The Lost Poems of Ka-Tzetnik 135633

Auction house offering Auschwitz survivor’s elusive pre-war book for $7,000; copies also available at several libraries

The most significant moment at the Eichmann Trial occurred when the Polish-born writer Yehiel Feiner collapsed while testifying on the stand in Jerusalem, after he was asked a simple procedural question at the beginning of his testimony—the reason why he concealed his identify behind the pseudonym Ka-Tzetnik 135633 (Ka-Tzetnik is the Yiddish term for a concentration camp inmate).

He responded:

“It was not a pen name. I do not regard myself as a writer and a composer of literary material. This is a chronicle of the planet of Auschwitz. I was there for about two years. Time there was not like it is here on earth. Every fraction of a minute there passed on a different scale of time. And the inhabitants of this planet had no names, they had no parents nor did they have children. There they did not dress in the way we dress here; they were not born there and they did not give birth; they breathed according to different laws of nature; they did not live—nor did they die—according to the laws of this world. Their name was the number Ka-Tzetnik.”

Later in his testimony, Ka-Tzetnik stood and turned around, and he then collapsed on the ground.

Several years ago in Tablet, David Mikics explored the literary legacy of Yehiel Feiner, with a particular focus on his post-Holocaust works of Salamandra (1946) and House of Dolls (1953), written under his name of Ka-Tzetnik 135633, and noted, almost in passing, a small book of Yiddish poetry that he published in 1931. Before the Holocaust, Feiner was a musician, writer, and poet, who contributed articles to local Yiddish newspapers and, in 1931, published a volume of twenty-two Yiddish poems. However, as historian Tom Segev writes in The Seventh Million, “[a]fter Auschwitz, [he] made every effort to consign his early work to oblivion, going so far as to personally remove it from libraries. He also discarded his original name. Auschwitz, having robbed him of his family, also robbed him of his identity, leaving only the prisoner.”

In his Tablet article, Mikics recounted the story about how, in 1993, when Ka-Tzetnik was told that a copy of his 1931 collection of twenty-two poems was available at Hebrew University’s National Library of Israel, “he stole it, burned it, and sent the charred remains back to the library with the instruction that the rest of it should be reduced to ashes, like all of his pre-Auschwitz existence.” His request to the director of the library’s circulation department was, “to burn the remains of his book just as my world and all that was dear to me was burnt in the Auschwitz crematorium.” For the past few decades, whenever scholars analyzed the literary writings of Ka-Tzetnik, they have focused on Salamandra and House of Dolls, owing to the fact his 1931 volume was removed from circulation by the author himself.

