nature and scope of Qatar’s campaign.

Qatar has already turned much of its energy wealth into an enviable investment portfolio with significant holdings throughout the United States. Its strategy of using sovereign wealth funds and other investment vehicles as political instruments, for example, makes old-fashioned influence plays like bundling $1,000 campaign contributions to political candidates or placing op-eds by retired foreign service officers in the Washington Post seem the equivalent of writing fundraising letters by hand. Last year alone, Qatar reported $2.8 billion in direct foreign investment in American companies, much of which was targeted at states like South Carolina, where Doha took a big space in the state’s aerospace and drone industry. South Carolina’s elected representatives exercise substantial influence on the congressional committees responsible for overseeing U.S. foreign relations and defense expenditures. South Carolina’s influential senior senator, Lindsey Graham, has called for a resolution to the crisis pitting Qatar against its neighbors Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, but has frequently proven to be an outspoken public critic of Qatar’s main target, Saudi crown prince and de facto ruler Mohammed bin Salman.

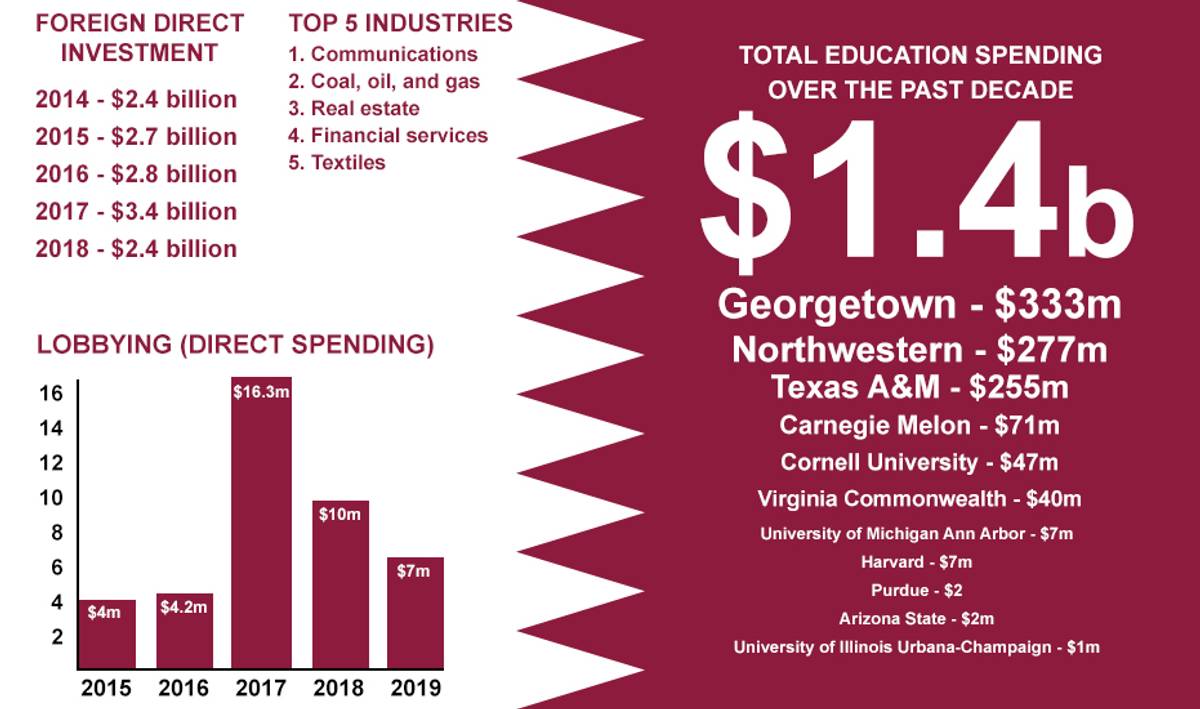

Only a small percentage of Qatar’s jaw-dropping expenditures in America go toward gaming the loyalties of politicians, though. In a broader sense, the kingdom’s influence-buying strategies are a textbook example of how to transform cash into “soft” power in an era in which once-independent American institutions like the prestige media have been replaced by much flatter and easily gamed tech platforms powered by partisan alignments funded by large sums of corporate and foreign cash. Qatar’s official efforts to lobby the U.S. government quadrupled between 2016-2017, from $4.2 million to $16.3 million, but that pales in comparison to the cost of the indirect investments in U.S. political culture. Over an eight-year period from 2009-2017, The Qatar Foundation gave $30.6 million to dozens of American K-12 and public high schools—a pittance compared to the more than one billion dollars the country gave to U.S. universities between 2011-2017, making it “the largest foreign funder by far,” of American academia according to the nonpartisan watchdog group,Project On Government Oversight (POGO). In fact, according to POGO Qatar was the “only country to give over $1 billion in the seven years covered by the Higher Education Act data” included in the group’s report—the next biggest foreign spender, England, was more than $200 million behind. A final example from a Congressional Research Service report updated in March of this year notes that in “January 2018 U.S.-Qatar Strategic Dialogue “recognized” QIA’s commitment of $45 billion in future investments in U.S. companies and real estate.”

In addition to being exponentially more expensive, Qatar’s soft-power strategies are also infinitely more sophisticated than their predecessors. To understand how the new influence system works, imagine a museum hall that has been emptied of all the artworks or antiquities that visitors once agreed were valuable. That empty space is the American public sphere, which was once populated by institutions whose financial independence and professional norms allowed them to reinforce each other in validating accounts of reality for large numbers of people.

Now that those institutions have adopted openly partisan alignments and toxic conspiracy theorizing as the source of their incomes, they are no longer capable of creating a reality that large numbers of people can agree on. The only way to obtain even fleeting agreement in such a decayed and mercenary system is to buy it, in multiple places at once–left, right, center, academia, think tanks, political players, law firms, prestige media brands, leading politicians–so that each piece of the shattered mirror seems to reflect a common agreed upon reality. The difficulty of that task, of course, is that the illusions thus created are both fleeting and expensive. Qatar provides a textbook example of how to play that game, for those whose pockets are deep enough.

“It’s a tiny place with very significant resources,” says Princeton scholar of the Middle East Bernard Haykel. “The Qataris want to protect themselves and make themselves indispensable. They do that in part by making Qatar a convening venue. For instance, if the United States wants to deal with the Taliban, they go through Doha.”

At the end of last month, Taliban and U.S. officials signed an agreement that would allow U.S. forces to withdraw finally from Afghanistan. The deal would conclude one of the most disastrous military engagements in U.S. history, while fulfilling one of President Donald Trump’s most significant 2016 campaign pledges to end pointless foreign wars. And the deal also counts as the latest feather in Doha’s cap—possible only, say Qatari officials and the country’s admirers, through a U.S. partnership with a country that sees itself as friend to all. And for critics of Qatar, that’s precisely the problem.

“Qatar is a profoundly menacing influence to core U.S. interests,” says a U.S. expert on Gulf affairs who asked for anonymity. “The issue is that they’re structurally promiscuous—they’re always trying to buy protection everywhere, that they give money to U.S. enemies—like the Muslim Brotherhood or Hezbollah or Hamas or the Nusra Front in Syria. The Qataris are supposed to be allies of the United States yet they’re funding and dealing with groups and countries that are inimical to American interests.”

