Duo Benches Today’s Bentsher

A new egalitarian, LGBT-friendly version of the little post-meal book

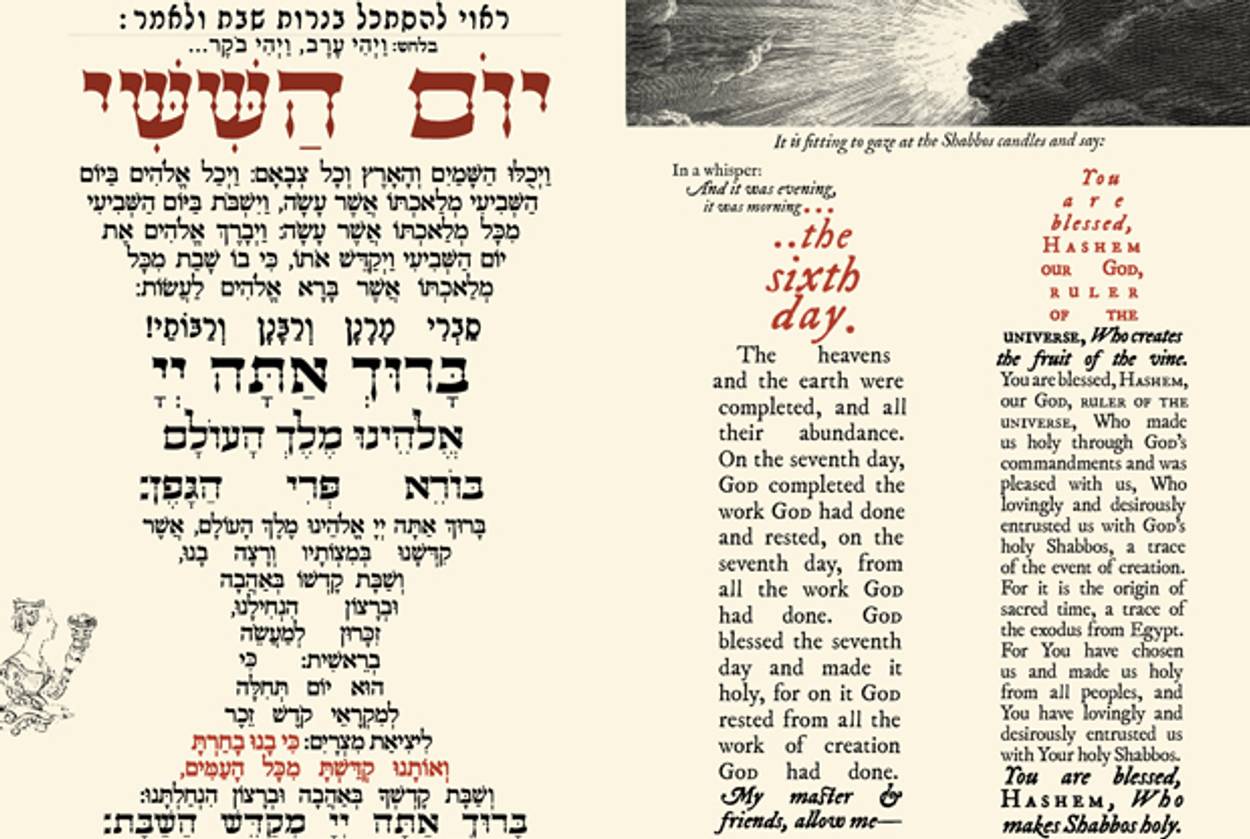

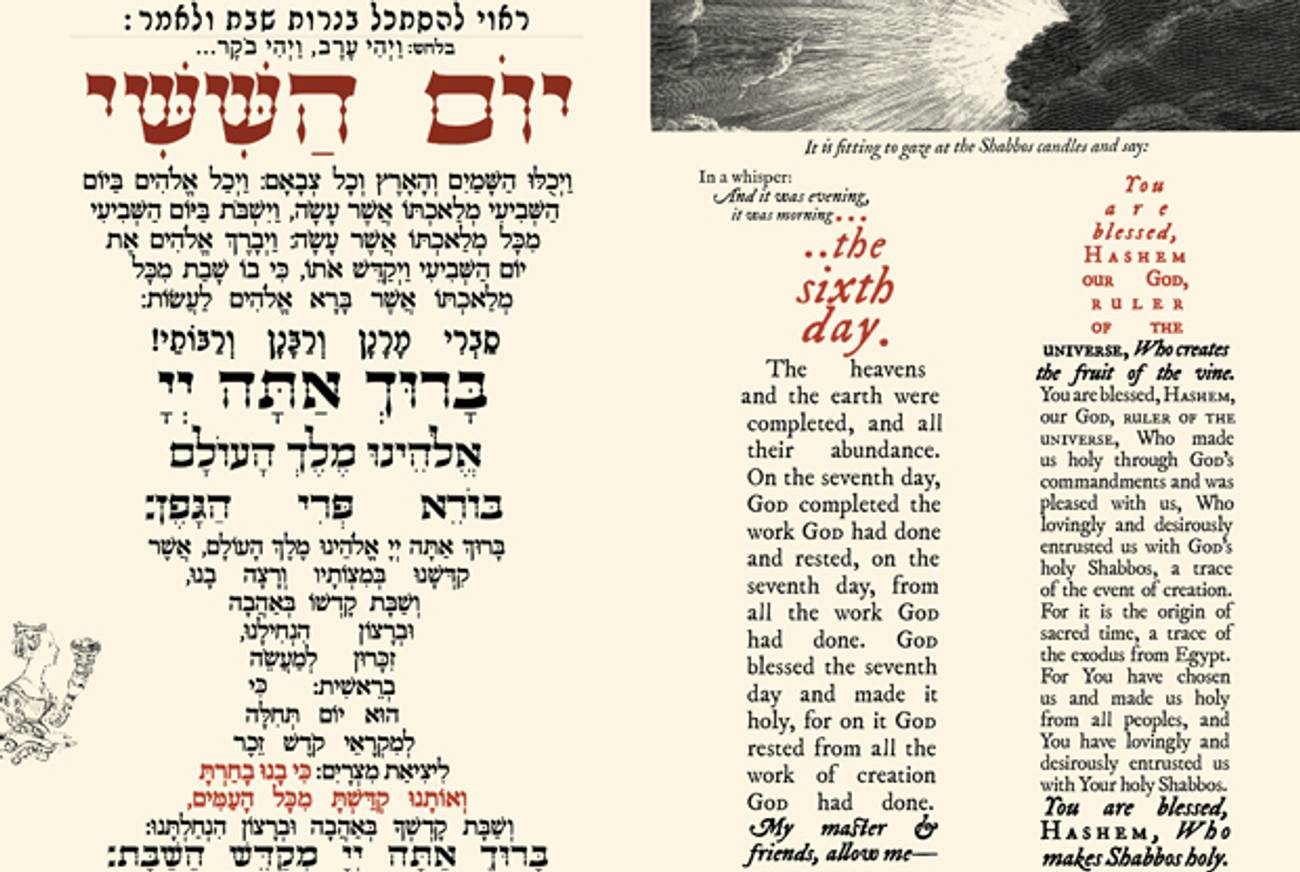

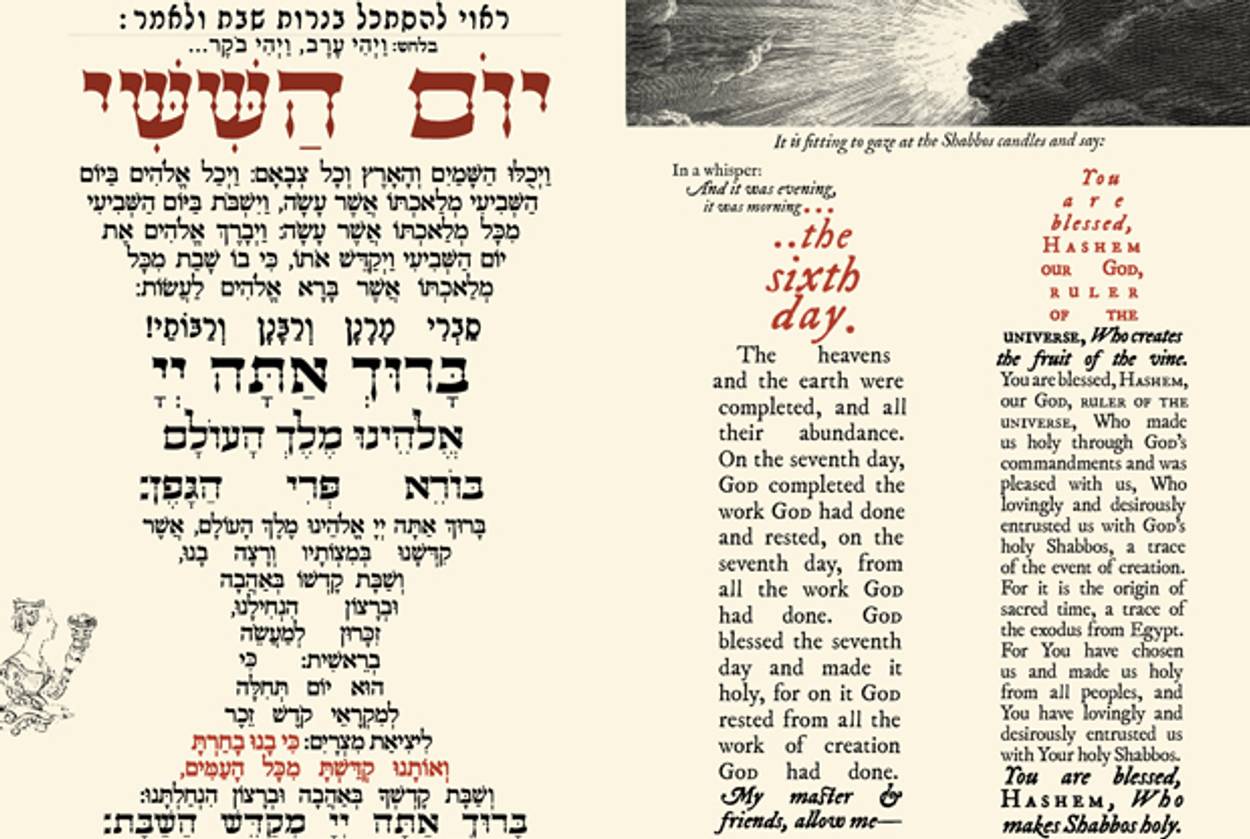

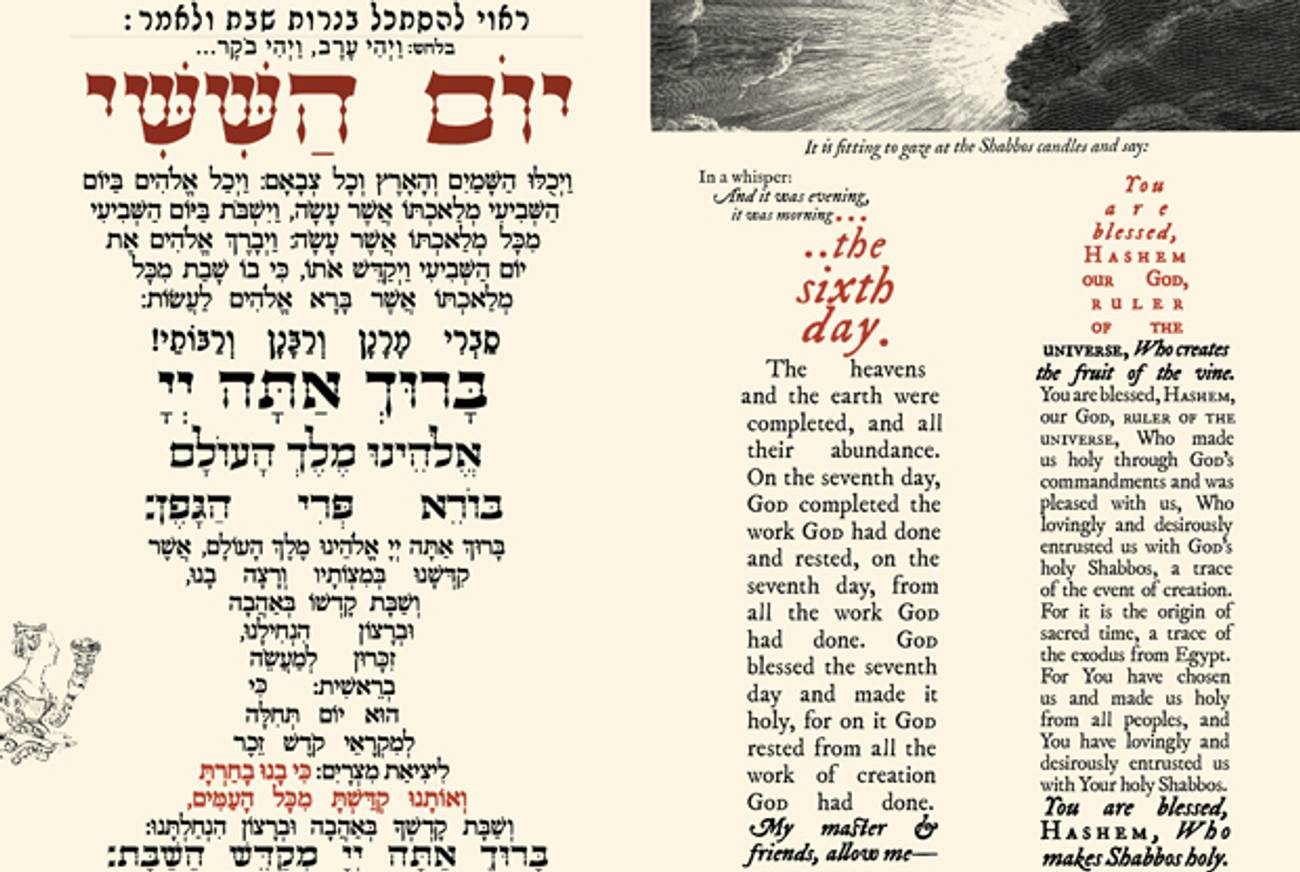

David Zvi Kalman and Joshua Schwartz are on a mission to restore a little booklet to its former glory. When bentshers, small scale pamphlets containing the Hebrew Grace After Meals, were first printed 500 years ago, they were large volumes lovingly adorned with woodcuts, engravings, and intricate drawings. Today, they have mostly been reduced to flimsy little things doled out as party favors at Jewish weddings.

“Jewish weddings are the worst thing to ever happen to bentshers!” according to Kalman. “Because bentshers are now mass-produced, there’s a push to make them smaller, and a push to make them cheaper. They’ve become much more utilitarian texts, and much less an object of beauty.”

At the end of October, Kalman and Schwartz—doctoral students at Penn and NYU, respectively—will release the second edition of Seder Oneg Shabbos, a visually arresting, meticulously designed bentsher that harks back to an earlier time in Jewish history. The book also contains a modern twist: “egalitarian and queer-inclusive language.”

