Did Sandy Koufax Lay Tefillin During the 1965 World Series?

Unraveling Jewish baseball’s urban legend about the southpaw and the Rebbe

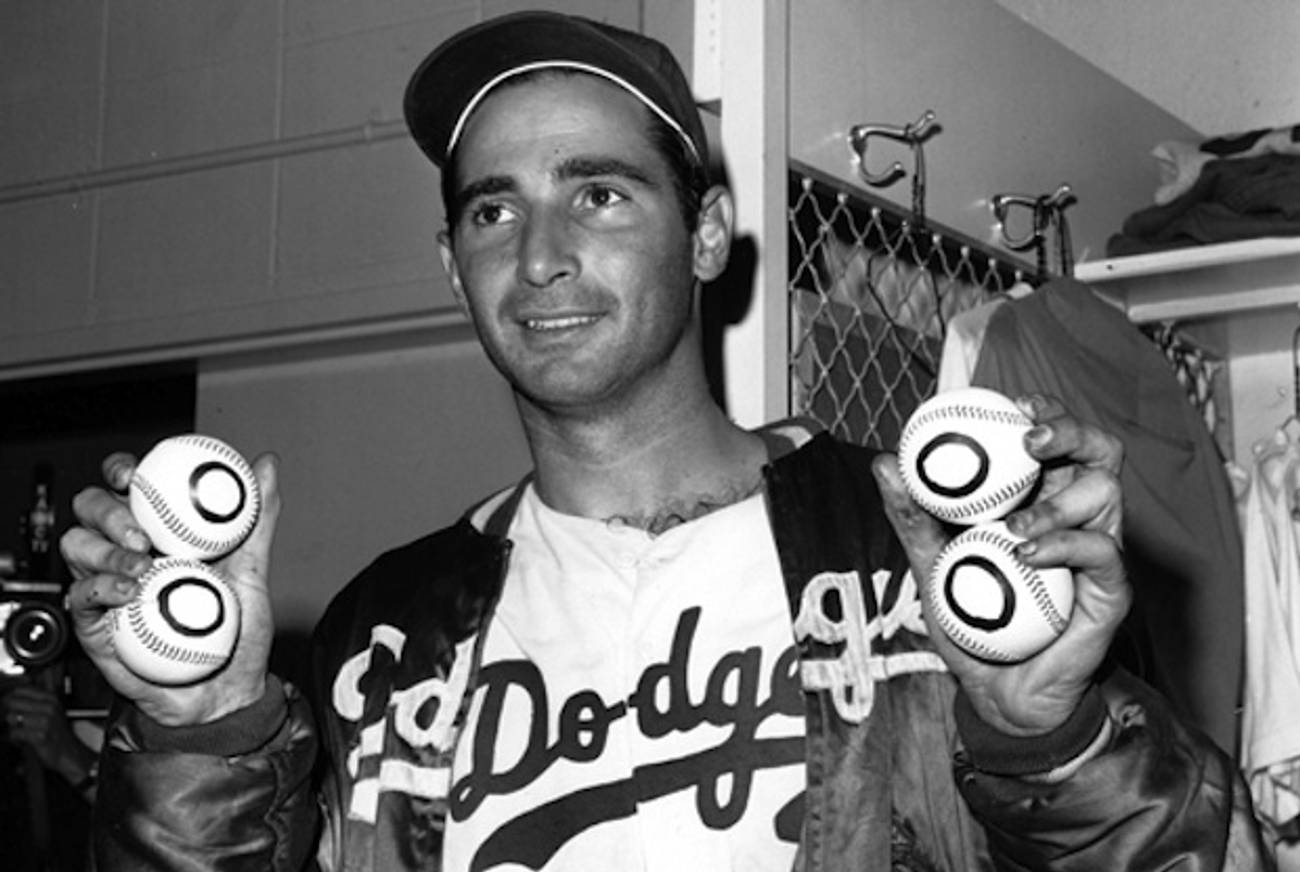

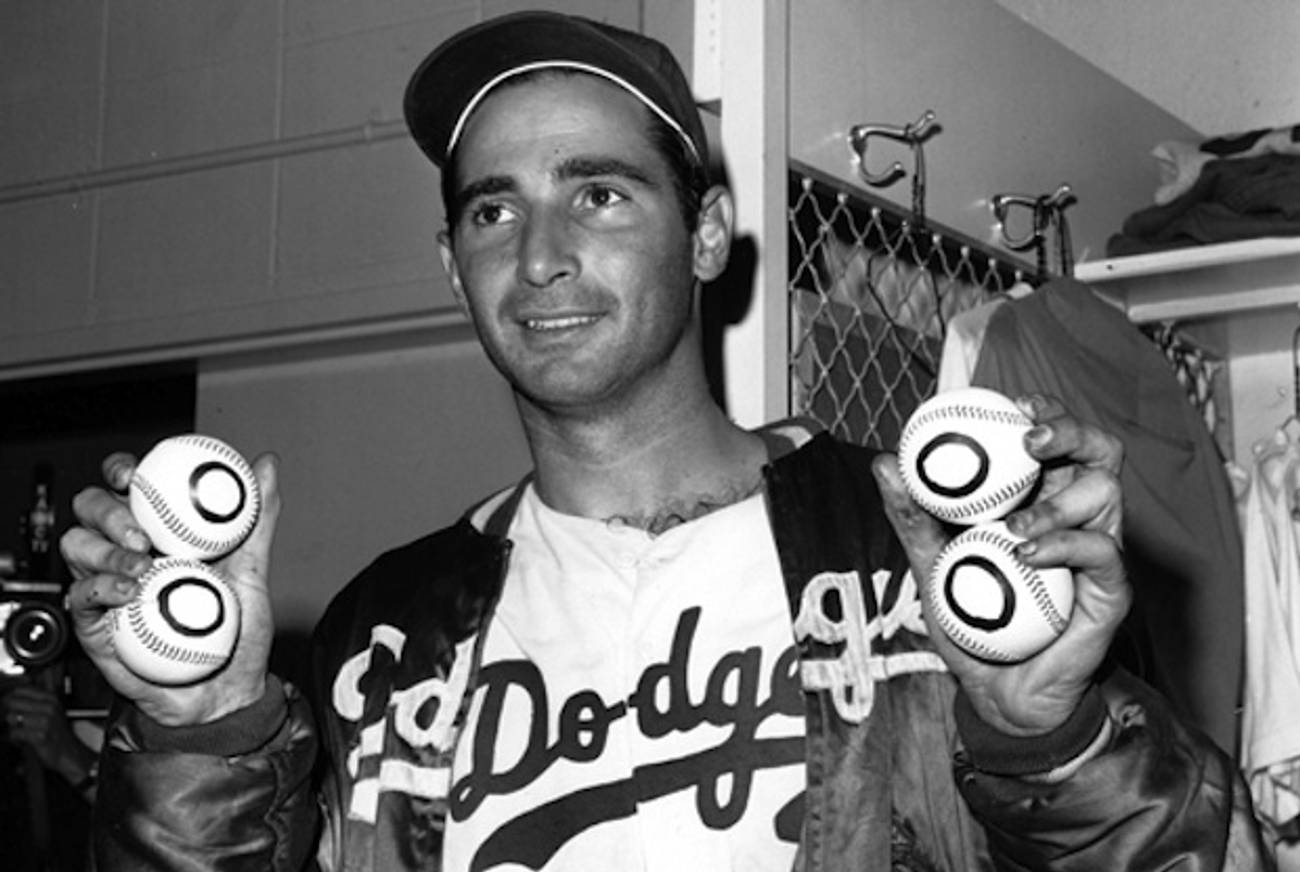

While sports fans barely agree on anything, it is almost universally accepted that there have only been two truly great Jewish stars in Major League Baseball: Hall of Famers Hank Greenberg and Sandy Koufax. Greenberg was one of baseball’s greatest sluggers who played primarily for the Detroit Tigers in the 1930’s and 40’s, and Koufax, who played for the Dodgers (in Brooklyn and then Los Angeles) from 1955 through 1966. Koufax was arguably the greatest left-handed pitcher of all time.

While neither Greenberg nor Koufax was known to be particularly observant, both made historic decisions that have had tremendous religious and cultural significance for generations of American Jews. During the middle of a pennant race in 1934, Greenberg famously sat out of a game that fell on Yom Kippur. Then, 31 years later, Koufax missed his slated spot in Game 1 of the 1965 World Series versus the Minnesota Twins because it conflicted with Yom Kippur.

While much ink has been spilled on the events that took place on those famous holy days, There’s a lesser-known story of what happened to Koufax on the day after Yom Kippur, when a devoted baseball fan and disciple of the Lubavitcher Rebbe connected with the southpaw. The story has become something of an urban legend in certain baseball-obsessed Jewish circles.

On Yom Kippur, October 6, 1965, despite having future Hall-of-Famer Don Drysdale on the mound as their starting pitcher, the Dodgers lost Game 1 of the World Series against the Minnesota Twins. The brash Drysdale, known as much for his fun-loving personality as his threatening fastball, reportedly said “I bet you wish I was Jewish too” when manager Walter Alston decided to yank him from the game. Koufax was notably absent from the ballpark that day out of respect for his religion. Koufax thus continued his practice of not pitching on the highest holy day—only this was the first time that his decision had such major ramifications.

While the rabbi of the Temple of Aaron Synagogue in St. Paul, Minnesota always maintained that he saw Koufax in shul on that Yom Kippur, Jane Leavy’s noted biography of Koufax quotes friends who maintain that he spent the day in his hotel room. Be that as it may, little did Koufax know that he would be in for quite an interesting visit in that same hotel room the next day. After missing Game 1, Koufax was, of course, the scheduled pitcher for Game 2 on October 7. That morning, a young Lubavitch rabbi, the proud bearer of a famous baseball surname, Moshe Feller, made his way over to the Saint Paul Hotel with a special delivery for Koufax in appreciation of his respectful stand: a pair of tefillin.