To hear Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates tell it, it’s because of Qatar’s support for those groups and countries that it imposed a blockade on its fellow Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) state in June 2017. Riyadh and Abu Dhabi issued 13 demands that Doha was obliged to meet before the embargo would be lifted. Among other demands, the Saudis and Emiratis said Qatar had to shut down its world-famous satellite news station Al-Jazeera, stop supporting the Muslim Brotherhood and armed Islamist groups, pull away from Iran, and cease interference in the internal affairs of its neighbors, namely Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Another demand required Qatar to align its “military, political, social and economic policies with the other Gulf and Arab countries.”

From Doha’s perspective, the demands were tantamount to asking Qatar to forsake its sovereignty. But from Riyadh’s and Abu Dhabi’s point of view, their smaller neighbor’s policies represent a strategic threat, especially, say pro-Saudi and Emirati figures, Qatar’s relations with Islamists across the Muslim world, like the Taliban—as well as Hamas, Hezbollah, Iraqi-based Shia militias, and Sunni terror groups.

The conflict between the two GCC blocs has resulted in a massive influx of Gulf wealth into Washington as lobbyists, consultants, think-tank experts and journalists fill roster slots on the two competing sides. Former Florida Congresswoman Ileana Ros-Lehtinen is among the latest big Beltway names to register as a UAE lobbyist, while South Carolina Sen. Lindsey Graham’s former deputy chief of staff signed on with Qatar last summer.

There is nothing secret about the money that foreign powers spread around the U.S. capital, of course. Indeed, the purpose of spending money is to openly demonstrate power and influence. The point of taking money from foreign powers, aside from the money of course, is to align oneself with the power their money represents. None of the Americans I spoke to for this story was less than open, some boastful, about their working relationship with one or the other side of the GCC conflict.

As far as Donald Trump is concerned, the GCC Cold War is also good for America. The White House says publicly that it wants the two sides, all U.S. allies, to resolve their differences, but before Wall Street crashed their multi-billion-dollar fight fueled the U.S. work force. To compete for Trump’s favor, both sides of the GCC conflict spent lavishly, buying arms, military planes as well as civilian carriers, and investing in real estate and manufacturing throughout the country, from New York to Texas. The jobs created by Gulf spending was a significant part of why in April the United States enjoyed the lowest unemployment rate since 1969.

But are the massive waves of Gulf cash that are washing over Washington and the rest of the country actually good for America? The Gulf states, after all, abide by a very different set of values than Americans do, or did, in a secularized free-market Western democracy. And as rapidly as U.S. regional partners are modernizing under dynamic leadership like Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and Qatari Emir Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, there is still a long way to go. The workforce Qatar has imported from the Asian subcontinent to build 2022 World Cup sites is described, with only slight exaggeration, as slave labor.

At times, it seems like American foreign policy decision-making, especially when related to the Middle East and the Muslim world, has itself become a proxy battle between the two opposing camps in the Gulf. Saudi Arabia is critical of Qatar’s relationship with terrorist groups but skip over its own past relationship with Hamas. Both Riyadh and Abu Dhabi reportedly tried to act as mediators with the Taliban.

Insofar as the Afghan peace deal may answer America’s ardent desire to scale down its presence in the Middle East, it also poses something of a dilemma for Qatar, which has perhaps benefited more than anyone else from America’s post-Sept. 11 presence in the region. Recently, the Pentagon has been preparing for its departure from the Middle East, shifting some of its drone operations from Qatar’s massive and state-of-the-art Al Udeid airbase to South Carolina.

So what will Qatar do without the Americans in the desert? Transfer their holdings to America, of course. Qatar’s brutal struggle with its GCC rivals for supremacy in Washington is also an effort to shape the country’s future, and perhaps its survival.

The Qataris came to their wealth relatively late, in the early to mid-1990s. Where most of their Gulf neighbors rely on oil as their source of income, the Qataris found natural gas in the Gulf separating them from Iran. The two share the largest natural gas field in the world. Qatar’s natural gas infrastructure was built largely by Exxon, then under the leadership of Donald Trump’s future secretary of state, Rex Tillerson. Qatar has the highest per capita income in the world, with a total population slightly under 2.5 million, most of which are guest workers, including European lawyers and consultants at the top of the scale, and at the bottom South Asian laborers. The largest nationality is Indian, with 650,000, nearly twice the number of native Qataris.

Since the natural gas discoveries that put Qatar on the world map, there have been three key periods in the country’s history: 1995-2013, the reign of Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, which saw the rise of Qatar as a world player; 2013-2017, the foreign policy reset under the reign of his son Tamim; and 2017 to present, during which the intra-GCC conflict in Washington has driven Qatari strategy.

Qatar has been ruled by the Al Thani family since the mid-19th century. The leading historical figure in account of the country’s history is indisputably Sheikh Hamad, the former emir who governed from 1995-2013, and plotted the country’s ascendance through vast energy resources and international investment. By building both Al-Jazeera and the Al Udeid airbase, Hamad institutionalized the country’s foreign policy. Allies describe that policy as being friends with everyone—adversaries, in particular Saudi Arabia and the UAE, call it reckless and schizophrenic.

As the Arab Spring began in 2011, Sheikh Hamad staked Qatari interests to the rise of political Islam, supporting Islamist parties in Egypt and Tunisia as well as armed groups in Libya and Syria. His miscalculations earned Doha the ire of its more traditional neighbors in Riyadh and Abu Dhabi. In 2013, Qatar rebooted when Hamad stepped down in favor of his now 39-year-old son, Tamim, the darling of his mother Moza bint Nasser, the most glamorous and influential of Hamad’s four wives.

Within four years, Tamim would find himself in the middle of a crisis, the blockade, that many say is the result of his father’s support for Islamism.

“Iran is not the number one issue dividing the GCC states,” says Middle East expert Shadi Hamid. “Dubai has closer trade relations with Iran than Doha does.” Intra-GCC relations, explains Hamid, “really soured over the Arab Spring. Saudi Arabia and the UAE pressured Qatar over its support for the Islamists and that pressure culminated in the blockade.”

Other regional experts believe it was nearly inevitable that Qatar would back Islamist movements.

“As a small state next to big state, you’re swimming upstream,” says Middle East analyst David Des Roches. He likens Qatar’s relationship with Saudi Arabia to Canada and the U.S. “It seems strange, for instance, that the Canadians go out of their way to accommodate Cuba,” says Des Roches. “But that’s one way they distinguish themselves from the Americans. The contrariness is in part to avoid assimilation.”

Qatar’s complicated political strategy is shaped by its geography, its relations with a superpower patron, its natural resources, as well as the temperament of its ruling family.

