Why Naftali Bennett Decapitated the Settler Right and What It Means for Israel’s Future

How the shaming of a soccer star led to the biggest shake-up in Israeli politics and finally unchained Netanyahu’s chief right-wing rival

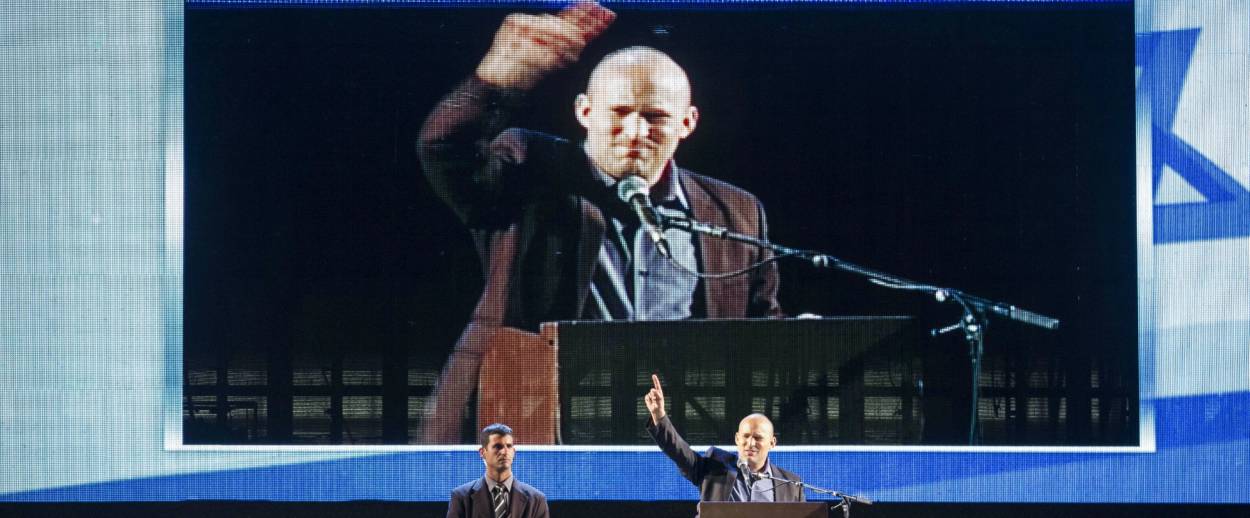

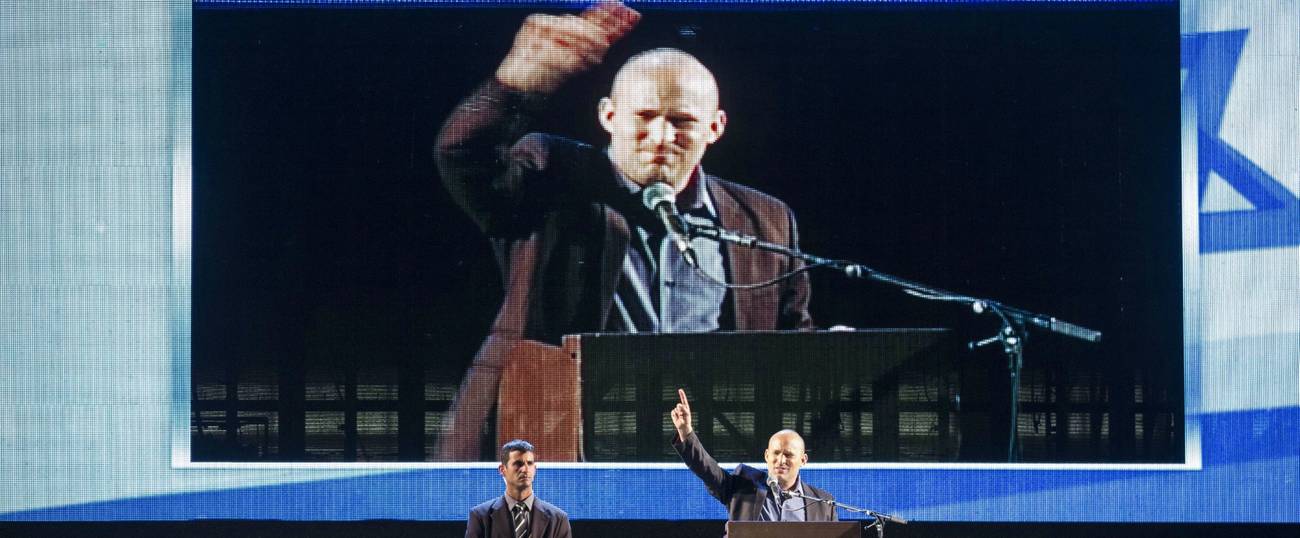

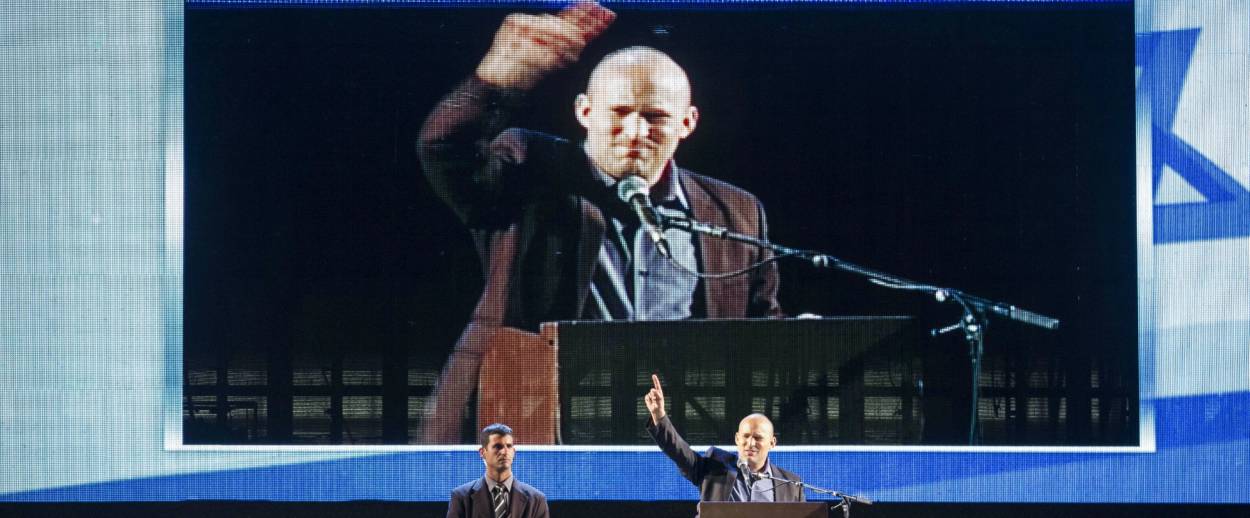

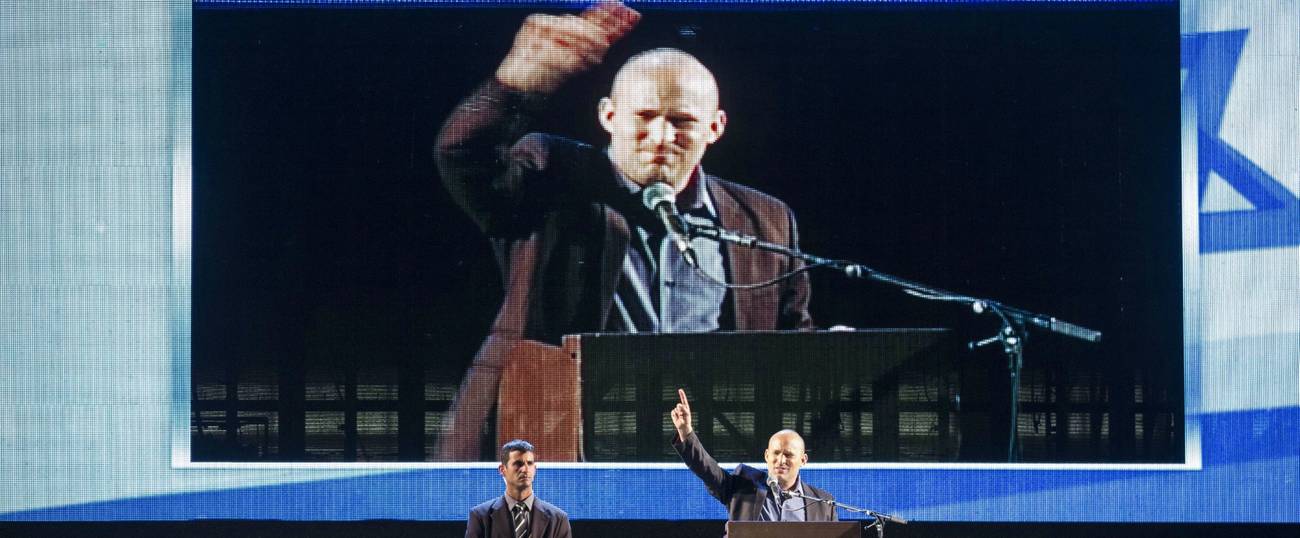

On Dec. 29, Naftali Bennett, the charismatic leader of Israel’s Jewish Home party—the vanguard of the country’s settler religious right—decided to blow it all up. At a press conference alongside Jewish Home’s No. 3 lawmaker, Ayelet Shaked, he announced that he was leaving to form a new party called “The New Right.” This move, which effectively decapitated the religious right on the eve of Israel’s elections, came as a shock to the political system, but it should not have. It was, on the contrary, inevitable.

Indeed, while Bennett announced his departure just last month, his exit had been written on the wall since Israel’s last election—specifically, since Jan. 29, 2015. It was on that day that it became clear that Bennett would never become prime minister as long as he was hamstrung by his party’s provincial base.

