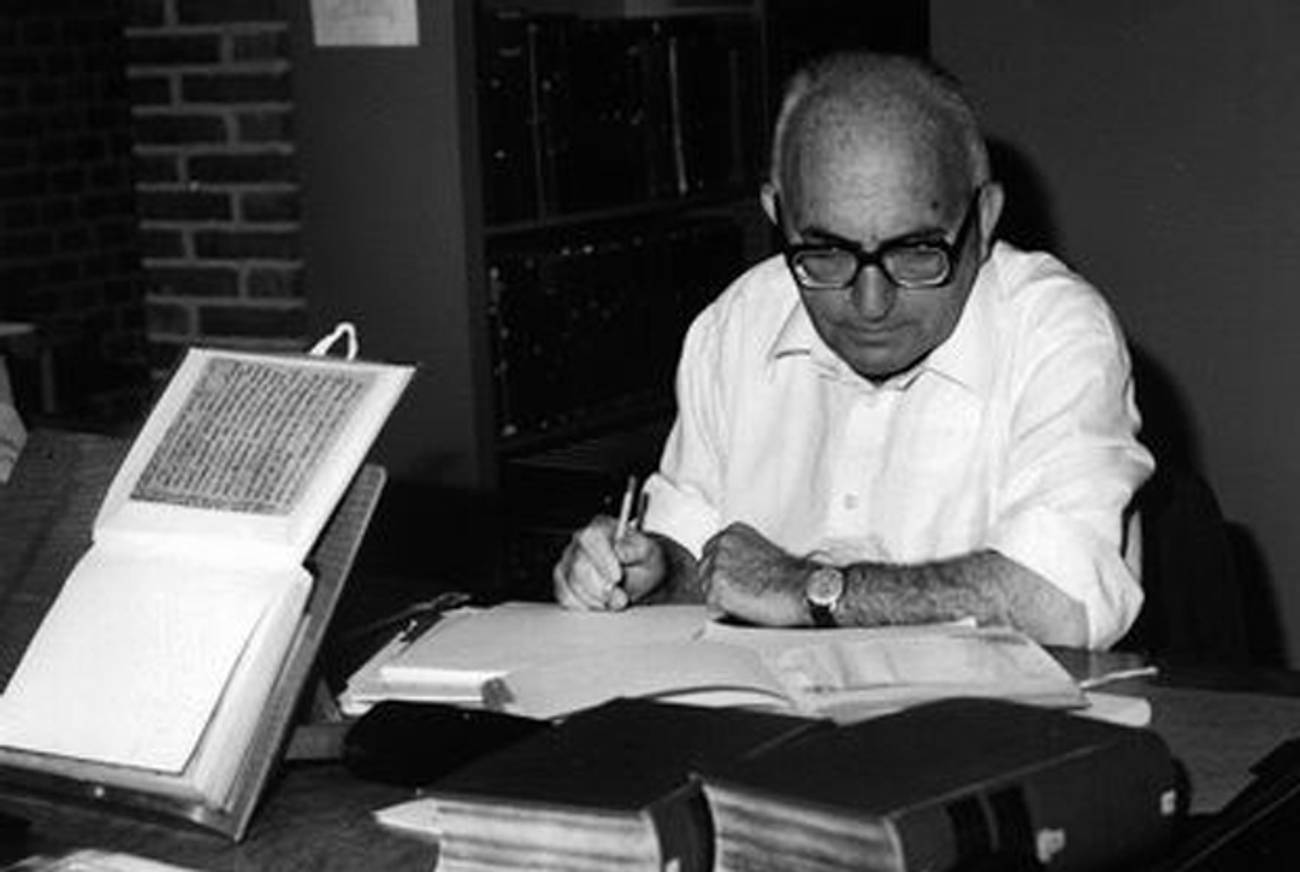

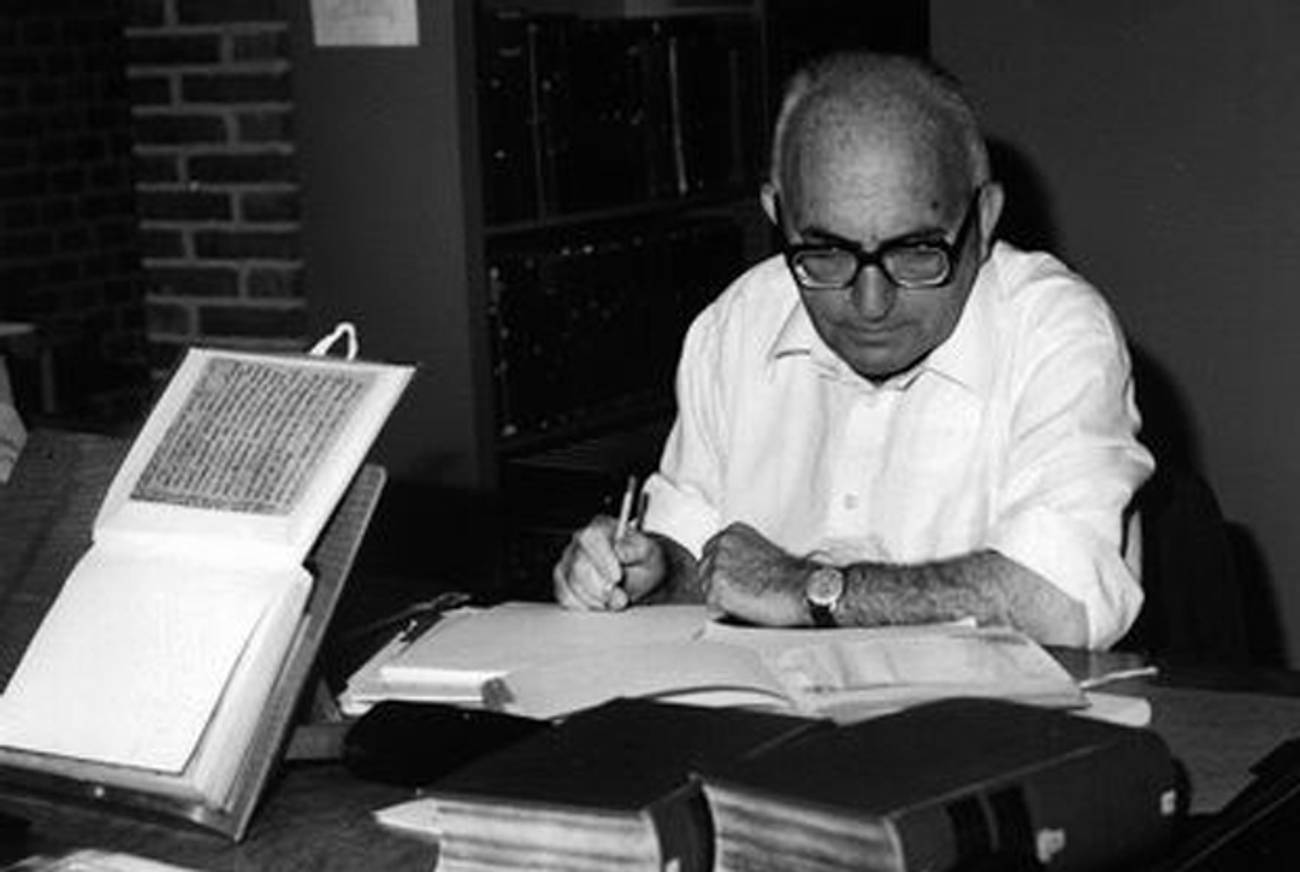

Remembering Moshe Gil, Historian of Medieval Jewry

A friend and former classmate pays tribute to the late scholar and author

Moshe Gil, who died in January at 92, was born in Bialystok, Poland in 1921 and raised in Romania. He moved to Palestine in 1945 and was a kibbutznik, later becoming a professor at Tel Aviv University and a prolific historian of medieval Jewry in the Islamic world. What follows is a personal recollection by Gil’s former classmate, friend, and colleague, Noam Stillman.

Although there were a number of older (today politely called “non-traditional”) students in our graduate program in Oriental Studies at the University of Pennsylvania in 1968, Moshe Gil certainly was—or seemed to be—the oldest. He was old enough to be my father. But with his easygoing manner and wry sense of humor, he quickly became a friend. He had come to Penn to work with the doyen of Geniza studies, Shelomo Dov Goitein, and already had his research topic mapped out.

His devoted wife Shoshana, whom everyone called by her nickname Mausie, took care of the apartment and their three daughters with military efficiency, making sure that he was not disturbed when working. He finished his coursework and dissertation in just two years, and we marched side by side at commencement in 1970. The 600-page book that grew out of his dissertation was published six years later and titled, Documents of the Jewish Pious Foundations from the Cairo Geniza. Many such weighty works were to follow in the decades to come.