Saudi Arabia is not the only large neighbor Qatar has to reckon with. Its wealth, security, and ability to project power are also shaped by its relations with Iran, which owns the South Pars field, and Qatar the bordering North Dome field. Further complicating matters is that Saudi Arabia, the leader of the Sunni Arab world, and Iran, led by a Shiite clerical regime, are engaged in a Cold War-style competition over the Muslim world. At times the conflict has erupted into actual military operations, as in the spring when Iran launched missiles at Saudi oil facilities. With both countries, Doha balances accommodation and aggression, though the latter is typically sublimated since it cannot afford to turn either into a dagger pointed at its heart.

For instance, consider how Qatar navigated the targeted killing of Iranian commander Qassem Soleimani. Critics of Qatar were quick to note that Sheikh Tamim was the first head of state to visit Iran after the strike. He and President Hassan Rouhani agreed that deescalation and dialogue were the only way forward. Rouhani must have been gritting his teeth, though—for the U.S. drones dispatched to kill Soleimani were launched from the U.S. base in Qatar.

Qatar plays a double game, as its critics claim, but as the episode illustrates, Doha also understands that Washington is its most important ally, its protective shield. That relationship was formally recognized in the wake of Operation Desert Storm when in 1992 Washington and Doha concluded a Defense Cooperation Agreement dealing with a U.S. troop presence in Qatar, the prepositioning of U.S. military equipment, and arms sales. The agreement was renewed in 2013 for another 10 years, a relatively short period in the context of a region that has seen mighty empires fade.

In 1995, Hamad overthrew his father, Khalifa bin Hamad Al Thani in a bloodless coup. At the time, the Saudis and Emiratis sided with the father and reportedly tried to restore him to the throne. As status quo powers, both dislike regional instability. As royal families, they frown on family coups, fearing the example may inspire similar attempts among their own kin. Further, says Lebanese political activist Lokman Slim, “Saudi sees itself as the father of the Gulf, and everyone has to kiss the ring and follow its lead. The Saudis see Qatar not just as a smaller local power but as a province of Saudi.” In fact, the royal families of both Saudi Arabia and Qatar are from the same region on the Arabian Peninsula, the Nejd. Thus the regional conflict is partly tribal, a conflict between a smaller clan and a larger one.

“Saudi Arabia believes it is its manifest destiny to lead the Gulf,” says Washington, D.C.-based Middle East analyst Sigurd Neubauer. “Same with the UAE. Saudi because of its size and the UAE because they believe they’ve figured it all out. They built cities people want to live in, like Dubai, which they see as the wave of the future. They want Qatar to fold in. Psychologically, a barrier was crossed when Qatar got the World Cup. The Saudis and Emiratis didn’t understand how Qatar could host the World Cup and they couldn’t.”

To influence opinion and project power in the region and abroad, Qatar uses both soft-power instruments, like media, sports, and culture, as well as hard power. Hamad’s two earliest and most significant projects illustrate the nature of Qatari statecraft—a hard- and soft-power initiative that showed Qatar was friendly to both sides, or playing a double game. In 1996, Doha spent $1 billion to build the Al Udeid air base, which would become a key node for U.S. military operations after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. The same year, Hamad unveiled a new venture that was destined to transform global media while it gave voice to anti-Americanism, most notably Osama bin Laden’s—Al-Jazeera.

After Sept. 11 and the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq, the satellite news network became one of the most famous press organizations in the world. Previously Arab media consisted of dozens of closed national markets, typically controlled by the state or political clans and intelligence services shaping the news according to the predilections of the ruling power. Al-Jazeera covered events across the region and, perhaps most important to Arab television audiences tired of coverage packaged to flatter their rulers, took on the ruling regimes, especially the regional powerhouses aligned with Washington, Egypt and Saudi Arabia—which, not incidentally, were also Qatari targets.

Although the network’s original staff came from the BBC’s failed experiment with an Arabic-language network, its ideological orientation was openly pro-Islamist. Its most famous broadcast personality was Yusuf al-Qaradawi, an Egyptian-born scholar of Sunni Islam who moved to Doha in 1961 to escape Gamal Abdel Nasser’s anti-Muslim Brotherhood purges. Qaradawi became Qatar’s academic and media impresario. His Al-Jazeera show, “Sharia and Life,” dispensed advice on everything ranging from masturbation to suicide bombing, both of which were permitted, but the latter only against Israelis.

Qaradawi was the cornerstone of Al-Jazeera’s post-Sept. 11 coverage, when the network won world renown for exclusively broadcasting bin Laden’s videotape messages. Al-Jazeera’s coverage of the 2003 U.S.-led invasion of Iraq was proudly pro-resistance. In 2004, Qaradawi issued a fatwa contending it was the duty of Muslims to resist the “occupying forces.”

At the same time, the United States was running missions out of Al Udeid against the very same forces Al-Jazeera was cheering. The policy, say critics, is not evenhanded but schizophrenic.

“In 2003 the U.S. had moved out of Saudi Arabia because Islamist ideologues had denounced the U.S. presence in the Arabian peninsula,” says a Saudi analyst. “The U.S. moved to Al Udeid and now the Qataris are paying the same Saudi Islamists who wanted the U.S. gone. They’re visiting the emir, only a very short drive to Al Udeid.”

Al Udeid airbase and Al-Jazeera became the foundations on which Qatar built its global influence campaign. Next came a hand-picked selection of major U.S. universities, apparently chosen both for their own areas of excellence and physical locations in the U.S., that opened campuses in Doha. According to a 2016 report, Qatar spends more than $400 million per year sustaining the Doha campuses of six U.S. universities—Carnegie-Mellon, Georgetown, Northwestern, Texas A&M, Weill Cornell Medical College, an outpost of Cornell University’s medical school, and Virginia Commonwealth University’s arts campus.

Qatar may spend even more money directly on higher education institutions in the U.S. American media reported last month that Qatar is one among several countries, including Saudi Arabia and China, that flooded top universities like Yale and Harvard with more than $6.5 billion in unreported foreign funding. A study by the Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy found that “Federal reporting requirements and procedures have been inadequate at keeping track of funding coming in from abroad. This includes more than 3 billion dollars gifted by Qatar and the Gulf States, which were never reported by universities to the IRS or Department of Education.”

Qatar’s influence-buying strategies are a textbook example of how to transform cash into soft power.

Qatar has also funded high schools, through Arabic-language programs.Since 2009, Qatar Foundation International “has provided direct support to schools that want to establish or expand Arabic-language programs at the primary and secondary school level. By 2017, according to a Wall Street Journal report, over the eight-year period QFI gave $30.6 million “to several dozen schools from New York to Oregon and supporting initiatives to create or encourage the growth of Arabic programs.”

Doha’s global engagement with and through art is overseen by Moza bint Nasser, one of Qatar’s key decision-makers, and as a patron of the arts an unofficial envoy to the West who helps to promote Qatar’s openness to the rest of the world.

“Qatar has been quite methodical in setting up museums,” says a former U.S. official who served for several years in Doha and became close to the ruling family. “She has an interest in global and regional art. She sees culture and education as key cornerstones.”

Qatari museums include the Museum of Islamic Art, National Museum of Qatar, Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, ALRIWAQ, and Katara. Qatar is believed to spend over $1 billion annually on art–a number that may vastly understate such expenditures. Qatar’s investment in art, writes one critic, is “about showcasing and continuing Arab Identity. The challenge for Qatar, and the reason they’ve developed so differently from the UAE, is how to become a modern country without adopting Western Culture.”

