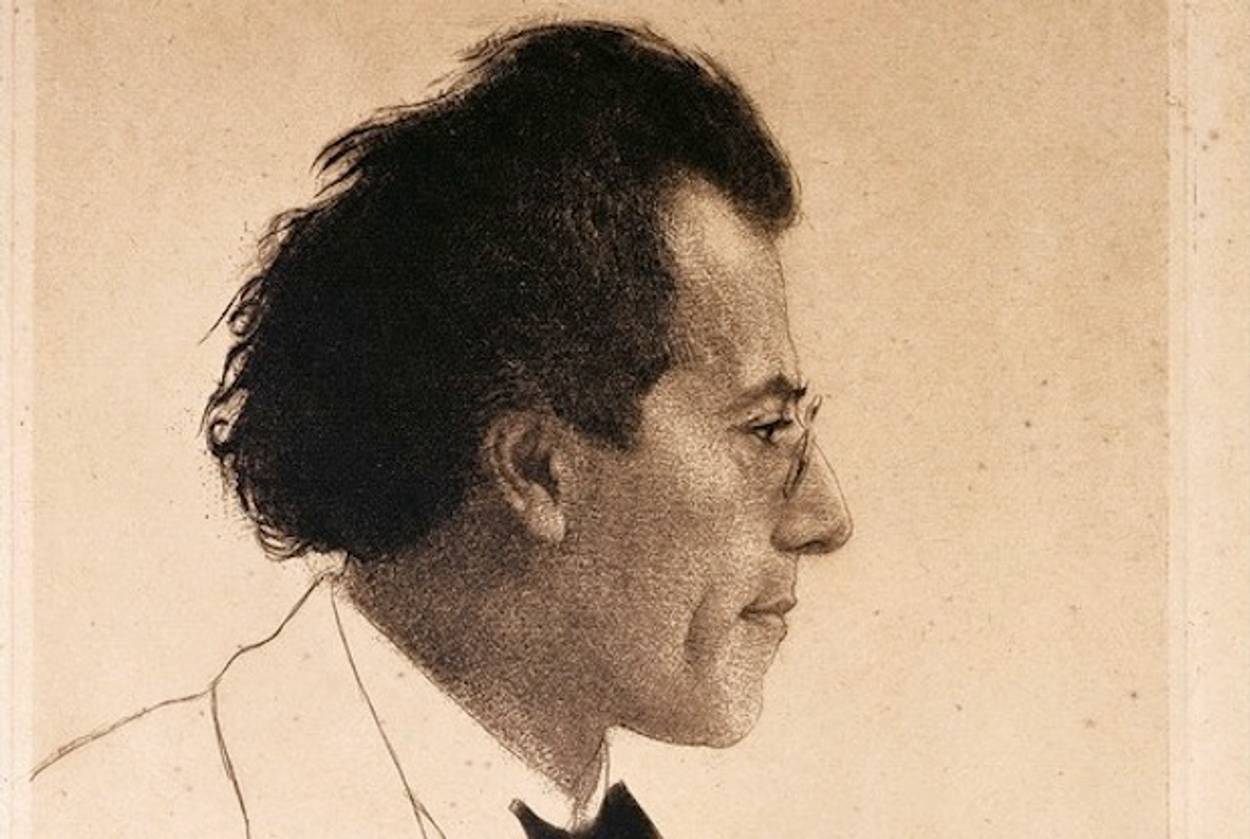

The Missing Gustav Mahler Picture

A story about intrigue, music, lineage, and tradition

As Leonard Bernstein closed his storied run at the helm of the New York Philharmonic in 1969, he chose Gustav Mahler’s Third Symphony for his final performance. Bernstein had long championed Mahler’s music, bringing about a revival of interest in the United States. The Third is a difficult symphony, one that was chaotically inspired in part by Schopenhauer’s concept of the universe willing itself into being. Its first movement often lasts over 30 minutes, an extraordinarily long opening salvo.

The Third is notable for a lot of things. The use of trumpets to produce a heroic feel. The controversial incorporation of a marching band sound in certain parts. In the middle of the third movement, Mahler writes in a solo part for a posthorn–the instrument once used to announce the arrival of the mail–a flourish that was said to remind Mahler of his youth when the posthorn would sound and bring news of the outside world to his small Bohemian village.

In many interpretations of the Third, in accordance with Mahler’s instructions which are scribbled in the notes, the posthorn solo is performed away from the rest of the symphony, sometimes above in the rafters, like the distant call of the divine. Here’s one version of the solo:

The trick is a tribute that evokes nostalgia. Appropriately, when Alan Gilbert–a serious Leonard Bernstein devotee–took over the New York Philharmonic a few years ago, he chose Mahler’s Third as the first major performance of his tenure. Mahler links Gilbert to Bernstein, but since Mahler also helmed the New York Philharmonic just prior to his death in 1911, Mahler links a city to an entire century. (It also seems worthwhile to note that Mahler, while born Jewish, was forced to convert to Roman Catholicism to secure his post in Vienna, his last stop before New York.)

Today, the New York Times had a fascinating story about Arnold Schoenberg, the composer and painter, who had an interesting and difficult relationship with Gustav Mahler.

Twenty-five years ago, when the daughter of Arnold Schoenberg was working through his archive for a book project, she came across an empty picture frame. It was missing what the Schoenberg family calls one of the composer’s most precious possessions: a signed picture of Gustav Mahler with a musical quotation from Mahler’s Symphony No. 2.

(Alas, I did not have any cool stories or insights about Mahler’s Second.)

The picture was reportedly found recently by Cliff Fraser, a Los Angeles man, who is trying to sell it back to the Schoenberg family for $350,000. How Mr. Fraser came into possession of the picture is being disputed as is whether or not he has the right to sell it at all. More important than the dispute itself, which would make for a great screenplay, is the history behind the heirloom, which was given by Mahler to Schoenberg over a century ago, but remains just as valuable today.

While the mystery is perplexing, it is also a reminder of one of the more remarkable relationships in music history: between the older master, Mahler, who pushed the concept of the 19th-century symphony to its limits, and the young modernist, Schoenberg, whose conception of harmony changed the sound of classical music.

For more, be sure to check out our Vox Tablet podcast with Alex Ross, who talks about Arnold Schoenberg in the context of his fantastic book, The Rest Is Noise.

Related: From Decadence to Minimalism [Tablet]

Clues to Whereabouts of Schoenberg’s Missing Mahler Picture [NYT]

Adam Chandler was previously a staff writer at Tablet. His work has appeared in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Atlantic, Slate, Esquire, New York, and elsewhere. He tweets @allmychandler.