Gil had a remarkable talent for learning languages. Although he had never taken first-year Persian, he started in our intermediate class after teaching himself the elementary grammar. He said that at his age, he didn’t have time to waste a year getting the basics. Since I had a good grounding in Latin, he liked to quiz me from time to time, though his was even better. I don’t know how many languages he knew—Hebrew, Yiddish, Romanian, Aramaic, French, German, Latin, Greek, English, and Russian too, I think—but he spoke them all with a thick accent. He was amused that our teachers put such a heavy emphasis on precise pronunciation since, as he said, “What difference does it make? If I say the ship was grazing in the field, you know full well that I am not talking about a boat!”

When I asked him once how he knew one particular Slavic language, he told me quite casually that when he was in prison, a fellow inmate taught him. At the time, I was so startled that I didn’t ask for details, although I later learned that he had been sentenced to 25 years in prison in Romania in 1942 for his underground activity as a leader of the Hashomer Hatzair Zionist underground. He was released when the war ended, and immigrated to Palestine in 1945, becoming a founding member of Kibbutz Reshafim in the Bet Shean Valley. He worked as a raftan, a dairyman, but as he a recounted in an interview published years later, he read everything he could get his hands on.

His academic career didn’t begin until 1965, when the Kibbutz Artzi movement sent some talented members to Tel-Aviv University for a one-year enrichment program to train them as teachers. It was there that he became enamored with the study of history and languages. Although he had never before attended university, he completed the coursework and thesis for a Master’s degree on the struggle over land in Roman Palestine based on Greek papyri, Latin legal literature, the Jerusalem Talmud, and other rabbinic sources.

When he learned that Tel Aviv University was interested in developing courses on Jews under Islamic rule, he turned his talents in that direction, and, as he said in the interview, “between one milking and another” he became interested in Hiwi ha-Balkhi, a Jewish freethinking heretic in 9th-century Iran. That same year he published a little Hebrew book, Hiwi ha-Balkhi the Khorosani Atheist. Gil later referred to the book as “popular, not written according to academic rules”—although it should be noted that it had footnotes from Hebrew and Arabic primary sources and works of English, French, and German scholarship. Everything, of course, is relative, and compared with his weighty multi-volume works based upon many hundreds of documents, this early book must have seemed to him like light stuff.

During his years on the faculty of the Chaim Rosenberg School of Jewish Studies at Tel Aviv University, where he eventually held the Joseph and Ceil Mazer Chair in the History of the Jews in Muslim Lands, Gil published two monumental historical studies: Palestine During the First Muslim Period (634-1099), and In the Kingdom of Ishmael. Both works consisted of a single volume of historical synthesis followed by Geniza documents (619 in the former work and 846 in the latter), mostly in Judeo-Arabic, with translations and notes. The first historical volume of each appeared in English as A History of Palestine, 634-1099 and Jews in Islamic Countries in the Middle Ages. It was through these translations that he became known to the non Hebrew-speaking scholarly world.

In 1998, Gil was awarded the Israel Prize, the nation’s highest honor, for his contributions to Israeli scholarship. He was, however, not without his critics, particularly among the medievalists at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, some of whom took serious issue with some of Gil’s readings and interpretations of Geniza manuscripts. Gil also challenged some widely held views on the early history of the Judeo-Islamic encounter, both in Arabia at the time of Mohammad and during the Muslim conquests of the Near East, and this too engendered spirited opposition. But he also, deservedly, had his admirers and supporters and trained a small, devoted cadre of scholars who follow in his footsteps.

Norman A. Stillman is the Schusterman/Josey Professor of Judaic History at the University of Oklahoma and Director of the Program for Judaic & Israel Studies. His books include The Jews of Arab Lands: a History and Source Book and The Jews of Arab Lands in Modern Times. He is the executive editor of the award-winning five-volume Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World.

Norman (Noam) A. Stillman is the Schusterman/Josey Professor of Judaic History at the University of Oklahoma and Director of the Program for Judaic & Israel Studies. His books include The Jews of Arab Lands: a History and Source Book and The Jews of Arab Lands in Modern Times. He is the executive editor of the award-winning five-volume Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World.