Unfortunately, one of the central planks of modern Arab identity over the last 70-plus years in addition to patronage of the arts has been anti-Zionism. Thus, Moza also helped to incubate the Boycott, Divestment. and Sanctions movement on American college campuses. A 2009 Department of Justice document shows that she employed Fenton, the U.S.-based communications firm where J Street founder Jeremy Ben Ami had worked in a top-level position until leaving to form the progressive AIPAC rival at the end of 2007, though there is no evidence to tie Ben Ami to the Qatari campaign. Fenton’s job was to help set up Fakhoora, a Doha-based organization that targeted students in the United States. A declaration posted on Fakhoora’s website, states the group’s aim to: “isolate Israeli apartheid through events tied to Palestinian civil society’s call for Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions.” A document from February 2010 titled “Fenton Communications Contract for the Al Fakhoora Campaign” has been preserved by the Justice Department in its digital archive of FARA filings. Among the activities that Fenton agrees to provide its client “Her Highness Sheikha Mozah Bint Nasser Al-Missned, it includes the following: “Managing and building ongoing relationships with U.S. students and working with partner organizations to manage other student relationships in Europe and the Middle East.” In addition to promoting BDS and other anti-Israel measures on campuses, Fakhoora was also involved in less academic forms of activism. The organization’s director, Farooq Burney, was on board the Turkish-owned ship the Mavi Marmara that attempted to run the Gaza blockade in 2010.

The same report that totaled over $3 billion in Qatari funding of higher education in the U.S. also noted “a direct correlation between the funding of universities by Qatar and the Gulf States with the presence of groups such as Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP) and a deteriorating environment that fosters an anti-Semitic and aggressive atmosphere.” With the bulk of all Middle Eastern donations emanating from Qatari donors (75%), and the Qatar Foundation accounting for virtually all of the donations from Qatar, the report concluded, “these funds significantly impact attitudes, anti-Semitic culture and BDS activities.”

In midwinter I’m having lunch with a former European official with extensive experience in the Middle East who offered to explain Qatar’s investment strategy. To make the point, he suggested we meet at the Conrad, the newly opened 360-room hotel in downtown Washington that is the crown jewel of Doha’s Beltway holdings—CityCenterDC. The multiuse (residential, retail, office) real estate project blocks from the White House that broke ground in 2011 with a $620 million investment from Qatari Diar Real Estate Company, the real estate investment arm of the Qatar Investment Authority. The 10-acre lot hosts retail brands like Ferragamo, Hermès, Paul Stuart, and international restaurant groups like DBGB, and Momofuku. The Conrad’s main dining room is Estuary, a minimalist hall in grays and browns.

Qatar’s investment strategy, says the official, “is partly based on watching what their neighbors the Saudis and Emiratis did with their wealth.”

There were both successes and failures. “The Emiratis created cities out of nothing” he says, “like Dubai and Abu Dhabi, that are the envy of much of the rest of the world.”

New Yorkers, Parisians, even Cairenes and Beirutis can afford to think of the giant structures as steel and glass monstrosities planted in an arid desert. But to Asia and Africa and the former Soviet states, Dubai and Doha aren’t just travel hubs connecting, say, Mumbai to London, but represent some of the few opportunities available to a Filipino father or single mother from Kazakhstan to pull themselves out of poverty.

“Qatar had a big advantage,” the official explains. “They came to their wealth after their neighbors. The Qataris know their gas will run out at some point. Their investments are looking to the future, to make sure they’re OK when their resources are exhausted.”

To expand Doha’s portfolio, and minimize its reliance on energy prices, in 2005 Hamad founded the Qatar Investment Authority which now has nearly $330 billion in assets. The QIA has extensive investments throughout Europe, with significant stakes in brand name British, French, and German corporations and financial institutions, including Volkswagen, Porsche, France Telecom, Credit Suisse, and Royal Dutch Shell. It’s holdings in London alone include Sainsbury’s, Harrods, the Olympic village, the U.S. Embassy building in Grosvenor Square, as well as 8% of the London Stock Exchange, a similar cut of Barclays and a quarter of Sainsbury’s. In total, they own more of London, it is said, than the Crown Estate.

ANDREAS SOLARO/AFP via Getty Images

Among the best known European brands the Qataris have invested in are football teams, which also allows them to compete with the similarly soccer-crazy Emiratis. Both see it as a way to promote their global brand. In 2012 Qatar Sports Investments bought the French soccer team, Paris Saint-Germain. Qatar Airways, the state-owned national carrier, sponsors a number of major teams around the world, including the Italian club AS Roma, the German league’s Bayern Munich, Boca Juniors in Argentina, and formerly the perennial Spanish powerhouse Barcelona FC.

Most prominently, Qatar is host to the 2022 World Cup. Construction of the various sites, like new stadiums and hotels, depends on cheap labor from Bangladesh and elsewhere from the Asian subcontinent. A 2015 report showed that 1,200 workers had died and estimates suggest that by the time of the first kickoff in November 2022 there may be a total of 4,000 dead.

Critics of Qatar describe Doha’s efforts to launder its human rights abuses through well-known sports brands “sportwashing.” The criticism is apt, but fortunes are typically used to obscure the less than pleasant means through which they were acquired. What was good enough for the Medicis and the Carnegies is good enough for the Al Thani.

Qatar, says National Defense University professor David Des Roches, “has a very conscious strategy to gain influence. They’re open about the purpose of hosting meetings, international conferences and exhibitions.”

According to a WikiLeaks cable from 2009, one Doha-based expatriate told a U.S. diplomat that “Qataris had explained to him that their drive for international conferences, their hosting of U.S. military bases, and their relentless engagement with others were all part of a strategy to protect Qatar. ‘We have no military,” one Qatari told him, “so think of the conferences as our aircraft carriers, and the military bases as our nuclear weapons.’”

The expat was Hady Amr, a Beirut-born U.S. citizen who served in the Obama administration, after his term as director of Brookings Doha Center.

The relationship between one of Washington, D.C.’s top think tanks and Qatar began in 2002, when the emirate underwrote a Doha conference featuring Qatari Foreign Minister Hamad bin Jassem Al Thani (HBJ) and former U.S. Ambassador to Israel Martin Indyk, then the director of the Saban Center for Middle East Policy at Brookings. In 2007, Brookings announced it was opening a center in Doha.

“The Brookings Doha Center will seek to forge a lasting partnership between the leading policymakers and scholars of the United States, and those of the Muslim world,” Indyk said in the press release. “It will also host visiting fellows both from Brookings and the Muslim world.”

Some saw the combination of a state power and a research institution as questionable.

“If a member of Congress is using the Brookings reports, they should be aware—they are not getting the full story,” said Saleem Ali, who served as a visiting fellow at the Brookings Doha Center in Qatar and who said he had been told during his job interview that he could not take positions critical of the Qatari government in papers. “They may not be getting a false story, but they are not getting the full story.”