The project was spearheaded by Schwartz, who had been mulling the idea of creating a beautiful, egalitarian bentsher for some time. The advent of Schwartz’s own wedding finally prompted him to take on the challenge. “It was a project that I was going to do with my then-fiancé,” he said. “We started talking about it online, and another couple was interested as well—a queer couple that were friends of ours—and that kind of helped it gain momentum. Then Kalman also indicated his desire and excitement to do something like this.”

Kalman and Schwartz made sure to tread carefully as they navigated the process of infusing a centuries-old text with modern sensibilities. They wanted to respect the tradition of the liturgy and preserve the integrity of the Hebrew—a language that is inherently gendered—while creating a product that would embrace both men and women, straight Jews and gay ones.

The duo ultimately decided to leave the Hebrew text intact, with a few exceptions. In the sheva brachot, the seven blessings that are bestowed upon a bride and groom, Kalman and Schwartz added additional options for blessing a groom and groom, a bride and a bride. (The booklet takes its name from this Yiddish word bentshn, “to bless.” Literally, it is a “blesser.”) They also shook up the standard translation of the bentsher text so that it would be, in their words, “gender balanced.” Kalman and Schwartz never refer to God as “He,” for example, relying instead on the neutral pronoun “Who.”

Other tweaks to the traditional text are more subtle. Next to Eshet Chayil (“A Woman of Valor”), an allegorical hymn that sings the praises of a virtuous wife, Kalman and Schwartz placed an illustration of a scene from the Book of Judith, in which Judith beheads the general Holofernes. They hope that the juxtaposition of these two female personas—one a wife, one a warrior—will prompt readers to consider a more nuanced portrait of womanhood than the hymn provides on its own.

The egalitarian, inclusive values that Seder Oneg Shabbos espouses are bound to rankle certain members of the religious community, but Kalman and Schwartz insist that they were not trying to make a political statement with their new book. Instead, they strove to produce a text that would align with the Judaism they live, that would feel right for their own Shabbat tables.

What distinguish this bentsher, ultimately, are less its progressive elements and more the degree to which it is rooted in the history of Jewish printmaking. Like bentshers of an earlier era, Seder Oneg Shabbos is large (six by nine inches), and rendered in soft creams and deep ambers. It is illustrated with images that were sourced from Jewish books of centuries past, and adorned with Hebrew typefaces that stretch deep into the annals of Jewish publishing. The goal, Kalman and Schwartz say, was to create a product that felt “haimish”—a Yiddish descriptor that can be loosely translated as homey, inviting, and familiar.

Kalman and Schwartz tackled the bentsher as their first project because when it comes to Judaism’s three central texts, the bentsher is something of an orphan child; unlike the Haggadah and the prayer book or siddur, the bentsher has not been invigorated by organizations like Koren and Artscroll.

“It was definitely a thrilling and tantalizing experience,” said Schwartz. But there is still work to be done. “I kept on hinting to David Tzvi, ‘OK, next we’re doing a siddur, right dude?’”

Related: Responsive Reading

Black Jewish Congregations Get Their Own Prayer Book, After Nearly a Century

Brigit Katz is an editorial intern at Tablet.