What happened on Jan. 29, 2015? On that day, Eli Ohana, one of Israel’s most decorated soccer stars, was forced to withdraw from Jewish Home’s electoral slate. The popular Ohana had been personally recruited by Bennett, who hoped to use his celebrity to telegraph a new face for the religious right: a political place not simply for religiously observant Ashkenazim, but also for Mizrahi Jews like Ohana who respected Jewish tradition but did not adhere to its religious laws. But despite a celebratory rollout of Ohana’s candidacy, the party faithful were not enthused. Top rabbis declared that they would not vote for Jewish Home while Ohana was on the parliamentary ticket. The soccer star and his family came under withering personal attacks. Ohana withdrew just three days after declaring his candidacy. When the dust settled, Bennett’s gambit to mainstream his party had backfired resoundingly, underscoring Jewish Home’s long-standing narrowness rather than showcasing a newfound broad-mindedness.

The Ohana incident essentially cemented the political ceiling on Bennett’s prime ministerial ambitions: so long as he was beholden to Jewish Home’s base, he would never achieve the necessary escape velocity from its most revanchist elements to succeed Benjamin Netanyahu. To do that, Bennett would have to leave Jewish Home behind.

The marriage between Bennett and the religious right had always been an uneasy one. The hip hi-tech entrepreneur was married to a non-Orthodox Jew, had no problem with LGBT people, and generally presented as more modern in his attitudes than many of the constituents he purported to represent. The settler right’s rabbis tolerated Bennett because he made a good frontman for their movement. As a yarmulke-wearing hi-tech millionaire who had served in Israel’s special forces, he was the embodiment of the religious Zionist dream. But while the party’s traditionalists turned to the untraditional Bennett in the hopes that he would win them votes, they did not always give him the latitude to do so.