Between 2002 and 2010, Brookings did not disclose how much it received from Qatar. In 2011, Qatar gave Brookings $2.9 million, $100,000 in 2012, and in 2013 a four-year grant of $14.8 million in 2013, just as Indyk became the Obama administration’s envoy to the Israeli-Palestinian peace process. In both 2018 and 2019, the embassy of Qatar donated to Brookings at least $2 million.

Much of Doha’s engagement with the world is run out of the Qatar Meeting, Incentive, Conference and Exhibition (MICE) Development Institute (QMDI), which promotes Qatar as a good place for business. The annual Doha Forum gathers major policymakers from around the world—Trump’s daughter Ivanka, Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin, and Sen. Lindsey Graham were among the biggest names at the 2019 edition. Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif was also in attendance. In 2018, Qatar paid for the trips of six Democratic congressmen attending the forum.

The Doha Forum also teams up with a number of strategic partners, including U.S. media outlets, like Bloomberg, Foreign Policy magazine, and BuzzFeed, whose reporters’ travel and lodgings to cover the forum in 2019 were covered by the forum. A number of U.S.-based think tanks signed on as strategic partners for the 2019 edition, including the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the McCain Institute, the Rand Corporation, the Wilson Center, the Stimson Center, and the International Crisis Group. A March 2019 report in the Washington Free Beacon showed that Qatar gave the ICG $4 million. Its president, Robert Malley, a former Obama administration aide, is often quoted as an impartial Middle East NGO expert in the New York Times.

Some regional analysts argue that that Qatar’s role as intermediary can be helpful to others, including helping to free hostages. In November, Trump thanked Sheikh Tamim for Qatar’s help in freeing a U.S. hostage, and another from Australia, from the Taliban. Qatar also played a role in securing U.S. soldier Bowe Berghdal’s 2014 release in exchange for five high-profile Taliban figures held by U.S. forces in Afghanistan.

According to a study by Jonathan Schanzer, vice president at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, between 2011 and 2017, Qatar was a participant in hostage talks 18 times. Doha paid hundreds of millions of dollars to terror groups in Yemen, Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq for the release of Arab, Western, and Asian hostages. Qatar’s critics, led by Saudi Arabia, claimed that Doha was using kidnappings as a screen to fund terror groups. In truth, the distinction between paying large sums in ransom to terror groups and simply writing them large checks may not be a functionally meaningful–to terror groups, at least.

The GCC blockade on Qatar was imposed in part, say several sources, because of a massive ransom payment to both Sunni and Shiite terror groups that won the release of dozens of Qataris, including members of the royal family, kidnapped in Iraq during a hunting expedition. Negotiations to free them lasted more than a year and a half, ending in April 2017 when the Qataris paid hundreds of millions of dollars to Sunni terror groups as well as Iranian-affiliated militias and the IRGC itself. Qassem Soleimani alone is believed to have cleared $50 million with the deal.

Qatar’s complicated political strategy is shaped by its geography, its relations with a superpower patron, its natural resources, as well as the temperament of its ruling family.

The Saudis were furious. “It’s understandable they want to free their people,” says a Saudi analyst with ties to the royal palace. “But that money is used to fight Saudi Arabia. Every day Riyadh has to fight al-Qaida. The Iranians are firing missiles on our airports. Qatar doesn’t have those worries.”

Doha says that it’s fighting terrorism. Qatari officials I spoke with pointed proudly to the U.S.-Qatar memorandum of understanding on terror financing signed a month after the June 2017 embargo. “The agreement which we both have signed on behalf of our governments represents weeks of intensive discussions between experts and reinvigorates the spirit of the Riyadh summit,” Secretary of State Tillerson said at a joint news conference with Qatari Foreign Minister Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al Thani.

“They’re making good progress,” says a former U.S. official. “More work needs to be done, but you can say that about every country in the Gulf.”

Others are more skeptical. “The U.S. has wanted that terror financing MOU for a while and they only got it after the blockade because the Qataris were up against the wall,” says a Saudi analyst.

The Qataris have historically been lax about prosecuting and convicting terror financiers. At times, they’ve protected them. In the 1990s, Qatar sheltered top al-Qaida leader Khalid Sheikh Mohammed. As the FBI closed in on him in 1996, Abdullah Bin Khalid al-Thani, a member of the royal family and a former interior minister tipped off the bin Laden deputy.

“The fact that Qatar signed the MOU that the U.S. has been trying to get them to sign for 10 years proves the point we’ve been making,” says the Saudi analyst. “You can’t have 10,000 U.S. troops and U.S.-designated terrorists running loose in the same Doha malls. You can’t have them running into U.S. troops at Krispy Kreme—it is a very sensible ask by the Americans.”

Oddly, the government of Israel appears to support at least some of Qatar’s terror financing. Even as Jerusalem has complained that Doha hosts Hamas officials like Ismail Haniyeh, Israel has also allowed Qatar to continue pouring money into Gaza in the hopes of preventing another war. According to Avigdor Lieberman, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu sent senior intelligence and military officials to Doha to “beg” the Qataris to continue paying Hamas, even though Doha is fed up with the Palestinian terror organization.

The Saudis have their own checkered history with terror financing, often ignoring the role that Saudis on the margins of the ruling establishment played in funding and inciting attacks. It was only when al-Qaida waged major operations inside the kingdom, targeting expatriates and security forces, shortly after Sept. 11 that Riyadh recognized it had to crack down on terror. Qatar has not had to face that dilemma, and perhaps never will.

“Qatari foreign policy is like an insurance policy,” says one U.S.-based historian of the region. “Their main regional activity is to use the Muslim Brotherhood to project influence. It’s like the former Soviet Union, which used local communist parties around the world to spread their influence. The Qataris do the same with the Brotherhood, whether it’s in Tunisia, or Egypt or France. It’s not that it’s a more sophisticated model than the Saudis. Riyadh doesn’t have grassroots movements to draw on. Qatar does.”

Further, explains Middle East expert Shadi Hamid, “Saudi Arabia and the UAE see the Muslim Brotherhood as an existential challenge. They see it as secretive, and dealing in double discourse. For them it’s a threat. They feel anti-MB very strongly. They have their own Islamist vision. They promote the idea of a statist, quietist Islam.”

As Middle East expert Thomas Pierret wrote: “Saudi Arabia does not only despise the Muslim Brothers, but political Islamic movements and mass politics in general, which it sees as a threat to its model of absolute patrimonial monarchy. Saudi policies are not driven by religious doctrines, as is too often assumed, but by concerns for the stability of the kingdom, which translate into support for political forces that are inherently conservative or hostile to Islamist movements.”

Saudi and other critics charge that Qatari foreign policy is designed to appease terror groups. But Qatari leadership doesn’t see the Muslim Brotherhood as a threat, says Hamid. Author of Islamic Exceptionalism: How the Struggle Over Islam Is Reshaping the World, Hamid writes frequently on the Brotherhood and lived in Qatar for four years, working at Brookings Doha. “There was a Qatari Muslim Brotherhood organization, but it dissolved itself in 1999,” Hamid says. “It’s a small country and so it’s hard to recruit members there. In addition, given the country’s wealth, there are relatively few disaffected citizens, few of the kinds of people who are typically attracted to the Brotherhood’s promises of social justice and the services it normally provides around the Muslim countries.”