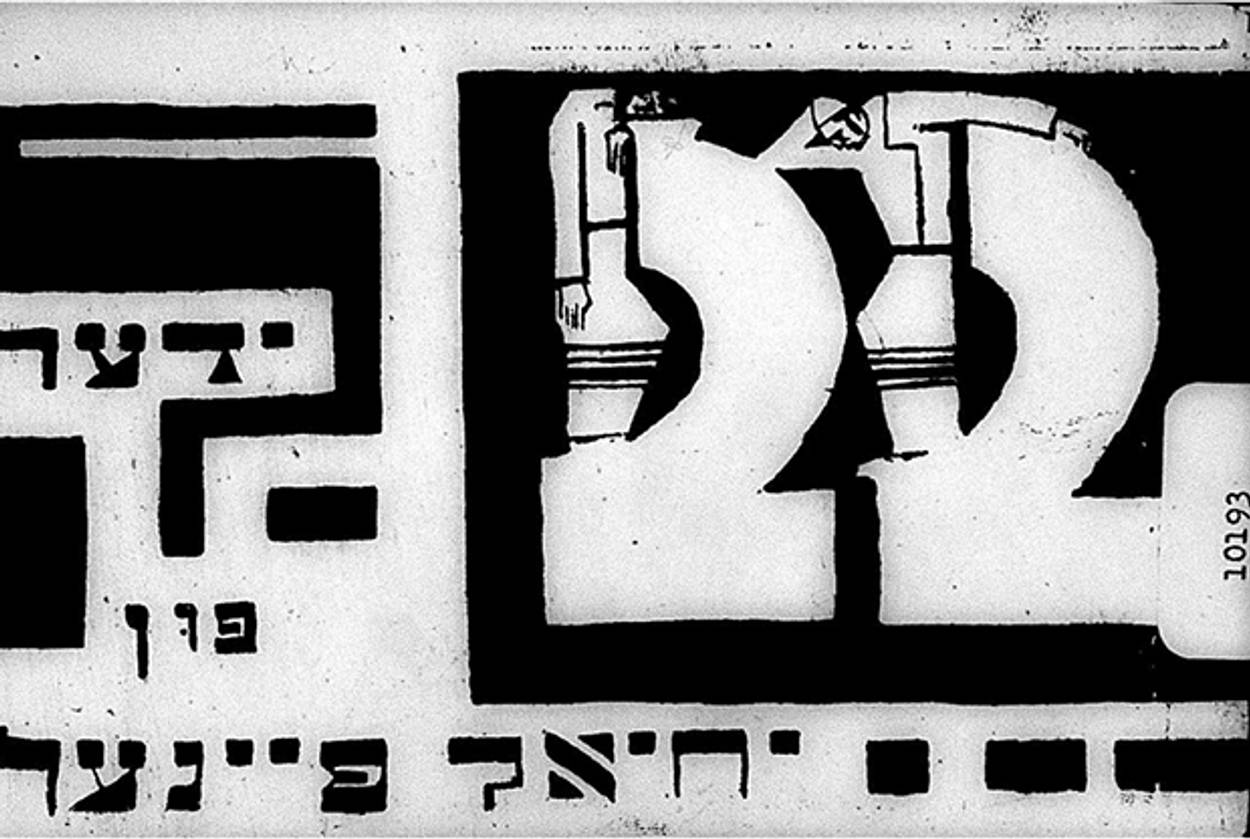

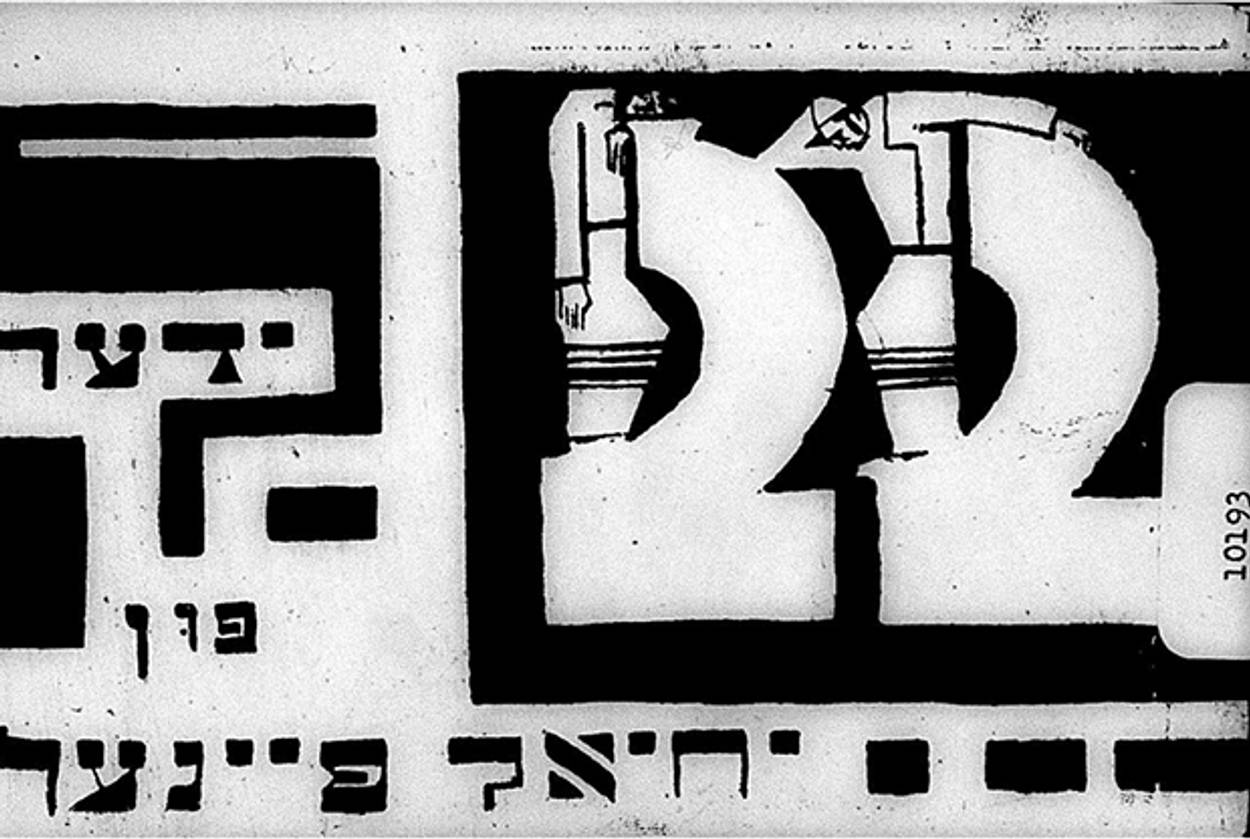

But in what is being presented as a major find, the Kestenbaum & Company auction house in New York City recently announced that Lot 119 of their June 26 auction was an autographed first edition, with photographic frontispiece, of Yehiel Feiner’s 1931 Tsveyuntsvantsik—“Twenty-Two Poems”—which they describe as “possibly the only complete copy extant of … Ka-Tzetnik’s immensely scarce first book written in his youth in Poland, of the utmost rarity.” The sale price for Thursday afternoon is estimated at $7,000-$10,000.

Upon seeing the auction listing, I reached out to Professor Yehiel Szeintuch, who informed me through a colleague that though Ka-Tzetnik famously destroyed a copy of Twenty-Two Poems from the National Library of Israel, Szeintuch has since replaced the copy from his own collection. Seeking to further establish the rarity of the volume at auction, I also walked into The YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in Manhattan and, after some research into Ka-Tzetnik’s various publications that are available in their great Yiddish archive, a copy of his work was located within The Vilna Collection, the surviving remnant of YIVO’s prewar library from Vilna.

Over the past week, in my efforts to learn more about Ka-Tzetnik’s Twenty-Two Poems, I asked my friend Professor Naomi Seidman, a scholar of Yiddish literature at Berkeley’s Graduate Theological Union, to explore some of the themes of Ka-Tzetnik’s earliest published work with that of his post-Holocaust writings. In a common trope of Yiddish