At first, it looked like Bennett’s rebrand might just work. As soon as he assumed control of several religious parties in 2012, Bennett did everything he could to refashion them into an appealing mainstream political vehicle. He brought in Ayelet Shaked, a fellow former aide to Netanyahu who also happened to be completely secular, and made her the poster woman for his new, inclusive right-wing movement. Instead of arguing for settlements by citing scripture, Bennett began recasting them as a security necessity. Ceding the land that happened to be occupied by his constituents, he argued, would simply invite more terrorism, just as withdrawals from Gaza and Lebanon had led to the encroachment of Hamas and Hezbollah.

Outsiders were impressed by Bennett’s approach. New Yorker editor David Remnick devoted an entire 9,000-word piece on Israel’s 2013 election to the proposition that Bennett was poised to be its big winner. Israelis, however, were less convinced. Eretz Nehederet, the country’s SNL, caricatured Jewish Home’s leader as the robotic iBennett, a hip new politician produced in a lab who reliably spouted secular-sounding talking points but periodically malfunctioned and started ranting about blowing up the Temple Mount. When the election results came in, center-left journalist Yair Lapid’s Yesh Atid party—which did not appear in Remnick’s opus–had swept 20 seats, while Bennett’s new-look Jewish Home took only 12.

This was not a fluke. In fact, it would be Bennett’s high-water mark, as the same pattern repeated itself in the next election. In that cycle, Bennett personally appeared in entertaining political ads designed to appeal to the political mainstream, and enjoyed an early boost in the polls. Then his party publicly defenestrated Eli Ohana, and Jewish Home plummeted back to earth, dropping from 12 seats to 8 in the final election tally.

Officially, Bennett chalked up his loss to the fact that religious voters had flocked to back Netanyahu to ensure that Likud was the largest party in Knesset and able to form the next government. But in reality, the poor showing was also a product of Jewish Home’s unique liabilities as a political vehicle—a nominally right-wing party bootstrapped to an often-backward base that was distrustful of the religiously nonobservant, often openly racist, and constitutionally opposed to consensus Israeli policies like gay marriage. In the Knesset that followed, Bennett found himself forced to rebuke his own Knesset members for their naked anti-Arab bigotry, and compelled to stay in a teetering Netanyahu coalition that denied him the post of defense minister, largely because party leaders demanded he remain, effectively eroding his political leverage.

Once new elections were called for April 2019, Bennett had clearly had enough. Standing alongside Shaked, he jettisoned Jewish Home, essentially called its voters cheap dates in “Netanyahu’s pocket,” and pledged to build an inclusive right-wing party that would focus on bridging Israel’s religious-secular divide.

What this means in the short term is less clear than the long term. While “The New Right” has polled well in early surveys, it’s unclear how well it will perform once the campaign gets into full swing, and whether it will cause other smaller right-wing parties like Jewish Home to miss the electoral threshold and fall out of Knesset entirely.

In the long term, however, “The New Right” marks Bennett’s declaration of independence. No longer chained to the debilitating idiosyncrasies of the religious right, he and Shaked are now free to turn their considerable talents toward recruiting the mainstream right to their hard-right agenda: from open opposition to the two-state solution, to efforts to subordinate Israel’s judiciary to the Knesset, to more draconian responses to Palestinian violence. This agenda will no longer be hampered by the anchor of Jewish Home’s far-right stances on social issues or its parliamentarians’ embarrassingly explicit racist outbursts. This time, Bennett will finally be free to pitch his unique mix of liberalism and illiberalism to the Israeli electorate unfiltered.

And while he won’t be displacing Netanyahu in April, he might actually have a chance the next time around.

Yair Rosenberg is a senior writer at Tablet. Subscribe to his newsletter, listen to his music, and follow him on Twitter and Facebook.