Hamid and other regional experts say that the blockade is fundamentally about political Islam. Doha backed Brotherhood groups around the region, most prominently in Egypt and Syria. “That Qatar supports some Islamist movements the Saudis and Emiratis see as interference in their domestic affairs,” says Hamid. “That’s why they take it personally. Any MB branch they consider problematic. The issue is that the Qataris don’t have any incentive to give up support for these groups, and lose influence. With the blockade, the Saudis and Emiratis wanted to send the message that the Arab world can’t go through the chaos of something like the Arab Spring again.”

After the Arab Spring’s spectacular failure, Doha sought to reset relations with its neighbors and transferred power within the Al Thani family and Tamim replaced Hamad.

“The official line was that the transition from father to son was always planned,” says Neubauer. “But it can be argued that the 2013 abdication in Qatar was triggered by its Arab spring policies, especially in Egypt and Syria, and Doha wanted to start with a clean state. From Qatar’s perspective, post 2013, it did everything the Saudis had asked it to do.”

Other experts say that Tamim is simply a figurehead and Hamad is still calling the shots, along with the powerful former Prime Minister Hamad Bin Jassem, known as HBJ. “HBJ is very pro-Brotherhood and pro-Arab nationalist,” says one regional analyst. “Also, in private settings he’s made it clear he doesn’t like America very much.”

In November 2013, the GCC leaders, including the newly crowned Tamim, met in the Saudi capital to sign the “Riyadh agreement,” pledging not to interfere in the internal politics of their neighbors. They were to stop supporting opposition groups and “antagonistic” media, meaning, it seems, Al-Jazeera. But in an action that foreshadowed the June 2017 embargo, in March 2014, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Bahrain withdrew their ambassadors from Doha claiming that Qatar had not lived up to its part of the bargain.

After the Saudis and Emiratis asked the Qataris to shut down its pro-Muslim Brotherhood network, Doha diversified its portfolio with investments in secular programming—that is, an Arab nationalist network. In January 2015, Qatar launched Al Araby, a London-based Arabic-language network positioned as a counterweight to Al-Jazeera. The power behind the station is Azmi Bishara, the 63-year-old former Marxist who founded the Israeli Arab political party, Balad. In 2007, Bishara fled Israel under suspicion of spying for Hezbollah and the Assad regime during the second Lebanon war.

He landed in Doha where, like Qaradawi decades before, he became a consigliere to the ruling family.

“When Tamim wants to see him, the palace has to check to make sure Bishara’s schedule is clear,” a prominent Saudi journalist told me, half in jest.

Bishara told the French media he doesn’t have an official role under the emir. “I’m an intellectual and there is friendship and trust between us. When he wants my opinion, I give it to him. I am less than a counselor and more than a counselor.”

Bishara is head of the Arab Center for Research and Policy Center, a Doha-based think-tank with a branch in Washington, D.C. Fellows there include Yousef Munayer, who defends the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement.

Others, however, say Bishara’s role is greatly overexaggerated. “He’s an old-school Arab nationalist,” a D.C.-based pro-Qatari activist told me on the phone. “The ruling family believes it has an obligation to protect these Palestinian intellectuals who have no one else to look out for them. Bishara isn’t running anything.”

Arab sources insist, however, that Bishara is Qatar’s new intellectual impresario. “He’s anti-Islamist because he’s an old-school Arab nationalist,” says a Saudi analyst. “These guys have always hated Saudi because they’re resentful of the oil wealth. ‘We taught the Bedouins math and they owe it to us to share their wealth!’ His interests are aligned with Qatar’s, for now, so he’s useful to them.”

Bishara, says independent Lebanese activist Lokman Slim, “knows how to work through the media, and he’s essentially running the secular wing of Qatari press.”

In addition to Al Araby, other recent secular media initiatives include the Arabic-language websites Al Araby Al Jadid (The New Arab), and Al-Modon (The Cities). The latter, says Slim, “probably has the best coverage of any Arab publication today.”

But it’s the London-based satellite network that has broken new ground. Al Araby’s most popular offering right now is “The Joe Show,” hosted by Egyptian comic Yussuf Hussein

“It’s very sharp and ironic,” says a colleague of Slim’s, a Lebanese businessman who asked I not use his name in print. “Frankly, it’s not really Arab humor, it’s more like Jewish humor.”

Slim laughs. “That’s the point about Bishara,” says the Lebanese activist. “It’s at a very high level because of where he’s from. It’s at an Israeli level.”

Recent Qatari media initiatives have weaponized Bishara’s anti-Israel sentiments as part of an influence campaign against American Jews—and a pro-Israel senior U.S. official. The 2018 Texas election Senate contest between Sen. Ted Cruz and Rep. Beto O’Rourke was the most heated and expensive campaign in Senate history. By the end of summer it was clear that Cruz, a noted critic of Qatar and Al-Jazeera, was vulnerable. At that point, Al-Jazeera and Al-Jazeera-linked outlets started pushing a political-style smear campaign targeting Omri Ceren, Cruz’s national security adviser. In late August of that year, viral videos began leaking from deep inside Al-Jazeera about a film project created by a pro-Palestinian filmmaker who had secretly run a monthslong sting operation in Washington, D.C., surreptitiously recording conversations with American Jews.

The filmmaker, pretending to be a British pro-Israel advocate, had specifically infiltrated the Israel Project, a pro-Israel nonprofit where Ceren was then the managing director. The resulting documentary had been bottled up for years by the Qatari government to prevent diplomatic blowback from what seemed like an espionage operation against American Jews run on American soil. Now suddenly it was being let out little by little, against the backdrop of stories questioning the loyalty of those Jews from outlets like The Intercept. By the end of October, the full documentary had leaked.

In 2019, with $30 billion already invested in the United States, the QIA announced last year it was planning to raise that to $45 billion, focusing primarily on technology and real estate. QIA had already made inroads in the tech sector when in December 2017 it took software company Gigamon private for $1.6 billion in concert with Elliott Management.

As for real estate, Qatar continues to build on its extensive U.S. holdings. CityCenterDC is only the largest and best known of its Washington, D.C., projects. In April 2017, a delegation of D.C. officials and private investors visited Doha to encourage further real estate projects, including hotels. Several Qatari firms already own D.C. hotels. Al Rayyan Tourism Investment Co. bought the St. Regis in 2015; Al Sraiya Holding Group bought the Club Quarters for $52.4 million in 2016; and Alduwaliya purchased the Homewood Suites near the Washington Convention Center for $50.4 million in early 2017.

Alduwaliya, a multi-billion-dollar global private equity fund on behalf of the Qatari royal family investing in commercial real estate, has made numerous purchases in the capital, including a 12-story office building on Connecticut Avenue NW for $64 million, and another on Thomas Jefferson Street for $142 million.