I recently called Feller to discuss the events of that day. He graciously retold the story from nearly 50 years ago in impressive detail. Feller was born and raised in Minneapolis, and despite growing up in a non-Hasidic household and attending the non-Lubavitch Yeshiva Torah Vodaath in Brooklyn, N.Y., he became a student of the Lubavitcher Rebbe. In the early 1960s, the Rebbe sent Feller back to his hometown and appointed him as the regional director of the Merkos L’Inyonei Chinuch, the educational arm of the Lubavitch movement, a position that Feller holds to this day.

Feller knew that the Rebbe always wanted to associate famous people with the performance of positive Jewish commandments, and what better way of accomplishing this goal than recognizing the golden left arm of Sandy Koufax? Feller arrived at the hotel’s front desk and briskly said, “I am Rabbi Feller and I want to see Mr. Koufax.” The clerks all knew that Koufax had sat out the previous day’s game because he was Jewish and likely figured that Feller was Koufax’s rabbi. They decided to let Koufax decide whether Feller should be allowed to go up to the room. They gave Feller the phone number. When Koufax picked up, Feller said that he represented the Lubavitcher Rebbe. He told Koufax that the Rebbe was very pleased with Koufax’s decision not to pitch the day before because countless Jews had decided not to work or attend school on Yom Kippur after learning that Koufax would not pitch. Feller then said that he would like to give Koufax a pair of tefillin. Koufax invited Feller up to his room and respectfully accepted the gift.

Interestingly, because tefillin are worn on a person’s weaker arm (a righty wears them on his left, and a lefty on his right) Feller had specially prepared the tefillin to be worn on Koufax’s right arm. Feller wanted to help place the tefillin on that arm, but Koufax declined, saying that he knew how to do it.

Feller immediately penned a letter to the Lubavitcher Rebbe describing the meeting. Less than two weeks later, on the night of Simchat Torah, the Rebbe described to his adherent Hasidim the events of the meeting between Koufax and Feller, although he referred to Koufax as “the pitcher” and Feller as the “avrech,” or young rabbi. The Rebbe concluded the story by noting that Feller departed from Koufax leaving the tefillin on the table. The Rebbe went on to say that ultimately Koufax will merit to put the tefillin on, and so it shall be that another Jew performs the holy ritual of wearing tefillin.

When I asked Feller if he believes that Koufax ever put the tefillin on, he noted that Koufax lost his start on the day he did not put the tefillin on in Feller’s presence. He did, however, return to win Game 5 by a shutout—as he did seventh and deciding game, on only two days’ rest. Interestingly, the published version of the Rebbe’s Simchat Torah talk contains a humorous footnote suggesting that perhaps Koufax lost the second game because he hadn’t donned the tefillin.

After speaking with Feller, I was determined to find out what really happened, and to attempt to approach Koufax himself for the answer. I turned to Larry Ruttman, the author of American Jews & America’s Game. Ruttman graciously agreed to forward a letter from me to Koufax requesting information regarding his meeting with Feller and the fate of the tefillin. Had Koufax ever worn them? Does he still have them?

After signing my name on the letter, I left my home address and my cell phone number. I also attached an article from the Jewish newspaper for the Twin Cities, the American Jewish World, from November 19, 1965, one of the earliest published accounts of the meeting between Koufax and Feller. Each day after that I would rush home after work to open up the mail, hoping that Koufax would send me a response.

I was unprepared, to say the least, when my phone rang the following week with a Vero Beach number flashing on the caller ID. Calming down, I answered the call, immediately recognizing Koufax’s deep voice as he asked to speak with “Aaron.”

“This is Aaron,” I said. “Is this Mr. Koufax?” He confirmed that he indeed was on the line and acknowledged receiving my letter, but he then said he was afraid he couldn’t help me with my article. I figured that this might be the case. After all, Koufax has been avoiding interviews and queries for some 50-plus years.

I did tell Koufax how I have always idolized him as a player and a man, especially as a Jewish Los Angeleno who avidly follows the Dodgers. Koufax told me that he appreciated my kind words. I then reflexively gave Koufax a blessing. I said: “God should grant you many more years of health and happiness,” a blessing that he warmly received. “The same to you,” he said. And with that, our short conversation was over. Never has a rejection brought me such happiness.

Previous: ‘Mantle, Shmantle—Long as We Got Abrams’

Related: Forget Peanuts and Cracker Jack. What Jews Love About Baseball Is Jewish Players.

Aaron R. Katz is an associate in the corporate and securities practice at Greenberg Traurig. He lives with his wife and three children in Israel.