poetry, Seidman found that Twenty-Two Poems reflected Feiner’s “attachment to traditional Jewish language as a metaphor for modern artistic creation,” and that “everything the young poet meets falls into the ready-made sighs and shadowed gravestones and bitter heart of the young poet.”

She also wrote, “One potentially interesting question is what happens when such a poetic sensibility (abstract, death-obsessed, full of cliches about poetry and art), meets the concrete details of the Holocaust? Everything the young poet meets falls into the ready-made sighs and shadowed gravestones and bitter heart of the young poet. So what, then, when he meets what we know he meets?”

I reached out to Kestenbaum & Company and asked whether they are aware that copies of Ka-Tzetnik’s Twenty-Two Poems are currently available to be studied at the National Library of Israel and at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York, among other research institutions, and if this detail will be made known at the auction on Thursday afternoon.

A Kestenbaum representative responded that “the copy contains the exceptionally rare frontispiece photographic portrait of the author,” and that they will not announce that there are, as well, several academic libraries that also have copies of Ka-Tzetnik’s Twenty-Two Poems available to researchers.

Related: Holocaust Pulp Fiction

Menachem Butler, an associate editor at Tablet Magazine, is the program fellow for Jewish Law Projects at the Julis-Rabinowitz Program on Jewish and Israeli Law at the Harvard Law School, and a co-editor at the Seforim blog. Follow him on Twitter @MyShtender.