The same firm has been active in several other cities, too. In 2019, Alduwaliya bought two office properties in Boston’s financial district for $107.8 million. In New York, Alduwaliya has bought several buildings in the garment district: in 2015, it purchased an office building on 39th Street for $123.5 million; in 2016, the Hilton Homewood Suites on W. 37th Street for $167.1 million; and in 2019, it spent $140 million for two more buildings in the area.

A 2018 deal to bailout a New York skyscraper compelled QIA to consolidate its investment strategy. Qatar had invested in Brookfield, which struck a deal to rescue 666 Fifth Avenue, owned by the family of Jared Kushner. The president’s adviser, and son-in-law, is famously friendly with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. Qatari leadership, which reportedly only learned of the $1.8 billion deal, at the time a record for a New York office building, was concerned the purchase appeared like an attempt to influence the administration. Although the QIA was not directly involved in the deal, the Qatari fund resolved to stop putting money in funds it does not fully control.

The reality of course is that Qatari spending is intended to influence U.S. politics. If there was a concern over the 666 Fifth Avenue deal, it was simply that it appeared to be too direct of an influence play.

Qatar invested in other industries besides real estate, like energy infrastructure. Last year it struck a $10 billion deal with ExxonMobil to expand a liquified natural gas terminal in Texas, home to Sen. Ted Cruz.

Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin greets the emir of Qatar, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani at the Treasury Department for a dinner with President Donald Trump in Washington, D.C., on July 8, 2019NICHOLAS KAMM/AFP via Getty Images

In spring 2018, Qatar convened a business forum in Miami. Qatar saw an opportunity with Miami’s new Major League Soccer franchise, owned by retired British star David Beckham. The Qatar Foundation signed a $180 million sponsorship deal with Inter Miami.

In September 2017, three months after the blockade was imposed, Trump met with Tamim at the U.N. General Assembly, and a Qatari lobbyist told Reuters that Doha pledged to spend more money on Al Udeid and buy aircraft from Boeing Co. Less than a week later,

Qatar Airways announced a $2.16 billion purchase of six Boeing aircraft. Doha was building on its already existing relationship with the manufacturer. In 2016 Qatar Airways struck an $11 billion deal with Boeing that included 30 787 Dreamliners, which are built in Charleston, South Carolina.

In February 2018, senior officials from the Qatar Investment Authority made their first official trip to the city. “I hope our presence here will develop further,” Abdullah bin Mohammed Al Thani, QIA’s CEO told business leaders during a visit to Charleston, where he met with the senior senator from South Carolina, Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham, and Gov. Henry McMaster.

The top donor to McMaster’s gubernatorial campaign, reported Jordan Schachtel, was a Qatari lobbyist, Imaad Zuberi, who represents the QIA, and, with his family and affiliated companies, gave the campaign more than $50,000. Zuberi was a major fundraiser for Obama and Clinton, and supported the Clinton Foundation, but also donated almost $1 million to Trump’s inaugural committee.

A month after the QIA’s maiden trip to Charleston, Qatar established Barzan Aeronautical, a subsidiary of Barzan Holdings, the strategic investment arm of Qatar’s armed forces, “to build out a large military aircraft initiative that is expected to support numerous jobs.”

Traditional U.S. Middle East allies like Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates greeted the election of Donald Trump with relief, expecting a return to conventional American regional strategy of which they were the cornerstones. Where the Obama White House had swapped them out in exchange for the Islamic Republic of Iran, Trump had denounced the Iran nuclear deal on the campaign trail and promised to restore relations with the Saudis. Trump made his first foreign visit to Riyadh, on May 20, 2017. The trip was a success, as the Saudis gathered leaders from around the Muslim and Arab world to hear the American president promise friendship while counseling them to deal with their terrorism problem.

Behind the scenes, however, the intra-GCC conflict was heating up. On May 23, the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies (FDD) and the Hudson Institute (where I’m a senior fellow), held a conference on Qatar and the Muslim Brotherhood with high-profile former U.S. officials, like one-time Pentagon chief Robert Gates, and Republican Congressman Ed Royce. Then chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, Royce announced he was sponsoring legislation to sanction Qatar for supporting Hamas.

The conference was funded by Elliott Broidy, a Trump donor, deputy finance chair of the Republican National Committee, and a businessman who won contracts in the UAE for his private security firm. According to emails leaked to the AP, Broidy claimed he had “shifted” Royce from being critical of Saudi Arabia to “being critical of Qatar.” Broidy’s lawyers blamed Qatar for hacking their client’s emails, writing to the Qatari Embassy in the United States that they possessed “irrefutable evidence tying Qatar to this unlawful attack on, and espionage directed against, a prominent United States citizen within the territory of the United States.”

On May 24, Qatar’s own news agency website was hacked, with statements attributed to Sheikh Tamim calling Hamas “the legitimate representative of the Palestinian people,” warning about confrontation with Iran, and claiming its relations with Israel were good. Doha immediately denied that the comments had been made by the emir, but they were nonetheless representative of Qatar’s friends-with-everyone foreign policy. Later reports claimed that Abu Dhabi was behind the hack, which Emirati Ambassador to the United States Yousef Al Otaiba denied.

The tit-for-tat hacking game between the two rivals would only escalate from there. On June 3, the Intercept published Otaiba’s hacked email correspondence with FDD CEO Mark Dubowitz and FDD Senior Counselor John Hannah. The hacked emails, according to the Intercept story, include an agenda for an upcoming meeting FDD and UAE government officials that was to discuss, among other items, “Al Jazeera as an instrument of regional instability.”

Two days later, on June 5, the Saudis and Emiratis imposed the blockade. They gambled that the president would take their side in the crisis. He’d embraced the Saudis. He’d done a sword dance in Riyadh during his maiden trip abroad. The new president had explained that Saudi investment in the United States, including billion-dollar arms purchases, put Americans to work. He saw the king and crown prince as stalwart allies in the conflict with Iran and the neverending war on Islamic extremism.

“Saudi Arabia and the UAE saw Trump as an opportunity to settle the Qatar question once and for all,” says Neubauer. “They equated Qatar with radical Islam, and then when they implemented the blockade Trump initially jumped on their side.”

On June 6, Trump tweeted:

Then-Secretary of State Tillerson counseled a more balanced approach. As former CEO and chairman of ExxonMobil, Tillerson knew all the players involved. The president’s stance was soon tempered. On June 7, he spoke with Tamim and offered to mediate the conflict.

“The President emphasized the importance of all countries in the region working together to prevent the financing of terrorist organizations and stop the promotion of extremist ideology,” the White House said in a statement.

Trump was reminded that U.S. relations with all the GCC states is good for U.S. business. Less than a week later, Doha purchased $12 billion worth of F-15s. In July, Washington and Doha signed the MOU on combating terror financing. Months later, Trump would eventually thank Qatar’s ruler, Sheik Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani for helping combat terrorism. The White House readout explained that Trump “reiterated his support for a strong, united Gulf Cooperation Council that is focused on countering regional threats.”

The White House was keen to see the conflict between its GCC partners resolved. According to Tamim, Trump told him, “I will not accept my friends fighting amongst themselves.” A fragmented GCC would make it more difficult to implement the Middle East policies most important to Trump—confront Iran, withdraw forces from Afghanistan and Iraq, and restore the special alliance with Israel. The Pentagon had also weighed in, reminding the White House that Qatar hosted important military bases that would be costly to replace.

The blockade brought Qatar’s strategic interests into even sharper focus. Qatar’s diplomatic engagement in D.C. was minimal, and incapable of matching up with UAE Ambassador Yousef Al Otaiba, known as one of D.C.’s most skillful and aggressive envoys, who was telling U.S. officials and allies that the administration should move the U.S. airbase out of Qatar. Soon, the Qataris started sending high-level delegations to meet with Washington foreign policy correspondents and think tank experts.

Doha had spent $4.2 million on lobbying in D.C. in the year before the blockade. By way of comparison, the Saudis had spent $77 million the previous decade. In 2017, Qatar bumped spending on lobbying up to $16.3 million, a huge surge, especially since the blockade was imposed halfway through the year.

By the end of 2017, Qatar had plotted a unique course, wooing figures close to the Trump administration, like former Trump campaign adviser Barry Bennett, whose lobbying firm won a $6 million contract with Doha. Former NYC Mayor Rudolph Giuliani worked on an investigation for the Qataris and visited Doha shortly before he was hired as the president’s lawyer in April 2018.

Qatar also hired the deputy chief of staff for Ted Cruz’s presidential campaign, Nick Muzin, to reach out to the American Jewish community. He and New York restaurateur Joey Allaham persuaded prominent Jewish figures like lawyer Alan Dershowitz, Zionist Organization of America head Morton Klein, and executive vice chairman of the Conference of Presidents of Major Jewish Organizations, Malcolm Hoenlein, to visit Doha and speak with Qatari officials. “Qatar tried something different,” former Trump adviser Steve Bannon told the Wall Street Journal. “Getting all of these influencers, the Jewish leaders and people close to the president, shows a high level of sophistication.”

Qatar’s real breakthrough, however, wouldn’t come until fall 2018, when it capitalized on the tragic blunder of its Saudi rival.

On Oct. 2, Saudi national Jamal Khashoggi was killed in the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul. His murder at the hands of Saudi intelligence officers was used as a platform for multiple information operations run by various actors, with multiple purposes. Turkish intelligence wanted to hang the murder on the crown prince of Saudi Arabia, a rival for regional primacy. There they had an ally in Qatar, whose operatives in Istanbul and Washington helped push the story to the U.S. press, which saw it as another opportunity to target Trump, and revive the Iran Deal.

From Doha, Azmi Bishara tied the murder to Trump. “What should occupy us is not the responsibility of Mohammed bin Salman for the barbaric act, because this is a given,and the waters of the whole of the Arabian Sea shall not wash his hands clean of Khashoggi’s blood, nor any deal or narrative proposed to him by Trump and his henchmen. No, what we should ask is this: What kind of leader makes such a criminal yet foolish decision?”

By putting the U.S. president’s face on MBS, Bishara and the others were sure to galvanize the anti-Trump resistance. Fittingly, Khashoggi’s murder became the platform for an information operation. In life, he had occupied the well-known gray area in Arab politics where media intersects with intelligence operations. It was Khashoggi’s relationship with Osama bin Laden—a friend whose death he mourned—that earned him the attention of longtime Saudi intelligence chief Turki al-Faisal, who appears to have used him as a back channel to al-Qaida. Faisal named Khashoggi his “media adviser” when he was ambassador to London, then Washington, and in Riyadh, hired him twice to run the newspaper he owned, Al Watan. To get around those inconvenient details of Khashoggi’s background and further his agenda, Bishara worked to rebrand Khashoggi as a “Washington Post journalist” and “permanent U.S. resident.” Accordingly, Trump was obliged to take action against Riyadh. “There is no way we’re gonna continue to do business with Saudi Arabia as if this never happened,” said Lindsey Graham, echoing anti-Riyadh talking points.

In reality, of course, Khashoggi was a foreign national with an apartment in northern Virginia who could barely write English—much of his work in the Washington Post was heavily shaped and at times effectively ghostwritten for him by a former U.S. foreign service officer, Maggie Mitchell Salem, as the Washington Post itself has reported.Salem was employed by Qatar Foundation International in Washington, D.C.

Lindsey Graham, whose home state was the recipient of some of Qatar’s largest direct investments, responsible for creating thousands of jobs in the state, was relentless in his attacks on MBS. “There’s no doubt in my mind that the killing of Mister Khashoggi was orchestrated by, approved by, and with knowledge of, the Crown Prince,” said Graham. “There’s no amount of oil coming out of Saudi Arabia and there’s no threat from Iran that will get me to back off,” he added. After a CIA briefing on the murder, Graham said, “I think he’s complicit in the murder of Mr. Khashoggi to the highest level possible.”

The Washington Post, whose owner, Jeff Bezos, blamed the Saudi crown prince for hacking his personal phone and releasing compromising communications with his mistress (federal prosecutors reportedly have evidence that the photographs were released by Bezos’ mistress’ brother), told prominent GOP lobbyist Ed Rogers of the BGR political lobbying group to stop representing Saudi Arabia or else he’d no longer be able to write for the Post, Congress’ hometown paper.

Six lobbying firms severed their relationships with Riyadh.

Yet the president stood by MBS, for the same reason he quickly made up with the Qataris—it’s good for American business. As Trump explained in a November 2018 statement after a trip to Saudi Arabia, “the Kingdom agreed to spend and invest $450 billion in the United States. … It will create hundreds of thousands of jobs, tremendous economic development, and much additional wealth for the United States. Of the $450 billion, $110 billion will be spent on the purchase of military equipment from Boeing, Lockheed Martin, Raytheon and many other great U.S. defense contractors. If we foolishly cancel these contracts, Russia and China would be the enormous beneficiaries—and very happy to acquire all of this newfound business. It would be a wonderful gift to them directly from the United States!”

It appears that as long as the GCC conflict continues, the Beltway will continue to profit—as will other American cities, from New York to Charleston, and U.S. industries, from defense to education. “Both sides believe Trump can impose a solution favorable to you and bad for your rivals,” says a D.C.-based Saudi lobbyist. “The U.S. put an embargo on Cuba that lasted more than half a century,” says a prominent Saudi journalist. “We can certainly do the same. And if anyone can afford it, Qatar can.”

Indeed, the Gulf states are accustomed to a certain level of internal conflict and managing contentious and, in a sense, tribal dynamics. However, it’s not contained to the Gulf. The extraordinary wealth of the actors involved has afforded them the opportunity to export the conflict abroad. The issue then isn’t really Qatar or any of the GCC countries, none of which is forcing anyone to take their money. Rather, the conflict underscores the brokenness of the U.S. public sphere, especially our media and fractured political system.

For nearly four years the press and half the electorate have been consumed with a vicious fantasy holding that the American president is secretly beholden to Russia. For all the damage it has done, this conspiracy theory nonetheless underscores the very real concern that voters share across the political spectrum—that they have little insight into the various instruments and mechanisms used to shape their lives, and that those choosing for them may not always be putting the security and prosperity of the U.S. public first.